An Overview, Survey, and Critique of Administrating Cross-Border Insolvencies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What a Creditor Needs to Know About Liquidating an Insolvent BVI Company

What a creditor needs to know about liquidating GUIDE an insolvent BVI company Last reviewed: October 2020 Contents Introduction 3 When is a company insolvent? 3 What is a statutory demand? 3 Written request for payment 3 Is it essential to serve a statutory demand? 3 What must a statutory demand say? 3 Setting aside a statutory demand 4 How may a company be put into liquidation? 4 Qualifying resolution 4 Appointment 4 Liquidator's powers 4 Court order 5 Who may apply? 5 Application 5 Debt should be undisputed 5 When does a company's liquidation start? 5 What are the consequences of a company being put into liquidation? 5 Assets do not vest in liquidator 5 Automatic consequences 5 Restriction on execution and attachment 6 Public documents 6 Other consequences 6 Effect on contracts 6 How do creditors claim in a company's liquidation? 7 Making a claim 7 Currency 7 Contingent debts 7 Interest 7 Admitting or rejecting claims 7 What is a creditors' committee? 7 Establishing the committee 7 2021934/79051506/1 BVI | CAYMAN ISLANDS | GUERNSEY | HONG KONG | JERSEY | LONDON mourant.com Functions 7 Powers 8 What is the order of distribution of the company's assets? 8 Pari passu principle 8 Excluded assets 8 Order of application 8 How are secured creditors affected by a company's liquidation? 8 General position 8 Liquidator challenge 8 Claiming in the liquidation 8 Who are preferential creditors? 9 Preferential creditors 9 Priority 9 What are the claims of current and past shareholders? 9 Do shareholders have to contribute towards the company's debts? -

Secured Financing and Priorities Among Creditors

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1979 Secured Financing and Priorities among Creditors Anthony T. Kronman Thomas H. Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Anthony T. Kronman & Thomas H. Jackson, "Secured Financing and Priorities among Creditors," 88 Yale Law Journal 1143 (1979). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Secured Financing and Priorities Among Creditors* Thomas H. Jacksont and Anthony T. Kronmant One of the principal advantages of a secured transaction is the protection it provides against the claims of competing creditors. A creditor asserting a security interest in his debtor's property is likely to find himself in competition with a wide assortment of other claimants. For example, his security interest may be challenged by another creditor with a consensual security interest, by a creditor with a judgment or execution lien, by a creditor claiming a right to the collateral under some general statutory entitlement such as a repair- man's lien, by a seller to or a buyer from the debtor, or by the debtor's trustee in bankruptcy. To a considerable extent, the value of a security interest depends upon the degree to which it insulates the secured party from the claims of the debtor's other creditors.1 Article 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code contains detailed rules for resolving conflicts between secured creditors and various third parties-rules that tell the secured party what he must do in order to prevent his security interest from being overridden by a competing claimant, or, conversely, what a competitor must do in order to cir- cumvent an existing security interest in the debtor's property. -

Partially Secured Creditors: Their Rights and Remedies Under Chapter XI of the Bankruptcy Act John C

Louisiana Law Review Volume 37 | Number 5 Summer 1977 Partially Secured Creditors: Their Rights and Remedies Under Chapter XI of the Bankruptcy Act John C. Anderson Repository Citation John C. Anderson, Partially Secured Creditors: Their Rights and Remedies Under Chapter XI of the Bankruptcy Act, 37 La. L. Rev. (1977) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol37/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARTIALLY SECURED CREDITORS: THEIR RIGHTS AND REMEDIES UNDER CHAPTER XI OF THE BANKRUPTCY ACT John C. Anderson* Discussions of the rights of secured creditors under the Bankruptcy Act are conspicuous by their absence.' Ironically, the Act speaks the least about those creditors receiving the most.2 In bankruptcy liquidation cases under Chapters I-VII of the Bankruptcy Act, secured claims are entitled to the highest priority, being paid in preference to all other claims and 3 administrative expenses when the security for such claims is liquidated. Since most bankrupt estates are heavily encumbered by mortgages and liens, nearly all of the assets of the estates, after being liquidated, are paid toward secured claims. Accordingly, after the payment of secured debts, administrative expenses and then priority claims, there is usually little or nothing left to pay dividends to unsecured creditors. While there is a paucity of discussion about secured creditors in liquidation proceedings, similar discussions of the rights and remedies of secured creditors in arrangements under Chapter XI of the Bankruptcy Act are virtually nonexistent.4 Once again, secured creditors are integral par- * Member, Baton Rouge Bar. -

Overview of the Fdic As Conservator Or Receiver

September 26, 2008 OVERVIEW OF THE FDIC AS CONSERVATOR OR RECEIVER This memorandum is an overview of the receivership and conservatorship authority of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (the “FDIC”). In view of the many and complex specific issues that may arise in this context, this memorandum is necessarily an overview, but it does give particular reference to counterparty issues that might arise in the case of a relatively large complex bank such as a significant regional bank and outlines elements of the FDIC framework which differ from a corporate bankruptcy. This memorandum has three parts: (1) background on the legal framework governing FDIC resolutions, highlighting changes and developments since the 1990s; (2) an outline of six distinctive aspects of the FDIC approach with comparison to the bankruptcy law provisions; and (3) a final section illustrating issues and uncertainties in the FDIC resolutions process through a more detailed review of two examples – treatment of loan securitizations and participations, and standby letters of credit.1 Relevant additional materials include: the pertinent provisions of the Federal Deposit Insurance (the "FDI") Act2 and FDIC rules3, statements of policy4 and advisory opinions;5 the FDIC Resolution Handbook6 which reflects the FDIC's high level description of the receivership process, including a contrast with the bankruptcy framework; recent speeches of FDIC Chairman 1 While not exhaustive, these discussions are meant to be exemplary of the kind of analysis that is appropriate in analyzing any transaction with a bank counterparty. 2 Esp. Section 11 et seq., http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/1000- 1200.html#1000sec.11 3 Esp. -

The Unsecured Creditor's Bargain: a Reply, 80 Va

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 1994 The nsecU ured Creditor's Bargain: A Reply Susan Block-Lieb Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Susan Block-Lieb, The Unsecured Creditor's Bargain: A Reply, 80 Va. L. Rev. 1989 (1994) Available at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/740 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNSECURED CREDITOR'S BARGAIN: A REPLY Susan Block-Lieb* INTRODUCTION U UNLIKE Law and Economics scholars who view secured lend- ing as a consensual relationship benefiting not only debtors and their secured parties but also the debtors' unsecured creditors, Lynn LoPucki describes secured transactions as a subsidy because they benefit debtors and their secured creditors at the expense of unsecured creditors. He believes security "is an institution in need of basic reform" because it "tends to misallocate resources by imposing on unsecured creditors a bargain to which many, if not most, of them have given no meaningful consent."' He divides these unsecured creditors into two groups: involuntary creditors, and -

April 2020 COVID-19 and EXAMINERSHIP – WHAT the EXAMINER WANTS YOU to KNOW

April 2020 COVID-19 AND EXAMINERSHIP – WHAT THE EXAMINER WANTS YOU TO KNOW For further information Following our articles on: on any of the issues discussed in this article 1. Emergency liquidity for businesses adversely affected by the please contact: economic impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: https://www.dilloneustace.com/legal-updates/the-abc-and- de-of-emergency-liquidity-solutions; 2. Standstill Agreements as the first item out of the financial first aid kit: https://www.dilloneustace.com/legal- updates/running-to-standstill; and 3. Ireland’s public sector lifeboat for SMEs and small mid-cap businesses: https://www.dilloneustace.com/legal- updates/liquid-spirit-government-guaranteed-working-capital- facilities-for-irish-smes-adversely-affected-by-the-covid-19- pandemic, Jamie Ensor Partner, Insolvency we turn to the main items for consideration by stakeholders in DD: + 353 (0)1 673 1722 circumstances where examinership is the chosen mechanism for [email protected] rehabilitation and long term recovery for a company in financial difficulty as a consequence of the Pandemic. Testing times In the current climate, it is unfortunately all too possible to imagine a business that has dealt with a severe business interruption by following the government’s advice and has: • lowered variable costs (while participating in the COVID-19 Wage Subsidy Scheme); • delayed discretionary spending on replacing or improving Richard Ambery assets, new projects and research and development; Consultant, Capital Markets DD: + 353 (0)1 673 1003 [email protected] -

A Primer on Second Lien Term Loan Financings by Neil Cummings and Kirk A

A Primer on Second Lien Term Loan Financings By Neil Cummings and Kirk A. Davenport ne of the more noticeable developments in can protect their interests in the collateral by requiring the debt markets in the last year has been second lien lenders to agree to a “silent second” lien. Othe exponential increase in the number of Second lien lenders can often be persuaded to second lien fi nancings in the senior bank loan mar- agree to this arrangement because a silent second ket. Standard & Poor’s/Leveraged Commentary & lien is better than no lien at all. In addition, under Data Team reports that second lien fi nancings raised the intercreditor agreement, in most deals, the more than $7.8 billion in the fi rst seven months of second lien lenders expressly reserve all of the 2004 alone, compared with about $3.2 billion for all rights of an unsecured creditor, subject to some of 2003. important exceptions. In this article, we discuss second lien term loans All of this sounds very simple, and fi rst and second marketed for sale in the institutional loan market, lien investors may be tempted to ask why it takes with a goal of providing both an overview of the pages of heavily negotiated intercreditor terms to product and an understanding of some of the key document a silent second lien. The answer is that business and legal issues that are often at issue. a “silent second” lien can span a range from com- In a second lien loan transaction, the second lien pletely silent to fairly quiet, and where the volume lenders hold a second priority security interest on the control is ultimately set varies from deal to deal, assets of the borrower. -

The Secured Creditor's Right to Full Liquidation Value in Corporate Reorganization

COMMENTS The Secured Creditor's Right to Full Liquidation Value in Corporate Reorganization A corporation forced by business failure into a state of legal insolvency or inability to pay its debts as they mature may petition the federal bankruptcy court to enforce a plan of reorganization, or may be brought into the court by a petition filed by its major credi- tors, under chapter X1 or section 772 of the Federal Bankruptcy Act. Corporate reorganizations, which readjust the debt and equity obli- gations of the insolvent corporation, essentially provide a substitute for a forced liquidation sale of the debtor corporation. 3 It may be difficult or impossible to sell a large bankrupt enterprise intact, and a sale in lot or bulk at spot market prices, especially in hard times, is likely to bring disastrously little for distribution among creditors and other claimants. 4 In order to preserve the business as an operat- ing entity until business fortunes improve, and to salvage "going concern" value, the spot market is bypassed. A fictional reorganiza- tion value is computed, which is said to represent the fair or intrin- sic value of the business, and investors are compensated for their claims in securities of the reorganized enterprise.5 Reorganization is primarily beneficial to junior creditors and equity interests, since they are protected from the adverse conse- quences of a forced sale at market prices.6 At the same time, how- ever, the reorganization process is geared to the protection of senior and secured creditors.' Although the secured creditor is denied his 1 11 U.S.C. -

Implementing Strategies for the Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency: the Divergence in Asia-Pacific and Lessons for UNCITRAL

Emory Bankruptcy Developments Journal Volume 36 Issue 1 A Tribute to James H.M. Sprayregen 2020 Implementing Strategies for the Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency: The Divergence in Asia-Pacific and Lessons for UNCITRAL Wai Yee Wan Gerard McCormack Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/ebdj Recommended Citation Wai Y. Wan & Gerard McCormack, Implementing Strategies for the Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency: The Divergence in Asia-Pacific and Lessons for UNCITRAL, 36 Emory Bankr. Dev. J. 59 (2020). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/ebdj/vol36/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory Bankruptcy Developments Journal by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SMU Classification: Restricted MCCORMACKWANPROOFS_4.30.20 5/3/2020 3:43 PM IMPLEMENTING STRATEGIES FOR THE MODEL LAW ON CROSS-BORDER INSOLVENCY: THE DIVERGENCE IN ASIA- PACIFIC AND LESSONS FOR UNCITRAL Wai Yee Wan* Gerard McCormack** ABSTRACT The UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency (“Model Law”) was conceived with the aim of providing a framework for states to obtain consistency in the recognition of foreign insolvency proceedings and granting relief in aid of the foreign courts. The Model Law has achieved moderate success internationally and four states in the Asia-Pacific, namely Australia, Singapore, Japan, and Korea, have enacted legislation based on the Model Law. Scholars agree on the importance of consistent implementation of the Model Law in managing cross-border insolvency to achieve quick, certain, and predictable outcomes. -

A Normative Framework for Cross-Border Insolvency Choice of Law John A

Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 10 2014 Beyond Carve-Outs and Toward Reliance: A Normative Framework for Cross-Border Insolvency Choice of Law John A. E. Pottow Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl Recommended Citation John A. Pottow, Beyond Carve-Outs and Toward Reliance: A Normative Framework for Cross-Border Insolvency Choice of Law, 9 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. (2014). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl/vol9/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. BEYOND CARVE-OUTS AND TOWARD RELIANCE: A NORMATIVE FRAMEWORK FOR CROSS-BORDER INSOLVENCY CHOICE OF LAW John A. E. Pottow* The title of this Article purports to develop a normative framework for cross-border insolvency choice of law. That can be a task of varying scope, so at the outset any pretense of ambition for a wholly new choice of law model should be dispelled. Indeed, at the most generalized level, bankruptcy choice of law theory has already been fully ventilated in the well-rehearsed universalism versus territorialism debates.1 And it has been settled. The universalists, at least as a normative matter, appear to have won: choice of law, as it is increasingly accepted, should be determined by the debtor’s center of main interests (COMI). 2 But no sooner did the universalists -

Secured Creditors Must Be Diligent to Protect Bankruptcy Post-Petition Interest and Costs 2016 Emerging Issues 7481

LexisNexis® Emerging Issues Analysis Research Solutions | October 2016 David A. Wender and Thomas P. Clinkscales on Secured Creditors Must Be Diligent to Protect Bankruptcy Post-Petition Interest and Costs 2016 Emerging Issues 7481 Click here for more Emerging Issues Analyses related to this Area of Law. U.S. District Judge Louise W. Flanagan has affirmed a ruling from the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina in In re Construction Supervision Services , Inc .1 that a secured creditor that was oversecured on the date the debtor filed for bankruptcy was not entitled to a superpriority administrative expense claim under 11 U.S.C. § 507 (b) for post-petition interest, costs, or fees. Background When Construction Supervision Services, Inc. (the debtor) filed its voluntary Chapter 11 petition on January 24, 2012, the secured creditor held claims against the estate totaling $1,265,868.55, including principal and matured interest as of the petition date (the “secured claim”). The secured claim was oversecured as of the filing because it was secured by the debtor’s accounts receivable, which were valued at over $5 million as of the petition date. During the course of the case, the court granted various motions related to the secured claim, including authorizing the use of cash collateral and ordering the debtor to pay the secured creditor adequate protection payments. The debtor made both credits and debits to its accounts receivable during the course of the case. Two months after the case was filed, the court allowed various subcontractors and material providers (the “subcontractors”) who had not perfected their liens prior to the petition date to perfect them post-petition. -

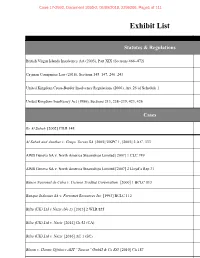

Exhibit List

Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page1 of 111 Exhibit List Statutes & Regulations British Virgin Islands Insolvency Act (2003), Part XIX (Sections 466–472) B Cayman Companies Law (2016), Sections 145–147, 240–243 United Kingdom Cross-Border Insolvency Regulations (2006), Art. 25 of Schedule 1 United Kingdom Insolvency Act (1986), Sections 213, 238–239, 423, 426 Cases Re Al Sabah [2002] CILR 148 Al Sabah and Another v. Grupo Torras SA [2005] UKPC 1, [2005] 2 A.C. 333 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 1 CLC 749 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 31 Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Cosmos Trading Corporation [2000] 1 BCLC 813 Banque Indosuez SA v. Ferromet Resources Inc [1993] BCLC 112 Bilta (UK) Ltd v Nazir (No 2) [2013] 2 WLR 825 Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2014] Ch 52 (CA) Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2016] AC 1 (SC) Bloom v. Harms Offshore AHT “Taurus” GmbH & Co KG [2010] Ch 187 Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page2 of 111 Exhibit List Cases, continued Re Paramount Airways Ltd [1993] Ch 223 Picard v. Bernard L Madoff Investment Securities LLC BVIHCV140/2010 B Rubin v. Eurofinance SA [2013] 1 AC 236; [2012] UKSC 46 Singularis Holdings Ltd v. PricewaterhouseCoopers [2014] UKPC 36, [2015] A.C. 1675 Stichting Shell Pensioenfonds v. Krys [2015] AC 616; [2014] UKPC 41 Other Authorities McPherson’s Law of Company Liquidation (4th ed. 2017) Anthony Smellie, A Cayman Islands Perspective on Trans-Border Insolvencies and Bankruptcies: The Case for Judicial Co-Operation , 2 Beijing L.