I Am the Doctor, Whether You Like It Or Not

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Mar Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18MAR 2013 MAR COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Mar Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 3:35:28 PM Available only STAR WARS: “BOBA FETT CHEST from your local HOLE” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! MACHINE MAN THE WALKING DEAD: ADVENTURE TIME: CHARCOAL T-SHIRT “KEEP CALM AND CALL “ZOMBIE TIME” Preorder now! MICHONNE” BLACK T-SHIRT BLACK HOODIE Preorder now! Preorder now! 3 March 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 2/7/2013 10:05:45 AM X #1 kiNG CoNaN: Dark Horse ComiCs HoUr oF THe DraGoN #1 Dark Horse ComiCs GreeN Team #1 DC ComiCs THe moVemeNT #1 DoomsDaY.1 #1 DC ComiCs iDW PUBlisHiNG THe BoUNCe #1 imaGe ComiCs TeN GraND #1 UlTimaTe ComiCs imaGe ComiCs sPiDer-maN #23 marVel ComiCs Mar13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 2:21:38 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 2 #1 l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT Uber #1 l AVATAR PRESS Suicide Risk #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Clive Barker’s New Genesis #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Marble Season HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Black Bat #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 1 Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grimm #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Wars In Toyland HC l ONI PRESS INC. The From Hell Companion SC l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Valiant Masters: Shadowman Volume 1: The Spirits Within HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Rurouni Kenshin Restoration Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Soul Eater Soul Art l YEN PRESS BOOKS & MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who: Who-Ology Official Miscellany HC l DOCTOR WHO / TORCHWOOD Doctor Who: The Official -

MT337 201102 Earthshock

EARTHSHOCK By Eric Saward Mysterious Theatre 337 – Show 201102 Revision 3 By the usual suspects Transcription by Robert Warnock (1,2) and Steven W Hill (3,4) Theme starts Didn’t we just do this one? Stars More stars Bright stars Peter! Hey it’s that guy from the Gallifrey convention video. Peter zooms towards camera I saw a guy who looks just like him in the hotel. More bright stars Neon logo Neon logo zooms out Earthshock I love one-word titles. By Eric Saward Part One Star One. Long shot of the BBC Quarry. © Some people in coveralls rappel up the side of a hill. If that’s tug of war, you’re doing it wrong. I love the BBC quarry. Lieutenant Scott reaches out to help Professor Kyle Another boring planet in the middle of nowhere. over the top. She gasps. They run away from the camera towards another hill Is this Halo? where some other troopers are standing guard. They run past an oval-shaped, blue tent to where some other troopers are standing, and stop. Scott looks around a bit, the moves forward again. He heads towards a “tunnel” entrance where some more troopers are standing. Kyle and Snyder are looking into the entrance as Scott walks up. Look, she’s got headlights. Phwooar! Page 1 SNYDER Nothing. Kyle turns around and walks away from the tunnel Quarry. entrance very slowly. PROF KYLE How does this thing work? It’s called a microfiche. WALTERS It focuses upon the electrical activity of the body-heartbeat, things like that. -

Issue 30 Easter Vacation 2005

The Oxford University Doctor Who Society Magazine TThhee TTiiddeess ooff TTiimmee I ssue 30 Easter Vacation 2005 The Tides of Time 30 · 1 · Easter Vacation 2005 SHORELINES TThhee TTiiddeess ooff TTiimmee By the Editor Issue 30 Easter Vacation 2005 Editor Matthew Kilburn The Road to Hell [email protected] I’ve been assuring people that this magazine was on its way for months now. My most-repeated claim has probably Bnmsdmsr been that this magazine would have been in your hands in Michaelmas, had my hard Wanderers 3 drive not failed in August. This is probably true. I had several days blocked out in The prologue and first part of Alex M. Cameron’s new August and September in which I eighth Doctor story expected to complete the magazine. However, thanks to the mysteries of the I’m a Doctor Who Celebrity, Get Me Out of guarantee process, I was unable to Here! 9 replace my computer until October, by James Davies and M. Khan exclusively preview the latest which time I had unexpectedly returned batch of reality shows to full-time work and was in the thick of the launch activities for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Another The Road Not Taken 11 hindrance was the endless rewriting of Daniel Saunders on the potentials in season 26 my paper for the forthcoming Doctor Who critical reader, developed from a paper I A Child of the Gods 17 gave at the conference Time And Relative Alex M. Cameron’s eighth Doctor remembers an episode Dissertations In Space at Manchester on 1 from his Lungbarrow childhood July last year. -

Doctor Who at the BBC: Lost Treasures: Volume 8 Free

FREE DOCTOR WHO AT THE BBC: LOST TREASURES: VOLUME 8 PDF David Darlington,Louise Jameson | 1 pages | 03 Oct 2013 | BBC Audio, A Division Of Random House | 9781471305061 | English | London, United Kingdom Eye of Horus | Doctor Who | Merchandise - BBC AUDIOBOOKS - THE LOST TV EPISODES Collection 1 Dragonfire was the fourth and final serial of season 24 of Doctor Who. It marked the departure of companion Melanie Bushthe return and final appearance of Sabalom Glitzand featured the debut of Sophie Aldred as Ace. As trouble brews on the space trading colony of Iceworldthe Doctor and Mel encounter their sometimes-ally Sabalom Glitz - and a new friend who goes by " Ace ". Iceworld is a space-trading colony on the dark side of the planet Svartos, controlled by the callous and vindictive Kane. He buys supporters and employees and makes them wear his mark iced into their flesh. Kane's body is so cold that one touch from him can kill. In his lair is a vast cryogenic section. Mercenaries and others are frozen and stored, losing their memories to become an unquestioning army. Kane stays there when he needs to cool down. There is also an aged sculptor carving a statue from the ice. He owes Kane a serious amount of money, and if he doesn't return his debt soon he'll lose his ship. Glitz has come to look for a treasure guarded by a dragon in the icy caverns beyond Iceworld. Glitz has a map he won in a game of cards. Kane wanted him to have the map because he wishes to use Glitz in his own search for the treasure. -

A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM of DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected]

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Zepponi, Noah. (2018). THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of the Pacific Communication University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 3 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi APPROVED BY: Thesis Advisor: Marlin Bates, Ph.D. Committee Member: Teresa Bergman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Department Chair: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. 4 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my father, Michael Zepponi. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is here that I would like to give thanks to the people which helped me along the way to completing my thesis. First and foremost, Dr. -

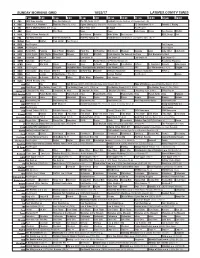

Sunday Morning Grid 10/22/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/22/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Carolina Panthers at Chicago Bears. (N) 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating ISU Grand Prix: Rostelecom Cup. F1 Countdown (N) Å Formula 1 Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Arizona Cardinals vs Los Angeles Rams. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Frank Sinatra: The Voice of Our Time Burt Bacharach’s Best 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Transcript of Doctor

1 You’re listening to Imaginary Worlds, a show about how we create them and why we suspend our disbelief, I’m Eric Molinsky. There’s a bar called The Way Station, which is near my home in Brooklyn. From the outside, it looks like a normal bar. But when you go in, something pops right out at you. A blue Police Box. ANDY: Every day I open up the shutters and I see her sitting in the corner it's just like I feel like home. That’s because the owner of the bar, Andy Heidel, is a huge Doctor Who fan. Even if you’ve never watched Doctor Who, you probably know that police box has something to do with it. You might also notice that Doctor Who is playing on the back wall, all the time – usually an episode from the mid 2000s when David Tennant played the Doctor. Every fan has “their Doctor.” David Tennant is Andy’s favorite. He’s my favorite Doctor too. ANDY: And nobody can say I'm sorry like Tennant like if I if I'm dying I'm on my deathbed I make a wish foundation that is for him to come and told me I'm sorry. THE DOCTOR: I’m sorry. I’m so sorry So what does the Police Box have to do with Doctor Who? On the show, it’s a ship called the TARDIS. And it may look like a police box on the outside but it’s optical illusion meant to disguise the giant space ship on the inside. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Doctor Who and the Genesis of the Daleks

DOCTOR WHO AND THE GENESIS OF THE DALEKS By Terrance Dicks 1 SECRET MISSION It was a battlefield. The ground was churned, scarred, ravaged. Nothing grew there, nothing lived. The twisted, rusting wrecks of innumerable war machines littered the landscape. There were strands of ragged, tangled wire, collapsed dugouts, caved-in trenches. The perpetual twilight was made darker by fog. Thick, dank and evil, it swirled close to the muddy ground, hiding some of the horrors from view. Something stirred in the mud. A goggled, helmeted head peered over a ridge, surveyed the shattered landscape. A hand beckoned, and more shapes rose and shambled forward. There were about a dozen of them, battle-weary men in ragged uniforms, their weapons a strange mixture of old and new, their faces hidden by gas masks. A star shell burst over their heads, bathing them for a moment in its sickly green light before it sputtered into darkness. The thump of artillery came from somewhere in the distance, with the hysterical chatter of automatic weapons. But the firing was some distance away. Too tired even to react, the patrol shambled on its way. A man materialized out of the fog and stood looking in bewilderment after the soldiers. He was a very tall man, dressed in comfortable, old tweed trousers and a loosely hanging jacket. An amazingly long scarf was wound round his neck, a battered, broad-rimmed hat was jammed onto a tangle of curly brown hair. Hands deep in his pockets, he pivoted slowly on his heels, turning in a complete circle to survey the desolate landscape. -

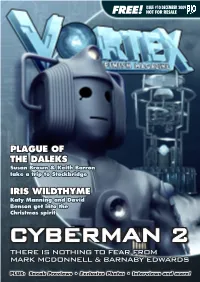

Plague of the Daleks Iris Wildthyme

ISSUE #10 DECEMBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE PLAGUE OF THE DALEKS Susan Brown & Keith Barron take a trip to Stockbridge IRIS WILDTHYME Katy Manning and David Benson get into the Christmas spirit CYBERMAN 2 THERE IS NOTHING TO FEAR FROM MARK MCDONNELL & barnaby EDWARDS PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL THE BIG FINISH SALE Hello! This month’s editorial comes to you direct Now, this month, we have Sherlock Holmes: The from Chicago. I know it’s impossible to tell if that’s Death and Life, which has a really surreal quality true, but it is, honest! I’ve just got into my hotel to it. Conan Doyle actually comes to blows with Prices slashed from 1st December 2009 until 9th January 2010 room and before I’m dragged off to meet and his characters. Brilliant stuff by Holmes expert greet lovely fans at the Doctor Who convention and author David Stuart Davies. going on here (Chicago TARDIS, of course), I And as for Rob’s book... well, you may notice on thought I’d better write this. One of the main the back cover that we’ll be launching it to the public reasons we’re here is to promote our Sherlock at an open event on December 19th, at the Corner Holmes range and Rob Shearman’s book Love Store in London, near Covent Garden. The book will Songs for the Shy and Cynical. Have you bought be on sale and Rob will be signing and giving a either of those yet? Come on, there’s no excuse! couple of readings too. -

Rich's Notes: the Ten Doctors: a Graphic Novel by Rich Morris 102

The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 5 102 Rich's Notes: Since the Daleks are struggling to destroy eachother as well as their attackers, the advantage goes to the Federation forces. Things are going well and the 5th Doctor checks in with the 3rd to see how the battle is playing out. The 3rd Doctor confirms that all is well so far, but then gets a new set of signals. A massive fleet of Sontaran ships unexpectedly comes out of nowhere, an the Sontaran reveal a plot to eliminate the Daleks, the Federation fleet AND the Time Lords! The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 5 103 Rich's Notes: The 3rd Doctor is restrained by the Sontarans before he can warn the fleet. The 5th Doctor tries as well, but the Master has jammed his signal. The Master explains how he plans to use his new, augmented Sontarans to take over the universe. The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 5 104 Rich's Notes: Mistaking the Sontarans as surprise allies hoping to gain the lion’s share of the glory, the Draconian Ambassador and the Ice Warrior general move to greet them as befits their honour and station. But they get a nasty surprise when the Sontarans attack them. The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 5 105 Rich's Notes: The Master, his plot revealed, now uses the sabotaged computer to take over control of the 5th Doctor’s ship. He uses it to torment his old enemy, but causing him to destroy the Federation allies.