Comparative Readings of the Lebanese Media System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutional Patriotism in Lebanon

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg MAURUS REINKOWSKI Constitutional Patriotism in Lebanon Originalbeitrag erschienen in: New perspektives on Turkey 16 (1997), S. [63] - 85 CONSTITUTIONAL PATRIOTISM IN LEB ON Maurus Reinkowski* In this paper I will discuss the options of political identity the Lebanese have at their disposal against the background of the German experience. Germany and Lebanon, states at first glance completely different from each other, show some similarity in their historical experience. In the context of this comparison I will discuss constitu- tional patriotism, a political concept in circulation in Germany over the last fifteen years or so, and its potential application in the Lebanese case. Constitutional patriotism, unlike many other concepts originating in the West, has yet not entered the political vocabulary of the Middle East. The debate on democracy and the civil society is widespread in the whole of the Middle East, including Lebanon. Lebanon's political culture, polity and national identity, however, show some peculiar traits that might justify the introduction of the term constitutional patriotism into the Lebanese political debate. As democracy and civil society are both closely linked to the concept of constitutional patriotism they will be treated in the first chapter. The second chapter will be devoted to the question of whether and to what extent Lebanon differs from the mainstream of the modern Middle East's political history. I will venture to draw a parallel with the German "sonderweg" (deviant, peculiar way). The third section will present briefly the German discussion of constitutional patriotism and its innate link to the sonderweg. -

P40 Layout 1

In Damascus, a ‘Cinema Paradiso’ struggles38 to stay open SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2013 VENICE: Director Alexandros Avranas (C), actor Themis Panou and actress Eleni Roussinou pose on the red carpet as they arrive for the award ceremony of the 70th Venice Film Festival yesterday at Venice Lido. —AFP ritics have tipped movies from Britain, Japan and the inative tale of life in Japan between the two World Wars would A total of 20 films are competing at the festival, including not have the patience to appreciate my slowness,” he told jour- United States to win Venice’s Golden Lion prize this year, be his last feature. James Franco’s necrophilia flick “Child of God”, the tale of a social nalists. Some critics suggested that, with the US mulling inter- Cdue to be announced at the world’s oldest film festival “In the past, I have said many times I would quit. This time, it’s outcast whose loneliness drives him to live in a cave and murder vening in the Middle East again, the jury might give the award to yesterday. British director Stephen Frears provoked a hugely for real,” the 72-year-old said in Tokyo. He had become too old women to have sex with their bodies. Errol Morris’s “The Unknown Known”, an interview with former enthusiastic response with his charming tragi-comedy for the kind of craftsmanship and physical work required for US actor Scott Haze-who isolated himself for three months US defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld. “Philomena”, the true tale of a mother’s search for her son after major commercial projects, he added. -

LE MONDE/PAGES<UNE>

www.lemonde.fr 58 ANNÉE – Nº 17830 – 1,20 ¤ – FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE --- VENDREDI 24 MAI 2002 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI 0123 A Moscou, DES LIVRES L’école de Luc Ferry Bush et Poutine Roberto Calasso Grecs à Montpellier Illettrisme, enseignement professionnel, autorité : les trois priorités du ministre de l’éducation consacrent un Le cinéma et l’écrit LE NOUVEAU ministre de l’édu- f rapprochement cation nationale, Luc Ferry, expose Un entretien avec INCENDIE dans un entretien au Monde ses le nouveau ministre « historique » trois priorités : la lutte contre l’illet- de la jeunesse L’ambassade d’Israël trisme, la valorisation de l’enseigne- ment professionnel et la consolida- et de l’éducation LORS de sa première visite officiel- à Paris détruite dans la tion de l’autorité des professeurs, le en Russie, le président américain nuit. Selon la police, le qu’il lie à la sécurité. Pour l’illettris- George W. Bush signera avec Vladi- me, Luc Ferry reproche à ses prédé- f « Il faut revaloriser mir Poutine, vendredi 24 mai au feu était accidentel p. 11 cesseurs de n’avoir « rien fait Kremlin, un traité de désarmement depuis dix ans ». Il insiste sur le res- la pédagogie nucléaire qualifié d’« historique » et MAFIA pect des horaires de lecture et du travail » à l’école visant à « mettre fin à la guerre froi- d’écriture, ainsi que sur la prise en de ». Les deux pays s’engagent à Dix ans après la mort charge des jeunes en difficulté. réduire leurs arsenaux stratégiques à L’enseignement professionnel doit f Médecins : un niveau maximal de 2 200 ogives à du juge Falcone p. -

Online Practices of Media Accountability in Lebanon

No. 6/2011 June | 2011 New Media – Old Problems Online Practices of Media Accountability in Lebanon Judith Pies, Philip Madanat & Christine Elsaeßer MediaAcT Working Paper series on ‘Media Accountability Practices on the Internet’ MediaAcT Working Paper 6/2011 Editors: Heikki Heikkilä & David Domingo English Language Editor: Marcus Denton of OU Derettens Journalism Research and Development Centre, University of Tampere, Finland 2011 This study is part of a collection of country reports on media accountability practices on the Internet. You can find more reports and a general introduction to the methodology and concepts of the reports at: http://www.mediaact.eu/online.html The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n° 244147. The information in this document is the outcome of the EU project Media Accountability and Transparency in Europe (MediaAcT). The research reflects only the authors’ views and the European Union is not liable for Newany use Media that may –be Oldmade Problems:of the information Onlinecontained therein. Practices The user ofthereof Media uses the information at their sole risk and liability. New Media – Old Problems: Online Practices of Media Accountability in Lebanon Judith Pies, Philip Madanat & Christine Elsaeßer Summary Lebanon’s media has been envied for its press freedom and high quality by many Arabs from the region for decades. After 15 years of civil war the media had quickly started to flourish again. Yet, internal and external observers have been concerned about the close links between the media and political and religious groups that have led to highly politicized journalism. -

A Conversation with Raghida Dergham

TM: Welcome everybody to this sixth installment in the Harvard Kennedy School American University in Cairo series of conversations with Arab thought leaders on the 2020 U.S. election and America's changing role in the Middle East. I’m going to turn this over to my co-pilot Karim Haggag to introduce our distinguished guest for today but let me Just remind everybody what it is we are doing here. Each weeK we've been meeting with leading Arabs from the worlds of policy practice and ideas to explore their perceptions of the current season of politics in the United States and to get their sense of where they thinK the United States, the world's sole superpower, is heading, and particularly, what all of this means for the Middle East. So far in this series, we've interviewed some really interesting and extraordinary people, including prime minister Ayad Allawi, the Emirati intellectual AbdulKhaleq Abdulla, the Iraqi-Emirati Journalist Mina al-Oraibi, and these conversations will soon be available on our website and on podcast streaming services. We also have one more conversation. This is the penultimate conversation before we break for the winter, one more conversation next weeK with the Saudi editor of the al-Arabiya English, Mohammed Alyahya, and we hope that you'll Join us for that. Let me now turn it over to my co-pilot in this endeavor, Karim Haggag of the American University in Cairo School of Global affairs and Public Policy. Karim. KH: ThanK you, TareK, and thanK you everyone for Joining us for this afternoon's discussion. -

Programme-2006.Pdf

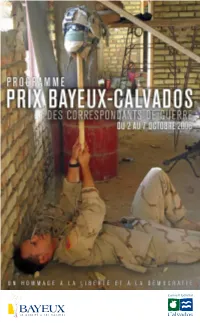

Programme PRIX BAYEUX-CALVADOS Édition 2006 DES CORRESPONDANTS DE GUERRE 2006 Lundi 2 octobre P Prix des lycéens J’ai le plaisir de vous Basse-Normandie présenter la 13e édition Mardi 3 octobre du Prix Bayeux-Calvados P Cinéma pour les collégiens des Correspondants de Guerre. Mercredi 4 octobre P Ouverture des expositions Fenêtre ouverte sur le monde, sur ses conflits, sur les difficultés du métier d’informer, Jeudi 5 octobre ce rendez-vous majeur des médias internationaux et du public rappelle, d’année en année, notre attachement à la démocratie et à son expression essentielle : P Soirée grands reporters : la liberté de la presse. Liban, nouveau carrefour Les débats, les projections et les expositions proposés tout au long de cette semaine de tous les dangers offrent au public et notamment aux jeunes l’éclairage de grands reporters et le décryptage d’une actualité internationale complexe et souvent dramatique. Vendredi 6 octobre Cette année plus que jamais, Bayeux témoignera de son engagement en inaugurant P Réunion du jury avec Reporters sans frontières, le « Mémorial des Reporters », site unique en Europe, international dédié aux journalistes du monde entier disparus dans l’exercice de leur profession pour nous délivrer une information libre, intègre et sincère. P Soirée hommage et projection en avant-première J’invite chacune et chacun d’entre vous à venir nous rejoindre du 2 au 7 octobre du film “ L’Étoile du Soldat ” à Bayeux, pour partager cette formidable semaine d’information, d’échange, d’hommage et d’émotion. de Christophe De Ponfilly PATRICK GOMONT Samedi 7 octobre Maire de Bayeux P Réunion du jury international et du jury public P Inauguration du Mémorial des reporters avec Reporters sans frontières P Salon du livre VOUS Le Prix du public, catégorie photo, aura lieu le samedi 7 octobre, de 10 h à 11 h, à la Halle aux Grains P SOUHAITEZ Table ronde sur la sécurité de Bayeux. -

'Pinkoes Traitors'

‘PINKOES AND TRAITORS’ The BBC and the nation, 1974–1987 JEAN SEATON PROFILE BOOKS First published in Great Britain in !#$% by Pro&le Books Ltd ' Holford Yard Bevin Way London ()$* +,- www.pro lebooks.com Copyright © Jean Seaton !#$% The right of Jean Seaton to be identi&ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act $++/. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN +4/ $ /566/ 545 6 eISBN +4/ $ /546% +$6 ' All reasonable e7orts have been made to obtain copyright permissions where required. Any omissions and errors of attribution are unintentional and will, if noti&ed in writing to the publisher, be corrected in future printings. Text design by [email protected] Typeset in Dante by MacGuru Ltd [email protected] Printed and bound in Britain by Clays, Bungay, Su7olk The paper this book is printed on is certi&ed by the © $++6 Forest Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-!#6$ CONTENTS List of illustrations ix Timeline xvi Introduction $ " Mrs Thatcher and the BBC: the Conservative Athene $5 -

A Main Document V202

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: TELEVISION NEWS AND THE STATE IN LEBANON Jad P. Melki, Doctor of Philosophy, 2008 Dissertation directed by: Professor Susan D. Moeller College of Journalism This dissertation studies the relationship between television news and the state in Lebanon. It utilizes and reworks New Institutionalism theory by adding aspects of Mitchell’s state effect and other concepts devised from Carey and Foucault. The study starts with a macro-level analysis outlining the major cultural, economic and political factors that influenced the evolution of television news in that country. It then moves to a mezzo-level analysis of the institutional arrangements, routines and practices that dominated the news production process. Finally, it zooms in to a micro-level analysis of the final product of Lebanese broadcast news, focusing on the newscast, its rundown and scripts and the smaller elements that make up the television news story. The study concludes that the highly fragmented Lebanese society generated a similarly fragmented and deeply divided political/economic elite, which used its resources and access to the news media to solidify its status and, by doing so, recreated and confirmed the politico-sectarian divide in this country. In this vicious cycle, the institutionalized and instrumentalized television news played the role of mediator between the elites and their fragmented constituents, and simultaneously bolstered the political and economic power of the former while keeping the latter tightly held in their grip. The hard work and values of the individual journalist were systematically channeled through this powerful institutional mechanism and redirected to serve the top of the hierarchy. -

The Oral History and Memory of Ras Beirut: Exceptional Narratives of Co-Existence

Middle East Studies Association (MESA) Conference Washington, DC, November 2014 The Oral History and Memory of Ras Beirut: Exceptional Narratives of Co-existence Maria Bashshur Abunnasr, PhD This paper is a very condensed version of my past dissertation research and my current project on the oral history and memory of Ras Beirut sponsored by the Neighborhood Initiative at the American University of Beirut. For those of you who do not know Beirut, Ras Beirut is the western-most extension of the city and is most renown as the location of the American University of Beirut (AUB) founded by American missionaries in 1866 as the Syrian Protestant College. To many Ras Beirut is a place famous, indeed exceptional, for its association with tolerance, education, and cosmopolitanism. And that association is largely credited to AUB. The focus of this paper, however, is not on AUB’s role in Ras Beirut. It reverses the lens to consider the local community’s role in making Ras Beirut’s past through what I term, “narratives of coexistence.” Comprised of primarily (though not exclusively) Greek Orthodox Christians and Sunni Muslims, Ras Beirut’s local community claims its foundation is based on ta’ayoush, Arabic for coexistence. They consider their history of peaceful coexistence the bedrock of Ras Beirut’s exceptionalism that distinguished Ras Beirut from other parts of Beirut, of Lebanon, and of the region. While they recognize the presence of the AUB as momentous to the future shape of Ras Beirut as a cosmopolitan hub, their narratives insist on the influence, if not the determination, of their 1 coexistence on the missionary choice of Ras Beirut as the site for the College in the first place. -

On the Record

Website: www.iwmf.org Website: E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: Fax (202) 496-1977 (202) Fax Tel. (202) 496-1992 (202) Tel. Washington, DC 20006 DC Washington, 1625 K Street, NW, Suite 1275 Suite NW, Street, K 1625 Foundation Media Women’s International on the record “Journalists, by their very nature, represent the ultimate strength of an open society as well as its ultimate vulnerability.” Judea Pearl, father of slain journalist Daniel Pearl International Women’s Media Foundation Strengthening the Role of Women in the IWMFwire News Media Worldwide In This Issue 3 4 5 6 7 8 10 Former Courage Leadership, Updates on Board IWMF Honors 2006 IWMF Co-sponsors IWMF Names New World Update Winner Killed in Maisha Yetu Members, Courage Courage Awardees Panel Discussion Board Members Opportunities Russia Journalists Awardees Recognized March 2007 volume 17 no. 1 IWMF’s Upcoming Programs A Close-up Shot of the War in Iraq IWMF’s Elizabeth Neuffer Fellow has personal insight from working as a reporter in Iraq Elizabeth Neuffer Forum The 2007 Elizabeth Neuffer By Peggy Simpson Forum on Human Rights and Journalism will be held from hen Huda Ahmed U.S. policies, of mistakes made over and 10:30 a.m. to 1 p.m. March 29 was named the again, not just in Iraq, but also in Palestine at the John F. Kennedy Presi- IWMF’s 2006-07 and Lebanon. She wants to “understand dential Library in Boston. The Elizabeth Neuffer the point of view of the American govern- theme is “Women and Islam: Fellow, her mother ment, with Iraq and the whole Middle Understanding and Reporting.” Wtold her to “keep this happiness in your East,” she said, beyond promises about For more information visit: heart” in order to “keep your head on democracy and human rights. -

From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund

7/2019 From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund PUBLISHED BY THE SWEDISH INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS | UI.SE Abstract The Russian-Syrian relationship turns 75 in 2019. The Soviet Union had already emerged as Syria’s main military backer in the 1950s, well before the Baath Party coup of 1963, and it maintained a close if sometimes tense partnership with President Hafez al-Assad (1970–2000). However, ties loosened fast once the Cold War ended. It was only when both Moscow and Damascus separately began to drift back into conflict with the United States in the mid-00s that the relationship was revived. Since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Russia has stood by Bashar al-Assad’s embattled regime against a host of foreign and domestic enemies, most notably through its aerial intervention of 2015. Buoyed by Russian and Iranian support, the Syrian president and his supporters now control most of the population and all the major cities, although the government struggles to keep afloat economically. About one-third of the country remains under the control of Turkish-backed Sunni factions or US-backed Kurds, but deals imposed by external actors, chief among them Russia, prevent either side from moving against the other. Unless or until the foreign actors pull out, Syria is likely to remain as a half-active, half-frozen conflict, with Russia operating as the chief arbiter of its internal tensions – or trying to. This report is a companion piece to UI Paper 2/2019, Russia in the Middle East, which looks at Russia’s involvement with the Middle East more generally and discusses the regional impact of the Syria intervention.1 The present paper seeks to focus on the Russian-Syrian relationship itself through a largely chronological description of its evolution up to the present day, with additional thematically organised material on Russia’s current role in Syria. -

Khadija Daughtr of Khuwaylid

KHADIJA DAUGHTR OF KHUWAYLID In the year 595, Muhammed son of Abdullah, Prophet of Islam, was old enough to go with trade caravans in the company of other kinsmen from the populous Quraish tribe. But the financial position of his uncle, Abu Talib, who raised him after the death of his father, had become very weak because of the expenses of rifada and siqaya , the housing and feeding of pilgrims of the holy “House of God” which Abraham and Ishmael had rebuilt following damage caused by torrential rain. It was no longer possible for Abu Talib to equip his nephew, Muhammed, with merchandise on his own. He, therefore, advised him to act as agent for a noble lady, Khadija bint (daughter of) Khuwaylid, who was the wealthiest person in Quraish. Her genealogy joins with that of the Prophet at Qusayy. She was Khadija daughter of Khuwaylid ibn Asad ibn `Abdul-`Ozza ibn Qusayy. She, hence, was a distant cousin of Muhammed. The reputation which Muhammed enjoyed for his honesty and integrity led Khadija to willingly entrust her mercantile goods to him for sale in Syria. She sent him word through his friend Khazimah ibn Hakim, a relative of hers, offering him twice the commission she used to pay her agents to trade on her behalf. Muhammed, with the consent of his uncle Abu Talib, accepted her offer. Most references consulted for this essay make a casual mention of Khadija. This probably reflects a male chauvinistic attitude which does a great deal of injustice to this great lady, the mother of the faithful whose wealth contributed so much to the dissemination of Islam.