The Apocalyptic Aspect of St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Christian Martyr Movement of 850S Córdoba Has Received Considerable Scholarly Attention Over the Decades, Yet the Movement Has Often Been Seen As Anomalous

The Christian martyr movement of 850s Córdoba has received considerable scholarly attention over the decades, yet the movement has often been seen as anomalous. The martyrs’ apologists were responsible for a huge spike in evidence, but analysis of their work has shown that they likely represented a minority “rigorist” position within the Christian community and reacted against the increasing accommodation of many Mozarabic Christians to the realities of Muslim rule. This article seeks to place the apologists, and therefore the martyrs, in a longer-term perspective by demonstrating that martyr memories were cultivated in the city and surrounding region throughout late antiquity, from at least the late fourth century. The Cordoban apologists made active use of this tradition in their presentation of the events of the mid-ninth century. The article closes by suggesting that the martyr movement of the 850s drew strength from churches dedicated to earlier martyrs from the city and that the memories of the martyrs of the mid-ninth century were used to reinforce communal bonds at Córdoba and beyond in the following years. Memories and memorials of martyrdom were thus powerful means of forging connections across time and space in early medieval Iberia. Keywords Hagiography / Iberia, Martyrdom, Mozarabs – hagiography, Violence, Apologetics, Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain – martyrs, Eulogius of Córdoba, martyr, Álvaro de Córdoba, Paulo, author, Visigoths (Iberian kingdom) – hagiography In the year 549, Agila (d. 554), king of the Visigoths, took it upon himself to bring the city of Córdoba under his power. The expedition appears to have been an utter disaster and its failure was attributed by Isidore of Seville (d. -

St. Catherine of Siena Roman Catholic Church

ST. CATHERINE OF SIENA ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH ESTABLISHED 1964 3450 Tennessee Street, Vallejo, California 94591 PARISH OFFICE HOURS Monday through Thursday ~ 11:00am to 4:00pm Friday ~ 9:00am to 12:00pm Telephone | (707) 553-1355 ||| Email | [email protected] WELCOME! Website | stcatherinevallejo.org ||| Social Media | facebook.com stcatherinevallejo HOLY MASSES 11TH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME ~ SUNDAY, JUNE 13, 2021 DAILY MASSES 7:45AM, 6:00 PM SATURDAY MASSES 8:00AM 5:00PM Anticipated Mass for Sunday SUNDAY MASSES 8:00AM 10:00AM | Livestreamed YouTube 12:00PM, 3:00 PM - Español 5:00PM Please check our website for any Mass updates. www.stcatherinevallejo.org Or MyParish app PASTORAL STAFF PASTOR Fr. Glenn Jaron, MSP PAROCHIAL VICAR Fr. Jose “Peping” Estaniel, MSP PERMANENT DEACONS Rudy David Pete Lobo Alejandro Madero Juan Moreno Bobby Peregrino Dennis Purificacion St. Catherine of Siena, Vallejo cell phone and minor children to bathrooms while at mass. PARISH STAFF 707-553-1355 Secretaries Sarah Macaraeg Reanah Manalansan EUCHARISTIC ADORATION Bookkeeper The church is open for private personal prayer only. Mike Reay WEDNESDAYS & FIRST FRIDAYS After 7:45AM Morning Mass To Before 6:00PM Evening Mass Custodian THIRD FRIDAYS for Holy Vocations Rudy Caoili St. Romuald of Ravenna, Rectory Housekeeper Feast Day Saturday, June 19 Marissa Madrinan Landscape Maintenance After witnessing with horror his father kill a relative in a duel, Mark Besta Romuald retired to the Monastery of St. Apollinaris near Ra- venna, where he later served as ab- PARISH SCHOOL bot. He went to Catalonia, Spain, 707-643-6691 and seems to have been impressed Christine Walsh, Principal by the vigorous life in the monaster- 3460 Tennessee Street ies. -

Assumption Church for the Celebration of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass According to the Traditional Latin “Extraordinary” Form

* * * CELEBRANT : The Reverend Peter Hrytsyk * WELCOME to Historic Our Lady of the Assumption Church for the celebration of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass according to the Traditional Latin “Extraordinary” Form. Join us as we render glory to God according to Holy Mother Church’s historic liturgy, employing her rich treasury of sacred music. The Tridentine Mass is celebrated here at Assumption every Sunday at 2:00 PM and every Tuesday at 7:00 PM. TODAY ’S MASS INTENTION : For Daphne Witty ST. ROMUALD : After entering the monastery of St. Apollinaris in Ravenna, Italy around the year 970 A.D., St. Romuald went on to found the Camaldolese order of hermits. Members observed a strict rule with perpetual fasting; St. Romuald never used a bed and became known as a model ascetic. He was known for bringing people of privilege back to God. A quote attributed to St. Romuald: “Better to pray one psalm with devotion and compunction than a hundred with distraction.” RED LATIN /E NGLISH MISSALS ARE AVAILABLE FOR SALE after Mass at the missal table at the back of the church for $6.00 each. These missals can help familiarize yourself, family, and friends with the Traditional Latin Mass. ASSUMPTION CHURCH 350 Huron Church Road Windsor, Ontario N9C 2J9 (519) 734-1335 / (248) 250-2740 www.windsorlatinmass.org February 7, 2012 7:00 P.M. ST. ROMUALD, ABBOT * * * The organ will accompany the Entrance Procession. INTROIT Psalm 36. 30, 31 Os justi meditábitur sapiéntiam, et lingua ejus The mouth of the just shall meditate wisdom, and his tongue loquétur judícium: lex Dei ejus in corde ipsíus. -

Bulletin-June-2-2019

SEVENTH SUNDAY OF EASTER Mass Intentions For Your Information Sanctuary Lamp Saturday, June 1 This week’s sanctuary lamp at St. Francis Church burns in 4:30pm memory of Rosemary Flynn Walsh. Sunday, June 2 8:00am†Rosemary Walsh Requested by Kathleen & Jeff Carney All are welcome to attend a Mass at noon 10:00am †Richard De Joseph on Wednesday, June 19th at our St. (4th Anniversary Remembrance) Requested by Family Romuald Chapel on Atlantic Ave. in 12:00nn †Dolores Ramirez Matunuck to celebrate the Memorial of Requested by Family St. Romuald, abbot and hermit, the found- Monday, June 3 er of the Camaldolese Benedictines, who 7:00am †Msgr. Cornelius J. Holland (5th Pastor) died on June 19, 1027. Light refresh- 63rd Anniversary Remembrance ments will follow. Tuesday, June 4 7:00am †Concetta Wilson Requested by Michele Nielsen Thursday, June 6 7:00am Mass for the People Catholic Communication Campaign Friday, June 7 Second Collection: Weekend of June 8/9 7:00am †Rita & Tom O’Rourke & Warren Next week, our second collection is for the Catholic Behie Communication Campaign. This campaign connects people Requested by Family Saturday, June 8 with Christ in the United States and in developing countries 4:30pm †William & Teresa Bodah around the world through the Internet, television, radio, and print Requested by Family media. Fully 50% of funds collected remain here in the Diocese Sunday, June 9 of Providence to fund local communications efforts. Your 8:00am†Jean Krul (Anniversary Remembrance) support helps spread the Gospel message! Requested by Family 10:00am To learn more, visit www.usccb.org/ccc. -

Shadow Kingdom: Lotharingia and the Frankish World, C.850-C.1050 1. Introduction Like Any Family, the Carolingian Dynasty Which

1 Shadow Kingdom: Lotharingia and the Frankish World, c.850-c.1050 1. Introduction Like any family, the Carolingian dynasty which ruled continental Western Europe from the mid-eighth century until the end of the ninth had its black sheep. Lothar II (855-69) was perhaps the most tragic example. A great-grandson of the famous emperor Charlemagne, he belonged to a populous generation of the family which ruled the Frankish empire after it was divided into three kingdoms – east, west and middle – by the Treaty of Verdun in 843. In 855 Lothar inherited the northern third of the Middle Kingdom, roughly comprising territories between the Meuse and the Rhine, and seemed well placed to establish himself as a father to the next generation of Carolingians. But his line was not to prosper. Early in his reign he had married a noblewoman called Theutberga in order to make an alliance with her family, but a few childless years later attempted to divorce her in order to marry a former lover called Waldrada by whom he already had a son. This was to be Lothar’s downfall, as his uncles Charles the Bald and Louis the German, kings respectively of west and east Francia, enlisted the help of Pope Nicholas I in order to keep him married and childless, and thus render his kingdom vulnerable to their ambitions. In this they were ultimately successful – by the time he died in 869, aged only 34, Lothar’s divorce had become a full-blown imperial drama played out through an exhausting cycle of litigation and posturing which dominated Frankish politics throughout the 860s.1 In the absence of a legitimate heir to take it over, his kingdom was divided between those of his uncles – and with the exception of a short period in the 890s, it never truly existed again as an independent kingdom. -

The Scenography of Power in Al-Andalus and the ʿabbasid

Medieval Medieval Encounters 24 (2018) 390–434 Jewish, Christian and Muslim Culture Encounters in Confluence and Dialogue brill.com/me The Scenography of Power in Al-Andalus and the ʿAbbasid and Byzantine Ceremonials: Christian Ambassadorial Receptions in the Court of Cordoba in a Comparative Perspective Elsa Cardoso Researcher of the Centre for History, University of Lisbon Faculty of Arts of the University of Lisbon, Alameda da Universidade 1600 Lisbon, Portugal [email protected] Abstract This essay considers ceremonial features represented during Christian diplomatic re- ceptions held at the court of Cordoba, under the rule of Caliphs ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III (912‒961) and al-Ḥakam II (961‒976), in a comparative perspective. The declaration of the Umayyad Caliphate of the West by ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III marked the institution- alization of a carefully elaborated court ceremonial, reaching its greatest develop- ment under the rule of al-Ḥakam II. Detailed official ambassadorial ceremonies will be addressed, such as receptions of ambassadors from Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos, and King Otto I, or the reception and submission of Ordoño IV, deposed king of Leon, accounted by both Muslim and Christian sources. Such cer- emonies will be compared with ʿAbbasid and Byzantine similar receptions, analyzing furthermore the origin and symbology of those rituals within the framework of diplo- matic and cultural exchanges and encounters. Keywords Al-Andalus ‒ Umayyads of Cordoba ‒ ceremonial ‒ diplomacy ‒ Madīna al-Zahrāʾ ‒ ʿAbbasids ‒ Byzantium -

Fra Angelico Wor's of Fra Angelico

’ “ l Be l s M ini ature Series Of Paint ers . E i d tt D . t d b . C . I IAM Li . e y G W LL SON, Pot' 00 w ill: ll a t 8 , 8 I ustr tions , clotlz , I s . ne . V LA' '. B G . W L L MSO Litt. D . E 'U E y C . I IA N , - S IR E . RNE NE B M LCOLM ELL . BU JO S . y A B F R AN ELI B . I L IAMSON Litt . D . A G CO. y G . C W L , ‘ F W TT R EM . A S . A . B . T T N G . , y c BA A R M ' R L E LEEVE . GEORGE O NE . By o w y C W T E AND HI P P B DGC M BE A T AU S U ILS . y E U T S AL E', B . A. OTH ERS TO FOLLOW . D : B LON ON GEORGE ELL SONS, 'OR' STREET OVENT ARDEN , C G . ' ’ l r . ' [Perugz a Gal e y A lz m z rz fl wto j L H E M AD ONNA A N D C H I D . ’ Bell s M iniat ure Seri es Of Pai nters F RA ANG E L ICO LL M I W A L TT. D G G C . I I S EO R E O N , . N LONDON GEO RGE BE L L SONEJ 1 90 1 TABL E O F CO NTENTS CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE LIFE O F FRA ANGELICO WOR'S OF FRA ANGELICO SAN MARCO THE ART O F FRA ANGELICO OU R ILLUSTRATI ONS CHIEF WOR'S B' THE ARTIST SUGGESTED CHRONOLOG' OF THE WOR'S CHIEF BOO'S ON FRA ANGELICO L IS T OF IL LU STRATIO NS PAGE THE MADONNA AND CHILD THE DANCE OF THE AN GELS ’ a F o Aeeaden n , l rence RIST As A PI LGRIM San M areo Florenee CH , THE TRANSFIGURATION an arco F lore e S M , nc E IRST C ARIST S an M arco F lo rence TH F EU H , THE ANNUNCIATION E R CI FI X IO N S an M arco Florence TH C U , SAN LOREN'O D ISTRI BUTING ALM S Tlee R om e C HRO N OLOG I CAL TABLE 1 8 . -

Diplomacy Between Emperors and Caliphs in the Tenth Century

86 »The messenger is the place of a man’s judgment«: Diplomacy between Emperors and Caliphs in the Tenth Century Courtney Luckhardt* Travel and communication in the early medieval period were fundamental parts of people’s conceptions about temporal and spiritual power, which in turn demonstrated a ruler’s legit imacy. Examining the role of messengers and diplomatic envoys between the first Umayyad caliph of alAndalus, ‘Abd alRahman III, and his fellow tenthcentury rulers in Christian kingdoms, including the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos and the first Holy Roman emperor, Otto I, illuminates internal and external negotiations that defined the pluralistic Iberian society in the early Middle Ages. Formal religious and ethnic differences among Muslim rulers and nonMuslim messengers enhanced the articulation of political le gitimacy by the caliph. Diplomatic correspondence with foreign rulers using the multiplicity of talents and ethnoreligious identities of their subjects was part of the social order provided by the Andalusi rulers and produced by those they ruled, demonstrating the political autho rity of the Umayyad caliphate. Keywords: diplomacy, messengers, al-Andalus, political authority, ‘Abd al-Rahman III, Muslim- Christian relations »The wise sages have said… the messenger is the place of a man’s judgment, and his letter is the place of his intellect.« So related Ibn alFarra’ in the Rasul al-muluk, a treatise on diplomacy commissioned by the caliph of alAndalus in the second half of the tenth century.1 Political and diplomatic connections between elite groups and protostates happened at the personal and individual level in the early medieval period. -

Camaldolese Tidings

Camaldolese Hermits of America Camaldolese Tidings New Camaldoli Hermitage • Big Sur, California • Volume 19 • Issue 1 • Fall 2013 Installation of a New Prior “The spiritual life for Jesus was––and I suppose the ideal of the spiritual life for us could be–– like breathing in and breathing out, as simple as that. Breathing in the love of God, breathing out the love of God. Breathing in strength, breathing out compassion. Breathing in the fire, breathing out justice.” – From Fr. Cyprian’s installation homily Prior Cyprian Consiglio, OSB Cam. 2 ~ Camaldolese Tidings The men of the community: Fr. Daniel, Bro. Joshua, Fr. Isaiah, Fr. Bruno, Bro. Emmanuel, Fr. Thomas, Fr. Raniero, Fr. Mario (Visita- tor from Fonte Avellana, Italy), Don Alessandro (Prior General from Camaldoli), Fr. Zacchaeus, Fr. Cyprian, Bishop Richard Garcia of the Diocese of Monterey, Fr. Andrew, Fr. Arthur, Bro. Bede, Fr. Robert. Fr. Michael, Bro. Ignatius, Bro. Gabriel, Bro. Ivan, Bro. James, Bro. Michael, Bro. Benedict, and Bro. Isaac. Dear Oblates and Friends, New Camaldoli in 1992, and offered his We monks, and so many others know monastic vows in 1994, I myself happily our dear brother and friend Cyprian to It is my receiving them as Prior. He then studied be a man of deep faith, profound prayer, pleasure, and for the priesthood at St. John Seminary, in real wisdom, and wonderful compassion. that of the whole Camarillo, California, writing his Masters In his heart he is seeking what we are community, to thesis on the ancient, biblical and monastic all seeking ultimately, ever deeper union introduce to you understanding of humanity as constituted with God and, in God, with all of human- our new Prior, by three interrelated and complementary ity, with all of creation. -

Al-Andalus -- an Andalucian Romance

June 29, 20181 Al-Andalus -- An Andalucian Romance A script by Marvin Wexler 30 The Esplanade New Rochelle, NY 10804 (914) 632-8110 [email protected] 1 Also available at www.andalucianromance.org and www.poetryfortheelderly.org. An earlier version appeared on that website on December 2, 2016. DM1\8800968.1 A script by Marvin Wexler 30 The Esplanade New Rochelle, NY 10804 (914) 632-8110 [email protected] Al-Andalus -- An Andalucian Romance This is an historical romance about the culture of Covivéncia in 10th Century Muslim- ruled al-Andalus, a/k/a Southern Spain. It takes place mainly in Córdoba, the capital of al- Andalus, with a few scenes in 10th Century Barcelona, one scene at the Roman ruins in Tarragona (west of Barcelona) and a few opening scenes in the Tabernas Desert, at nearby Cabo de Gata and in the countryside in Almería (all of which are on or near the coastal road to Tarragona). The principal theme is the historical reality of intimate and constructive relations between Muslims, Jews and Christians in al-Andalus at that time. What they shared was a culture – a culture that placed high value on, among other things, learning, on beauty, and on what today we might call moral character development. Other themes include: -- The beginnings of the Renaissance in Europe, in a Western European land under Muslim rule. -- The power of poetry, including Arabic poetry, and the development of Hebrew poetry through Arabic poetry. -- The importance, both personally and for faith systems, of both engaging The Other and looking within. -

Cécile Caby Faire Du Monde Un Ermitage: Pietro Orseolo, Doge Et Ermite* [In Corso Di Stampa in Guerriers Et Moines

Cécile Caby Faire du monde un ermitage: Pietro Orseolo, doge et ermite* [In corso di stampa in Guerriers et moines. Conversion et sainteté aristocratiques dans l'Occident médiéval (IX e-XIIe siècle) (Collection du Centre d'Études médiévales, 4), a cura di M. Lauwers, Nice 2002 © dell'autrice - Distribuito in formato digitale da "Reti Medievali"] Longum preterea nominatim exequi quot quam claros Cristo servos sibi discipulos ambiendo [Romualdus] quesierit, in quibus et duces et comites et filii comitum fuerunt, quin et ipse romanus imperator Otto (Pétrarque, De Vita solitaria, II, viii) Si le culte de Pietro Orseolo n'eut qu'un rayonnement limité, son dossier hagiographique et biographique est en revanche exceptionnellement riche en raison de la place occupée à Venise par le doge converti au monastère et sa famille, de sa rencontre sur la voie de la conversion avec un personnage phare des mouvements réformateurs de l'An Mil, Romuald de Ravenne, et enfin de la révérence dont il fut entouré dans son monastère de retraite (Saint-Michel de Cuxa) dans les années qui suivirent sa mort, années qui coïncident avec l'abbatiat d'Oliba à Cuxa et Ripoll. Compte tenu de la complexité des sources, il faut pour commencer en démêler l'écheveau avant de parcourir les principaux épisodes de la conversion de Pietro Orseolo et de ses compagnons1, de façon à pouvoir, dans un dernier temps, cerner, à travers cette expérience singulière, un modèle élitiste de sainteté et de conversion laïque, ou plutôt, comme nous le verrons, un modèle participant d'une cascade de conversions de grands laïcs permettant de repérer dans l'entourage de Pietro Orseolo la mise en pratique, en partant du sommet de la société, de l'idéal de transformation du monde en un ermitage attribué par le jeune Pierre Damien à Romuald de Ravenne. -

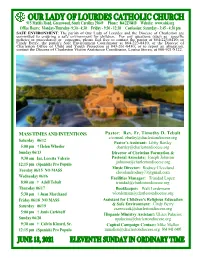

June 13, 2021

MASS TIMES AND INTENTIONS St. Romuald, Abbot - Feast day: Saturday, June 19 Saint Romuald, who founded the Camaldolese monastic order during the early eleventh century, has his liturgical memorial on June 19. Working within the Western Church’s Benedictine tradition, he revived the primitive monastic practice of hermit life, allowing for greater solitude in a communal setting. Born into an aristocratic family during the middle of the tenth century, Romuald grew up in a luxurious and worldly environment, where he learned little in the way of self-restraint or religious devotion. Yet he also felt an unusual attraction toward the simplicity of monastic life, prompted by the beauty of nature and the experience of solitude . It was not beauty or tranquility, but a shocking tragedy that spurred him to act on this desire. When Romuald was 20 years old, he saw his father Sergius kill one of his relatives in a dispute over some property. Disgusted by the crime he had witnessed, the young man went to the Monastery of St. Apollinaris to do 40 days of penance for his father. These 40 days confirmed Romuald’s monastic calling, as they became the foundation for an entire life of penance. ...He left the area near Ravenna and went to Venice, where he became the disciple of the hermit Marinus. Both men went on to encourage the monastic vocation of Peter Urseolus, a Venetian political leader who would later be canonized as a saint. When Peter joined a French Benedictine monastery, Romuald followed him and lived for five years in a nearby hermitage.