JSE 331 Online.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British College of Psychic Science

Quarterly Transactions of the British College of Psychic Science. Vol. I.—No. 4. January, 1923. EDITORIAL NOTES. With the present issue, Psychic Science completes its first year, and the thanks of its sponsors are cordially extended to all those whose sympathetic support has carried the under taking so successfully through a difficult period. * * * * * The aim and scope of our “ Quarterly” is now, wetrust, sufficiently well defined. The aim is essentially a constructive one, whilst analytic in the quest of truth ; its scope catholic, disdaining no form of enquiry and investigation which may bear upon the many obscure problems of spiritual interaction with Matter and physical life, through all the tenebrous avenues of the psychic regions as yet untraversed by Mind. * * * * * We shall endeavour, in the year to come, to give further and clearer effect to these purposes and thereby to assist the College towards a more definite realization of its destined sphere of usefulness ; that it may bring to birth in vigorous form the embryonic idea now forming in the public mind of the University of Psychic Science that is to be. It is at least legitimate to hope that the College may be the incubator of such an idea, and a foster-mother until it be fully fledged. The pages of Psychic Science will be open to correspondence and suggestions towards this end. 304 Quarterly Transactions B.C.P.S. For this must surely come to pass, and in that day we look to see the ministers of religion and the professors of science working together with united aim, the “ tabu ” of religious bigotry, on the one hand, and of intellectual arrogance on the other, being laid aside, and a fraternal understanding established for the great work of re-edification now to be done in the rearing of a new Temple of Humanity, in which truth shall be worshipped and intolerance and super stition shall have no place. -

The Vital Message

The Vital Message By Arthur Conan Doyle Classic Literature Collection World Public Library.org Title: The Vital Message Author: Arthur Conan Doyle Language: English Subject: Fiction, Literature, Children's literature Publisher: World Public Library Association Copyright © 2008, All Rights Reserved Worldwide by World Public Library, www.WorldLibrary.net World Public Library The World Public Library, www.WorldLibrary.net is an effort to preserve and disseminate classic works of literature, serials, bibliographies, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and other reference works in a number of languages and countries around the world. Our mission is to serve the public, aid students and educators by providing public access to the world's most complete collection of electronic books on-line as well as offer a variety of services and resources that support and strengthen the instructional programs of education, elementary through post baccalaureate studies. This file was produced as part of the "eBook Campaign" to promote literacy, accessibility, and enhanced reading. Authors, publishers, libraries and technologists unite to expand reading with eBooks. Support online literacy by becoming a member of the World Public Library, http://www.WorldLibrary.net/Join.htm. Copyright © 2008, All Rights Reserved Worldwide by World Public Library, www.WorldLibrary.net www.worldlibrary.net *This eBook has certain copyright implications you should read.* This book is copyrighted by the World Public Library. With permission copies may be distributed so long as such copies (1) are for your or others personal use only, and (2) are not distributed or used commercially. Prohibited distribution includes any service that offers this file for download or commercial distribution in any form, (See complete disclaimer http://WorldLibrary.net/Copyrights.html). -

Liquidation of the Ufo Investigators

CHAPTER 3 THE SPACE INTELLIGENCES SPEAK - TED OWENS – 1972 Suppose a man came to you and said that an earthquake would strike the California coast in a few days, and the very next day, a big earthquake on the California coast is reported in all the papers. Then the man comes to you again and says that in two weeks time, on Halloween, he will try to cause a UFO to be seen and reported in the newspapers. And sure enough, on Halloween night, a UFO is seen by numerous persons in Camden, N.J., headed for Philadelphia (where the man making these predictions then lived). It is written up in the newspapers, just as the man said it would be. The same man comes to you and says that in the days ahead, an early hurricane will appear off Florida. Five days later, a hurricane (Alma) appears, and hits Florida - the earliest hurricane in history to do so. When Hurricane Inez is born, this man comes to you and tells you that, contrary to what the Weather Bureau says, Inez will turn right at Cuba and go to the US. It does. Then, contrary to what the Weather Bureau says, the man says the hurricane will back up and take the same track Hurricane Betsy took last year, which Inez does. The man comes to you and says that in the near future, President Johnson will have a breakdown in health. Within 120 days, an unexpected public announcement is made that Johnson will need to have surgery. This same fellow then says that an attack on our warships in Vietnam is imminent. -

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

INDICE -.:: Biblioteca Virtual Espírita

INDICE A CIÊNCIA DO FUTURO......................................................................................................................................... 4 A CIÊNCIA E O ESPIRITISMO................................................................................................................................ 5 A PALAVRA DOS CIENTISTAS ..................................................................................................................... 6 UMA NOVA CIÊNCIA...................................................................................................................................... 7 O ESPIRITISMO ............................................................................................................................................. 8 O ESPIRITISMO E A METAPSÍQUICA........................................................................................................... 8 O ESPIRITISMO E PARAPSICOLOGIA ......................................................................................................... 9 A CIÊNCIA E O ESPÍRITO .................................................................................................................................... 10 A CIÊNCIA ESPÍRITA OU DO ESPÍRITO ............................................................................................................. 13 1. ALLAN KARDEC E A DEFINIÇÃO DO ESPIRITISMO, SOB O ASPECTO CIENTÍFICO......................... 14 2. A CIÊNCIA E SEUS MÉTODOS. ............................................................................................................. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

METEOR CSILLAGÁSZATI ÉVKÖNYV 2019 Meteor Csillagászati Évkönyv 2019

METEOR CSILLAGÁSZATI ÉVKÖNYV 2019 meteor csillagászati évkönyv 2019 Szerkesztette: Benkő József Mizser Attila Magyar Csillagászati Egyesület www.mcse.hu Budapest, 2018 Az évkönyv kalendárium részének összeállításában közreműködött: Tartalom Bagó Balázs Görgei Zoltán Kaposvári Zoltán Kiss Áron Keve Kovács József Bevezető ....................................................................................................... 7 Molnár Péter Sánta Gábor Kalendárium .............................................................................................. 13 Sárneczky Krisztián Szabadi Péter Cikkek Szabó Sándor Szőllősi Attila Zsoldos Endre: 100 éves a Nemzetközi Csillagászati Unió ........................191 Zsoldos Endre Maria Lugaro – Kereszturi Ákos: Elemkeletkezés a csillagokban.............. 203 Szabó Róbert: Az OGLE égboltfelmérés 25 éve ........................................218 A kalendárium csillagtérképei az Ursa Minor szoftverrel készültek. www.ursaminor.hu Beszámolók Mizser Attila: A Magyar Csillagászati Egyesület Szakmailag ellenőrizte: 2017. évi tevékenysége .........................................................................242 Szabados László Kiss László – Szabó Róbert: Az MTA CSFK Csillagászati Intézetének 2017. évi tevékenysége .........................................................................248 Petrovay Kristóf: Az ELTE Csillagászati Tanszékének működése 2017-ben ............................................................................ 262 Szabó M. Gyula: Az ELTE Gothard Asztrofi zikai Obszervatórium -

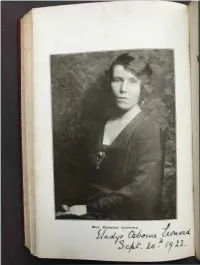

Psypioneer Journals

PSYPIONEER F JOURNAL Edited by Founded by Leslie Price Archived by Paul J. Gaunt Garth Willey EST Amalgamation of Societies Volume 9, No. —12:~§~— December 2013 —~§~— 354 – 1944- Mrs Duncan Criticised by Spiritualists – Compiled by Leslie Price 360 – Correction- Mrs Duncan and Mrs Dundas 361 – The Major Mowbray Mystery – Leslie Price 363 – The Spiritualist Community Again – Light 364 – The Golden Years of the Spiritualist Association – Geoffrey Murray 365 – Continued – “One Hundred Years of Spiritualism” – Roy Stemman 367 – The Human Double – Psychic Science 370 – Five Experiments with Miss Kate Goligher by Mr. S. G. Donaldson 377 – The Confession of Dr Crawford – Leslie Price 380 – Emma Hardinge Britten, Beethoven, and the Spirit Photographer William H Mumler – Emma Hardinge Britten 386 – Leslie’s seasonal Quiz 387 – Some books we have reviewed 388 – How to obtain this Journal by email ============================= Psypioneer would like to extend its best wishes to all its readers and contributors for the festive season and the coming New Year 353 1944 - MRS DUNCAN CRITICISED BY SPIRITUALISTS The prosecution of Mrs Duncan aroused general Spiritualist anger. But an editorial in the monthly LIGHT, published by the London Spiritualist Alliance, and edited by H.J.D. Murton, struck a very discordant note:1 The Case of Mrs. Duncan AT the Old Bailey, on Friday, March 31st, after a trial lasting seven days, Mrs. Helen Duncan, with three others, was convicted of conspiring to contravene Section 4 of the Witchcraft Act of 1735, and of pretending to exercise conjuration. There were also other charges of causing money to be paid by false pretences and creating a public mischief, but after finding the defendants guilty of the conspiracy the jury were discharged from giving verdicts on the other counts. -

I Identification and Characterization of Martian Acid-Sulfate Hydrothermal

Identification and Characterization of Martian Acid-Sulfate Hydrothermal Alteration: An Investigation of Instrumentation Techniques and Geochemical Processes Through Laboratory Experiments and Terrestrial Analog Studies by Sarah Rose Black B.A., State University of New York at Buffalo, 2004 M.S., State University of New York at Buffalo, 2006 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Geological Sciences 2018 i This thesis entitled: Identification and Characterization of Martian Acid-Sulfate Hydrothermal Alteration: An Investigation of Instrumentation Techniques and Geochemical Processes Through Laboratory Experiments and Terrestrial Analog Studies written by Sarah Rose Black has been approved for the Department of Geological Sciences ______________________________________ Dr. Brian M. Hynek ______________________________________ Dr. Alexis Templeton ______________________________________ Dr. Stephen Mojzsis ______________________________________ Dr. Thomas McCollom ______________________________________ Dr. Raina Gough Date: _________________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Black, Sarah Rose (Ph.D., Geological Sciences) Identification and Characterization of Martian Acid-Sulfate Hydrothermal Alteration: An Investigation -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

Essay Review: William Jackson Crawford on the Goligher Circle. the Reality of Psychic Phenomena

Journal of Scientifi c Exploration, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 529–539, 2013 0892-3310/13 ESSAY REVIEW William Jackson Crawford on the Goligher Circle The Reality of Psychic Phenomena: Raps, Levitations, Etc. by W. J. Crawford. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1918. 246 pp. (hardcover). $24.99 (paperback by Ulan Press, 268 pp., ASIN B0087KDU4I). Hints and Observations for Those Investigating the Phenomena of Spiritualism by W. J. Crawford. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1918. 110 pp. (hardcover). $19.75 (paperback by Nabu Press, 126 pp., ISBN 978- 1171753643). Experiments in Psychical Science: Levitation, Contact, and the Direct Voice by W. J. Crawford. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1919. 201 pp. (hardcover). $23.99 (paperback by Ulan Press, 214 pp., ASIN B00B3DED4C). The Psychic Structures at the Goligher Circle by W. J. Crawford. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1921. 176 pp. (hardcover). $8.58 (paperback by Forgotten Books, 216 pp., ASIN B0087KDU4I). The page references cited are preceded by the abbreviated book title: Reality, Hints, Experiments, or Structures. In 1914, Dr. William J. Crawford, a lecturer in mechanical engineering at Queen’s University of Belfast, Ireland, began investigating the mediumship of 16-year-old Kathleen Goligher. The phenomena surrounding the young girl included communicating raps, automatic writing, trance voice, fl oating objects, and table levitations. In all, Crawford had 87 sittings over some two-and-a-half years with the Goligher Circle. His fi rst, third, and fourth books, as listed above, deal solely with the Goligher phenomena, while the second-listed book is very general and includes observations with other mediums. -

Secret FBI CIA NSA Pentagon KGB Navy Army War

secret FBI CIA NSA Pentagon KGB navy army war please allow some time for the page to load ufo alien secrets cosmic conflict 01 Page ("COSMIC CONFLICT", Vol. 2, Edition 1.2) 01 PAGE NO. 01 Cosmic Conflict & The Da'Ath Wars Page 02 "And the Lord said unto the Serpent... I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed..." -- Genesis ch. 3, vs. 14-15 Page 03 The title of this work will be fully understood as the reader studies the files contained herein. Page Aviation & Simulation 04 Books & CDs The following files, originally appearing in printed form and later transcribed to Daily Forum the present format, are an attempt to tie-together various unanswered Page Environment questions relating to Christian theology, prophecy, cult research, science, 05 Financial News vanguard technology, phenomenology, Einsteinean theory, electromagnetism, aerospace technology, modern and pre history, myth-tradition and legend, Page Galaxy News antediluvian societies, ancient artifacts, cryptozoology, biology and genetic 06 Horoscopes sciences, computer sciences, Ufology, Fortean research, parapsychology, Human Rights conspiraology, missing persons research, human and animal mutilations, Page Japan & Neighbours anthropology, parapolitical sciences, international economics, secret societies, 07 Just Style demonology, advanced astronomy, assassinations, psychic and mental Mind Spirit manipulation or control, international conflict, et al and attempts to bring the Page Quotes of the Day mysteries surrounding these subjects together in a workable and documentable 08 scenario. Religion Page Russia News Many of the sources for these Files include a loose network of hundreds of Science News researchers who have pooled their corroborative information and resources in 09 Search & Directory order to put together the "Grand Scenario" as it is outlined in the Files.