Taiwanese Aquaculture, Trade Governance, and Sustainability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Analects of Confucius

The analecTs of confucius An Online Teaching Translation 2015 (Version 2.21) R. Eno © 2003, 2012, 2015 Robert Eno This online translation is made freely available for use in not for profit educational settings and for personal use. For other purposes, apart from fair use, copyright is not waived. Open access to this translation is provided, without charge, at http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23420 Also available as open access translations of the Four Books Mencius: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23421 Mencius: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23423 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23422 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23424 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i MAPS x BOOK I 1 BOOK II 5 BOOK III 9 BOOK IV 14 BOOK V 18 BOOK VI 24 BOOK VII 30 BOOK VIII 36 BOOK IX 40 BOOK X 46 BOOK XI 52 BOOK XII 59 BOOK XIII 66 BOOK XIV 73 BOOK XV 82 BOOK XVI 89 BOOK XVII 94 BOOK XVIII 100 BOOK XIX 104 BOOK XX 109 Appendix 1: Major Disciples 112 Appendix 2: Glossary 116 Appendix 3: Analysis of Book VIII 122 Appendix 4: Manuscript Evidence 131 About the title page The title page illustration reproduces a leaf from a medieval hand copy of the Analects, dated 890 CE, recovered from an archaeological dig at Dunhuang, in the Western desert regions of China. The manuscript has been determined to be a school boy’s hand copy, complete with errors, and it reproduces not only the text (which appears in large characters), but also an early commentary (small, double-column characters). -

Taiwan's Nationwide Cancer Registry System of 40 Years: Past, Present

Journal of the Formosan Medical Association (2019) 118, 856e858 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect journal homepage: www.jfma-online.com Perspective Taiwan’s Nationwide Cancer Registry System of 40 years: Past, present, and future Chun-Ju Chiang a,b, Ying-Wei Wang c, Wen-Chung Lee a,b,* a Institute of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan b Taiwan Cancer Registry, Taipei, Taiwan c Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taipei, Taiwan Received 29 October 2018; accepted 15 January 2019 The Taiwan Cancer Registry (TCR) is a nationwide demonstrate that the TCR is one of the highest-quality population-based cancer registry system that was estab- cancer registries in the world.3 lished by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in 1979. The The TCR publishes annual cancer statistics for all cancer data of patients with newly diagnosed malignant cancer in sites, and the TCR’s accurate data is used for policy making hospitals with 50 or more beds in Taiwan are collected and and academic research. For example, the Health Promotion reported to the TCR. To evaluate cancer care patterns and Administration (HPA) in Taiwan has implemented national treatment outcomes in Taiwan, the TCR established a long- screening programs for cancers of the cervix uteri, oral form database in which cancer staging and detailed treat- cavity, colon, rectum, and female breast,4 and the TCR ment and recurrence information has been recorded since database has been employed to verify the effectiveness of 2002. Furthermore, in 2011, the long-form database these nationwide cancer screening programs for reducing began to include detailed information regarding cancer cancer burdens in Taiwan.5,6 Additionally, liver cancer was site-specific factors, such as laboratory values, tumor once a major health problem in Taiwan; however, since the markers, and other clinical data related to patient care. -

Democratic Values and Democratic Support in East Asia

Democratic Values and Democratic Support in East Asia Kuan-chen Lee [email protected] Postdoctoral fellow, Institute of Political Science, Academia Sinica Judy Chia-yin Wei [email protected] Postdoctoral fellow, Center for East Asia Democratic Studies, National Taiwan University Stan Hok-Wui Wong [email protected] Assistant Professor, Department of Applied Social Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University Karl Ho [email protected] Associate Professor, School of Economic, Political, and Policy Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas Harold D. Clarke [email protected] Ashbel Smith Professor, School of Economic, Political, and Policy Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas Introduction In East Asia, 2014 was an epochal year for transformation of social, economic and political orders. Students in Taiwan and Hong Kong each led a large scale social movement in 2014 that not only caught international attention, but also profoundly influenced domestic politics afterwards. According to literature of political socialization, it is widely assumed that the occurrences of such a huge event will produce period effects which bring socio-political attitudinal changes for all citizens, or at least, cohort effects, which affect political views for a group of people who has experienced the event in its formative years. While existing studies have accumulated fruitful knowledge in the socio-political structure of the student-led movement, the profiles of the supporters in each movement, as well as the causes and consequences of the student demonstrations in the elections (Ho, 2015; Hawang, 2016; Hsiao and Wan, 2017; Stan, forthcoming; Ho et al., forthcoming), relatively few studies pay attention to the link between democratic legitimacy and student activism. -

Modeling Incipient Use of Neolithic Cultigens by Taiwanese Foragers: Perspectives from Niche Variation Theory, the Prey Choice Model, and the Ideal Free Distribution

quaternary Article Modeling Incipient Use of Neolithic Cultigens by Taiwanese Foragers: Perspectives from Niche Variation Theory, the Prey Choice Model, and the Ideal Free Distribution Pei-Lin Yu Department of Anthropology, Boise State University, 1910 University Dr., Boise, ID 83725, USA; [email protected] Received: 3 June 2020; Accepted: 14 August 2020; Published: 7 September 2020 Abstract: The earliest evidence for agriculture in Taiwan dates to about 6000 years BP and indicates that farmer-gardeners from Southeast China migrated across the Taiwan Strait. However, little is known about the adaptive interactions between Taiwanese foragers and Neolithic Chinese farmers during the transition. This paper considers theoretical expectations from human behavioral ecology based models and macroecological patterning from Binford’s hunter-gatherer database to scope the range of responses of native populations to invasive dispersal. Niche variation theory and invasion theory predict that the foraging niche breadths will narrow for native populations and morphologically similar dispersing populations. The encounter contingent prey choice model indicates that groups under resource depression from depleted high-ranked resources will increasingly take low-ranked resources upon encounter. The ideal free distribution with Allee effects categorizes settlement into highly ranked habitats selected on the basis of encounter rates with preferred prey, with niche construction potentially contributing to an upswing in some highly ranked prey species. In coastal plain habitats preferred by farming immigrants, interactions and competition either reduced encounter rates with high ranked prey or were offset by benefits to habitat from the creation of a mosaic of succession ecozones by cultivation. Aquatic-focused foragers were eventually constrained to broaden subsistence by increasing the harvest of low ranked resources, then mobility-compatible Neolithic cultigens were added as a niche-broadening tactic. -

Multilevel Spatial Impact Analysis of High-Speed Rail and Station Placement: a Short-Term Empirical Study of the Taiwan HSR

T J T L U http://jtlu.org V. 13 N. 1 [2020] pp. 317–341 Multilevel spatial impact analysis of high-speed rail and station placement: A short-term empirical study of the Taiwan HSR Yu-Hsin Tsai Jhong-yun Guan National Chengchi University Dept. of Urban Development, Taipei City [email protected] Government [email protected] Yi-hsin Chung Dept. of Urban Development, Taipei City Government [email protected] Abstract: Understanding the impact of high-speed rail (HSR) services Article history: on spatial distributions of population and employment is important for Received: September 15, 2019 planning and policy concerning HSR station location as well as a wide Received in revised form: May range of complementary spatial, transportation, and urban planning 14, 2020 initiatives. Previous research, however, has yielded mixed results into the Accepted: May 26, 2020 extent of this impact and a number of influential factors rarely have been Available online: November 4, controlled for during assessment. This study aims to address this gap 2020 by controlling for socioeconomic and transportation characteristics in evaluating the spatial impacts of HSR (including station placement) at multiple spatial levels to assess overall impact across metropolitan areas. The Taiwan HSR is used for this empirical study. Research methods include descriptive statistics, multilevel analysis, and multiple regression analysis. Findings conclude that HSR-based towns, on average, may experience growing population and employment, but HSR-based counties are likely to experience relatively less growth of employment in the tertiary sector. HSR stations located in urban or suburban settings may have a more significant spatial impact. -

Proceedings of the Fifth International Fishers Forum on Marine Spatial Planning and Bycatch Mitigation

Proceedings of the Fifth International Fishers Forum on Marine Spatial Planning and Bycatch Mitigation Shangri-La Far Eastern Plaza Hotel Taipei, August 3-5, 2010 ` Editors: Eric Gilman Asuka Ishizaki David Chang Wei-Yang Liu Paul Dalzell ` !"#$%$!&& ''()*+$ #,--%#% +/&` #00#11#12213#` ####2#1#411512 1%62#00122##4 ##2% 7$"63(*!&38!3( 294:4#;9:<% 00###101, =>%7?5%:%@%A:?%;>1<%/&%Proceedings of the Fifth International Fishers Forum on Marine Spatial Planning and Bycatch Mitigation.` '+$% 402, ` !"#$%$!&& ''()*+$ >3,72%B%4 #,--%#% #2`#691 #116%6&6!!&/(% `11121411 1a42691#1 :#2% Table of Contents 1%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%7 SESSION SUMMARIES AND PRESENTATION ABSTRACTS >E4$%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%( SESSION 1: 9'>$99$@6: 78190F4 %%%%%%%%%%%%* 76>$7@@6676=6:6=>>6 #:%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%8 $$%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%/( 2### OPENING SESSION `,2 #4301 9>676=::>$$ Dr. Larry B. Crowder, :5+4%%%%%%* Dr. Wu-Hsiung Chen, Minister, Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan, Taiwan%%%%%%%%%( 9#12# # 9>676=>G$ Dr. David Hyrenbach'`+4 %%*! Mr. James Sha:= 2>E4A%%%%%%%/& +4":4W `120 Mr. Wen-Jung Hsieh `12#2`3 :#$@"39 1## 1>E# %%%%%%%%%%%%%/& Mr. Daniel Dunn:5+4%%%%%%%%%*8 Dr. Rebecca Lent:92`27 ##? 22+%$%6$4 %%%21 #2 Mr. Sean Martin1'@ Dr. Hsueh-Jung Lu69 %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%21 +4 %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%*( ="25, REPORTING ON COMMITMENTS 411#4##1 AND PROGRESS SINCE IFF1 Mr. Randall Owens="2 Ms. Kitty M. Simonds>E4: 5 %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%!& `%%%/* 2##4 24 01F1 Dr. Robin Warner+42%%%!* ###1 Mr. Paul Holthus19%%%%%%!8 * SESSION 2:$>$+:7>$99$@6: SESSION 3:77=76="A'9$>6$77L> 76>$7@@6676=6:6=>>6 $>7>$=9+$7676>7$'>7>$ Session 2A:>$>7L>$96=>$ Session 3A:77=76=$>6$77L>$>7>$ 6:@66>$ "A'6:6=76=:7$:$76$@@ $@>7$'>7>$76@+:76=9$@7$6@ $$%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%47 $$7L>6>7$'>7>$ 1##1 $$%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%71 6'71 Dr. -

Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies in Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China Timothy Robert Clifford University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Clifford, Timothy Robert, "In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2234. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2234 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2234 For more information, please contact [email protected]. In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China Abstract The rapid growth of woodblock printing in sixteenth-century China not only transformed wenzhang (“literature”) as a category of knowledge, it also transformed the communities in which knowledge of wenzhang circulated. Twentieth-century scholarship described this event as an expansion of the non-elite reading public coinciding with the ascent of vernacular fiction and performance literature over stagnant classical forms. Because this narrative was designed to serve as a native genealogy for the New Literature Movement, it overlooked the crucial role of guwen (“ancient-style prose,” a term which denoted the everyday style of classical prose used in both preparing for the civil service examinations as well as the social exchange of letters, gravestone inscriptions, and other occasional prose forms among the literati) in early modern literary culture. This dissertation revises that narrative by showing how a diverse range of social actors used anthologies of ancient-style prose to build new forms of literary knowledge and shape new literary publics. -

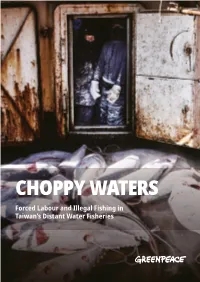

Choppy Waters Report

CHOPPY WATERS Forced Labour and Illegal Fishing in Taiwan’s Distant Water Fisheries TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 2 2. Introduction 3 Published in March 2020 by: Greenpeace East Asia 3. Methodology 6 No.109, Sec. 1, Chongqing S. Rd, Zhongzheng Dist., Taipei City 10045, Taiwan This report is written by Greenpeace East Asia (hereafter re- 4. Findings 8 ferred to as Greenpeace) to assist public education and scien- Indications of forced labour in Taiwan’s distant water fisheries: Cases and evidence 9 tific research, to encourage press coverage and to promote Reports of the fisher story 9 the awareness of environmental protection. Reading this report is considered as you have carefully read and fully un- Reports of abusive working and living conditions 12 derstand this copyright statement and disclaimer, and agree Possible violations of international standards and Taiwanese labour regulations 13 to be bound by the following terms. Potential cases of IUU fishing 18 Copyright Statement: Potential at-sea transshipments based on AIS records 19 This report is published by Greenpeace. Greenpeace is the exclusive owner of the copyright of this report. 5. How tainted tuna catch could enter the market 22 Disclaimer: FCF’s global reach 22 1. This report is originally written in English and translated How tainted catch might enter the global supply chain via FCF 23 into Chinese subsequently. In case of a discrepancy, the English version prevails. 2. This report is ONLY for the purposes of information sha- ring, environmental protection and public interests. There- 6. Taiwan’s responsibilities 25 fore should not be used as the reference of any investment The international environmental and social responsibility of seafood companies 27 or other decision-making process. -

Crustal Structures from the Wuyi-Yunkai Orogen to the Taiwan Orogen: the Onshore-Offshore Wide-Angle Seismic Experiments of the TAIGER and ATSEE Projects

Tectonophysics 692 (2016) 164–180 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Tectonophysics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tecto Crustal structures from the Wuyi-Yunkai orogen to the Taiwan orogen: The onshore-offshore wide-angle seismic experiments of the TAIGER and ATSEE projects Yao-Wen Kuo a,Chien-YingWanga,HaoKuo-Chena,⁎, Xin Jin b,c,Hui-TengCaib,c,Jing-YiLina, Francis T. Wu d, Horng-Yuan Yen a, Bor-Shouh Huang e, Wen-Tzong Liang e, David Okaya f, Larry Brown g a Dept. of Earth Sciences, National Central University, Zhongli, Taiwan b College of Civil Engineering, Fuzhou University, Fuzhou, China c Earthquake Administration of Fujian Province, Fuzhou, China d Dept. of Geological and Environmental Science, State University of New York at Binghamton, Binghamton, USA e Institute of Earth Sciences, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan f Dept. of Earth Science, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA g Dept. of Earth and Atmosphere Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA article info abstract Article history: Knowledge of the crustal structure is important for understanding the tectonic framework and geological evolu- Received 8 March 2015 tion of southeastern China and adjacent areas. In this study, we integrated the datasets from the TAIGER (TAiwan Received in revised form 9 August 2015 Integrated GEodynamic Research) and ATSEE (Across Taiwan Strait Explosion Experiment) projects to resolve Accepted 20 September 2015 onshore-offshore deep crustal seismic profiles from the Wuyi-Yunkai orogen to the Taiwan orogen in southeast- Available online 30 September 2015 ern China. Three seismic profiles were resolved, and the longest profile was 850 km. -

THE ROLE Oa= Ms .AGRECULTURAL Lsecmk M TAIWAN's Ecomwc ’DEVELORMENT

THE ROLE oa= ms .AGRECULTURAL lsecmk m TAIWAN'S ecomwc ’DEVELORMENT Thesis for the Degree of .Ph. D. MICHIGAN STATE UNWERSITY Charles Hsi—chung -Kao_ 19164 7 _—_—‘-.- L 114231: LIBRAR Y 7‘ Ilil‘lllllllillllIlllllllllullllillilllilllltllllllflil‘lllil .L State 3 1293 10470 0137 Michigan University This is to certify that the thesis entitled THE ROLE OF THE AGRICULTURAL SECTOR IN TAIWAN 'S ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT presented by Charles Hal-Chung Kao has been accepted towards fulfillment of the requirements for Ph.D. degree in Agricultural Economics .2 Major professor Date August 13, 1964 l i l 1 0-169 ,\ . .‘ . n i” .53 ’2'; .p I: I" Q1. JJ . 'J‘. AUG 2 4 2012 ABSTRACT THE ROLE OF THE AGRICULTURAL SECTOR IN TAIWAN'S ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT by Charles Hsi-chung Kao The role of the agricultural sector in Taiwan's economic develOpment was examined, following Kuznets, in three aspects, i.e., product, market and factor, with special reference to the post-war period. The product aspect of the agricultural sector was analyzed in two periods: lQOl-HO and 19u5-62. It was concluded that the means used in increasing the crop yields in 1901-40 provides "an example of the Japanese approaches applied in a different setting." But this achievement was not attained by merely employing resources that had low Opportunity costs as Professor Bruce Johnston claims. Two modern inputs: fertilizers and irrigation, were used at quite high costs. Further progress was made in agriculture during the post-war period. The total agricultural production increased at an average growth rate of u.9 percent per year in 1953-60, well exceeding the high population growth of 3.5 percent per year. -

THE MEDIA's INFLUENCE on SUCCESS and FAILURE of DIALECTS: the CASE of CANTONESE and SHAAN'xi DIALECTS Yuhan Mao a Thesis Su

THE MEDIA’S INFLUENCE ON SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF DIALECTS: THE CASE OF CANTONESE AND SHAAN’XI DIALECTS Yuhan Mao A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Language and Communication) School of Language and Communication National Institute of Development Administration 2013 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis The Media’s Influence on Success and Failure of Dialects: The Case of Cantonese and Shaan’xi Dialects Author Miss Yuhan Mao Degree Master of Arts in Language and Communication Year 2013 In this thesis the researcher addresses an important set of issues - how language maintenance (LM) between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech (also known as dialects) - are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries. In particular, how the television and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over others is examined. These issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature - a sub-branch of sociolinguistics - particularly with respect to LM literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. The researcher found support to confirm two positive correlations: the correlative relationship between the number of productions of dialectal television series (and films) and the distribution of the dialect in question, as well as the number of dialectal speakers and the maintenance of the dialect under investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express sincere thanks to my advisors and all the people who gave me invaluable suggestions and help. -

Growing Demand for Organics in Taiwan Stifled by Unique

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 9/20/2017 GAIN Report Number: TW17006 Taiwan Post: Taipei Growing Demand for Organics in Taiwan Stifled by Unique Regulatory Barriers Report Categories: Special Certification - Organic/Kosher/Halal Approved By: Mark Petry Prepared By: Ping Wu and Andrew Anderson-Sprecher Report Highlights: The United States exported $28 million worth of organic fruits and vegetables to Taiwan in 2016, up 74 percent from the year before. In comparison, U.S. organic exports to the rest of the world grew just one percent in 2016. Taiwan is now the fourth largest export market for U.S. organic products. Despite its strong market potential, Taiwan has a number of unique requirements that make exporting organic products to the market challenging. Executive Summary: In 2016, exports of U.S. exported $28 million worth of organic fruits and vegetables to Taiwan, making it our fourth largest export market. This represents a 74 percent increase from the year before, compared to a one percent growth in organic exports to the rest of the world. The highest selling U.S. organic products to Taiwan were head lettuce, cauliflower, broccoli, celery, and apples. Despite its strong market potential, Taiwan has a number of unique requirements that make exporting organic products to the market challenging. The key issue is a requirement that imported organic products must apply to Taiwan authorities for approval to be labeled as organic even if Taiwan has recognized the exporting countries’ organic standards as equivalent.