Choquequirao, Topa Inca's Machu Picchu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who We Are? - MACHUPICCHU TERRA S.R.L

Who We Are? - MACHUPICCHU TERRA S.R.L INCA TRAIL MACHU PICCHU is a brand MACHUPICCHU TERRA, Travel Agency and Tour Operator authorized to sell Inca Trail Machu Picchu. Our company is located in Cusco, the capital of the Inca Empire and the Tourist Capital of South America. We created this web site considering that availability for the Inca Trail Machu Picchu is quickly exhausted; since it is limited to only 500 people per day (including support staff porters, chefs, guides, etc.) making it extremely necessary booking several months in advance; at least 6 months in advance. MACHU PICCHU TERRA, feels proud to provide superior service to all our customers, and we manage all services necessary to operate and organize all the packages offered, cars, minibuses, equipment, office-qualified staff, specialized assistants and guides professionals. Whether you are looking for a trip to Peru that includes a hike to Machu Picchu or just a relaxing family vacation, it is our mission to MACHUPICCHU TERRA work with you to create your trip to Peru. We welcome all types of customers with special travel interests, economic and Premium. Our ex cellent service always searches at any time and satisfy all customers throughout Peru. All MACHUPICCHU TERRA packages have been prepared by our travel consultants with experience and knowledge, our company MACHUPICCHU TERRA is based on 4 different categories of hotels: Basic Class, based on 2 stars hotels. Premium Class, based on 4 stars hotels. Economy Class, based on 3 stars hotels. VIPs Class, based on 5 stars hotels. Legitimacy of Inca Trail Machu Picchu MACHU PICCHU TERRA is an Authorized Agency by the Ministry of Culture, the assigned code is: MA0473, responsible and efficient company willing to provide the best service. -

Generated with Expertpdf Html to Pdf Converter

ARTS & CULTURE Jul 20, 2017 Sacred Valley, Peru: How to Plan the Perfect Trip SARAH SCHLICHTER Exploring Peru’s Sacred Valley of the Incas feels Save This Story like going back in time. Centuries-old Inca terraces spill down green, misty hillsides. Women in traditional Andean dress stroll along the cobblestone streets of colonial towns, long black braids trailing down their backs. Colorful village markets display soft alpaca sweaters, hats, and ponchos woven by hand. The Sacred Valley is tucked between Cusco and Machu Picchu, running along the Urubamba River from Pisac to Ollantaytambo. Travelers with limited time often skip the Sacred Valley in their rush to see Machu Picchu, but the valley’s picturesque towns and well-preserved Inca ruins are worth a day or two in their own right. The Sacred Valley has an additional benefit for travelers hoping to acclimate to the region’s altitude before visiting Machu Picchu: Most of the valley sits several hundred feet lower than Cusco. When to Visit the Sacred Valley For the best chance of dry weather, visit the Sacred Valley during its high season between June and August. The rainiest part of the year is November through March. Come during the shoulder-season months—April, May, September, and October —for slightly smaller crowds and lower prices than you’d find in high season, without an excessive threat of rain. Top Sights in the Sacred Valley Pisac: Famous for its Sunday market, in which farmers come from all over the Sacred Valley with a colorful bounty of local fruit and vegetables, Pisac is also worth a visit for its large Inca ruins. -

Inca-Trail-Choquequirao-8-Days.Pdf

Who We Are? - MACHUPICCHU TERRA S.R.L INCA TRAIL MACHU PICCHU is a brand MACHUPICCHU TERRA, Travel Agency and Tour Operator authorized to sell Inca Trail Machu Picchu. Our company is located in Cusco, the capital of the Inca Empire and the Tourist Capital of South America. We created this web site considering that availability for the Inca Trail Machu Picchu is quickly exhausted; since it is limited to only 500 people per day (including support staff porters, chefs, guides, etc.) making it extremely necessary booking several months in advance; at least 6 months in advance. MACHU PICCHU TERRA, feels proud to provide superior service to all our customers, and we manage all services necessary to operate and organize all the packages offered, cars, minibuses, equipment, office-qualified staff, specialized assistants and guides professionals. Whether you are looking for a trip to Peru that includes a hike to Machu Picchu or just a relaxing family vacation, it is our mission to MACHUPICCHU TERRA work with you to create your trip to Peru. We welcome all types of customers with special travel interests, economic and Premium. Our ex cellent service always searches at any time and satisfy all customers throughout Peru. All MACHUPICCHU TERRA packages have been prepared by our travel consultants with experience and knowledge, our company MACHUPICCHU TERRA is based on 4 different categories of hotels: Basic Class, based on 2 stars hotels. Premium Class, based on 4 stars hotels. Economy Class, based on 3 stars hotels. VIPs Class, based on 5 stars hotels. Legitimacy of Inca Trail Machu Picchu MACHU PICCHU TERRA is an Authorized Agency by the Ministry of Culture, the assigned code is: MA0473, responsible and efficient company willing to provide the best service. -

Machu Picchu Was Rediscovered by MACHU PICCHU Hiram Bingham in 1911

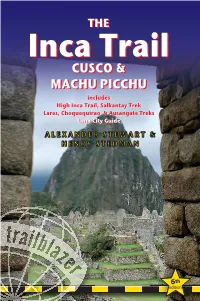

Inca-6 Back Cover-Q8__- 22/9/17 10:13 AM Page 1 TRAILBLAZER Inca Trail High Inca Trail, Salkantay, Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks + Lima Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks Salkantay, High Inca Trail, THETHE 6 EDN ‘...the Trailblazer series stands head, shoulders, waist and ankles above the rest. Inca Trail They are particularly strong on mapping...’ Inca Trail THE SUNDAY TIMES CUSCOCUSCO && Lost to the jungle for centuries, the Inca city of Machu Picchu was rediscovered by MACHU PICCHU Hiram Bingham in 1911. It’s now probably MACHU PICCHU the most famous sight in South America – includesincludes and justifiably so. Perched high above the river on a knife-edge ridge, the ruins are High Inca Trail, Salkantay Trek Cusco & Machu Picchu truly spectacular. The best way to reach Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks them is on foot, following parts of the original paved Inca Trail over passes of Lima City Guide 4200m (13,500ft). © Henry Stedman ❏ Choosing and booking a trek – When Includes hiking options from ALEXANDER STEWART & to go; recommended agencies in Peru and two days to three weeks with abroad; porters, arrieros and guides 35 detailed hiking maps HENRY STEDMAN showing walking times, camp- ❏ Peru background – history, people, ing places & points of interest: food, festivals, flora & fauna ● Classic Inca Trail ● High Inca Trail ❏ – a reading of The Imperial Landscape ● Salkantay Trek Inca history in the Sacred Valley, by ● Choquequirao Trek explorer and historian, Hugh Thomson Plus – new for this edition: ❏ Lima & Cusco – hotels, -

Download Collection

1 Index Cusco Choquequirao “Cradle of Gold” | 5D 4N 4 Horse Riding | Half Day 8 Inca Trail to Machu Picchu | 4D 3N 12 River Rafting | Half Day 16 Salkantay Trek | 5D - 4N 20 Short Inca Trail | 2D - 1N 24 Via Ferrata | Half Day 28 Zip Line | Half Day 32 Iquitos Fishing | Half Day 36 PAracas Buggies & Sandboard | Half Day 40 Desert Adventure | Half Day 44 Puno Adventure Collection Biking in the Titicaca Valley | Half Day 48 A Kayaking | Full Day 52 Quad Biking around Titicaca Valley | Half Day 56 Tumbes or Piura Kitesurfing | Half Day 60 Marine Life Tour | Half Day 64 Surfing | Half Day 68 2 3 Day 1: Cusco - Limatambo - Carhuasi - Huanipaca - Tambobamba Day 2: Tambopata - San Ignacio - Cusco Choquequirao Day 3: Choquequirao Choquequirao Exploring Cusco Day 4: Choquequirao - Marampata - Cradle of Gold Santa Rosa - Playa Rosa Linda Day 5: Playa Rosa Linda - Chiquisca - Cachora - Cusco 4 5 Choquequirao Trek | 5D - 4N Choquequirao in Quechua means “Golden Cradle”, although this is probably not its original name, this mysterious and dazzling place is another “Lost city of the Incas” located high on a ridge spur, almost 1750m above the raging glacier-fed Apurimac River and surrounded by towering snow- capped peaks of the Vilcabamba mountain range. Enjoy a great experience and a new discovery, appreciate the magnificence of Choquequirao with its palaces, temples, two-tier fountain systems, canals, aqueducts, and its lovely terraces “upholstered” with profuse vegetation. 6 7 Moray is an archaeological site in Peru approximately 50 km (31 mi) northwest of Cuzco on a high Cusco plateau at about 3500 m (11,500 ft) and just west of the village of Maras. -

INTERIORES INCA INGLES CORREGIDO 2016.Indd

JULY 2016 ISSUE 1 A MAGICAL TRIP THROUGH THE IMPERIAL CITY OF CUSCO TOURING THE HIGHEST NAVIGABLE LAKE IN THE WORLD THE WHITE CITY AND ITS VOLCANOES THE MOST GIGANTIC ON THE PLANET 1/ “I do not believe that civilizations have to die because civilization is not an organism. It is a product of wills.” Arnold Joseph Toynbee. 2 / INCA TRAIL Torre Tagle Palace. EDITORIAL Peru possesses a cultural wealth of exceptional value. For millennia Additionally, new market niches have been developed, such as bird now, our territory has been home to the most important historical watching; thermal baths; medical tourism; and the culinary tourism development processes of humankind. The prestigious British that is being consolidated through the organization of the Mistura historian Arnold Toynbee named Peru one of the eight “cradles of international culinary fair. This effort has become a common thread world civilization” and highlighted the abundance and originality of that runs through the entire Peruvian State, projecting us abroad its contributions to the planet’s cultural heritage. with an immense potential from three different perspectives: as a commercial product; as a structure for the promotion of tourism; Behind the magnificence of Machu Picchu, the mystery of the and from a cultural point of view. Nazca Lines, the refinement of the Lord of Sipán, the symbolic force of the Temple of Chavín, and the primordial fire of the city of Caral All these efforts have generated a kind of tourism revolution in Peru, lie 5,000 years of civilization; few peoples in the world can boast of which received 3.5 million foreign tourists in 2015 and in September such privilege. -

TURN RIGHT at MACHU PICCHU

Linga-Bibliothek Linga A/907331 TURN RIGHT at MACHU PICCHU REDISCOVERING THE LOST CITY ONE STEP AT A TIME MARK ADAMS DUTTON It- • Index Abancay, Peru, 37, 39 Amazonas Explorer, 42, 43, 232 Abril, Emilio, 262 American Board of Commissioners for Abril, Roxana, 262-63, 290 Foreign Missions, 15 Across South America (Bingham), The American Mercury, 249 33-34, 49 American Museum of Natural Adams, Alex, 9, 24, 36 History, 204 Adams, Aurita, 19, 20, 24, 47 Amundsen, Roald, 78-79, 80,113, 215 Adams, Lucas, 24 Andean spectacled bears, 171-72 Adams, Magnus, 24, 289 Andenes (terraces), 120 Adventure, 25, 54 Angkor Wat, 188 Age of Discovery, 67 Angrand, Leonce, 57 agriculture* animal sacrifice, 61,121 Bingham on, 132 anthropology, 205, 219 and celestial orientation of Inca sites, Antis, 116, 126 221-22 Antisuyo, 61, 116, 117 and climate theories, 186n Antisuyo (Savoy), 157 and the hacienda system, 113-14 Aobama River, 171, 220 and land reforms, 114 Aobama Valley, 277 and Machu Picchu, 187 apachetas, 92, 93 and terrace structures, 58, 61, Apurimac River, 37, 38, 52, 93, 128 177-78, 192 apus Aguas Calientes, 7, 169, 172, 174-75, at Choquequirao, 58-59 182, 192, 197, 240 at Choquetacarpo Pass, 92-93 Ales Hrdlicka, 205 and the Ice Maiden, 219 Almaro, Diego de, 130 and the Inca Trail, 272-73, 274 alpacas, 61 and location of Inca sites, 62 altitude sickness, 46, 82, 90, 92, 153 at Machu Picchu, 193 Alvistur, Tomas, 206, 236 and Machu Picchu theories, 279 320 Index opus (cont.) and antiquities dealing, 245 most revered peaks, 220 and artifacts controversy, -

Trek to the Lost City of Choquequirao

Trek to the Lost City of Choquequirao 8 Days Trek to the Lost City of Choquequirao Combine two epic trails to two different "lost cities" — the iconic Machu Picchu, and its lesser-known counterpart, Choquequirao — for one incredible Peru journey. The trip begins with a trek to Choquequirao, once a major cultural and religious center for the Incas. These remote ruins enjoy a breathtaking location high in the mountains above the roaring Apurimac River. Then, hike the last leg of the Inca Trail to explore the spectacular stone citadel of Machu Picchu. Your journey is book-ended by stays in beautiful Cusco, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Details Testimonials Arrive: Cusco, Peru “We have traveled throughout the world, but never experienced a level of service and attention to detail Depart: Cusco, Peru as we did with MT Sobek.“ Dennis G. Duration: 8 Days Group Size: 4-14 Guests “Traveling with MT Sobek is like gaining a new set of close friends that have shared an incredible Minimum Age: 16 Years Old experience together.” Mark N. Activity Level: . REASON #01 REASON #02 REASON #03 MT Sobek has been designing Follow expert local guides on heart- This trip has been carefully crafted pioneering trekking pumping hikes amid breathtaking to visit not one but two iconic Inca adventures in the Sacred Andean scenery and enjoy sites — the amazing Choquequirao Valley for nearly 50 years. immersive cultural experiences. and Machu Picchu — in just 8 days. ACTIVITIES LODGING CLIMATE Strenuous hiking to remote Three nights of camping; Weather can be erratic in the ruins high in the mountains, four comfortable mountains at higher altitudes, rewarded with spectacular views. -

Searching for Machu Picchu: Discovery and Adventure in the Andes of Peru

Searching for Machu Picchu: Discovery and Adventure in the Andes of Peru May 26-June 3, 2017 $3,950/person Lodge-to-lodge exploration of Inca trails and selected sites on horseback and foot from Cusco to Machu Picchu An educational journey to key Inca ruins finishing with an interpretive visit to Machu Picchu led by Colorado Collage alumnus- archaeologist, Gary Ziegler, and Cusco-based expeditions expert, Edwin Duenas We offer alternatives for those wishing to experience this itinerary without riding horses. We have combined these options within this one itinerary to allow couples and friends with diverse abilities and interests to travel together. Itinerary: Day 1) Friday, May 26: This is a travel day from home. You may choose to arrive on a night flight to Lima connecting with an early flight to Cusco, or if arriving earlier, plan a layover in Lima. We can help with arrangements and a suggested itinerary. Day 2) Saturday, May 27: We meet your arrival at the Cusco airport. The afternoon is scheduled for a walking introduction to the archaeological and colonial highlights of the old capital of the Inca universe. We visit the impressive ruins of Sacsayhuaman overlooking Cusco. Our leader describes the colorful rituals and ceremonies that would have taken place at the massive walled limestone constructions and sculptured terraces surrounding the immense central plaza. We finish with a summary of the battle here in 1536 which ended the life of Juan Pizarro. In the evening, we gather for drinks, dinner and discussion. We lodge at a favorite downtown hotel. Day 3) Sunday, May 28: We drive to the rim of the Cusco basin to meet the waiting horses. -

Guide to the Midterm

FYS 1100 Guide to the Midterm A. People: In this section of the test, you need to be able to identify and/or describe briefly who the following people were. You can expect to answer true/false and multiple-choice questions related to the identity and social-historical importance of these people. When studying their names, try to answer questions like: Why were these people historically or culturally important? How are they related Hiram Bingham, the discovery of Machu Picchu, the Incan civilization or the Spanish conquest? Agustín Lizárraga Franciso Pizarro Simón Bolívar Antonio de la Calancha Garcilaso de la Vega Theodore Roosevelt Antonio Raimondi Georgia OKeeffe Thor Heyerdahl Atahualpa Melchor Arteaga Titu Cusi Cacique Saavedra Pachacuti Tupac Amaru Chasqui Prefect J.J. Nuñez Viracocha Elihu Root Sayri Tupac B. Places and Objects: In this section of the test you will need to identify the following places and objects. In some cases you will need to provide a short definitions or examples of what each place or object was or why it was important. When studying for this section, try to answer questions like: What are these objects/places? Why were they historically or culturally important? Aclla-Huasi Cumara Intihuatana Andenes Cuy Quechua Bar-Holds Eye-Bonder Quilcas Bolas Hacienda Quipus Ceque Huaca Sacsayhuamán Champi Huilca Salineras de Maras Chicha jora Incan Irrigation Tambo Choquequirao Incan Mummies Tambomachay Coca Leaves Incan Stone Urumbamba Coricancha Incan Trail Vitcos C. Essay. In this section of the test, you will need to write a short essay related to one of the following topics. -

Astronomy of the Incas

DEL-090 v2, March 24th, 2014 Astronomy of the Incas GLORIA is funded by the European Union 7th Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n° 283783 Astronomy of the Incas (Total Lunar Eclipse 2014) CODE: DEL-090 VERSION: 02A DATE: March 25th, 2014 http://gloria-project.eu 1/19 DEL-090 v2, March 24th, 2014 Astronomy of the Incas Authors: Miguel Ángel Pío Jiménez (IAC) Lorraine HANLON (UCD) Miquel SERRA-RICART (IAC) Collaborators: Juan Carlos CASADO (tierrayestrellas.com) Luciano NICASTRO (INAF) Revised by: Carlos PÉREZ DEL PULGAR (UMA) Approved by: Alberto J. CASTRO-TIRADO (CSIC) http://gloria-project.eu 2/19 DEL-090 v2, March 24th, 2014 Astronomy of the Incas http://gloria-project.eu 3/19 DEL-090 v2, March 24th, 2014 Astronomy of the Incas Distribution List: Name Affiliation Date Luciano NICASTRO INAF March 17th, 2014 Miquel SERRA-RICART IAC March 17th, 2014 Lorraine HANLON UCD March 17th, 2014 Alberto CASTRO-TIRADO IAA-CSIC March 17th, 2014 Raquel CEDAZO UPM March 17th, 2014 Carlos PÉREZ DEL PULGAR UMA March 17th, 2014 ALL March 25th, 2014 http://gloria-project.eu 4/19 DEL-090 v2, March 24th, 2014 Astronomy of the Incas http://gloria-project.eu 5/19 DEL-090 v2, March 24th, 2014 Astronomy of the Incas Change Control Issue Date Section Page Change Description 01.A 17/03/2014 All All First version 01.B 24/03/2014 All All Second version with additions and corrections 02.A 25/03/2014 All All Final distributed version Reference Documents Nº Document Name Code Version http://gloria-project.eu 6/19 DEL-090 v2, March 24th, 2014 Astronomy of the Incas Table of Contents 1.Objectives of the activity....................................................................................................................................... -

Vitcos, the Last Inca Capital

Glass. Fl ^9 Book. teM PRESENTED BY 46M2- V ^tmttxtan Jttrftquarian <$«is£t| VITCOS, x& THE LAST INCA CAPITAL BY HIRAM BINGHAM Director of the Yale Peruvian Expedition Reprinted from the Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society for April, 1912. WORCESTER, MASSACHUSETTS, U.S.A. PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY 1912 The Davis Press Worcester, Mass. Author & •\ ,1 VITCOS, THE LAST INCA CAPITAL. I. The origin of the Yale Peruvian Expedition of 1911 lay in my desire to solve the problem of the last Inca capital and the country occupied by Manco Inca and his successors for thirty-five years after his revolt against Pizarro. On a journey across Peru from Cuzco to Lima on mule-back, in 1909, 1 I had visited Choqque- quirau, an interesting group of ruins on a ridge sur- rounded by precipices 6,000 feet above the bottom of the Apurimac valley. The local traditions had it that this place was the home of Manco Inca after he fled from Pizarro's conquering hosts. 2 It was recorded that he took with him into the fastnesses of Vilcabamba3 a great quantity of treasure, besides his family and courtiers. Nevertheless, Prescott does not mention the name of Vilcabamba, and only says that Manco fled into the most inaccessible parts of the cordillera. When the great Peruvian geographer, Raimondi, visited this region about the middle of the XIX Century no one seems to have thought of telling him there were any ruins in the Vilcabamba valley or indeed in the Uru- bamba valley below Ollantaytambo. He did, however, remember that the young Inca Manco had established 1 Described on pp.