UNHCR Submission Estonia UPR 10Th Session

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egovernment in EE

Country Profile Highlights Strategy inside Legal Framework Actors Infrastructure Services for Citizens Services for Businesses What’s eGovernment in Estonia ISA² Visit the e-Government factsheets online on Joinup.eu Joinup is a collaborative platform set up by the European Commission as part of the ISA² programme. ISA² supports the modernisation of the Public Administrations in Europe. Joinup is freely accessible. It provides an observatory on interoperability and e-Government and associated domains like semantic, open source and much more. Moreover, the platform facilitates discussions between public administrations and experts. It also works as a catalogue, where users can easily find and download already developed solutions. The main services are: Have all information you need at your finger tips; Share information and learn; Find, choose and re-use; Enter in discussion. This document is meant to present an overview of the eGoverment status in this country and not to be exhaustive in its references and analysis. Even though every possible care has been taken by the authors to refer to and use valid data from authentic sources, the European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the included information, nor does it accept any responsibility for any use thereof. Cover picture © AdobeStock Content © European Commission © European Union, 2018 Reuse is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged. eGovernment in Estonia May 2018 Country Profile ..................................................................................................... -

OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities His Excellency

OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities His Excellency Mr Toomas Hendrik Ilves Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Estonia Rävala 9 TALLINN EE 0100 Republic of Estonia The Hague Reference no.: 21 May 1997 359/97/L Dear Mr Minister, With great interest I read your statement in the Permanent Council of the OSCE on 10 April 1997 in which you commented on our conversation in Tallinn on 8 April 1997. I was glad to note your positive assessment of the efforts I have made since 1993 to be of assistance to Estonia in solving its inter-ethnic problems. I have also studied carefully the papers prepared by your Ministry and sent to the members of the Permanent Council regarding the issues raised during my visit to Tallinn on 8/9 April 1997 and regarding the recommendations I have made to the Government of Estonia during the period from April 1993 to October 1996. Please allow me to send you a detailed reaction which I will also send to the members of the Permanent Council two weeks after you have received this letter. First of all, I should like to make some general remarks about the situation of the over 200,000 persons in Estonia who have neither the Estonian nor any other citizenship. As I have remarked before, I have found no evidence that persons belonging to national minorities in Estonia are systematically persecuted, or that there are persistent violations of their human rights. The assurance I received in July 1993 from the then Prime Minister, Mr Laar, that Estonia does not intend to start a policy of expulsion from Estonia of Russian speakers has been repeated by subsequent Governments and I feel confident that this will continue to be the case in the future. -

Local Self-Government Reforms in Europe: Legal Aspects of Considering the Communities' Social Identity

Local self-government reforms in Europe: legal aspects of considering the communities' social identity Professor Tetyana SEMIGINA1 Professor Olena MAIDANNYK2 Professor Yuriy ONISCHYK3 Associate professor Yaroslav ZHURAVEL4 Abstract The implementation of local self-government reform is closely linked to the social identity, a concept that includes common territory of residence, history of origin and development, social interaction, moral standards, values, traditions, interests, habits and needs. In order to study the realm of different European countries in implementing of the decentralization policy and the current state of regulation of the local-self government issues with respect to the social identity the comparative-law, formal and legal, and system- structural methods were used. The cross-national comparative study reveals that in Austria, Spain, France, Poland, the formation of local communities’ associations was preceded with regard to the economic criterion and the permission of the executive branch, while the opinion of local communities’ members is only advisory. In Estonia, the legislation regulates the procedure on the formation of unions of townships or cities, as well as a list of issues to be discussed with local communities’ members. However, the decisive move is still left to the government. In Ukraine, it is statutory that a decision to form a united territorial community could be adopted only after positive discussions with members of the relevant local communities. Keywords. social identity, local community, local self-government, local self- government bodies, local government reform. JEL Classification: K23, K30 1. Introduction Society is viewed as a social environment of human existence; it determines the formation of local communities with their own subculture, history and development that reflects their identity. -

Unilateral Acts of States

UNILATERAL ACTS OF STATES [Agenda item 5] DOCUMENT A/CN.4/524 Replies from Governments to the questionnaire: report of the Secretary-General [Original: English/French] [18 April 2002] CONTENTS Page IntroductIon ..................................................................................................................................................................... 85 replIes from Governments to the questIonnaIre General comments ................................................................................................................................................... 86 Question 1. has the State formulated a declaration or other similar expression of the State’s will which can be considered to fall, inter alia, under one or more of the following categories: a promise, recognition, waiver or protest? if the answer is affirmative, could the State provide elements of such practice? ....................................................................................................................................... 86 Question 2. has the State relied on other States’ unilateral acts or otherwise considered that other States’ unilateral acts produce legal effects? if the answer is affirmative, could the State provide elements of such practice? ......................................................................................................................... 89 Question 3. Could the State provide some elements of practice concerning the existence of legal effects or the interpretation of unilateral acts referred to in -

The Russian Minority Issue in Estonia: Host State Policies and the Attitudes of the Population

Polish Journal of Politica l Science Anna Tiido University of Warsaw The Russian minority issue in Estonia: host state policies and the attitudes of the population Abstract The article analyses the recent developments of the relationship between Russian minority in Estonia and its host state. It gives a theoretical background on the minority issue in the triangle of “kin -state/ minority/ host- state”. In Estonia, the principle of Restitution governed the emergence of the Estonian policies. By the end of the 1990s the elites realized that the course towards the integration of the non-Estonian minority should be taken. The mood in the society can be traced from the mostly exclusive citizenship and language policies towards more inclusive course on integration. The author states that after the events of 2014, the attitudes towards the Russian minority were mixed, with some signs of radicalization, but overall there were attempts to include the minority more in the life of the country. Keywords: Russian minority, minorities, Estonia, Russia Vol. 1, Issue 4, 2015 45 Polish Journal of Politica l Science In this article I will analyze the complex relationship between the Russian minority of Estonia and its host state - Estonia. This analysis will take into account the interconnection in the triangle of „kin -state – minority - host-state“, but concentrate on the host state policies and the attitudes of both minority and majority. It is clear that the state of Estonia does not exist in a vacuum, and its policies towards minorities are being largely influenced by the third factor, that of the „kin -st ate“ of Russia. -

DTA Between Estonia-Vietnam Draft

AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF ESTONIA AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF VIET NAM FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME The Government of the Republic of Estonia and the Government of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, Desiring to conclude an Agreement for the avoidance of double taxation and the prevention of fiscal evasion with respect to taxes on income, Have agreed as follows: Article 1 PERSONS COVERED This Agreement shall apply to persons who are residents of one or both of the Contracting States. Article 2 TAXES COVERED 1. This Agreement shall apply to taxes on income imposed on behalf of a Contracting State or of its local authorities, irrespective of the manner in which they are levied. 2. There shall be regarded as taxes on income all taxes imposed on total income or on elements of income, including taxes on gains from the alienation of movable or immovable property, taxes on the total amounts of wages or salaries paid by enterprises. 3. The existing taxes to which the Agreement shall apply are in particular: a) in the case of Estonia, the income tax; (hereinafter referred to as “Estonian tax”) b) in the case of Viet Nam: (i) the personal income tax; and (ii) the business income tax; (hereinafter referred to as “Vietnamese tax”). 4. The Agreement shall apply also to any identical or substantially similar taxes that are imposed after the date of signature of the Agreement in addition to, or in place of, the existing taxes. -

National Intelligence Authorities and Surveillance in the EU: Fundamental Rights Safeguards and Remedies

National intelligence authorities and surveillance in the EU: Fundamental rights safeguards and remedies ESTONIA Version of 1 October 2014 Institute of Baltic Studies Kari Käsper DISCLAIMER: This document was commissioned under a specific contract as background material for the project on National intelligence authorities and surveillance in the EU: Fundamental rights safeguards and remedies. The information and views contained in the document do not necessarily reflect the views or the official position of the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights. The document is made publicly available for transparency and information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or legal opinion. FRA would like to express its appreciation for the comments on the draft report provided by Estonia that were channelled through the FRA National Liaison Office. SUMMARY Description of the surveillance framework [1]. The specific term mass surveillance does not exist in Estonian law, and there is no specific authorisation in Estonian law for mass surveillance measures undertaken by state security or surveillance authorities. [2]. The only measure, according to which information about the whole population or large groups of the population is collected and retained, is so-called metadata retention by telecom and internet companies according to Article 1111 of the Electronic Communications Act (Elektroonilise side seadus , hereinafter ECA), which incorporated into Estonian law Directive 2006/24/EC (Data Retention Directive). The requirements set for the telecom and internet companies by ECA are in some ways stricter than required by the now invalid Data Retention Directive, establishing that the data must be retained in an EU Member State and certain data only in the territory of Estonia. -

Estonia: Phase 1

DIRECTORATE FOR FINANCIAL AND ENTERPRISE AFFAIRS ESTONIA: PHASE 1 REVIEW OF IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CONVENTION AND 1997 REVISED RECOMMENDATION This report was approved and adopted by the Working Group on Bribery in International Business Transactions on 15 February 2006. 1 ESTONIA REVIEW OF IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CONVENTION AND 1997 REVISED RECOMMENDATION A. IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CONVENTION Formal Issues 1. Estonia is the second country, after Slovenia,1 to accede to the 1997 Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions (the “Convention”)2 in compliance with Article 13 of the Convention, which regulates accession.3 Estonia started to be a full participant in the OECD Working Group on Bribery in International Business Transactions (the Working Group) in June 2004, and deposited its instrument of accession on 23 November 2004. The Convention entered into force in Estonia on 22 January 2005. The Convention and the Estonian legal system 2. Estonia’s legal system, including provisions on the fight against transnational bribery, has been characterised by rapid changes in recent years. Today, the criminal legislative framework for combating corruption is principally contained in the 2002 Penal Code, the 1999 Anti-Corruption Act4 and the 2004 Code of Criminal Procedure. 3. The implementing legislation5 came into force on 1 July 2004: Sections 297 and 298 of the Penal Code sanction the active bribery of “officials” and Section 288 defines “officials” as those in Estonia and in foreign countries. Legal persons are liable for the two offences. 4. The Estonian Constitution provides that “If laws or other legislation of Estonia are in conflict with international treaties ratified by the [Parliament], the provisions of the international treaty shall apply.” However, the Estonian authorities do not elaborate on the application of this provision in practice. -

Information Architecture of Estonian Personalised Medicine Pilot Project Ii

Description of the current status and future needs of the Information Architecture and Data Management solutions for the national personalised medicine pilot project CONTRACTING AUTHORITY:MINISTRY OF SOCIAL AFFAIRS PROCUREMENT REFERENCE NUMBER: 160112 TARTU 2015 SULEV REISBERG HARRY-ANTON TALVIK KALEV KOPPEL SVEN LAUR JAAK VILO Software Technology and Applications Competence Centre (STACC) Quretec University of Tartu Information Architecture of Estonian Personalised Medicine Pilot Project ii Copyright © 2015 OÜ Tarkvara Tehnoloogia Arenduskeskus / Software Technology and Applications Competence Centre This developmental research project is commissioned by the Ministry of Social Affairs and carried out by the Software Technology and Applications Competence Centre (STACC), Quretec and University of Tartu from March to June 2015. The project is supported by the European Union Structural Funds via the programme TerVE implemented by the Estonian Research Council. Contact information: OÜ Tarkvara Tehnoloogia Arenduskeskus, Ülikooli 2 (5th floor), Tartu, Estonia; +372 740 7522, [email protected]. Information Architecture of Estonian Personalised Medicine Pilot Project iii Executive summary Since completion of the first sequence of human genome in 2003, followed by a rapid decline in costs of sequencing technologies on one hand and acquisition of deeper knowledge about the genome function on the other, we are nearly there to embrace genomic data as a cost-effective component of routine health service. Several personalised medicine initiatives have been launched all around the world in recent years. Amongst them is an Estonian pilot project for implementing personalised medicine in health care on national scale, planned to start in autumn 2015. This document summarises the preliminary analysis about the current state and future needs for information architecture and data management aspects related to the gradual implementation of the national personalised medicine initiative in Estonia. -

Eesti Majanduspoliitilised Väitlused Estnische Gespräche Über Wirtschaftspolitik Discussions on Estonian Economic Policy

EESTI MAJANDUSPOLIITILISED VÄITLUSED Artiklid (CD-ROM) ja Kokkuvõtted ESTNISCHE GESPRÄCHE ÜBER WIRTSCHAFTSPOLITIK Beiträge (CD-ROM) und Zusammenfassungen DISCUSSIONS ON ESTONIAN ECONOMIC POLICY Articles (CD-ROM) and Summaries XVI 2008 Eesti majanduspoliitilised väitlused − 16 / Estnische Gespräche über Wirtschaftspolitik − 16 / Discussions on Estonian Economic Policy − 16 Asutatud 1984 / Gegründet im Jahre 1984 / Established in 1984 ASUTAJA, KOORDINAATOR JA TOIMETAJA / GRÜNDER, KOORDINATOR UND REDAKTERUR / FOUNDER, COORDINATOR AND EDITOR: Matti Raudjärv (Tartu Ülikool − Pärnu Kolledž ja Mattimar OÜ) KAASKOORDINAATORID JA KONSULTANDID/ KOORDINATIONS- UND BERATUNGSTEAM / CO-COORDINATORS AND CONSULTANTS: Sulev Mäeltsemees (Tallinna Tehnikaülikool) Janno Reiljan (Tartu Ülikool) TOIMETUSKOLLEEGIUM / REDAKTIONSKOLLEGIUM / EDITORIAL BOARD Peter Friedrich (University of Federal Armed Forces Munich, University of Tartu) Manfred O. E. Hennies (Fachhochschule Kiel) Enno Langfeldt (Fachhochschule Kiel) Stefan Okurch (Andrassy Gyula Deutschsprachige Universität Budapest) Armin Rohde (Ernst-Moritz-Arndt Universität Greifswald) Mart Sõrg (Tartu Ülikool) Publikatsioon ilmub kuni kaks korda aastas / Die Publikation erscheint bis zu zwei Mal im Jahr / The publication is published once or twice a year Artiklid on avaldatud andmebaasis ECONIS / Die Beiträge sind in der Datenbank ECONIS / Articles have been published in the ECONIS database KONTAKT − CONTACT: Matti Raudjärv Tartu Ülikool − Pärnu Kolledž / University of Tartu − Pärnu College or Mattimar OÜ -

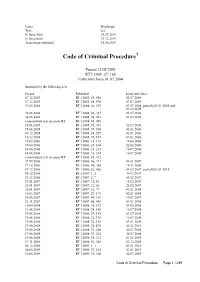

Code of Criminal Procedure1

Issuer: Riigikogu Type: act In force from: 01.07.2019 In force until: 31.12.2019 Translation published: 15.05.2019 Code of Criminal Procedure1 Passed 12.02.2003 RT I 2003, 27, 166 Entry into force 01.07.2004 Amended by the following acts Passed Published Entry into force 17.12.2003 RT I 2003, 83, 558 01.07.2004 17.12.2003 RT I 2003, 88, 590 01.07.2004 19.05.2004 RT I 2004, 46, 329 01.07.2004, partially01.01.2005 and 01.09.2005 28.06.2004 RT I 2004, 54, 387 01.07.2004 28.06.2004 RT I 2004, 56, 403 01.03.2005 consolidated text on paper RT RT I 2004, 65, 456 15.06.2005 RT I 2005, 39, 307 21.07.2005 15.06.2005 RT I 2005, 39, 308 01.01.2006 07.12.2005 RT I 2005, 68, 529 01.01.2006 15.12.2005 RT I 2005, 71, 549 01.01.2006 15.03.2006 RT I 2006, 15, 118 14.04.2006 19.04.2006 RT I 2006, 21, 160 25.05.2006 14.06.2006 RT I 2006, 31, 233 16.07.2006 14.06.2006 RT I 2006, 31, 234 16.07.2006 consolidated text on paper RT RT I 2006, 45, 332 27.09.2006 RT I 2006, 46, 333 01.01.2007 11.10.2006 RT I 2006, 48, 360 18.11.2006 13.12.2006 RT I 2006, 63, 466 01.02.2007, partially01.01.2015 06.12.2006 RT I 2007, 1, 2 30.03.2007 13.12.2006 RT I 2007, 2, 7 01.02.2007 17.01.2007 RT I 2007, 11, 51 18.02.2007 24.01.2007 RT I 2007, 12, 66 25.02.2007 25.01.2007 RT I 2007, 16, 77 01.01.2008 15.02.2007 RT I 2007, 23, 119 02.01.2008 14.06.2007 RT I 2007, 44, 316 14.07.2007 22.11.2007 RT I 2007, 66, 408 01.01.2008 16.04.2008 RT I 2008, 19, 132 23.05.2008 11.06.2008 RT I 2008, 28, 180 15.07.2008 19.06.2008 RT I 2008, 29, 189 01.07.2008 19.06.2008 RT I 2008, 32, 198 15.07.2008 -

Toward an Interpretative Model of Judicial Independence

TOWARD AN INTERPRETIVE MODEL OF JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE: A CASE STUDY OF EASTERN EUROPE DANIEL RYAN KOSLOSKY* 1. INTRODUCTION...........................................................................204 2. JUDICIAL LEGACIES AND REFORMS ............................................208 2.1. The Communist Judicial Legacy............................................208 2.2. Judicial Reform and Economic Transition.............................213 2.3. Judicial Reform and Democratic Consolidation ....................217 3. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF JUDICIAL REFORM...................219 3.1. Models of Judicial Review .....................................................221 3.2. Systemic Effects on Democratization and Consolidation......223 3.3. Measuring Judicial Independence .........................................226 3.4 International and European Law ..........................................228 3.4.1. The Relationship Between International and Domestic Law.......................................................................228 3.4.2. The European Union and Council of Europe .............230 4. CASE STUDIES ..............................................................................233 4.1. Lithuania ...............................................................................234 4.1.1. Institutional and Contextual Factors..........................234 4.1.2. Case Law......................................................................236 4.1.2.1. The Death Penalty ..............................................236 4.1.2.2. Criminal Procedure