Language Maintenance and Language Shift of the Maltese Migrants in Canada L Ydia Sciriha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 367 April 2021

[Type here] MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 367 April 2021 1 [Type here] MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 367 April 2021 Easter in Malta Atmosphere Easter is a chance to dive into the culture of the Maltese islands and experience something very special. Eat, drink, dance and celebrate, join the street processions and enjoy the friendly jubilant Easter atmosphere. Malta loves to celebrate and generally does it in a colourful and joyous fashion. Holy Week Easter in Malta and Gozo is not just a weekend event, it is a celebrated for whole week leading and building up to Easter weekend. Starting on the Friday prior to Good Friday, the Statue of Our Lady of Sorrows is carried in a procession through the streets of Valletta and many other small towns and villages. This starts off the celebrations for the Easter week. Maundy Thursday Maundy Thursday – the eve of Good Friday. This is when the ‘seven visits’ takes place, traditionally people visit seven different alters in seven different churches to pay homage to the Alter’s of Repose. Good Friday Good Friday is a day of mourning and can be a sombre day. Churches take down the ornamental decorations and no bells are rung and then procession run through the streets of all towns and villages. Malta does have some special and spectacular processions particularly Zebbug which is renowned for its extravagance, use of horses and involves hundreds of cast members making this a big tourist attraction. In Gozo the most notable procession can be seen in Xaghra. Easter Sunday While Saturday remains a slightly sombre moment, Easter Sunday is a real celebration day with Church bells ringing out and more spectacular processions where people line the streets carrying statues of the Risen Christ with bands playing festive tunes. -

December 2020

1 THE MALTESE PRESENCE IN NORTH AMERICA E-NEWSLETTER Issue 21 DECEMBER 2020 PART OF THE MALTESE NATIVITY EXHIBIT, MUSEUM OF THE BIBLE Courtesy of the Embassy of the Republic of Malta to the United States – see page 20 2 The Maltese Presence material and number of breaking years, just as Thanksgiving in North America news items, such as the imposi- wasn’t for Canadians in October Issue No. 21 December 2020 tion of colour-coded levels in the or Americans in November. Editor Province of Ontario and the May you have a Merry Christ- Dan Brock Greater Toronto Area being mas and a Happy New Year from downgraded to code red during our house to yours. Copy Editor this pandemic and Fr. Ivan Mona Vella Nicholas Camilleri being appointed an auxiliary bishop for the Arch- Contributors to This Issue diocese of Toronto by Pope CANADA Francis. Ontario As well as great single-issue Consulate General of Malta to accounts of individuals or fami- Canada webpage lies, there have been multi-issue Richard S. Cumbo accounts such as that on Alphon- CONTENTS Carla Letch so F. Cutaiar, Jr. by Gabrielle Cu- 2. Editorial Comment Fr. Mario Micallef tair Caldwell of Maryland, on 3. Pastor’s Thoughts… USA Carmelo Borg by Carmela Borg 4. Malta-North America Michigan of Ohio and, beginning in this Business Council Launched Mike Cutajar issue, on Felix Cutajar by Mike 5. Maltese Pumpkin Pie (Torta Lisa LiGreci Cutajar Tal-Qara Ħamra) Washington, DC It was suggested that Maltese 9. A Unique Exhibition on Malta Ambassador Keith Azzopardi recipes be featured. -

Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960 Marc Anthony Sanko Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sanko, Marc Anthony, "Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6565. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6565 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960 Marc Anthony Sanko Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Kenneth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D., Chair James Siekmeier, Ph.D. Joseph Hodge, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Mary Durfee, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2018 Keywords: Immigration History, U.S. -

CONSTRUCTUYG NATIONAL Hlstory at PIER 21

CONSTRUCTUYG NATIONAL HlSTORY AT PIER 21 National Library ~lmnationale l*l of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acq$siiimet Bibliographic Sewices se- bPkgtaphqu85 395 Wellington Street 395. Onawa ON KIA ON4 -W KlAW4 Canada Cuirdi The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence aüowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Cana& to Bhiiothbque nationale du Canada & reproduce, lom, distriiute or se1 reprodriire,prêter,disûi'bnerou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. Ia forme de microfiche/fiim, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat électnmique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neitha dre droit d'auteur qPi protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial exmds hmit Ni lathèse ni des exûaits substanîieis may be printed or othexwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. lzida Zorde Mmters of Ar@ 2001 Ontario lnstitute for Snidin im EdamLian aftbe Usiversity of Toronto This research examines how national historical mmtiyes help amîwt bth bwwe sce the past and how we interpret and act upon our paent cùemstances. This study focuses on Pier 7 1 as a site in Canada where immigdm and Cadian hisîary are taught and exhibited through the reconstruction of immigrant "expericllce*. Between 1928 and 197 !. Pier 2 1 was one of the major Canadian ports of emy for immigrants. In this thesis, 1 examine the Pier 2 1 exhibit and the institutionai relations at work in its poduction and continual operation. -

Fr. Fortunato Mizzi's Contributions to Maltese Catholics in Toronto1

CCHA, Historical Sudies, 67 (2001), 57-80 Fr. Fortunato Mizzi’s Contributions to Maltese Catholics in Toronto1 John P. PORTELLI The efforts and role of the Catholic Church in the development of non-English speaking immigrant communities who settled in Toronto at the end of the 19th century and the first three decades of the twentieth century is generally well documented.2 There is also a rather impressive literature on the growth and struggles of ethnic parishes in Toronto during this same period.3 This research includes work on the contribution 1 I would like to thank Robert Berard (Mount St. Vincent University) for encouraging me to write this paper. I also thank Elizabeth Smyth (OISE/UT), Roberto Perin (York University), and the three anonymous reviewers for comments and suggestions on an earlier version of this paper. The research for this paper was supported by research grants from Mount St. Vincent University (1997), Acadia University (1998), and The University of Toronto (2000). 2 See, for example, Luigi Pautasso, “Archbishop Fergus P. McEvay and the Betterment of Toronto’s Italians,” Italian Canadiana, 5, 1989, 56-103; Mark G. McGowan, “Toronto’s English-Speaking Catholics, Immigration, and the Making of a Canadian Catholic Identity, 1900-30,” in T. Murphy and G. Stortz (Eds.) Creed and Culture: The Place of English-Speaking Catholics in Canadian Society, 1750-1930 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993), 204-45; Linda F. Wicks, “‘There Must Be No Drawing Back’: the Catholic Church’s Efforts on Behalf of Non-English Speaking Immigrants in Toronto 1889-1939 ” (M.A. -

Shift of Maltese Migrants in Toronto : Afollow-Upto Sciriha1

LANGUAGE~NTENANCEANDLANGUAGE SHIFT OF MALTESE MIGRANTS IN TORONTO : AFOLLOW-UPTO SCIRIHA1 HANNAH SLAVIK Abstract - This author investigates the levels of language maintenance and language shift among Maltese-Canadian immigrants living in Toronto, Ontario. The authors research on language use is compared with a simi lar study carried out by Sciriha in 1989. The results of the more recent study show that the Maltese language is used widely among first genera tion migrants, but the majority of second generation respondents do not use Maltese in many domains, ifat all. Although most respondents believe that it is important to maintain the Maltese language and pass it on to their children, few actually speak Maltese to their children. As predicted by Sciriha (1989) the process of shift from Maltese to English is well underway for the Maltese living in Toronto. Introduction During the decades following the Second World War, thousands of Maltese emigrated to Australia (York 1986, 1990), the United Kingdom (Attard 1998; Dench 1975), the United States (Attard 1983, 1989, 1997) and Canada (Attard 1983, 1989, 1997; Bonavia 1980). In Canada, most joined the small but well-established community of Maltese in the Junction area_ of Toronto. The Maltese in Canada were faced with the same question that faces all immi grant communities : how can the immigrant community maintain some thing of its cultural heritage and identity and at the same time integrate into the host society? The Maltese in Canada have established an ethnic church, clubs, Maltese language press, radio, television and a language school in order to help maintain their cultural heritage. -

Maltese-Canadian Victor Micallef Shines with the Canadian Tenors Story About This Talented Toronto Resident on Page 6

FMLA Newsletter Issue 12 September 2011 Maltese-Canadian Victor Micallef Shines with The Canadian Tenors Story about this talented Toronto resident on page 6. From the Editor’s Desk: MORE Music In Our Lives Not long ago in the Maltese Link, I wrote about the important role music always has in the lives of Maltese emigrants, describing the many family and social events that took place in New York City when my mother was growing up. Today, we leave New York and go to Toronto to meet Victor Micallef, a Maltese-Canadian, who is part of the Canadian Tenors. Victor began his music training at the piano was he was four, but he also liked singing. Very shy by his own admission, Victor‟s father, the late Joe encouraged him to sing at St. Paul‟s Church, in Toronto‟s Maltese community. He sang solo in the choir at Mass and also at weddings, funerals, and special programs at the church. Sadly, his father passed away when he was 16, but Micallef kept on with the piano lessons and singing. It was this early nurturing in the Toronto Maltese community, he says, that was instrumental in who he is today and what he is doing. When he was 16, Victor began formal voice lessons and later went on to the University of Western Ontario and the University of Toronto to earn a Bachelor‟s degree in vocal performance. Flash forward: This once shy performer is now one of the Canadian Tenors, an ensemble of four men who have mesmerized audiences throughout the world with their solo and collective voices. -

New Perspectives the IV Convention for the Maltese

New Perspectives The IV Convention for the Maltese Living Abroad 20th – 23rd April 2015 Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Valletta, Malta 1 Cataloguing in Publication IV Convention for Maltese living abroad (2015). New perspectives : convention for the Maltese living abroad 20th - 23rd April 2015. – Valletta : Ministeru tal-Affarijiet Barranin, 2016. 452 p. ; cm. ISBN 978-99957-41-03-7 1. Malta-Emigration and immigration-Congresses. I. Malta-Ministeru tal-Affarijiet Barranin. II. Title. 304.8094585-dc23. Ippubblikat mill-Ministeru tal-Affarijiet Barranin, Il-Belt Valletta, Malta Published by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Valletta, Malta © Ministeru tal-Affarijiet Barranin, Malta www.foreignaffairs.gov.mt ISBN: 978-99957-41-03-7 Stampat u mitbugħ fl-Istamperija tal-Gvern Printed by the Government Press 2 Kumitat Organizzattiv Organising Committee Chairperson: Fiona FORMOSA Permanent Secretary Ministry for Foreign Affairs Members: Olaph TERRIBILE Private Secretary to the Hon Minister Ministry for Foreign Affairs Rosette SPITERI-CACHIA Assistant Private Secetary to the Hon Minister Ministry for Foreign Affairs Cataloguing in Publication Etienne ST. JOHN Communications Coordinator to the Hon. Minister IV Convention for Maltese living abroad (2015). Ministry for Foreign Affairs New perspectives : convention for the Maltese living abroad 20th - 23rd April 2015. – Valletta : Ministeru tal-Affarijiet Helga MIZZI Barranin, 2016. Director-General – Political, EU Affairs and Maltese Abroad Ministry for Foreign Affairs 452 p. ; cm. Angele AZZOPARDI -

October 2019

1 THE MALTESE PRESENCE IN NORTH AMERICA E-NEWSLETTER Issue 7 OCTOBER 2019 DR. RAYMOND XERRI (centre), CONSUL GENERAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF MALTA (CANADA) CHAIRED AN INTRODUCTORY MEETING WITH THE MALTESE COMMUNITY LEADERS FOR VARIOUS ORGANIZATIONS AS REPRESENTED IN THE MALTESE CANADIAN FEDERATION (MCF), EST. 1974, CANADA’S UMBRELLA MALTESE CANADIAN ORGANIZATON (l. to r., August 15, 2019) Philip Abela (Pres., Festa San Gorg Association), Brandon Azzopardi (Pres., Maltese Canuck/Melita Soccer Team), Paul Portelli (Pres., Gozo Club of Toronto), Jason Mercieca (Rep. Maltese Canadian Business & Networking Association), Dr. Raymond Xerri, Joe Sherri (Pres. Maltese Canadian Federaton), Fr. Mario Micallef, MSSP (Pastor, St. Paul the Apostle Parish), Gisell Sherri (Rep. Maltese Canadian Business & Networking Association), Teresa Bugelli (Rep. Maltese Culture Club of Durham), Carl Azzopardi (Rep., Maltese Canuck/Melita Soccer Team) 2 EDITORIAL COMMENT his notice of the expansion of the Finally, I’ve gotten around to weekly Maltese-language, televi- attempting to list the various sion program into western Canada Maltese clubs in North America. (page 18), and his visits with the (page 25) executive members of the Maltese The back of the journal, page 28, Canadian Federation (page 1) and has a full-page notice of the annual the Gozo Club of Toronto and the Lehen Malti Gala. I can personally Festa San Gorg Association of attest to it being an event well worth Toronto (page 20). attending and for a worthy cause. Dr. Charles Farrugia, Director of My thanks goes out to the many the National Archives of Malta, was individuals who have helped to Dan Brock in the GTA in the latter part of make this issue possible, to those Once again, so much has taken August and early September and, who contributed materials, who place, particularly in the Greater with Dr. -

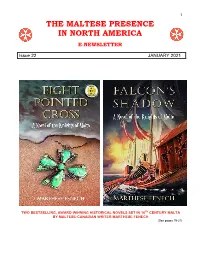

January 2021

1 THE MALTESE PRESENCE IN NORTH AMERICA E-NEWSLETTER Issue 22 JANUARY 2021 TWO BESTSELLING, AWARD-WINNING HISTORICAL NOVELS SET IN 16TH CENTURY MALTA BY MALTESE-CANADIAN WRITER MARTHESE FENECH (See pages 19-21) 2 The Maltese Presence This newsletter would be the poor- nadian who for many years called in North America er were it not for the research “The Junction” home. Issue No. 22 January 2021 assistance provided by people like Marthese Fenech learned of me Editor Mark Caruana and Charles Said- through Richard Cumbo and I was Dan Brock Vassallo of Metropolitan Sydney, inspired to write an article on her NSW, Australia and the ongoing and her two historical novels. Copy Editor permission by Dr. Charles Farrugia I wish to conclude by extending to Mona Vella Nicholas to publish documents from the each of you all the best in the new National Archives of Malta. Closer year and pray to God that we may Contributors to This Issue to home, Richard S. Cumbo of get this current worldwide pandem- CANADA Toronto has been of invaluable ic under control so that our lives Ontario assistance with advice and items may return to normal. Joanne Camilleri for the newsletter. Again, I invite you to contact me at Consulate General of Malta to Fr. Mario Micallef, MSSP, pastor [email protected], be it ideas Canada webpage of St. Paul the Apostle Parish, you wish to share, wishing to be put Marthese Fenech Toronto, like his predecessor, Fr. on the free, bcc, electronic mailing Mel Hamelin Manuel Parnis, MSSP, has been list, etc. -

The Maltese Presence in North America

1 THE MALTESE PRESENCE IN NORTH AMERICA E-NEWSLETTER Issue 16 JULY 2020 Façade of the Original St. Paul of the Shipwreck Church, 1940 Front Cover of 1962 Booklet Relating to St. Paul of the Shipwreck Parish, San Francisco Showing the Architect’s Sketch of the New Church Courtesy of Fred Aquilina 2 The Maltese Presence Ministry for Foreign and European portion of this page.) in North America Affairs for the Maltese living Two of the articles in the works for Issue No. 16 July 2020 throughout all North America. the August issue are on the lives of Editor This issue of the newsletter Monsignor Paul J. Gauci of the Dan Brock contains three items pertaining to Diocese of New Orleans and later charter flights between Toronto and Baton Rouge, Louisiana and Copy Editor Malta in years past (pages 5-7) and Carmelo Borg of Detroit. Carmelo’s Mona Vella-Nicholas travel agencies in Toronto and in family life and family background London, Ontario catering to the were not those of the typical Contributors to This Issue Maltese in 1980 (pages 7, 24). married, Maltese male immigrant to CANADA From the other side of the North America following the Second Ontario continent we have the account of World War. Consulate General of Malta to St. Paul of the Shipwreck Church Canada webpage when it was the heart and soul of Richard S. Cumbo the Maltese community in and Helen Gaffan around San Francisco. (See pages Janene Gaffan 1, 7-10.) Jim Gaffan The second part of the account of Kay Gaffan the Gaffan family of Kingsville, Fr. -

The Maltese Community in Toronto: a Proposed Adult Education Strategy

Title: The Maltese community in Toronto: A proposed adult education strategy. By: Borg, Carmel, Camilleri, Jennifer, Convergence, 00108146, 1995, Vol. 28, Issue 1 THE MALTESE COMMUNITY IN TORONTO: A PROPOSED ADULT EDUCATION STRATEGY In this article, we focus on the Maltese community in Toronto, Canada which, we argue, is suffering from a particular kind of oppression that is given little or no consideration in the existing literature. We name this oppression as that of small nation identity. The trivialization of small countries in the minds of ethnocentric individuals, and institutions/ organizations, has a strong bearing on the subjectivity of immigrants from these places of origin. By highlighting aspects of everyday life experienced by members of the Maltese community, the voice of a subordinate group is reclaimed, providing visibility to a community which has hitherto been invisible, its voice having been immersed in the "culture of silence". We also aim to explore the contradictory discourses that characterize the community. In the second half of the paper we propose an adult education strategy intended to affirm the roots of this community and provide the basis for better democratic living within the larger Toronto community. The marginalization of the Maltese experience is institutionalized. The Council of Europe, for instance, classifies Malta as a "peripheral" country. The obvious connotation, given that the notion of periphery implies the existence of a centre, is that the fulcrum of mainstream European activity would be in Central Europe and Great Britain. The notion of periphery is re-echoed in the physical location of what has come to be regarded as the hub of the Maltese community in Metro Toronto.