Vitcos, the Last Inca Capital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Machu Picchu & the Sacred Valley

Machu Picchu & The Sacred Valley — Lima, Cusco, Machu Picchu, Sacred Valley of the Incas — TOUR DETAILS Machu Picchu & Highlights The Sacred Valley • Machu Picchu • Sacred Valley of the Incas • Price: $1,995 USD • Vistadome Train Ride, Andes Mountains • Discounts: • Ollantaytambo • 5% - Returning Volant Customer • Saqsaywaman • Duration: 9 days • Tambomachay • Date: Feb. 19-27, 2018 • Ruins of Moray • Difficulty: Easy • Urumbamba River • Aguas Calientes • Temple of the Sun and Qorikancha Inclusions • Cusco, 16th century Spanish Culture • All internal flights (while on tour) • Lima, Historic Old Town • All scheduled accommodations (2-3 star) • All scheduled meals Exclusions • Transportation throughout tour • International airfare (to and from Lima, Peru) • Airport transfers • Entrance fees to museums and other attractions • Machu Picchu entrance fee not listed in inclusions • Vistadome Train Ride, Peru Rail • Personal items: Laundry, shopping, etc. • Personal guide ITINERARY Machu Picchu & The Sacred Valley - 9 Days / 8 Nights Itinerary - DAY ACTIVITY LOCATION - MEALS Lima, Peru • Arrive: Jorge Chavez International Airport (LIM), Lima, Peru 1 • Transfer to hotel • Miraflores and Pacific coast Dinner Lima, Peru • Tour Lima’s Historic District 2 • San Francisco Monastery & Catacombs, Plaza Mayor, Lima Cathedral, Government Palace Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner Ollyantaytambo, Sacred Valley • Morning flight to Cusco, The Sacred Valley of the Incas 3 • Inca ruins: Saqsaywaman, Rodadero, Puca Pucara, Tambomachay, Pisac • Overnight: Ollantaytambo, Sacred -

Peru's Inca Trail

PERU’S INCA TRAIL YOUNG ALUMNI TOUR 2020 BE PART OF THE TRADITION APRIL 4 - U.S. DEPARTURE DATE APRIL 5 - LAND TOUR START DATE APRIL 10 - TRAVEL HOME (arrive U.S. APRIL 11) BASE LAND PACKAGE FROM: $ 1,875 START YOUR ADVENTURE. Dear Young Alumni and Friends! Can you think of a better way to travel than with fellow Razorback Young Alumni? The University of Arkansas young alumni travel program offers you this opportunity by bringing you together with individuals in the same age range, with similar backgrounds and experiences, while enriching you on well-designed, hassle-free tours of the world. Travel with young alumni and friends of peer institutions, ages 22 – 35. These programs provide social, cultural, and recreational activities and many opportunities for learning enrichment and enjoying a connection back to the University of Arkansas alumni family. They are of great quality and value, operated by a travel company with over 40 years of experience in the young professional travel market. In this brochure you will find a detailed itinerary, travel dates and pricing. If you have any questions about our young alumni travel program, please contact us by emailing our tour operator, AESU, at [email protected] or call 800-638-7640. Sincerely, Brandy Cox Brandy Cox Associate Vice Chancellor & Executive Director for Arkansas Alumni Association, Inc. TRAVEL INSURANCE We highly recommend travel insurance. (Some schools or alumni associations may offer travel insurance to you at a reduced rate.) WWW.AESU.COM/UARK 2 PERU’S INCA TRAIL 8 DAYS P L A C E S V I S I T E D : Cusco - Machu Picchu - Sacred Valley of the Incas - Ollantaytambo - Aguas Calientes A B O U T T H E T R I P : Considered one of the most famous archaeological sites on the continent, the Inca citadel of Machu Picchu exceeds every visitor's expectations. -

Who We Are? - MACHUPICCHU TERRA S.R.L

Who We Are? - MACHUPICCHU TERRA S.R.L INCA TRAIL MACHU PICCHU is a brand MACHUPICCHU TERRA, Travel Agency and Tour Operator authorized to sell Inca Trail Machu Picchu. Our company is located in Cusco, the capital of the Inca Empire and the Tourist Capital of South America. We created this web site considering that availability for the Inca Trail Machu Picchu is quickly exhausted; since it is limited to only 500 people per day (including support staff porters, chefs, guides, etc.) making it extremely necessary booking several months in advance; at least 6 months in advance. MACHU PICCHU TERRA, feels proud to provide superior service to all our customers, and we manage all services necessary to operate and organize all the packages offered, cars, minibuses, equipment, office-qualified staff, specialized assistants and guides professionals. Whether you are looking for a trip to Peru that includes a hike to Machu Picchu or just a relaxing family vacation, it is our mission to MACHUPICCHU TERRA work with you to create your trip to Peru. We welcome all types of customers with special travel interests, economic and Premium. Our ex cellent service always searches at any time and satisfy all customers throughout Peru. All MACHUPICCHU TERRA packages have been prepared by our travel consultants with experience and knowledge, our company MACHUPICCHU TERRA is based on 4 different categories of hotels: Basic Class, based on 2 stars hotels. Premium Class, based on 4 stars hotels. Economy Class, based on 3 stars hotels. VIPs Class, based on 5 stars hotels. Legitimacy of Inca Trail Machu Picchu MACHU PICCHU TERRA is an Authorized Agency by the Ministry of Culture, the assigned code is: MA0473, responsible and efficient company willing to provide the best service. -

Generated with Expertpdf Html to Pdf Converter

ARTS & CULTURE Jul 20, 2017 Sacred Valley, Peru: How to Plan the Perfect Trip SARAH SCHLICHTER Exploring Peru’s Sacred Valley of the Incas feels Save This Story like going back in time. Centuries-old Inca terraces spill down green, misty hillsides. Women in traditional Andean dress stroll along the cobblestone streets of colonial towns, long black braids trailing down their backs. Colorful village markets display soft alpaca sweaters, hats, and ponchos woven by hand. The Sacred Valley is tucked between Cusco and Machu Picchu, running along the Urubamba River from Pisac to Ollantaytambo. Travelers with limited time often skip the Sacred Valley in their rush to see Machu Picchu, but the valley’s picturesque towns and well-preserved Inca ruins are worth a day or two in their own right. The Sacred Valley has an additional benefit for travelers hoping to acclimate to the region’s altitude before visiting Machu Picchu: Most of the valley sits several hundred feet lower than Cusco. When to Visit the Sacred Valley For the best chance of dry weather, visit the Sacred Valley during its high season between June and August. The rainiest part of the year is November through March. Come during the shoulder-season months—April, May, September, and October —for slightly smaller crowds and lower prices than you’d find in high season, without an excessive threat of rain. Top Sights in the Sacred Valley Pisac: Famous for its Sunday market, in which farmers come from all over the Sacred Valley with a colorful bounty of local fruit and vegetables, Pisac is also worth a visit for its large Inca ruins. -

Highlights of Peru V2020

HIGH LIG H T S OF PER U HIGHLIGHTS OF PERU Experience Cusco from it's different angles, Cusco city, sacred valley and Machu Picchu. Expert guides will make your trip fascinating bringing ancient cultures to life. With a selection of stunning hotels, trains and bespoke EXPLORE FURTHER Enhance your 8-day itinerary with these exciting options. experiences spread across Peru’s most spectacular destinations, the Belmond Journeys in Peru team Belmond Andean Explorer - Cusco to Puno and Arequipa: has perfected the art of creating immersive Peruvian Join South America's first luxury sleeper train to Puno. escapes to leave you spellbound. Visit Raqch’i, La Raya, witness the sunrise at Lake Titicaca A jewel in South America's crown, Peru encapsulates before sailing to the Uros floating islands and Taquile everything we love about travel: time-honored traditions, Island. Admire Lake Lagunillas and the ancient Sumbay vibrant cultures and wild landscapes. Cave paintings. Finally, plunge into the Colca Canyon. Join us to explore this captivating, mystical realm of lost Amazon River: Fly from Lima to Iquitos. Board the Aria civilizations and tangible history. Journey to the beating Amazon, a luxury riverboat, and cruise along the mighty heart of the Land of the Incas. jungle waterway alighting to explore the rainforest. E I G H T - D AY IT I NER A R Y combined with the mysticism of the sacred valley. DAY 1 DAY 5 Arrive at Lima International Airport where one of our representatives Travel to Machu Picchu aboard Peru Rail Vistadome train. Enjoy will be waiting to escort you to Belmond Miraflores Park. -

Water Resources Management and Agriculture in the Highlands of South Peru from Incas Times to the Present

國立中山大學海洋環境及工程學系 博士論文 Department of Marine Environment and Engineering National Sun Yat-sen University Doctorate Dissertation 南秘魯地區從印加時期至今之水資源管理與農業灌溉使用 Water resources management and agriculture in the highlands of South Peru from Incas times to the present 研究生 : 王星 Enrique Meseth Macchiavello 指導教授 : 于嘉順 博士 Dr. Jason C.S. Yu 中華民國 一百零三年十月 October 2014 国立中山大学研究生学位論文審定書 本校海洋環境度工程筆糸博士班 研究生王 呈(学菰:DOO5040009)所提論文 南秘魯地直後印加時期至今之水資源管理興農業潅漑使用 WaterresourcesmanagementandagrlCultureinthehighlandsof SouthPeru宜omIncastimestothepresent 於中華民国宵籍藍若輩。舗査並奉行ロ 学位考試委員条章: 召集人疎放葦 委員干嘉順_鼓_ 委 員 尤結正 四国報国 委員高志明馬‘ま車 委 員 陸暁埼 委 員 委 員 委 員 委 員 指尊教授(干喜順) 囲 Acknowledgements The author would like to thank the following in this research project: National Sun Yat-Sen University NSYSU, Department of Marine Environment and Engineering, Kaohsiung, for supplying research equipment for this project Professor Jason Yu, for providing advice and suggestions - National Sun Yat-Sen University NSYSU, Department of Marine Environment and Engineering, Kaohsiung Dr. Hao-Cheng Yu, Yu-Chih Hsiao, classmates and staff from the Department of Marine Environment and Engineering at NSYSU for all their support Professor Shiau-Yun Lu, Chia-Wen Hsu MSc, and Huan-Min Chen MSc, for their support and training on GIS - National Sun Yat-Sen University NSYSU, Department of Marine Environment and Engineering, Kaohsiung Professor Su-Hwa Chen and Dr Liang-Chi Wang, for their advice and support on palynology analysis - National Taiwan University NTU, Institute of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Taipei Professor Michael Buzinny, for his advice and radiocarbon dating analysis - Marzeev Institute of Hygiene and Medical Ecology of the Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine Professor Jimmy Kao, for his advice on thesis and publications issues - National Sun Yat-Sen University NSYSU, Institute of Environmental Engineering, Kaohsiung Professor Wei-Hsiang Chen, for his lectures on climate change and advice on thesis and publications issues - National Sun Yat-Sen University NSYSU, Institute of Environmental Engineering, Kaohsiung Dir. -

PERU UNIQUE EXPERIENCE 2020 8 Days - 7 Nights Country : PERU Category : Boutique - Deluxe Accommodation : Hotel

CUSCO & INCA TREK PERU PERU UNIQUE EXPERIENCE 2020 8 days - 7 nights Country : PERU Category : Boutique - Deluxe Accommodation : Hotel Day 1: ARRIVAL IN CUSCO Type of Transport Specification Departure Arrival Baggage Weight per Alowance Luggage Flight: Lima - Cusco Suggested time: Morning On arrival to Cusco city, you will be met by one of our representative and transferred to your hotel. *We do recommend to rest this day to get acclimatized to the altitude. Hotel : La Casona Inkaterra Category : Suite Patio Altitude : 3,399 m.a.s.l. / 11,152 ft. Average Temperature : 15°C / 59°F Day 2: CUSCO This morning, you will be picked up from your hotel, and you will visit the surrounding ruins of the city of Cusco: Sacsayhuaman, this huge Inca fortress is built on three overlapping platforms. Then, visit Cusco's Historical Inca and Spanish Colonial Monuments, such as the Main Square, known in Inca times as Huacaypata or the Warrior's Square; it was the scene for many key events in Cusco's history. Continue onto the Church and Convent of Santo Domingo, a Spanish construction belonging to the Dominican Order built upon the foundations of the Inca temple of Koricancha or Temple of the Sun. Koricancha (in Quechua, site of gold) was the main religious building of the Incas dedicated to the worship of the Sun and whose walls, according to the chroniclers, were plated with sheets of gold. Magnificent blocks of finely carved stone were used in its construction. We will visit the San Pedro Market to admire the day-to-day activities of the locals. -

Ollan- Taytambo

Contact: Martin Harbaum Office: (511) 215-6000 - Ext: 2405 Cell: +51 998033553 Email: [email protected] domiruthperutravel.com peru4x4adventures.com General information based on wikipedia files All pictures Copyright © Martin Harbaum Ollan- taytambo Ollantaytambo is a town and an Inca It is located at an altitude of 2,792 meters (9,160 feet) above sea archaeological site in southern Peru level in the district of Ollantaytambo, province of Urubamba, some 60 kilometers northwest of the Cusco region. During the Inca Empire, Ollantaytambo was the city of Cusco.. royal estate of Emperor Pachacuti who conquered the region, built the town and a ceremonial center. At the time of the Spanish conquest of Peru it served as a stronghold for Manco Inca Yupanqui, leader of the Inca resistance. Nowadays it is an important tourist attraction on account of its Inca buildings and as one of the most common starting points for the three- day, four-night hike known as the Inca Trail. History: Around the mid-15th century, the Inca emperor Pachacuti conquered and razed Ollantaytambo; the town and the nearby region were incorporated into his personal estate.[2] The emperor rebuilt the town with sumptuous constructions and undertook extensive works of terracing and irrigation in the Urubamba Valley; the town provided lodging for the Inca nobility while the terraces were farmed by yanaconas, retainers of the emperor.[3] After Pachacuti’s death, the estate came under the administration of his panaqa, his family clan.[4] During the Spanish conquest of Peru Ollantaytambo served as a temporary capital for Manco Inca, leader of the native resistance against the conquistadors. -

Peru and the Next Machu Picchu

Global Heritage Fund Peru and the Next Machu Picchu: Exploring Chavín and Marcahuamachuco October 10 - 20, 2012 Global Heritage Fund Peru and the Next Machu Picchu: Exploring Chavín and Marcahuamachuco October 10 - 20, 2012 Clinging to the Andes, between the parched coastal desert and the lush expanse of the Amazon rainforest, Peru is far more than Machu Picchu alone. For thou- sands of years, long before the arrival of the Inca, the region was home to more than 20 major cultures, all of them leaving behind clues to their distinctive identities. With more than 14,000 registered archaeological and heritage sites, Peru has a well-deserved reputation as a veritable treasure-trove for anyone interested in ancient cultures and archaeology. Ancient, colonial, and modern Peru is a country with many faces. In the com- pany of Global Heritage Fund staff, encounter some of Peru’s most remarkable FEATURING: civilizations through the objects, structures, and archaeological clues that con- Dr. John W. Rick tinue to be uncovered. Associate Professor of Anthropology Stanford University John Rick is an associate professor of anthropology at Stanford University and also serves as Curator of Anthropology at the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for the Visual Arts, Stanford University. He earned his Ph.D. from Michigan in 1978. His interests in- clude prehistoric archaeology and anthropology of band-level hunter-gatherers, stone tool studies, analytical methodology, animal domestication and Pachacamac, Peru. South American archaeology. Dr. Rick has been di- Trip Highlights recting the excavations at the UNESCO World Heri- tage Site of Chavín de Huántar since 1995. -

Inca-Trail-Choquequirao-8-Days.Pdf

Who We Are? - MACHUPICCHU TERRA S.R.L INCA TRAIL MACHU PICCHU is a brand MACHUPICCHU TERRA, Travel Agency and Tour Operator authorized to sell Inca Trail Machu Picchu. Our company is located in Cusco, the capital of the Inca Empire and the Tourist Capital of South America. We created this web site considering that availability for the Inca Trail Machu Picchu is quickly exhausted; since it is limited to only 500 people per day (including support staff porters, chefs, guides, etc.) making it extremely necessary booking several months in advance; at least 6 months in advance. MACHU PICCHU TERRA, feels proud to provide superior service to all our customers, and we manage all services necessary to operate and organize all the packages offered, cars, minibuses, equipment, office-qualified staff, specialized assistants and guides professionals. Whether you are looking for a trip to Peru that includes a hike to Machu Picchu or just a relaxing family vacation, it is our mission to MACHUPICCHU TERRA work with you to create your trip to Peru. We welcome all types of customers with special travel interests, economic and Premium. Our ex cellent service always searches at any time and satisfy all customers throughout Peru. All MACHUPICCHU TERRA packages have been prepared by our travel consultants with experience and knowledge, our company MACHUPICCHU TERRA is based on 4 different categories of hotels: Basic Class, based on 2 stars hotels. Premium Class, based on 4 stars hotels. Economy Class, based on 3 stars hotels. VIPs Class, based on 5 stars hotels. Legitimacy of Inca Trail Machu Picchu MACHU PICCHU TERRA is an Authorized Agency by the Ministry of Culture, the assigned code is: MA0473, responsible and efficient company willing to provide the best service. -

Travel Guide to Machu Picchu

THE ULTIMATE TRAVEL GUIDE TO MACHU PICCHU Free step-by-step guide to planning and organising your Machu Picchu adventure! Publisher: Best of Peru Travel Guides (First Edition - April 2016) For general enquiries, listings, distribution and advertising information please contact us at: [email protected] Copyright notice: All contents copyright © Best of Peru Travel 2016 Text & Maps: © Best of Peru Travel 2016 Photos: © Best of Peru Travel 2016 & © Marcos Garcia/MGP Images All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any Best of Peru Travel is an online travel means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, reading or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher and copyright guide for independent travellers who are owner. looking for the best Lima, Cusco, Machu Every effort has been made to ensure that the information in this document is accurate at the time of going to press. Some details, Picchu and the Sacred Valley in Peru have however, such as prices, telephone numbers, opening hours, to offer. Want to know where to get the travel information and website addresses are liable to change. Best of Peru Travel accept no responsibility for any loss, injury or best Pisco sour in Cusco, the best lunch in inconvenience sustained by anyone using this information. Lima or which is the best hotel in Machu Editor’s note: Prices are in Peruvian Soles (S/.) unless otherwise stated in US$. All Picchu? Look no further... Visit us here! prices are guide prices only and are based on an exchange rate of 3.42 Peruvian Soles (PEN) to the US Dollar at the time of publication. -

Machu Picchu Was Rediscovered by MACHU PICCHU Hiram Bingham in 1911

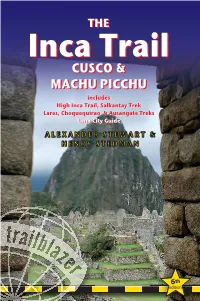

Inca-6 Back Cover-Q8__- 22/9/17 10:13 AM Page 1 TRAILBLAZER Inca Trail High Inca Trail, Salkantay, Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks + Lima Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks Salkantay, High Inca Trail, THETHE 6 EDN ‘...the Trailblazer series stands head, shoulders, waist and ankles above the rest. Inca Trail They are particularly strong on mapping...’ Inca Trail THE SUNDAY TIMES CUSCOCUSCO && Lost to the jungle for centuries, the Inca city of Machu Picchu was rediscovered by MACHU PICCHU Hiram Bingham in 1911. It’s now probably MACHU PICCHU the most famous sight in South America – includesincludes and justifiably so. Perched high above the river on a knife-edge ridge, the ruins are High Inca Trail, Salkantay Trek Cusco & Machu Picchu truly spectacular. The best way to reach Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks them is on foot, following parts of the original paved Inca Trail over passes of Lima City Guide 4200m (13,500ft). © Henry Stedman ❏ Choosing and booking a trek – When Includes hiking options from ALEXANDER STEWART & to go; recommended agencies in Peru and two days to three weeks with abroad; porters, arrieros and guides 35 detailed hiking maps HENRY STEDMAN showing walking times, camp- ❏ Peru background – history, people, ing places & points of interest: food, festivals, flora & fauna ● Classic Inca Trail ● High Inca Trail ❏ – a reading of The Imperial Landscape ● Salkantay Trek Inca history in the Sacred Valley, by ● Choquequirao Trek explorer and historian, Hugh Thomson Plus – new for this edition: ❏ Lima & Cusco – hotels,