Status of Gram and Constraints in Its Cultivation in Churu District of Rajasthan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief Industrial Profile of Hanumangarh District

lR;eso t;rs lR;eso t;rs Brief Industrial Profile of Hanumangarh District Carried out by MSME-Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Phone : 0141-2213099 ,2212098,2215847 Fax: 0141-2210533 e-mail: [email protected] Web : www.msmedijaipur.gov.in Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 4 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 5 1.2 Topography 5 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 5-6 1.4 Forest 6 1.5 Administrative set up 7 2. District at a glance 7-11 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District -------- 11 3. Industrial Scenario Of --------- 11 3.1 Industry at a Glance 12 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 12 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In 13 The District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 13 3.5 Major Exportable Item 13 3.6 Growth Trend 14 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 14 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 14 3.8.1 List of the units in ------ & near by Area 14 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 14 3.9 Service Enterprises 14 3.9.1 Potentials areas for service industry 14 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 14-15 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 15 4.1 Detail Of Major Clusters 15 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 15 4.1.2 Service Sector 15 4.2 Details of Identified cluster 16 4.2.1 Leather Footwear 16 4.2.2 Plats of Paris 17 5. -

A CASE STUDY of SIKAR, RAJASTHAN Manisha

Journal of Global Resources Volume 4 (01) January 2018 Page 133-137 ISSN: 2395-3160 (Print), 2455-2445 (Online) 20 STRATEGIC PLANS FOR INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT AND ITS POTENTIAL: A CASE STUDY OF SIKAR, RAJASTHAN Manisha Sharma 1and M. A. Khan 2 1 Head, Dept. of Geography. B.D. Todi College, Lachhmangarh (Sikar), India 2Deputy Director, Department of Minority Affairs, GoR, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India Abstract: Industrial Potential means anything that may be a possibility; potentially and existing in possibility, not in actuality and being potent. Industrial or economic potential is determined by the quantity of labor resources and the quality of their vocational training by the volume of production capacities of Industrial and construction organizations, by the production capacities of agriculture, by the extent of transportation arteries, by the development of sectors in the non-production sphere by advances in science and technology and by the resources of explored mineral deposits. Resources have the most vital role in the development of a region. The main resources of study area which have great significance for industrial development are minerals, agriculture and livestock. Water and electricity provides basis for Industrial development. However, the area has good potential for agro based, mineral based and livestock based industries. As Sikar enjoys the benefits of surplus agricultural production and large number of livestock, it would be worthwhile to propose few agro based and livestock industrial units. Limestone is also being exploited so, there is scope of cement and others industries. This paper describes a strategic plan for development of Industries and its potential in Sikar district. -

Research Article IMPACT of FORMAL CREDIT on AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT in the RAJASTHAN

International Journal of Agriculture Sciences ISSN: 0975-3710&E-ISSN: 0975-9107, Volume 9, Issue 5, 2017, pp.-3763-3766. Available online at http://www.bioinfopublication.org/jouarchive.php?opt=&jouid=BPJ0000217 Research Article IMPACT OF FORMAL CREDIT ON AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE RAJASTHAN KUMAWAT RAJU1*, SINGH N.K.1 AND PRAMENDRA2* 1Department of Agricultural Economics, College of Agriculture, Swami Keshwanand Rajasthan Agricultural University, Bikaner, 334006, Rajasthan 2Department of Agricultural Economics & Management, RCA, Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology, Udaipur, 313001, Rajasthan *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: January 09, 2017; Revised: January 16, 2017; Accepted: January 17, 2017; Published: January 30, 2017 Abstract- The present study was conducted to analyse the impact of agricultural credit on agricultural development and constraints in advancing the agricultural credit. The study was conducted in the district of Bikaner region viz., Sriganganagar, Hanumangarh, Bikaner and Churu district. A lead bank of each selected district was selected purposively for collection of secondary and primary data in respect of agricultural loan supplied to the farmers. A sample of 30 farmers was drawn as borrower farmers from each selected district by probability proportion to the number of borrower farmers. The increasing trend was observed in the value of net worth with increase in farm size on both borrower and non-borrower farmers of the study area. At overall level about 47 to 50 per cent net worth value was higher on borrower farmers than the non-borrower farmers. The value of current assets was ranged from 1.81 to 3.82 on borrower farmers in comparison to non-borrower farmers 1.02 to 2.90. -

District Census Handbook, Churu, Rajasthan and Ajmer

CENSUS, 195 1 RAJASTHAN AND AJMER DISTRICT CERUS' ,HANDBOOK CHURU PART .-GENERAL DESCRIPTION AND CENSUS TABLES By Pt. YAMUNA LAL DASHORA, B.A., LL.B., Superintendent of Censl1s Operations, Rajasthan and Aimer. JODHPUR: P.RINTED AT THE GOVE]1};llENT PRESS 1956 1f.R:EFAcE, .... ,:, . - , 'The "CensuA Reports' ill' .qlq.en -·times :were printed one for the whole Province. of Ra.j putana and.another for A-jIl1:er-:Merwara._"Soin~ of the Principal 8tates now merged in Rajasthan published 'their own reports. This time the -State Census H eports have been published in the following volumes:- 1. Part I A .. Report. 2. Part 1--B .. ~ubsidiary Tables and District Index of Non-Agricultural Occupations. 3. Part I -C .. Appendices. 4. Part U-A .. r::eneral Population Tables, Household and Age Sample Tables, Social and Cultural Tables, Table E Summary Figures by Administrative Units, and Local 'KA' Infirmities. 5. Part II-B .. Economic Tables. They contain statistics down to the district level The idea of preparing the District Census Handbook separately for each district was put forward .by' Shri R. A. GopaJaswami. I. C. R., Registrar General. India, and ex-officio Census' Commissioner of' India, as part of a plan intended to secu~e an effective, method of preserving the census records prepared for areas below the qistrict level. 'He proposed that all the district, census tables and census abstracts prepared during the process of sorting and cOinpilatiori should be bound together in a single manuscript volume, called the District Census Handbook, and suggested to the State Governments that the Handbook (with or without the addition of other useful information relating to the district) should be printed and pub lished at their own cost in the same manner as the village statistics in the past. -

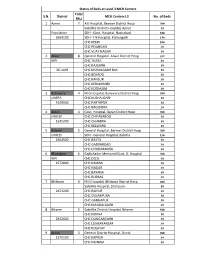

Status of Beds at Level 3 MCH Centers Total S.N

Status of Beds at Level 3 MCH Centers Total S.N. District MCH Centers L3 No. of Beds FRU 1 Ajmer 7 A K Hospital, Beawer District Hosp 300 Satellite District Hospital, Ajmer 30 Population SDH - Govt. Hospital, Nasirabad 100 2664100 SDH- Y N Hospital, Kishangarh 150 CHC KEKRI 100 CHC PISANGAN 30 CHC VIJAY NAGAR 30 2 Alwar 8 General Hospital, Alwar District Hosp 332 NIPI CHC TIJARA 30 CHC RAJGARH 50 36 LAKH CHC KISHANGARH BAS 50 CHC BEHROD 50 CHC BANSUR 30 CHC KERLIMANDI 30 CHC KOTKASIM 30 3 Banswara 4 M G Hospital, Banswara District Hosp 300 UNFPA CHC KUSHALGARH 50 1629900 CHC PARTAPUR 30 CHC BAGIDORA 30 4 Baran 4 Govt. Hospital, Baran District Hosp 300 UNICEF CHC CHIPABAROD 30 1245200 CHC CHHABRA 50 CHC KELWARA 30 5 Barmer 5 General Hospital, Barmer District Hosp 200 UNICEF SDH - General Hospital, Balotra 150 2404500 CHC BAYTU 30 CHC GADRAROAD 30 CHC DHORIMANNA 30 6 Bharatpur 6 RajBahadur Memorial Govt. D. Hospital 300 NIPI CHC DEEG 50 2572800 CHC KAMAN 30 CHC NAGAR 30 CHC BAYANA 50 CHC RUPBAS 30 7 Bhilwara 6 M G Hospital, Bhilwara District Hosp 400 Satellite Hospital, Shahpura 50 2453200 CHC RAIPUR 30 CHC GULABPURA 50 CHC GANGAPUR 50 CHC MANDALGARH 50 8 Bikaner 5 Satellite District Hospital, Bikaner 100 CHC NOKHA 50 2322600 CHC DUNGARGARH 30 CHC LUNKARANSAR 30 CHC KOLAYAT 30 9 Bundi 3 General District Hospital, Bundi 300 1170100 CHC KAPREN 30 CHC NAINWA 50 Total S.N. District MCH Centers L3 No. of Beds FRU 10 Chittorgarh 5 District Hospital, Chittorgarh 300 1629900 CHC BEGUN 50 CHC KAPASAN 50 CHC BADISADRI 50 CHC NIMBAHERA 100 11 Churu 5 D B Hospital, Churu District Hospital 225 2059300 SDH - S R J Hospital, Ratangarh 100 SDH - S B Hospital, Sujangarh 100 CHC RAJGARH 50 CHC SARDARSHAHAR 75 12 Dausa 3 District Hospital, Dausa 150 NIPI CHC LALSOT 30 1606100 CHC MAHUWA 30 13 Dholpur 4 Sadar District Hospital, Dholpur 300 1196300 CHC RAJAKHERA 30 CHC BARI 50 CHC BASERI 30 14 Dungarpur 4 General District Hospital, Dungarpur 300 UNICEF SDH - Govt. -

Final Population Figures, Series-18, Rajasthan

PAPER 1 OF 1982 CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES 18 RAJASTHAN fINAL POPULATION FIGU~ES (TOTAL POPULATION, SCHEDULED CASTE POPULATION AND .sCHEDULED TRIBE POPULATION) I. C. SRIVASTAVA ·1)f the Indian Administrative Service Director of Census Operations Rajasthan INTRODUCfION The final figures of total population, scheduled caste and scheduled tribe population of Rajasthan Stat~ are now ready for release at State/District/Town and Tehsil levels. This Primary Census Abs tract, as it is called, as against the provisional figures contained in our three publications viz. Paper I, fFacts & Figures' and Supplement to Paper-I has been prepared through manual tabulation by over 1400 census officials including Tabulators, Checkers and Supervisors whose constant and sustained efforts spread over twelve months enabled the Directorate to complete the work as per the schedule prescribed at the national level. As it will take a few months more to publish the final population figures at the viJ1age as well as ward levels in towns in the form of District Census Handbooks, it is hoped, this paper will meet the most essential and immediate demands of various Government departments, autonomous bodies, Cor porations, Universities and rtsearch institutions in relation to salient popUlation statistics of the State. In respect of 11 cities with One lac or more population, it has also been possible to present ~the data by municipal wards as shown in Annexure. With compliments from Director of Census Operations, Rajasthan CONTENTS INTRODUCTION (iii) Total Population, Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribt' Population by Districts, 1981 Total Schedu1ed Caste and Scheduled Tribe Population. ( vi) 1. Ganganagar District 1 2. -

List of Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Office Bearers-2017

List of Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Office bearers-2017 Chief Organiser 1 Shri Rakesh Pareek Shri Rakesh Pareek Chief Organiser Chief Organiser Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal B-613 Sawai Jaisingh Highway, Vill/PO-Sarvad Ganeshganj Banipark Ajmer Jaipur Rajasthan Rajasthan Tel-09414419400 Mahila Organiser 1 Smt. Kalpana Bhatnagar Mahila Organiser Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal 46, Navrang Nagar Beawar, Dist- Ajmer Rajasthan Tel: 09001864018 Additional Chief OrganisersP 1 Shri Hajari Lal Nagar 2 Shri Ram Kishan Sharma Additional Chief Organiser Additional Chief Organiser Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal C 4/272 Vidyadhar Nagar Ghanshyam Ji Ka Mandir Jaipur (Rajasthan) Gangapol Bahar, Badanpura Tel:- 09214046342, 09414446342 Jaipur 09829783637 Rajasthan Tel:- 09314504631 3 Shri Hulas Chand Bhutara 4 Shri Manjoor Ahmed Additional Chief Organiser Additional Chief Organiser Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal C-53, Panchshel Colony 4354, Mohalla Kayamkhani Purani Chungi Topkhano Ka Rasta Ajmer Road Chandpol Bazar Jaipur--302019 Jaipur Rajasthan Rajasthan Tel: 01531-220642, 09414147159 Tel: 09314603489, 08890473767 09079004827 5 Shri Bhawani Mal Ajmera 6 Shri Ram Bharosi Saini Additional Chief Organiser Additional Chief Organiser Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Rahul Electricals, V/Post- Chantali Ganesh Shopping Teh- Wair Complex, Opp.R No-2, Dist- Bharatpur VKI Chonu Rd. Rajasthan -

Stdy Rgeco.Pdf

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Regional economic inequalities are generally an outcome of uneven distribution of physical and natural resources. Sometimes disparities in the levels of performance also emanate from lack of technical know-how, low level of human development, social inhibitions and virtual absence of initiatives on the part of those who govern the destiny of people. A good number of studies have been undertaken in India and outside which focus on the existing state of inequalities. While some studies attempt to measure inequalities among different countries, others analyse inter-regional or inter-state inequalities. Generally, these studies are based on secondary data, and tend to measure the existing level of inequalities. But very few researchers have enquired into the factors responsible for such disparities. Rajasthan is a developing state of the Indian sub continent, where Mother Nature has not been kind enough to provide a rich endowment of physical and natural resources. Notwithstanding a peaceful political environment and a rich heritage of Marwari entrepreneurship, the State has not registered a very high level of growth in agriculture and industries. Infrastructure development and conservation of scarce water resources have generally received a low priority in the process of planned development. The present study selected 97 indicators pertaining to 12 sectors. A simple weighted average of scores was used to rank 32 districts of the State according to the nature of their relationship with development. Such ranking was done first for each sector, and then a composite rank for all the indicators was assigned to each district. One novel experiment undertaken in this study was to rank the districts on the basis of allocation of plan outlays over the period 1993-2001. -

Tables, Part II-A, Vol-X, Rajasthan and Ajmer

CENSUS OF INDIA 1951 VOLUME X RAJASTHAN AND AJMER PART II A TABLES By Pt. YAMUNA LAL DASHORA B. A., LL. B., Superintendent of Census, Operations. Rajasthan and Ajmer. JODHPUR: PRINTED AT THE GOVERNMENT PREBS. 1953. [PJLleE.Ba. 5/-) THE CENSUS PUBLICATIONS. The Uensus Publications for Rajasthan and Ajmer will consist of the following volumes. .All volumes will be of uniform size, demy quarto 81 X Hi" with the exception of District ..census Handbooks and Primary Census Abstrac~which will be of F'cap size:- 1. Part l-A:-Main Report (narrative) containing six chapters in addition to an Introduction. 422 pages. 2. Part I-B: -- Subsidiary Tables & District Index of Non-agricultural Occupa.tions. Over 450 pages. 3. Part I-C:-Appendices. 210 pages. 4. Part II-A:-Tables other than Economic Tables. 461 pages. 5. Part II-B:-Economic T%bles. 323 pages. 6. District Census Handbooks one for each District in Rajasthan and one for Ajmer State as a whole. Each volume contains (1) an Introductory essay giving a brief description of the district, (2) a review of population figures, (3) District . Census Data at a glance, (4) District Tables, and (5) Primary Census Abstract or Village Directory which gives the code number of every village, its name, area, total population, number of houses, number of literates and population classified into eight livelihood classes. It also shows the distance of railway station, police post, school, hospital etc. In all there will be 26 volumes. 7. Primary Census Abstract or Village Directory tehsilwise, bound separately, tor each district containing the same information as in the Village Directory of Distriot Census Handbooks. -

Rajasthan Urban Sector Development Investment Program: Churu Road Subproject

Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Draft Project Number: 40031-053 May 2014 IND: Rajasthan Urban Sector Development Investment Program - Churu Road Subproject Prepared by Local Self Government Department For the Government of Rajasthan Rajasthan Urban Infrastructure Development Project The initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. ABBREVIATION ADB - Asian Development Bank DSC - Design and Supervision Consultancy EA - Executing Agency EAC - Expert Appraisal Committee FI - Financial Intermediary GLSR - Ground Level Service Reservoir GoI - Government of India GoR - Government of Rajasthan GSI - Geological Survey of India IA - Implementing Agency IEE - Initial Environmental Examination IPMC - Investment Programme Management Consultancy IPMU - Investment Programme Management Unit JNNURM - Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission LSGD - Local Self-Government Department MFF - Multitranche Financing Facility MoEF - Ministry of Environment and Forests NAAQS - National Ambient Air Quality Standards OD - Outer Diameter OHSR - Over Head Service Reservoir OM - Operations Manual PHED - Public Health Engineering Department PMU - Project Management Unit RCC - Reinforced Cement Concrete ROW - Right of Way RPCB - Rajasthan State Pollution Control Board RSPM - Respirable Suspended Particulate Matter RUIDP - Rajasthan Urban Infrastructure Development Project RUSDIP - -

Directorate of Economics & Statistics, Rajasthan, Jaipur

DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS, RAJASTHAN, JAIPUR lR;eso t;rs BASIC STATISTICS RAJASTHAN 2007 DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS RAJASTHAN, JAIPUR PREFACE The Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Rajasthan is publishing statistical book as a basic source of information for the state of Rajasthan since 1956 with the title “BASIC STATISTICS.” The present issue, Basic Statistics- 2007 includes information relating to various socio-economic and developmental activities as provided by different State Government Departments / Boards / Corporations / Commissions etc. We on our part are constantly endeavoring to make the publication a ready reference book by incorporating latest information and extending its coverage. The data presented in this issue relates to the calendar year 2006 or the financial/agriculture/ co-operative year 2005-06 except where otherwise indicated. I am sure that the present issue of the publication, like its previous issues, will be of immense use not only to planners, policy makers and departments implementing developmental programmes but also to research scholars in understanding the socio-economic changes, in all dimensions, taking place in the state. The co-operation extended by various Departments/Agencies in furnishing the required data are appreciated. Besides, my appreciation also goes to the staff of coordination unit for their sincere efforts in bringing out this publication. Suggestions for improvement in coverage and presentation of this publication are welcome. ( Leela Bhatnagar ) Director cum Dy.Secretary, JAIPUR Economics & Statistics, August, 2008 Rajasthan, Jaipur OFFICERS AND OFFICIALS ASSOCIATED WITH THIS PUBLICATION Deputy Director Shri R. K. Pandey Statistical Officer Shri P.C. Jain Statistical Assistant Shri MANOJ SHARMA Smt. Asha Agarwal Smt. -

Study of Phytodiversity of Sikar District of Rajasthan

P: ISSN NO.: 2321-290X RNI : UPBIL/2013/55327 SHRINKHALA : VOL-II * ISSUE-II*October-2014 E: ISSN NO.: 2349 – 980X Study of Phytodiversity of Sikar District of Rajasthan Abstract The present paper deals with the phytodiversity of Sikar district, based on floristic exploration during the period of 2010-2012. In this work, a total number of 355 species belonging to 246 genera and 80 families of 4 different groups of phytodiversity viz. algae(1), pteridophytes(2),gymnosperm (1) and angiosperms (76) were recorded. Out of total 355 species, 351 species of angiosperms belonging to 242 genera were recorded. Keyword: Phytodiversity, Sikar, Rajasthan. Introduction The district is located in the north-eastern part of the state of Rajasthan. It is bounded on the north by Jhunjhunu district, in the north- west by Churu district, in the south-west by Nagaur district in the south- east by Jaipur district. It also touches Mahendragarh district of Haryana. 2 The district has an area of 7742.44 km , and population of 26, 77, 737 (2011 census). Sikar, Churu district and Jhunjhunu district comprise the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan at 27°13’ N 28°.07’ E/27.21° N 28.12°E. Rashmi Vyas During the recent years Indian botanists have emphasized for intensive exploration and compilation of inventories of plants resources of the Research Associate, country. These inventories will also be helpful in compilation of state and Department of Botany, National flora. Govt Dungar P.G. College, In order to achieve the above objectives, district flora for the Bikaner, Rajasthan. state of Rajasthan has been initiated.