World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tunisia Summary Strategic Environmental and Social

PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT: ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT COUNTRY: TUNISIA SUMMARY STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT (SESA) Project Team: Mr. P. M. FALL, Transport Engineer, OITC.2 Mr. N. SAMB, Consultant Socio-Economist, OITC.2 Mr. A. KIES, Consultant Economist, OITC 2 Mr. M. KINANE, Principal Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Consultant Environmentalist ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: Mr. Amadou OUMAROU Regional Director: Mr. Jacob KOLSTER Division Manager: Mr. Abayomi BABALOLA 1 PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment Project Name : ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT Country : TUNISIA Project Number : P-TN-DB0-013 Department : OITC Division: OITC.2 1 Introduction This report is a summary of the Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) of the Road Project Modernization Project 1 for improvement works in terms of upgrading and construction of road structures and primary roads of the Tunisian classified road network. This summary has been prepared in compliance with the procedures and operational policies of the African Development Bank through its Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) for Category 1 projects. The project description and rationale are first presented, followed by the legal and institutional framework in the Republic of Tunisia. A brief description of the main environmental conditions is presented, and then the road programme components are presented by their typology and by Governorate. The summary is based on the projected activities and information contained in the 60 EIAs already prepared. It identifies the key issues relating to significant impacts and the types of measures to mitigate them. It is consistent with the Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) developed to that end. -

Les Projets D'assainissement Inscrit S Au Plan De Développement

1 Les Projets d’assainissement inscrit au plan de développement (2016-2020) Arrêtés au 31 octobre 2020 1-LES PRINCIPAUX PROJETS EN CONTINUATION 1-1 Projet d'assainissement des petites et moyennes villes (6 villes : Mornaguia, Sers, Makther, Jerissa, Bouarada et Meknassy) : • Assainissement de la ville de Sers : * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés (mise en eau le 12/08/2016); * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : travaux achevés. - Assainissement de la ville de Bouarada : * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés en 2016. * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : les travaux sont achevés. - Assainissement de la ville de Meknassy * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés en 2016. * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : travaux achevés. • Makther: * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés en 2018. * Travaux complémentaires des réseaux d’assainissement : travaux en cours 85% • Jerissa: * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés et réceptionnés le 12/09/2014 ; * Réseaux d’assainissement : travaux achevés (Réception provisoire le 25/09/2017). • Mornaguia : * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés. * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : travaux achevés Composantes du Reliquat : * Assainissement de la ville de Borj elamri : • Tranche 1 : marché résilié, un nouvel appel d’offres a été lancé, travaux en cours de démarrage. 1 • Tranche2 : les travaux de pose de conduites sont achevés, reste le génie civil de la SP Taoufik et quelques boites de branchement (problème foncier). * Acquisition de 4 centrifugeuses : Fourniture livrée et réceptionnée en date du 19/10/2018 ; * Matériel d’exploitation: Matériel livré et réceptionné ; * Renforcement et réhabilitation du réseau dans la ville de Meknassy : travaux achevés et réceptionnés le 11/02/2019. -

The Situation DREF Final Report Tunisia

DREF final report Tunisia: Civil Unrest DREF operation n° MDRTN004 28 September, 2011 The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of National Societies to respond to disasters. Summary: CHF 150 000 was allocated from the IFRC’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) 25 January, 2011 to support the national society in delivering assistance to some 5000 beneficiaries, or to replenish disaster preparedness stocks. For several months the Tunisian Red Crescent has marked its strong presence in the society by assisting poor families in need and alleviating the suffering of others affected by the events of the revolution that began on December 17, 2010. Throughout Tunisia, volunteers provided moral and material assistance to more than 1000 families mainly in ten cities. Since the Libyan crisis has occurred which took a toll over the Tunisian-Libyan borders, it was not an easy work for the Tunisian Red Crescent Volunteers to handle the effects of the internal unrest and the pressure along the Tunisian-Libyan border . In March 2011, the Tunisian Red Crescent Society distributed food baskets after the civil unrest. TRC The total amount spent was CHF 94,430. The remaining balance of CHF 55,570 will be reimbursed to DREF. The major donors to the DREF are the Irish, Italian, Netherlands and Norwegian governments and ECHO. -

Inventory of Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants of Coastal Mediterranean Cities with More Than 2,000 Inhabitants (2010)

UNEP(DEPI)/MED WG.357/Inf.7 29 March 2011 ENGLISH MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN Meeting of MED POL Focal Points Rhodes (Greece), 25-27 May 2011 INVENTORY OF MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANTS OF COASTAL MEDITERRANEAN CITIES WITH MORE THAN 2,000 INHABITANTS (2010) In cooperation with WHO UNEP/MAP Athens, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .........................................................................................................................1 PART I .........................................................................................................................3 1. ABOUT THE STUDY ..............................................................................................3 1.1 Historical Background of the Study..................................................................3 1.2 Report on the Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants in the Mediterranean Coastal Cities: Methodology and Procedures .........................4 2. MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER IN THE MEDITERRANEAN ....................................6 2.1 Characteristics of Municipal Wastewater in the Mediterranean.......................6 2.2 Impact of Wastewater Discharges to the Marine Environment........................6 2.3 Municipal Wasteater Treatment.......................................................................9 3. RESULTS ACHIEVED ............................................................................................12 3.1 Brief Summary of Data Collection – Constraints and Assumptions.................12 3.2 General Considerations on the Contents -

The Republic of Tunisia Treated Sewage Irrigation Project External Evaluator: Yuriko Sakairi, Yasuhiro Kawabata Sanshu Engineering Consultant Co., Ltd

The Republic of Tunisia Treated Sewage Irrigation Project External Evaluator: Yuriko Sakairi, Yasuhiro Kawabata Sanshu Engineering Consultant Co., Ltd. Field Survey: October 2007–March 2008 1. Project Profile and Japanese ODA Loan Tunis Tunisia Algeria Names of areas targeted in the project (1) Bizerte (2) Menzel Bourguiba (3) Béja (4) Medjez El-Bab (5) Jendouba (6) Nabuel (7) Siliana (8) Msaken (9) Jerba Aghir Libya (10) Médenine Map of the project area Water-saving irrigation drainpipes 1.1 Background Of the total area of 164,154 km2 (about two-fifths the area of Japan) in Tunisia, 38,000 km2 is used to produce agricultural products. The agricultural sector plays an important role in its economy, accounting for around 11% of Tunisia’s domestic national product (GDP) and a third of the working population. However, in Tunisia, which gets very little rainfall, most of the arable land is found in either arid or semi-arid areas, and agricultural regions that rely primarily on rainwater frequently suffer major damage from drought. To stabilize agricultural production and increase crop yields, development of irrigation facilities is indispensable. On the other hand, since surface and groundwater resources are limited, securing enough water for agricultural irrigation is a major challenge, especially in the dry season. Under these circumstances, treated sewage is an important source of relatively stable water supply whether in the rainy season or dry season, and so effective utilization of this water resource was sought. Around 1965, Tunisia began implementing a series of irrigation projects based on the use of treated sewage water for agriculture, and, on the basis of that experience, promoted development plans (including the present project) related to sewage treatment facilities and irrigation facilities. -

Étude Sur La Mise En Œuvre Du Principe De La Discrimination

ÉTUDE SUR LA MISE EN ŒUVRE DU PRINCIPE DE DE PRINCIPE DU ŒUVRE EN MISE LA SUR ÉTUDE LA DISCRIMINATION POSITIVE POUR LA PÉRIODE PÉRIODE LA POUR POSITIVE DISCRIMINATION LA DU PLAN DE DÉVELOPPEMENT QUINQUENNAL QUINQUENNAL DÉVELOPPEMENT DE PLAN DU 2016-2020 CAS DES GOUVERNORATS DE KÉBILI ET DE DE ET KÉBILI DE GOUVERNORATS DES CAS JENDOUBA ÉTUDE SUR LA MISE EN ŒUVRE DU PRINCIPE DE LA DISCRIMINATION POSITIVE POUR LA PÉRIODE DU PLAN DE DÉVELOPPEMENT QUINQUENNAL 2016-2020 CAS DES GOUVERNORATS DE KÉBILI ET DE JENDOUBA MANEL DRIDI Docteur en économie de développement, Enseignante à l’Ecole Supérieure de Commerce de Tunis Laboratoire de recherche « Prospectives, Stratégies et Développement Durable » (Université de Tunis el Manar) En partenariat avec : Tunis, Mars 2021 ÉTUDE SUR LA MISE EN ŒUVRE DU PRINCIPE DE LA DISCRIMINATION POSITIVE POUR LA PÉRIODE DU PLAN DE DÉVELOPPEMENT QUINQUENNAL 2016-2020 CAS DES GOUVERNORATS DE KÉBILI ET DE JENDOUBA MANEL DRIDI Docteur en économie de développement, Enseignante à l’Ecole Supérieure de Commerce de Tunis Laboratoire de recherche « Prospectives, Stratégies et Développement Durable » (Université de Tunis el Manar) Cette étude a été réalisée par Solidar Tunisie en partenariat avec Nomad 08, association Nakhla et association Mawtini Byati dans le cadre du collectif « Pour une gouvernance juste et citoyenne des ressources naturelles », avec l’appui de POMED. En partenariat avec : Tunis, Mars 2021 ÉTUDE SUR LA MISE EN ŒUVRE DU PRINCIPE DE LA DISCRIMINATION POSITIVE POUR LA PÉRIODE DU PLAN DE DÉVELOPPEMENT QUINQUENNAL -

Final Report Volume I Main Report

No. JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE REPUBLIC OF TUNISIA THE DETAILED DESIGN STUDY ON THE RURAL WATER SUPPLY PROJECT IN THE REPUBLIC OF TUNISIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME I MAIN REPORT MARCH 2001 NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. TAIYO CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. S S S CR (5) 01 – 45 ESTIMATE OF PROJECT COST Estimate of Base Cost:As of December 2000 Price Level Currency Exchange rate:US$1.0 = 1.384TD = JP¥114.75 LIST OF VOLUMES VOLUME I MAIN REPORT VOLEME II SUPPORTING REPORT VOLUME III RAPPORT DE CONCEPTION DÉTAILLÉE ARIANA FAIDA EL AMRINE-SIDI GHRIB ARIANA HMAIEM ESSOUFLA ARIANA TYAYRA BEN AROUS OULED BEN MILED-OULED SAAD BEN AROUS SIDI FREDJ NABEUL SIDI HAMMED ZAGHOUAN JIMLA ZAGHOUAN ROUISSAT BOUGARMINE BIZERTE SMADAH BIZERTE TERGULECHE BEJA EL GARIA BEJA EL GARRAG BEJA FATNASSA JENDOUBA CHOUAOULA JENDOUBA COMPLEXE AEP BARBARA LE KEF CHAAMBA-O.EL ASSEL-HMAIDIA LE KEF M’HAFDHIA-GHRAISSIA KAIROUAN CHELALGA KAIROUAN GUDIFETT KAIROUAN HMIDET KAIROUAN ZGAINIA KASSERINE DAAYSIA KASSERINE HENCHIR TOUNSI KASSERINE OUED LAGSAB KASSERINE SIDI HARRATH-GOUASSEM SIDI BOUZID AMAIRIA SIDI BOUZID BLAHDIA SIDI BOUZID BOUCHIHA SIDI BOUZID MAHROUGA MAHDIA COMPLEXE BOUSSLIM MAHDIA COMPLEXE AITHA GAFSA HENCHIR EDHOUAHER GAFSA KHANGUET ZAMMOUR GAFSA THLEIJIA GABÉS BATEN TRAJMA GABÉS CHAABET EJJAYER GABÉS EZZAHRA MEDENINE BOUGUEDDIMA MEDENINE CHOUAMEKH-R.ENNAGUEB MEDENINE ECHGUIGUIA MEDENINE TARF ELLIL VOLUME IV ÉBAUCHE DES DOCUMENTS D’APPEL D’OFFRES GOUVERNORAT ARIANA GOUVERNORAT BEN AROUS GOUVERNORAT -

The Gafsa Mining Basin Between Riots and a Social Movement: Meaning and Significance of a Protest Movement in Ben Ali’S Tunisia Eric Gobe

The Gafsa Mining Basin between Riots and a Social Movement: meaning and significance of a protest movement in Ben Ali’s Tunisia Eric Gobe To cite this version: Eric Gobe. The Gafsa Mining Basin between Riots and a Social Movement: meaning and significance of a protest movement in Ben Ali’s Tunisia. 2010. halshs-00557826 HAL Id: halshs-00557826 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00557826 Preprint submitted on 20 Jan 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Gafsa Mining Basin between Riots and a Social Movement: meaning and significance of a protest movement in Ben Ali’s Tunisia ∗ Eric Gobe Abstract The year 2008 was marked, in Tunisia, by the Revolt of the Gafsa Mining Basin. The social mobilizations which shook this poor area, located close to the Algerian border, represent the most important protest movement seen in Tunisia since the Bread Revolt of January 1984. Within Tunisia’s authoritarian context, this Revolt of the Mining Basin has shown that significant segments of the Tunisian population were able to voice their protest; at the same time, however, the protest movement, due to the limited support it enjoyed within Tunisian society, was unable to grow, nor was it able to withstand the coercive policy of Ben Ali’s regime. -

Historical and Contemporary Perspectives of Water Culture in Tunisia

Historical and contemporary perspectives of water culture in Tunisia Nizar Omrani and Mohamed Ouessar Institut des Régions Arides (IRA), Médenine, Tunisia Summary. Water culture in Tunisia is a secularly tradition. The remnant of many water harvesting and hydraulic structures across the country is a clear indication of the water historical wealth built up by the successive civilizations. Since the antiquity with the Roman period (Zaghouan aqueduct, water temple) passing through the Islamic age (Aghlabit cisterns) until the contemporary water harvesting and storage structures (meskat, jessour, hillside dams and large dams), water mobilization and management was amongst the concern of the societies. At present, modern Tunisia is engaged in holistic strategy for water conservation and management focused on the water demand master. Several projects were undertaken to enhance water distribution efficiency both for domestic and agricultural purposes. This paper addresses the historical review and contemporary perspectives of water culture in Tunisia. Keywords. Water culture – Management – Irrigation – Harvesting - Tunisia. Perspectives historiques et contemporraines de la culture de l’eau en Tunisie Résumé. La culture de l’eau en Tunisie est une tradition séculaire. Les vestiges des ouvrages de collecte des eaux sont distribués dans tout le pays. Ils donnent une preuve indiscutable de l’expertise hydraulique des civilisations qui s’y sont succédées. Depuis l’antiquité avec la période romaine (aqueduc de Zaghouan, temple des eaux) en passant par l’âge islamique (citernes des aghlabites) jusqu’aux structures contemporaines de collecte et stockage des eaux (meskat, jessours, lacs collinaires et grands barrages), la mobilisation des eaux a toujours été la première préoccupation. -

Genome-Wide Insights on Gastrointestinal Nematode

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Genome‑wide insights on gastrointestinal nematode resistance in autochthonous Tunisian sheep A. M. Ahbara1,2, M. Rouatbi3,4, M. Gharbi3,4, M. Rekik1, A. Haile1, B. Rischkowsky1 & J. M. Mwacharo1,5* Gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) infections have negative impacts on animal health, welfare and production. Information from molecular studies can highlight the underlying genetic mechanisms that enhance host resistance to GIN. However, such information often lacks for traditionally managed indigenous livestock. Here, we analysed 600 K single nucleotide polymorphism genotypes of GIN infected and non‑infected traditionally managed autochthonous Tunisian sheep grazing communal natural pastures. Population structure analysis did not fnd genetic diferentiation that is consistent with infection status. However, by contrasting the infected versus non‑infected cohorts using ROH, LR‑GWAS, FST and XP‑EHH, we identifed 35 candidate regions that overlapped between at least two methods. Nineteen regions harboured QTLs for parasite resistance, immune capacity and disease susceptibility and, ten regions harboured QTLs for production (growth) and meat and carcass (fatness and anatomy) traits. The analysis also revealed candidate regions spanning genes enhancing innate immune defence (SLC22A4, SLC22A5, IL‑4, IL‑13), intestinal wound healing/repair (IL‑4, VIL1, CXCR1, CXCR2) and GIN expulsion (IL‑4, IL‑13). Our results suggest that traditionally managed indigenous sheep have evolved multiple strategies that evoke and enhance GIN resistance and developmental stability. They confrm the importance of obtaining information from indigenous sheep to investigate genomic regions of functional signifcance in understanding the architecture of GIN resistance. Small ruminants (sheep and goats) make immense socio-economic and cultural contributions across the globe. -

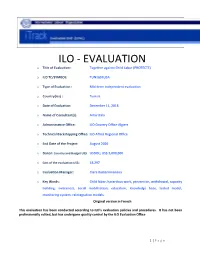

ILO - EVALUATION O Title of Evaluation: Together Against Child Labor (PROTECTE)

ILO - EVALUATION o Title of Evaluation: Together against Child Labor (PROTECTE) o ILO TC/SYMBOL: TUN1602USA o Type of Evaluation : Mid-term independent evaluation o Country(ies) : Tunisia o Date of Evaluation: December 11, 2018 o Name of Consultant(s): Artur Bala o Administrative Office: ILO Country Office-Algiers o Technical Backstopping Office: ILO Africa Regional Office o End Date of the Project: August 2020 o Donor: Country and Budget US$ USDOL; US$ 3,000,000 o Cost of the evaluation US$: 18,297 o Evaluation Manager: Clara Ramaromanana o Key Words: Child labor, hazardous work, prevention, withdrawal, capacity building, awareness, social mobilization, education, knowledge base, tested model, monitoring system, reintegration models. Original version in French This evaluation has been conducted according to ILO’s evaluation policies and procedures. It has not been professionally edited, but has undergone quality control by the ILO Evaluation Office 1 | Page Table of Contents Acronyms....................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 8 2. Project Overview .................................................................................................................... 9 3. -

Tunisia 2020 Crime & Safety Report

Tunisia 2020 Crime & Safety Report This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Embassy in Tunis. OSAC encourages travelers to use this report to gain baseline knowledge of security conditions in Tunisia. For more in-depth information, review OSAC’s Tunisia country page for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. Travel Advisory The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses Tunisia at Level 2, indicating travelers should exercise increased caution due to terrorism. Do not travel to within 30 km of southeastern Tunisia along the border with Libya; mountainous areas in the country’s west, Kasserine, including the Chaambi Mountain National Park area; Jendouba south of Ain Drahem and west of RN15, El Kef, and next to the Algerian border; or Sidi Bou Zid and Gafsa in central Tunisia due to terrorism. Do not travel to the desert south of Remada due to the military zone. Review OSAC’s report, Understanding the Consular Travel Advisory System. Overall Crime and Safety Situation Crime Threats The U.S. Department of State has assessed Tunis as being a LOW-threat location for crime directed at or affecting official U.S. government interests. Reliable crime statistics are difficult to obtain, but violent crime involving the use of firearms (e.g. assault, homicide, armed robbery) is rare. Violent and nonviolent crime (e.g. personal robberies, residential break-ins, financial scams, vehicle thefts, petty drug offenses) occurs in Tunis and other large/tourist cities.