Mswela Unpublished (Dphil) 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 SEAT Report Jwaneng Mine

JWANENG MINE SEAT 3REPORT 2017 - 2020 Contents INTRODUCTION TO JWANENG MINE’S SEAT 14 EXISTING SOCIAL PERFORMANCE 40 1. PROCESS 4. MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES 1.1. Background and Objectives 14 4.1. Debswana’s Approach to Social Performance 41 and Corporate Social Investment 1.2. Approach 15 4.1.1. Approach to Social Performance 41 1.3. Stakeholders Consulted During SEAT 2017 16 4.1.2. Approach to CSI Programmes 41 1.4. Structure of the SEAT Report 19 4.2. Mechanisms to Manage Social Performance 41 2. PROFILE OF JWANENG MINE 20 4.3. Ongoing Stakeholder Engagement towards 46 C2.1. Overview of Debswana’s Operational Context 20 Social Performance Management 2.2. Overview of Jwaneng Mine 22 DELIVERING SOCIO-ECONOMIC BENEFIT 49 2.2.1. Human Resources 23 5. THROUGH ALL MINING ACTIVITIES 2.2.2. Procurement 23 5.1. Overview 50 2.2.3. Safety and Security 24 5.2. Assessment of Four CSI/SED Projects 52 2.2.4. Health 24 5.2.1. The Partnership Between Jwaneng Mine 53 Hospital and Local Government 2.2.5. Education 24 5.2.2. Diamond Dream Academic Awards 54 2.2.6. Environment 25 5.2.3. Lefhoko Diamond Village Housing 55 2.3. Future Capital Investments and Expansion 25 Plans 5.2.4. The Provision of Water to Jwaneng Township 55 and Sese Village 2.3.1. Cut-8 Project 25 5.3. Assessing Jwaneng Mine’s SED and CSI 56 2.3.2. Cut-9 Project 25 Activities 2.3.3. The Jwaneng Resource Extension Project 25 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS 58 (JREP) 6. -

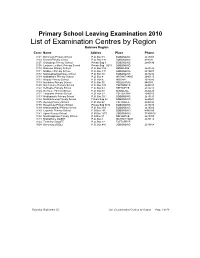

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization. Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ijagbemi, Bayo, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 17:13:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/196133 LAND TENURE REFORMS AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION IN BOTSWANA: IMPLICATIONS FOR URBANIZATION by Bayo Ijagbemi ____________________ Copyright © Bayo Ijagbemi 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2006 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Bayo Ijagbemi entitled “Land Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Thomas Park _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Stephen Lansing _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr David Killick _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Mamadou Baro Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

Kgatleng SUB District

Kgatleng SUB District VOL 5.0 KGATLENG SUB DISTRICT Population and Housing Census 2011 Selected Indicators for Villages and Localities ii i Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 3 Table of Contents Kgatleng Sub District Population And Housing Census 2011: Selected Indicators For Villages And Localities Preface 3 VOL 5,0 1.0 Background and Commentary 6 1.1 Background to the Report 6 Published by 1.2 Importance of the Report 6 STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone 2.0 Population Distribution 6 Phone: (267)3671300, 3.0 Population Age Structure 6 Fax: (267) 3952201 Email: [email protected] 3.1 The Youth 7 Website: www.cso.gov.bw/cso 3.2 The Elderly 7 4.0 Annual Growth Rate 7 5.0 Household Size 7 COPYRIGHT RESERVED 6.0 Marital Status 8 7.0 Religion 8 Extracts may be published if source is duly acknowledged 8.0 Disability 9 9.0 Employment and Unemployment 9 10.0 Literacy 10 ISBN: 978-99968-429-7-9 11.0 Orphan-hood 10 12.0 Access to Drinking Water and Sanitation 10 12.1 Access to Portable Water 10 12.2 Access to Sanitation 11 13.0 Energy 11 13.1 Source of Fuel for Heating 11 13.2 Source of Fuel for Lighting 12 13.3 Source of Fuel for Cooking 12 14.0 Projected Population 2011 – 2026 13 Annexes 14 iii Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 1 FIGURE 1: MAP OF KATLENG DISTRICT Preface This report follows our strategic resolve to disaggregate the 2011 Population and Housing Census report, and many of our statistical outputs, to cater for specific data needs of users. -

2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS REPORT II Keireng A

REPORT TO THE MINISTER FOR PRESIDENTIAL AFFAIRS, GOVERNANCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION ON THE 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS I REPORT Honourable Justice Abednego B. Tafa Mr. John Carr-Hartley Members of CHAIRMAN DEPUTY CHAIRMAN The Independent Electoral Commission Mrs. Agnes Setlhogile Mrs. Shaboyo Motsamai Dr. Molefe Phirinyane COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER Mrs. Martha J. Sayed Vacant COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS REPORT II Keireng A. Zuze Doreen L. Serumula SECRETARY DEPUTY SECRETARY Executive Management of the Secretariat Keolebogile M. Tshitlho Dintle S. Rapoo SENIOR MANAGER MANAGER CORPORATE SERVICES ELECTIONS AFFAIRS & FIELD OPERATIONS Obakeng B. Tlhaodi Uwoga H. Mandiwana CHIEF STATE COUNSEL MANAGER HUMAN RESOURCE & ADMINISTRATION 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS REPORT III Strategic Foundations ........................................................................................................................... I Members of The Independent Electoral Commission ................................................ II Executive Management of the Secretariat........................................................................... III Letter to The Minister for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Administration ............................................................................................................... 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................................................. 2 ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................... -

Ghanzi District Ngamiland District Central District Kgalagadi District

PL NO. COMPANY COMMODITY STATUS EXPIRY DATE AREA MINERAL RIGHT PL125/2009 A-cap Resources Botswana (Pty) Ltd Radioactive Minerals First Renewal 20141231 176 Energy MINERAL CONCESSION MAP OF ENERGY MINERALS FOR JULY 2014 PL138/2005 A-cap Resources Botswana (Pty) Ltd Radioactive Minerals Extension 20141231 214 Energy PL166/2010 African Coal & Gas Corpporation Limited Coal Original 20130630 533.8 Energy PL054/2005 African Energy Botswana (Pty) Ltd Coal Second Renewal 20120331 269.4 Energy PL055/2005 African Energy Botswana (Pty) Ltd Coal Extension 20140630 212 Energy PL057/2005 African Energy Botswana (Pty) Ltd Coal Extension 20140630 312 Energy PL687/2009 Amagram (Pty) Ltd Coal Original 20120930 240.1 Energy PL001/2013 Anglo Coal Botswana (Pty) Ltd Coal Original 20151231 67.1 Energy PL002/2013 Anglo Coal Botswana (Pty) Ltd CBM Original 20151231 200.2 Energy PL473/2009 Centre's Alliance Mines (Pty) Ltd Coal & Coalbed Methane First Renewal PL474/2009 Centre's Alliance Mines (Pty) Ltd Coal & Coalbed Methane First Renewal 20141231 336 Energy PL178/2010 Coal Fields Botswana (Pty) Ltd Coal & Coalbed Methane First Renewal 20150930 254 Energy PL425/2009 Daheng Group Botswana (Pty) Ltd Coal & Coalbed Methane Original 20120331 913 Energy PL426/2009 Daheng Group Botswana (Pty) Ltd Coal & Coalbed Methane First Renewal 20140930 249 Energy PL428/2009 Daheng Group Botswana (Pty) Ltd Coal & Coalbed Methane First Renewal 20140930 147 Energy PL035/2005 Exxaro Coal Botswana (Pty) Ltd Coalbed Methane Extension 20140630 770 Energy PL036/2005 Exxaro Coal Botswana -

Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards (Amendment) Order

CHAPTER 32:02 - TRIBAL LAND: SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION INDEX TO SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards (Amendment) Order Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards Order Tribal Land (Establishment of Land Tribunals) Order Tribal Land (Subordinate Land Boards) Regulations Tribal Land Regulations ESTABLISHMENT OF SUBORDINATE LAND BOARDS ORDER (under section 19) (15th June, 1973) ARRANGEMENT OF PARAGRAPHS PARAGRAPH 1. Citation 2. Establishment 3. Area of jurisdiction 4. Functions Schedule S.I. 47, 1973, S.I. 3, 1979, S.I. 125, 1979, S.I. 132, 1980, S.I. 78, 1981, S.I. 81, 1981, S.I. 110, 1981, S.I. 68, 1982, S.I. 5, 1984, S.I. 92, 1984, S.I. 36, 1986, S.I. 55,1987, S.I. 97, 1989, S.I. 45, 1992, S.I. 66, 1994, S.I. 53, 2002. 1. Citation Copyright Government of Botswana This Order may be cited as the Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards Order. 2. Establishment The subordinate land boards referred to in the second column of the Schedule hereto are established as the subordinate land boards within the district named in the first column of the said Schedule. 3. Area of jurisdiction The area of jurisdiction in respect of which each subordinate Land Board will perform its functions shall be the area or villages stated in relation to each subordinate land board in the third column of the Schedule. 4. Functions (1) The functions under customary law which vest in the subordinate land authority which are transferred to the subordinate land board shall include the hearing, grant or refusal of applications to use land for— ( a) building residences or extensions thereto; ( b) ploughing to a maximum extent of land determined by the tribal land board; ( c) grazing cattle or other stock; ( d) communal uses in the village. -

List of Schools Visited for Monitoring Visits

LIST OF SCHOOLS VISITED FOR MONITORING VISITS CENTRAL INSPECTORAL AREA LOCATION NAME OF SCHOOL MMADINARE Diloro Diloro MMADINARE Mmadinare Kelele MMADINARE Kgagodi Kgagodi MMADINARE Mmadinare Mmadinare MMADINARE Mmadinare Phethu Mphoeng MMADINARE Robelela Robelela MMADINARE Gojwane Sedibe MMADINARE Serule Serule MMADINARE Mmadinare Tlapalakoma BOTETI Rakops Etsile BOTETI Khumaga Khumaga BOTETI Khwee Khwee BOTETI Mopipi Manthabakwe BOTETI Mmadikola Mmadikola BOTETI Letlhakane Mokane BOTETI Mokoboxane Mokoboxane BOTETI Mokubilo Mokubilo BOTETI Moreomaoto Moreomaoto BOTETI Mosu Mosu BOTETI Motlopi Motlopi BOTETI Letlhakane Retlhatloleng Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Boitshoko Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Boswelakgomo Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Tebogo BOBIRWA Bobonong Bobonong BOBIRWA Gobojango Gobojango BOBIRWA Bobonong Mabumahibidu BOBIRWA Bobonong Madikwe BOBIRWA Mogapi Mogapi BOBIRWA Molalatau Molalatau BOBIRWA Bobonong Rasetimela BOBIRWA Semolale Semolale BOBIRWA Tsetsebye Tsetsebye 1 | P a g e MAHALAPYE WEST Bonwapitse Bonwapitse MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye Leetile MAHALAPYE WEST Mokgenene Mokgenene MAHALAPYE WEST Moralane Moralane MAHALAPYE WEST Mosolotshane Mosolotshane MAHALAPYE WEST Otse Setlhamo MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye St James MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye Tshikinyega MHALAPYE EAST Mahalapye Flowertown MHALAPYE EAST Mahalapye Mahalapye MHALAPYE EAST Matlhako Matlhako MHALAPYE EAST Mmaphashalala Mmaphashalala MHALAPYE EAST Sefhare Mmutle PALAPYE NORTH Goo-Sekgweng Goo-Sekgweng PALAPYE NORTH Goo-Tau Goo-Tau -

Lea Smme Directory 2016

www.lea.co.bw LEA SMME DIRECTORY 2016 Manufacturing Tourism Agriculture Services DISCLAIMER The information published in this document is for the sole purpose of marketing LEA registered SMME’s. LEA shall not be liable for any loss howsoever incurred as a result of use of content on this document in whole or in part. LEA further does not warrant that a business placing reliance on this document will generate certain results, nor does LEA guarantee any particular outcome of the application of the contents hereof to any situation. The clients and users hereby indemnifies and holds harmless LEA, its successors in title, agents and employees against any and all claims for loss or inconvenience arising out of the implementation by the user of the contents of this document or any annexure or addendum to it. www.lea.co.bw LEA SMME Directory 2016 LEA INCUBATORS NETWORK Vision To be the centre of excellence for entrepreneurship and sustainable SMME development in Botswana. LEA Mission To promote and facilitate entrepreneurship and SMME development through targeted interventions, in pursuit of economic diversification. Values Self-driven– We are passionate, eager to learn, persistent and determined to achieve personal goals so that the entire team achieves its desired results. Trasformational GABORONE LEATHER INDUSTRIES GLEN VALLEY HORTICULTURE leadership- We are inspired and self-led, motivated, INCUBATOR INCUBATOR innovative, innovative and Plot 4799 / 4800 Plot 63069 accountable to achieve Old Bedu Station Extension 67 maximum potential in a favourable environment. Macheng Way Private Bag X035 Private Bag 0301 Glen Valley Partnership- Through our Gaborone, Botswana Gaborone Botswana internal teamvork and Tel: (+267) 3105330 Tel: (+267) 3186309 effective partnership with stakeholders, our efforts are Fax: (+267) 3105334 Fax: (+267) 3186437 synergized resulting in the success of our clientele. -

BOTSWANA ENVIRONMENT STATISTICS 2016 Revised Version (RV)

BOTSWANA ENVIRONMENT STATISTICS 2016 Revised Version (RV) ----- ------- --- ---- --- -- ------ -------- -- -- -- --- - -- --- -- -- - - -- - -- -- - -- - - - - - - -- - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- -- -- - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - --- - --- - -- --- - - - - -- - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- ---- - - - -- - - -- -- - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - --- ----- - - - - - - - -- -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Public Primary Schools

PRIMARY SCHOOLS CENTRAL REGION NO SCHOOL ADDRESS LOCATION TELE PHONE REGION 1 Agosi Box 378 Bobonong 2619596 Central 2 Baipidi Box 315 Maun Makalamabedi 6868016 Central 3 Bobonong Box 48 Bobonong 2619207 Central 4 Boipuso Box 124 Palapye 4620280 Central 5 Boitshoko Bag 002B Selibe Phikwe 2600345 Central 6 Boitumelo Bag 11286 Selibe Phikwe 2600004 Central 7 Bonwapitse Box 912 Mahalapye Bonwapitse 4740037 Central 8 Borakanelo Box 168 Maunatlala 4917344 Central 9 Borolong Box 10014 Tatitown Borolong 2410060 Central 10 Borotsi Box 136 Bobonong 2619208 Central 11 Boswelakgomo Bag 0058 Selibe Phikwe 2600346 Central 12 Botshabelo Bag 001B Selibe Phikwe 2600003 Central 13 Busang I Memorial Box 47 Tsetsebye 2616144 Central 14 Chadibe Box 7 Sefhare 4640224 Central 15 Chakaloba Bag 23 Palapye 4928405 Central 16 Changate Box 77 Nkange Changate Central 17 Dagwi Box 30 Maitengwe Dagwi Central 18 Diloro Box 144 Maokatumo Diloro 4958438 Central 19 Dimajwe Box 30M Dimajwe Central 20 Dinokwane Bag RS 3 Serowe 4631473 Central 21 Dovedale Bag 5 Mahalapye Dovedale Central 22 Dukwi Box 473 Francistown Dukwi 2981258 Central 23 Etsile Majashango Box 170 Rakops Tsienyane 2975155 Central 24 Flowertown Box 14 Mahalapye 4611234 Central 25 Foley Itireleng Box 161 Tonota Foley Central 26 Frederick Maherero Box 269 Mahalapye 4610438 Central 27 Gasebalwe Box 79 Gweta 6212385 Central 28 Gobojango Box 15 Kobojango 2645346 Central 29 Gojwane Box 11 Serule Gojwane Central 30 Goo - Sekgweng Bag 29 Palapye Goo-Sekgweng 4918380 Central 31 Goo-Tau Bag 84 Palapye Goo - Tau 4950117