Harappan Civilization: Emerging Picture in Hanumangarh District, Rajasthan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Level Sustainable Livestock Production Index: Tool for Livestock Development Planning in Rajasthan

Ind. Jn. of Agri. Eco. Vol.67, No.2, April.-June, 2012 ARTICLES District Level Sustainable Livestock Production Index: Tool for Livestock Development Planning in Rajasthan Prem Chand and Smita Sirohi* I INTRODUCTION Since the past two decades, the concept of sustainability has increasingly occupied the centre stage for the development of the agriculture and allied sectors. With the manifestation of stagnating or declining productivity levels, widening regional disparities and the emergence of environmental externalities, the concerns emerged that development process should be sustainable, i.e., it should be environmentally non-degrading, technically appropriate, economically viable and socially acceptable (FAO, 1991). Before targeting the policy interventions to maintain/enhance the sustainability of a crop or livestock production system, it is imperative to examine whether or not certain necessary conditions essential for sustainable development are present in a given region or ecosystem. The major approaches used in the literature to assess the sustainability of a biological production system in a particular region include, estimation of total factor productivity (Ehui and Spencer, 1990; Rosegrant and Evenson, 1995; Kumar and Mittal, 2006), computation of composite indices covering varied dimensions of sustainability (Saleth and Swaminathan, 1992; Yadav and Rai, 2001; Calker et al., 2004; Sen and Hatai, 2007; Singh and Hiremath, 2010) and Response-Inducing Sustainability Evaluation (RISE) (Hani et al., 2003). While each of these techniques has its own utility, the indexing approach provides a simple practical tool for indicating a set of projects and policies that can be implemented to address the problem areas that impede sustainability. In India, the empirical application of indexing approach has been made in the context of livelihood security, focusing on the ecological and economic dimensions related to crop production. -

Rajasthan List.Pdf

Interview List for Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Rajasthan Date Of Area Of S.No Name Category Father's Name Address Enrol. No. & Date App'n Practice Village Lodipura Post Kamal Kumar Sawai Madho Lal R/2917/2003 1 Obc 01.05.18 Khatupura ,Sawai Gurjar Madhopur Gurjar Dt.28.12.03 Madhopur,Rajasthan Village Sukhwas Post Allapur Chhotu Lal Sawai Laddu Lal R/1600/2004 2 Obc 01.05.18 Tehsil Khandar,Sawai Gurjar Madhopur Gurjar Dt.02.10.04 Madhopur,Rajasthan Sindhu Farm Villahe Bilwadi Ram Karan R/910/2007 3 Obc 01.05.18 Shahpura Suraj Mal Tehsil Sindhu Dt.22.04.07 Viratnagar,Jaipur,Rajasthan Opposite 5-Kha H.B.C. Sanjay Nagar Bhatta Basti R/1404/2004 4 Abdul Kayam Gen 02.05.18 Jaipur Bafati Khan Shastri Dt.02.10.04 Nagar,Jaipur,Rajasthan Jajoria Bhawan Village- Parveen Kumar Ram Gopal Keshopura Post- Vaishali R/857/2008 5 Sc 04.05.18 Jaipur Jajoria Jajoria Nagar Ajmer Dt.28.06.08 Road,Jaipur,Rajasthan Kailash Vakil Colony Court Road Devendra R/3850/2007 6 Obc 08.05.18 Mandalgarh Chandra Mandalgarh,Bhilwara,Rajast Kumar Tamboli Dt.16.12.07 Tamboli han Bhagwan Sahya Ward No 17 Viratnagar R/153/1996 7 Mamraj Saini Obc 03.05.18 Viratnagar Saini ,Jaipur,Rajasthan Dt.09.03.96 156 Luharo Ka Mohalla R/100/1997 8 Anwar Ahmed Gen 04.05.18 Jaipur Bashir Ahmed Sambhar Dt.31.01.97 Lake,Jaipur,Rajasthan B-1048-49 Sanjay Nagar Mohammad Near 17 No Bus Stand Bhatta R/1812/2005 9 Obc 04.05.18 Jaipur Abrar Hussain Salim Basti Shastri Dt.01.10.05 Nagar,Jaipur,Rajasthan Vill Bislan Post Suratpura R/651/2008 10 Vijay Singh Obc 04.05.18 Rajgarh Dayanand Teh Dt.05.04.08 Rajgarh,Churu,Rajasthan Late Devki Plot No-411 Tara Nagar-A R/41/2002 11 Rajesh Sharma Gen 05.05.18 Jaipur Nandan Jhotwara,Jaipur,Rajasthan Dt.12.01.02 Sharma Opp Bus Stand Near Hanuman Ji Temple Ramanand Hanumangar Rameshwar Lal R/29/2002 12 Gen 05.05.18 Hanumangarh Sharma h Sharma Dt.17.01.02 Town,Hanumangarh,Rajasth an Ward No 23 New Abadi Street No 17 Fatehgarh Hanumangar Gangabishan R/3511/2010 13 Om Prakash Obc 07.05.18 Moad Hanumangarh h Bishnoi Dt.14.08.10 Town,Hanumangarh,Rajasth an P.No. -

Brief Industrial Profile of Hanumangarh District

lR;eso t;rs lR;eso t;rs Brief Industrial Profile of Hanumangarh District Carried out by MSME-Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Phone : 0141-2213099 ,2212098,2215847 Fax: 0141-2210533 e-mail: [email protected] Web : www.msmedijaipur.gov.in Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 4 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 5 1.2 Topography 5 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 5-6 1.4 Forest 6 1.5 Administrative set up 7 2. District at a glance 7-11 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District -------- 11 3. Industrial Scenario Of --------- 11 3.1 Industry at a Glance 12 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 12 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In 13 The District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 13 3.5 Major Exportable Item 13 3.6 Growth Trend 14 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 14 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 14 3.8.1 List of the units in ------ & near by Area 14 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 14 3.9 Service Enterprises 14 3.9.1 Potentials areas for service industry 14 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 14-15 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 15 4.1 Detail Of Major Clusters 15 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 15 4.1.2 Service Sector 15 4.2 Details of Identified cluster 16 4.2.1 Leather Footwear 16 4.2.2 Plats of Paris 17 5. -

Regional Study of Variation in Cropping and Irrigation Intensity in Rajasthan State, India

Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research, (ISSN: 0719-3726)(2017), 5(4): 98-105 98 http://dx.doi.org/10.7770/safer-V5N4-art1314 REGIONAL STUDY OF VARIATION IN CROPPING AND IRRIGATION INTENSITY IN RAJASTHAN STATE, INDIA. ESTUDIO REGIONAL DE LA VARIACION DE LA INTENSIDAD DE IRRIGACION Y AGRICULTURA EN EL ESTADO DE RAJASTAN, INDIA. Arjun Lal Meena1 and Priyanka Bisht2 1- Assistant Professor, Department of Geography, Jai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India. Email: [email protected] 2- Research Scholar, Department of Geography, Jai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India. Email: [email protected] Submitted: 05th November 2017; Accepted: 12th December, 2017. ABSTRACT Agriculture is the primary activity which directly or indirectly influences the other activities. It plays a vital role to achieve the self-sufficiency in each sector of economy. Irrigation plays a crucial role in farming for those areas suffering from irregular pattern of rainfall. Rajasthan is the state of India which usually faces the drought condition as the monsoon gets fall. The farming in this state totally depends on the irrigation. This paper includes the district-wise distribution of cropping intensity and irrigation intensity including the comparison of 2013-2014 with the year 2006- 2007. Key words: Irrigation Intensity, Cropping Intensity, Net Area, Gross Area. RESUMEN La agricultura es una actividad primeria la cual está directa o indirectamente relacionada con otras actividades. Esta tiene un rol vital en la autosustentabilidad en cada sector de la economía. La irrigación tiene un rol importante en las granjas de Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research, (ISSN: 0719-3726)(2017), 5(4): 98-105 99 http://dx.doi.org/10.7770/safer-V5N4-art1314 estas áreas y tiene un patrón irregular debido a las lluvias. -

Rajasthan Result.Pdf

F.No. N-15011/43/2018-DLA (N) Government of India Ministry of Law and Justice Department of Legal Affairs Notary Cell ***** Notary Cell, Department of Legal Affairs had conducted Interviews for appointment as notaries for the State of Rajasthan from 23.05.2018 to 30.05.2018 at Jaipur. The candidates were assessed keeping in view their competency, legal knowledge and other relevant factors related to the selection of Notary as per requirement of the Notaries Act, 1952, the Notaries Rules, 1956 and the relevant guidelines by the Interview Board constituted for the purpose by the Central Government. On the basis of the performance of the candidates before the Interview Board, the Interview Board has recommended names of the following candidates for appointment as notaries for the State of Rajasthan. 2. All the successful candidates, whose names appear in the below mentioned list, will be issued Appointment Letters for appointment as Notary. The candidates may contact for enquires Notary Cell on Tel. No. 011-23383221 between 3 P.M. to 4 P.M. The candidates are strictly advised not to visit this Office personally. 3. All the recommended candidates are required to submit following documents:- (i) No Objection Certificate from Bar Council of the concerned State. (ii) Bank Demand Draft of Rs.2,000/- in favour of Pay & Accounts Officer, Department of Legal Affairs, New Delhi by Speed Post OR Registered Post only within a period of 30 days of issue of appointment letters. (iii) The candidates are also required to submit any other document which has not been submitted by the candidate at the time of Interview and asked him/her to submit afterwards. -

A CASE STUDY of SIKAR, RAJASTHAN Manisha

Journal of Global Resources Volume 4 (01) January 2018 Page 133-137 ISSN: 2395-3160 (Print), 2455-2445 (Online) 20 STRATEGIC PLANS FOR INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT AND ITS POTENTIAL: A CASE STUDY OF SIKAR, RAJASTHAN Manisha Sharma 1and M. A. Khan 2 1 Head, Dept. of Geography. B.D. Todi College, Lachhmangarh (Sikar), India 2Deputy Director, Department of Minority Affairs, GoR, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India Abstract: Industrial Potential means anything that may be a possibility; potentially and existing in possibility, not in actuality and being potent. Industrial or economic potential is determined by the quantity of labor resources and the quality of their vocational training by the volume of production capacities of Industrial and construction organizations, by the production capacities of agriculture, by the extent of transportation arteries, by the development of sectors in the non-production sphere by advances in science and technology and by the resources of explored mineral deposits. Resources have the most vital role in the development of a region. The main resources of study area which have great significance for industrial development are minerals, agriculture and livestock. Water and electricity provides basis for Industrial development. However, the area has good potential for agro based, mineral based and livestock based industries. As Sikar enjoys the benefits of surplus agricultural production and large number of livestock, it would be worthwhile to propose few agro based and livestock industrial units. Limestone is also being exploited so, there is scope of cement and others industries. This paper describes a strategic plan for development of Industries and its potential in Sikar district. -

Sarasvati Civilization, Script and Veda Culture Continuum of Tin-Bronze Revolution

Sarasvati Civilization, script and Veda culture continuum of Tin-Bronze Revolution The monograph is presented in the following sections: Introduction including Abstract Section 1. Tantra yukti deciphers Indus Script Section 2. Momentous discovery of Soma samsthā yāga on Vedic River Sarasvati Basin Section 3. Binjor seal Section 4. Bhāratīya itihāsa, Indus Script hypertexts signify metalwork wealth-creation by Nāga-s in paṭṭaḍa ‘smithy’ = phaḍa फड ‘manufactory, company, guild, public office, keeper of all accounts, registers’ Section 5. Gaṇeśa pratimā, Gardez, Afghanistan is an Indus Script hypertext to signify Superintendent of phaḍa ‘metala manufactory’ Section 6. Note on the cobra hoods of Daimabad chariot Section 7 Note on Mohenjo-daro seal m0304: phaḍā ‘metals manufactory’ Section 8. Conclusion Introduction The locus of Veda culture and Sarasvati Civilization is framed by the Himalayan ranges and the Indian Ocean. 1 The Himalayan range stretches from Hanoi, Vietnam to Teheran, Iran and defines the Ancient Maritime Tin Route of the Indian Ocean – āsetu himācalam, ‘from the Setu to Himalayaś. Over several millennia, the Great Water Tower of frozen glacial waters nurtures over 3 billion people. The rnge is still growing, is dynamic because of plate tectonics of Indian plate juttng into and pushing up the Eurasian plate. This dynamic explains river migrations and consequent desiccation of the Vedic River Sarasvati in northwestern Bhāratam. Intermediation of the maritime tin trade through the Indian Ocean and waterways of Rivers Mekong, Irrawaddy, Salween, Ganga, Sarasvati, Sindhu, Persian Gulf, Tigris-Euphrates, the Mediterranean is done by ancient Meluhha (mleccha) artisans and traders, the Bhāratam Janam celebrated by R̥ ṣi Viśvāmitra in R̥ gveda (RV 3.53.12). -

District Boundary Assembly Constituency

NEW ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES (Based on Rajasthan Gazette Notification SADULSHAHAR-1 Dated 25th January, 2006) GANGANAGAR-2 SANGARIA-7 KARANPUR-3 RAJASTHAN PILIBANGA (SC)-9 HANUMANGARH- 8 GANGANAGAR RAISINGHNAGAR (SC)-5 SURATGARH-4 HANUMANGARH BHADRA-11 NOHAR-10 ® ANUPGARH (SC)-6 TARANAGAR-20 LUNKARANSAR-16 SADULPUR-19 KHAJUWALA SARDARSHAHAR-21 (SC)-12 CHURU PILANI CHURU-22 (SC)-25 BIKANER MANDAWA-28 SURAJGARH-26 JHUNJHUNUN-27 TIJARA-59 JHUNJHUNUN DUNGARGARH-17 BIKANER FATEHPUR-32 WEST-13 KHETRI-31 BEHROR- BIKANER RATANGARH-23 EAST-14 NAWALGARH- 62 MUNDAWAR- 61 29 KISHANGARH KOLAYAT-15 UDAIPURWATI- BAS-60 LACHHMANGARH-33 30 NEEM KA THANA-38 KAMAN-70 SUJANGARH KOTPUTLI-40 (SC)-24 SIKAR-35 BANSUR-63 KHANDELA-37 ALWAR LADNUN- URBAN-66 RAMGARH-67 NOKHA-18 106 DHOD (SC)-34 SIKAR SRIMADHOPUR-39 ALWAR NAGAR-71 ALWAR VIRATNAGAR-41 RURAL (SC)-65 DEEG - DANTA KUMHER-72 RAMGARH-36 KATHUMAR DEEDWANA-107 SHAHPURA-42 PHALODI-122 (SC)-69 JAYAL RAJGARH - (SC)-108 BHARATPUR- NAGAUR- CHOMU-43 THANAGAZI-64 LAXMANGARH (ST)-68 73 109 NADBAI-74 NAWAN- JAISALMER- 115 JAMWA BHARATPUR 132 AMBER-47 MAHUWA-86 NAGAUR MAKRANA- RAMGARH BANDIKUI-85 WEIR 113 (ST)-48 (SC)-75 JAISALMER KHINVSAR-110 JHOTWARA-46 JAIPUR DAUSA- LOHAWAT-123 BAYANA POKARAN- ADARSH 88 NAGAR-53 DAUSA (SC)-76 133 PHULERA-44 SIKRAI RAJAKHERA-80 DEGANA- (SC)-87 HINDAUN 112 PARBATSAR- BASSI (SC)-82 BAGRU 114 (ST)-57 PUSHKAR- (SC)-56 TODABHIM DHOLPUR- JODHPUR 99 (ST)-81 DHAULPUR 79 OSIAN- DUDU BARI-78 125 (SC)-45 CHAKSU KARAULI-83 MERTA (SC)-58 LALSOT BAMANWAS BASERI BHOPALGARH (SC)-111 (ST)-89 (SC)-126 -

Research Article IMPACT of FORMAL CREDIT on AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT in the RAJASTHAN

International Journal of Agriculture Sciences ISSN: 0975-3710&E-ISSN: 0975-9107, Volume 9, Issue 5, 2017, pp.-3763-3766. Available online at http://www.bioinfopublication.org/jouarchive.php?opt=&jouid=BPJ0000217 Research Article IMPACT OF FORMAL CREDIT ON AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE RAJASTHAN KUMAWAT RAJU1*, SINGH N.K.1 AND PRAMENDRA2* 1Department of Agricultural Economics, College of Agriculture, Swami Keshwanand Rajasthan Agricultural University, Bikaner, 334006, Rajasthan 2Department of Agricultural Economics & Management, RCA, Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology, Udaipur, 313001, Rajasthan *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: January 09, 2017; Revised: January 16, 2017; Accepted: January 17, 2017; Published: January 30, 2017 Abstract- The present study was conducted to analyse the impact of agricultural credit on agricultural development and constraints in advancing the agricultural credit. The study was conducted in the district of Bikaner region viz., Sriganganagar, Hanumangarh, Bikaner and Churu district. A lead bank of each selected district was selected purposively for collection of secondary and primary data in respect of agricultural loan supplied to the farmers. A sample of 30 farmers was drawn as borrower farmers from each selected district by probability proportion to the number of borrower farmers. The increasing trend was observed in the value of net worth with increase in farm size on both borrower and non-borrower farmers of the study area. At overall level about 47 to 50 per cent net worth value was higher on borrower farmers than the non-borrower farmers. The value of current assets was ranged from 1.81 to 3.82 on borrower farmers in comparison to non-borrower farmers 1.02 to 2.90. -

District Census Handbook, Churu, Rajasthan and Ajmer

CENSUS, 195 1 RAJASTHAN AND AJMER DISTRICT CERUS' ,HANDBOOK CHURU PART .-GENERAL DESCRIPTION AND CENSUS TABLES By Pt. YAMUNA LAL DASHORA, B.A., LL.B., Superintendent of Censl1s Operations, Rajasthan and Aimer. JODHPUR: P.RINTED AT THE GOVE]1};llENT PRESS 1956 1f.R:EFAcE, .... ,:, . - , 'The "CensuA Reports' ill' .qlq.en -·times :were printed one for the whole Province. of Ra.j putana and.another for A-jIl1:er-:Merwara._"Soin~ of the Principal 8tates now merged in Rajasthan published 'their own reports. This time the -State Census H eports have been published in the following volumes:- 1. Part I A .. Report. 2. Part 1--B .. ~ubsidiary Tables and District Index of Non-Agricultural Occupations. 3. Part I -C .. Appendices. 4. Part U-A .. r::eneral Population Tables, Household and Age Sample Tables, Social and Cultural Tables, Table E Summary Figures by Administrative Units, and Local 'KA' Infirmities. 5. Part II-B .. Economic Tables. They contain statistics down to the district level The idea of preparing the District Census Handbook separately for each district was put forward .by' Shri R. A. GopaJaswami. I. C. R., Registrar General. India, and ex-officio Census' Commissioner of' India, as part of a plan intended to secu~e an effective, method of preserving the census records prepared for areas below the qistrict level. 'He proposed that all the district, census tables and census abstracts prepared during the process of sorting and cOinpilatiori should be bound together in a single manuscript volume, called the District Census Handbook, and suggested to the State Governments that the Handbook (with or without the addition of other useful information relating to the district) should be printed and pub lished at their own cost in the same manner as the village statistics in the past. -

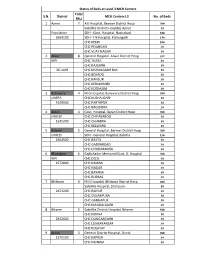

Status of Beds at Level 3 MCH Centers Total S.N

Status of Beds at Level 3 MCH Centers Total S.N. District MCH Centers L3 No. of Beds FRU 1 Ajmer 7 A K Hospital, Beawer District Hosp 300 Satellite District Hospital, Ajmer 30 Population SDH - Govt. Hospital, Nasirabad 100 2664100 SDH- Y N Hospital, Kishangarh 150 CHC KEKRI 100 CHC PISANGAN 30 CHC VIJAY NAGAR 30 2 Alwar 8 General Hospital, Alwar District Hosp 332 NIPI CHC TIJARA 30 CHC RAJGARH 50 36 LAKH CHC KISHANGARH BAS 50 CHC BEHROD 50 CHC BANSUR 30 CHC KERLIMANDI 30 CHC KOTKASIM 30 3 Banswara 4 M G Hospital, Banswara District Hosp 300 UNFPA CHC KUSHALGARH 50 1629900 CHC PARTAPUR 30 CHC BAGIDORA 30 4 Baran 4 Govt. Hospital, Baran District Hosp 300 UNICEF CHC CHIPABAROD 30 1245200 CHC CHHABRA 50 CHC KELWARA 30 5 Barmer 5 General Hospital, Barmer District Hosp 200 UNICEF SDH - General Hospital, Balotra 150 2404500 CHC BAYTU 30 CHC GADRAROAD 30 CHC DHORIMANNA 30 6 Bharatpur 6 RajBahadur Memorial Govt. D. Hospital 300 NIPI CHC DEEG 50 2572800 CHC KAMAN 30 CHC NAGAR 30 CHC BAYANA 50 CHC RUPBAS 30 7 Bhilwara 6 M G Hospital, Bhilwara District Hosp 400 Satellite Hospital, Shahpura 50 2453200 CHC RAIPUR 30 CHC GULABPURA 50 CHC GANGAPUR 50 CHC MANDALGARH 50 8 Bikaner 5 Satellite District Hospital, Bikaner 100 CHC NOKHA 50 2322600 CHC DUNGARGARH 30 CHC LUNKARANSAR 30 CHC KOLAYAT 30 9 Bundi 3 General District Hospital, Bundi 300 1170100 CHC KAPREN 30 CHC NAINWA 50 Total S.N. District MCH Centers L3 No. of Beds FRU 10 Chittorgarh 5 District Hospital, Chittorgarh 300 1629900 CHC BEGUN 50 CHC KAPASAN 50 CHC BADISADRI 50 CHC NIMBAHERA 100 11 Churu 5 D B Hospital, Churu District Hospital 225 2059300 SDH - S R J Hospital, Ratangarh 100 SDH - S B Hospital, Sujangarh 100 CHC RAJGARH 50 CHC SARDARSHAHAR 75 12 Dausa 3 District Hospital, Dausa 150 NIPI CHC LALSOT 30 1606100 CHC MAHUWA 30 13 Dholpur 4 Sadar District Hospital, Dholpur 300 1196300 CHC RAJAKHERA 30 CHC BARI 50 CHC BASERI 30 14 Dungarpur 4 General District Hospital, Dungarpur 300 UNICEF SDH - Govt. -

Government of Rajasthan Department of Women & Child Development

GOVERNMENT OF RAJASTHAN DEPARTMENT OF WOMEN & CHILD DEVELOPMENT DIRECTORATE OF WOMEN EMPOWERMENT Implementation of Protection of Women against Domestic Voilecne Act, 2005 1- Name of the State - RAJASTHAN 2- No. of Districts - 33 3- No. of Protection Officers appointed - 548 4- Details of Protection Officer- List enclosed LIST OF PROTECTION OFFICERS & SERVICE PROVIDERS UNDER THE PROTECTION OF WOMEN FROM DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACT, 2005 A) Protection Officers STATE-RAJASTHAN DISTRICT-AJMER Sr.No Name & address with contact numbers Designation 1 Shri S.D. Gaur, DD, ICDS, Women & Child Development, Ajmer (T) 0145-2627154 DD 2 Smt Kumudani Sharma, CDPO Office, Ajmer City, (R) 0145-2426452 (O) 0145-2620582 CDPO 3 Smt. Mithlesh Jain, CDPO Office, Kishangarh Rural, Ajmer (M) 9928266768 CDPO 4 Smt. Mithlesh Jain, CDPO Office, Arai, Ajmer (M) 9928266768 CDPO (Addl. Charge) 5 Shri Deepak Sharma, CDPO Office, Byvar City, Ajmer (M) 9928070768 CDPO 6 Shri Vinay Chandra Jain, CDPO Office, Kekari, Ajmer (M) 9351454499 CDPO 7 Smt. Asha Sharma, CDPO Office, Pisagan, Ajmer (M) 9414708211 CDPO 8 Smt. Geeta Sharma, CDPO Office, Jawaja, Ajmer (M) 9982591310 CDPO 9 Shri Vijay Chandra Chandra Jain, CDPO Office, Kishangarh City, Ajmer (M) 9351454499 CDPO 10 Smt. Saroj Chaturvedi, CDPO Office, Srinagar, Ajmer (M) 9460932605 CDPO 11 Smt. Ashu Choudhary, CDPO Office, Masuda, Ajmer Addl. Charge 12 Shri Vijay Chandra Jain, CDPO Office, Bhinai, Ajmer (M) 9351454499 CDPO 13 Smt. Krishna Sharma, CDPO Office, Masuda, Ajmer (M) 9460203200 Pracheta 14 Smt. Uschav Sharma, CDPO, Office, Arai, Ajmer (M) 9460150630 Pracheta 15 Miss Aruna Gupta, CDPO Office, Srinagar, Ajmer, (M) 9414281364 Pracheta 16 Smt.