Cornwall HLC Type

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Development Site, Treetops, the Square, Week St

Residential development site, Treetops, The Square, For Sale Guide Price £1,400,000 Week St. Mary, Near Bude, Cornwall, EX22 6UH EPC: Exempt Level site in the centre of the village extending to approximately 3.59 acres. Planning permission for 28 residential dwellings, public house and conversion of the existing bungalow. Section 106 agreement with a requirement for 7 affordable dwellings on site. Located in North Cornwall being 5 miles away from the Coastline. [email protected] chestertonhumberts.com Location & Description Treetops holiday park is well located in the centre of the village of Week St.Mary, near to the North Cornwall and Devon coastline with Dartmoor National Park being easily accessible. The village include church, store/post office and parish hall. Further amenities and facilities can be found at the coastal resort of Bude, 6 miles away. Cornwall Council has granted planning permission on the 22nd June 2016 for the demolition of the existing buildings and the construction of 28 new dwellings and a pub/café/community room and the conversion of the retained bungalow (planning reference PA15/08783). Section 106 Agreement Launceston known as the ‘gateway to Cornwall’ is situated The planning consent includes a section 106 agreement 11.5 miles to the South offering extensive shopping facilities, which requires 7 affordable dwellings with 3 affordable whilst Holsworthy with its traditional local shops and rentals at 80% of the open market rent (2 x 1 bedroom flat and Waitrose supermarket is 9 miles away. 1 x 2 bedroom house) and 4 x shared ownership (3 x 2 bed and 1 x 3 bed). -

Truro 1961 Repairs BLISLAND St

Locality Church Name Parish County Diocese Date Grant reason BALDHU St. Michael & All Angels BALDHU Cornwall Truro 1961 Repairs BLISLAND St. Pratt BLISLAND Cornwall Truro 1894-1895 Reseating/Repairs BOCONNOC Parish Church BOCONNOC Cornwall Truro 1934-1936 Repairs BOSCASTLE St. James MINSTER Cornwall Truro 1899 New Church BRADDOCK St. Mary BRADDOCK Cornwall Truro 1926-1927 Repairs BREA Mission Church CAMBORNE, All Saints, Tuckingmill Cornwall Truro 1888 New Church BROADWOOD-WIDGER Mission Church,Ivyhouse BROADWOOD-WIDGER Devon Truro 1897 New Church BUCKSHEAD Mission Church TRURO, St. Clement Cornwall Truro 1926 Repairs BUDOCK RURAL Mission Church, Glasney BUDOCK RURAL, St. Budoc Cornwall Truro 1908 New Church BUDOCK RURAL St. Budoc BUDOCK RURAL, St. Budoc Cornwall Truro 1954-1955 Repairs CALLINGTON St. Mary the Virgin CALLINGTON Cornwall Truro 1879-1882 Enlargement CAMBORNE St. Meriadoc CAMBORNE, St. Meriadoc Cornwall Truro 1878-1879 Enlargement CAMBORNE Mission Church CAMBORNE, St. Meriadoc Cornwall Truro 1883-1885 New Church CAMELFORD St. Thomas of Canterbury LANTEGLOS BY CAMELFORD Cornwall Truro 1931-1938 New Church CARBIS BAY St. Anta & All Saints CARBIS BAY Cornwall Truro 1965-1969 Enlargement CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1896 Repairs CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1907-1908 Reseating/Repairs CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1943 Repairs CARHARRACK Mission Church GWENNAP Cornwall Truro 1882 New Church CARNMENELLIS Holy Trinity CARNMENELLIS Cornwall Truro 1921 Repairs CHACEWATER St. Paul CHACEWATER Cornwall Truro 1891-1893 Rebuild COLAN St. Colan COLAN Cornwall Truro 1884-1885 Reseating/Repairs CONSTANTINE St. Constantine CONSTANTINE Cornwall Truro 1876-1879 Repairs CORNELLY St. Cornelius CORNELLY Cornwall Truro 1900-1901 Reseating/Repairs CRANTOCK RURAL St. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

Residential Development of up to 4 Dwellings at Land Adjacent to Bingera Cottage, Madeira Drive, Widemouth Bay {220050, 102402}

Proposed Outline Planning Application for Residential Development of up to 4 Dwellings at Land adjacent to Bingera Cottage, Madeira Drive, Widemouth Bay {220050, 102402} DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT v1.4 prepared by: THE BAZELEY PARTNERSHIP Chartered Architects Efford Farm Business Park Bude, Cornwall EX23 8LT 01288 355557 [email protected] CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION p4 2.0 SITE HISTORY p5 3.0 AMBITIONS p7 4.0 CONTEXT APPRAISAL p8 5.0 USE & AMOUNT p12 6.0 LAYOUT p15 7.0 SCALE & MASSING p19 8.0 APPEARANCE p25 9.0 LANDSCAPING p26 A high-quality proposed residential development of 4no. dwellings distributed as an indicative mix of detached two-storey and ‘room-in-the-roof’ dwellings, each around 10.0 DRAINAGE p28 140m2 in size and with a mix of off-road and garage vehicular parking. The proposal works with the semi-rural settlement location and proposes the continuation 11.0 ECOLOGY p29 of the built form along Madeira Drive with Plots 1-3 adding an element of layering and interest to the street scene through a variation in aesthetics, ridge heights and distances from the highway. 12.0 ACCESS p30 The proposal places an emphasis on rural place-making rather than a high-density layout, with generous gardens / amenity spaces and priority given to retaining and encouraging wildlife through site-wide soft landscaping and permeable boundaries between plots. Land adj. Bingera Cottage, Widemouth Bay DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT THE BAZELEY PARTNERSHIP [email protected] page 2 The Surf House The Phoenix Tek-Chy Sea Quarts Sea Haze -

Cornish Archaeology 41–42 Hendhyscans Kernow 2002–3

© 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society CORNISH ARCHAEOLOGY 41–42 HENDHYSCANS KERNOW 2002–3 EDITORS GRAEME KIRKHAM AND PETER HERRING (Published 2006) CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © COPYRIGHT CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2006 No part of this volume may be reproduced without permission of the Society and the relevant author ISSN 0070 024X Typesetting, printing and binding by Arrowsmith, Bristol © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Contents Preface i HENRIETTA QUINNELL Reflections iii CHARLES THOMAS An Iron Age sword and mirror cist burial from Bryher, Isles of Scilly 1 CHARLES JOHNS Excavation of an Early Christian cemetery at Althea Library, Padstow 80 PRU MANNING and PETER STEAD Journeys to the Rock: archaeological investigations at Tregarrick Farm, Roche 107 DICK COLE and ANDY M JONES Chariots of fire: symbols and motifs on recent Iron Age metalwork finds in Cornwall 144 ANNA TYACKE Cornwall Archaeological Society – Devon Archaeological Society joint symposium 2003: 149 archaeology and the media PETER GATHERCOLE, JANE STANLEY and NICHOLAS THOMAS A medieval cross from Lidwell, Stoke Climsland 161 SAM TURNER Recent work by the Historic Environment Service, Cornwall County Council 165 Recent work in Cornwall by Exeter Archaeology 194 Obituary: R D Penhallurick 198 CHARLES THOMAS © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Preface This double-volume of Cornish Archaeology marks the start of its fifth decade of publication. Your Editors and General Committee considered this milestone an appropriate point to review its presentation and initiate some changes to the style which has served us so well for the last four decades. The genesis of this style, with its hallmark yellow card cover, is described on a following page by our founding Editor, Professor Charles Thomas. -

Environmentol Protection Report WATER QUALITY MONITORING

5k Environmentol Protection Report WATER QUALITY MONITORING LOCATIONS 1992 April 1992 FW P/9 2/ 0 0 1 Author: B Steele Technicol Assistant, Freshwater NRA National Rivers Authority CVM Davies South West Region Environmental Protection Manager HATER QUALITY MONITORING LOCATIONS 1992 _ . - - TECHNICAL REPORT NO: FWP/92/001 The maps in this report indicate the monitoring locations for the 1992 Regional Water Quality Monitoring Programme which is described separately. The presentation of all monitoring features into these catchment maps will assist in developing an integrated approach to catchment management and operation. The water quality monitoring maps and index were originally incorporated into the Catchment Action Plans. They provide a visual presentation of monitored sites within a catchment and enable water quality data to be accessed easily by all departments and external organisations. The maps bring together information from different sections within Water Quality. The routine river monitoring and tidal water monitoring points, the licensed waste disposal sites and the monitored effluent discharges (pic, non-plc, fish farms, COPA Variation Order [non-plc and pic]) are plotted. The type of discharge is identified such as sewage effluent, dairy factory, etc. Additionally, river impact and control sites are indicated for significant effluent discharges. If the watercourse is not sampled then the location symbol is qualified by (*). Additional details give the type of monitoring undertaken at sites (ie chemical, biological and algological) and whether they are analysed for more specialised substances as required by: a. EC Dangerous Substances Directive b. EC Freshwater Fish Water Quality Directive c. DOE Harmonised Monitoring Scheme d. DOE Red List Reduction Programme c. -

Cornwall Local Plan: Community Network Area Sections

Planning for Cornwall Cornwall’s future Local Plan Strategic Policies 2010 - 2030 Community Network Area Sections www.cornwall.gov.uk Dalghow Contents 3 Community Networks 6 PP1 West Penwith 12 PP2 Hayle and St Ives 18 PP3 Helston and South Kerrier 22 PP4 Camborne, Pool and Redruth 28 PP5 Falmouth and Penryn 32 PP6 Truro and Roseland 36 PP7 St Agnes and Perranporth 38 PP8 Newquay and St Columb 41 PP9 St Austell & Mevagissey; China Clay; St Blazey, Fowey & Lostwithiel 51 PP10 Wadebridge and Padstow 54 PP11 Bodmin 57 PP12 Camelford 60 PP13 Bude 63 PP14 Launceston 66 PP15 Liskeard and Looe 69 PP16 Caradon 71 PP17 Cornwall Gateway Note: Penzance, Hayle, Helston, Camborne Pool Illogan Redruth, Falmouth Penryn, Newquay, St Austell, Bodmin, Bude, Launceston and Saltash will be subject to the Site Allocations Development Plan Document. This document should be read in conjunction with the Cornwall Local Plan: Strategic Policies 2010 - 2030 Community Network Area Sections 2010-2030 4 Planning for places unreasonably limiting future opportunity. 1.4 For the main towns, town frameworks were developed providing advice on objectives and opportunities for growth. The targets set out in this plan use these as a basis for policy where appropriate, but have been moderated to ensure the delivery of the wider strategy. These frameworks will form evidence supporting Cornwall Allocations Development Plan Document which will, where required, identify major sites and also Neighbourhood Development Plans where these are produced. Town frameworks have been prepared for; Bodmin; Bude; Camborne-Pool-Redruth; Falmouth Local objectives, implementation & Penryn; Hayle; Launceston; Newquay; Penzance & Newlyn; St Austell, St Blazey and Clay Country and monitoring (regeneration plan) and St Ives & Carbis Bay 1.1 The Local Plan (the Plan) sets out our main 1.5 The exception to the proposed policy framework planning approach and policies for Cornwall. -

Cornwall & Isles of Scilly Landscape Character Study

CORNWALL AND ISLES OF SCILLY LANDSCAPE CHARACTER STUDY Overview and Technical Report Final Report May 2007 Forward The Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Landscape Character Study 2005-2007 has been developed as a joint project between the local authorities in Cornwall, the National Trust and the AONB units of Cornwall, the Tamar Valley and the Isles of Scilly supported by the Countryside Agency (now Natural England). Diacono Associates in conjunction with White Consultants were appointed in 2005 to undertake a Landscape Character Assessment for Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly. This updates the Cornwall Landscape Assessment published in 1994. This report sets out the methodology by which Landscape Character Areas have been identified, based on Landscape Description Units, and brings together the main findings of the study including the initial consultation stages. Part of the study included an assessment of landscape sensitivity at the level of the Landscape Description Units. This aspect of the study is however to be the subject of further investigation and the findings set out in this report have not therefore been endorsed at this stage by the participating organisations. This report will form the basis of a number of areas of further research and investigation including landscape sensitivity, and seascape assessment as well as the further consultation on the draft Landscape Character Area Descriptions. Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Landscape Character Study 2005-2007 Project Management Group Oct 2007 Final Report Cornwall and the Isles of -

Cornwall in the Bronze Age �A��ICIA M� C��IS�IE

CORNISH ARCHAEOLOGY No. 25 (1986) Cornwall in the Bronze Age AICIA M CISIE The Concept of a Bronze 'Age' Any review of the Bronze Age in Cornwall, or indeed in other areas of the British Isles, must today present the writer with a very different prospect to that which lay before Bernard Wailes 28 years ago, although much of the basic information remains the same. We now know, for example, that metallurgy was introduced into these islands before the middle of the third millennium bc, probably from two continental quarters, the Rhineland and the Atlantic region. Our period has lengthened and the calibration of radiocarbon dates means that it not only overlaps the Late Neolithic but also merges into the Iron Age in the mid-first millennium BC, giving a total of some 2000 years. The accumulation of data and dates, togther with advances in excavation and research techniques and the recognition of regional variation, make the whole concept of a Bronze 'age' far more complex than hitherto. In the 1960s, HawkeV scheme for the divisions of the British Bronze Age provided the framework (Hawkes, 1960) and was widely accepted in principle. As more radiocarbon dates have become available, there have nevertheless been surprises and many refinements have been applied, allowing a broader, more flexible approach into which ceramics and metalwork can be fitted. Today the most widely accepted scheme is that propounded by Burgess (in 5/0 wo OE AGE SIES SS 00 SX - 2,0 Fig 1 Location map showing principal sites mentioned in the text. Settlements or occupation -

Edited by IJ Bennallick & DA Pearman

BOTANICAL CORNWALL 2010 No. 14 Edited by I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman BOTANICAL CORNWALL No. 14 Edited by I.J.Bennallick & D.A.Pearman ISSN 1364 - 4335 © I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman 2010 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder. Published by - the Environmental Records Centre for Cornwall & the Isles of Scilly (ERCCIS) based at the- Cornwall Wildlife Trust Five Acres, Allet, Truro, Cornwall, TR4 9DJ Tel: (01872) 273939 Fax: (01872) 225476 Website: www.erccis.co.uk and www.cornwallwildlifetrust.org.uk Cover photo: Perennial Centaury Centaurium scilloides at Gwennap Head, 2010. © I J Bennallick 2 Contents Introduction - I. J. Bennallick & D. A. Pearman 4 A new dandelion - Taraxacum ronae - and its distribution in Cornwall - L. J. Margetts 5 Recording in Cornwall 2006 to 2009 – C. N. French 9 Fitch‟s Illustrations of the British Flora – C. N. French 15 Important Plant Areas – C. N. French 17 The decline of Illecebrum verticillatum – D. A. Pearman 22 Bryological Field Meetings 2006 – 2007 – N. de Sausmarez 29 Centaurium scilloides, Juncus subnodulosus and Phegopteris connectilis rediscovered in Cornwall after many years – I. J. Bennallick 36 Plant records for Cornwall up to September 2009 – I. J. Bennallick 43 Plant records and update from the Isles of Scilly 2006 – 2009 – R. E. Parslow 93 3 Introduction We can only apologise for the very long gestation of this number. There is so much going on in the Cornwall botanical world – a New Red Data Book, an imminent Fern Atlas, plans for a new Flora and a Rare Plant Register, plus masses of fieldwork, most notably for Natural England for rare plants on SSSIs, that somehow this publication has kept on being put back as other more urgent tasks vie for precedence. -

Bude & North Cornwall

Find & Seek in Cornwall: Itinerary & Experience Suggestions Bude & North Cornwall Food & Drink Tintagel Pottery - Traditional ceramic pottery The Beach House – restaurant, bar, music and Pottery Box- small secluded artist studio, private beach access offering workshops Bude Brewery – an independent brewery with Atlantic Glass Workshop- workshop, studio a shop and events and shop. Outdoor & Adventure Heritage & Culture Bude Canoe Experience - Canoeing on The Museum of Witchcraft - a museum dedicated Bude Canal, Roadford Lake, Tamar Lake & to European witchcraft and magic in Boscastle River Torridge Tintagel Castle - history, myths and stunning Walk Bude – a selection of countryside & scenery coastal walks around Bude The Arthurian Centre – a centre dedicated to Shoreline Extreme Sports – coasteering, telling the stories of King Arthur kayaking, surfing and more! Segway Bude Performance Tamar Lakes Country Park The Crackington Institute – village hall venue with regular events Art & Craft Cornish Rock Tors – wild swimming, Miss Ivy Events - The South West’s leading coasteering sea kayaking organiser of vintage, lifestyle, pet and artisan events For accommodation listings & inspiration, please contact Visit Cornwall & The Islands’ Partnership For up to date events listings in Cornwall, visit www.cornwall365.com Find & Seek in Cornwall: Itinerary & Experience Suggestions Launceston & East Cornwall Outdoor & Adventure and pottery. Cowslip is a working organic New Mills Farm Park – fun family day out at farm, with an award winning café, shop and the final stop of the Launceston Steam accommodation. Railway Calstock Arts - A community arts centre Tamar Otter & Wildlife Centre - 19 acres of located in a beautifully converted Chapel on landscaped grounds with otters, deer and the banks of the River Tamar birds of prey Hidden Valley Discovery Park & Gardens – Food & Drink family attraction with a treasure hunt, play Coombeshead Farm- guesthouse, restaurant area, Forbidden Mansion and more! and bakery set in grounds and woodlands. -

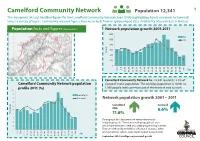

Camelford Community Network Population 12,341

across a variety of topics. Community network figures have been built from neighbourhood data. Availability of parish data is limited. is data parish of Availability data. neighbourhood from built been have figures network Community topics. of avariety across Cornwall to compares it how highlighting (CNA) Area Network Community Camelford the for figures headline out sets document This Network Community Camelford Percentage 10 Population 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0-4 (%) profile2011 Camelford Community Network population 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24 facts and figures figures facts and 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 (Census 2011) 70-74 75-79 80-84 85+ Cornwall Camelford Age September 2014 [email protected] September 2014 (LSOA). Areas Output Super Lower called sometimes and (ONS) Statistics National of the by Office defined are They them. 3,000in and people living between 1,000 have which areas geographical small are These ‘neighbourhoods’. to reference make we document this Throughout Network population growth 2001 –2011 2001 growth population Network 1,380 people (net) commute out of the network area to work. to area network the of out commute (net) people 1,380 so 10,961 is population workday The population. total Cornwall’s Network Community Camelford People growth2001-2011 population Network 10 12 20 40 60 80 00 00 0 0 0 0 0 11.6% CNA Camelford 0-4 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24 Population 12,341 Population 25-29 30-34 35-39 has 12,341 residents; 2.3% of of 2.3% residents; 12,341 has 40-44 45-49 50-54 6.6% Cornwall 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 20 20 11 85+ 01 Age 1 Access to services – Housing 2 Home ownership (%) (Census 2011) 471 households live in social rented housing in the Camelford CNA which is Private Camelford CNA lower (8.9%) than the Cornwall average (12%) as shown in the chart left.