Disseminating the Freak Show

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integration Des Chaos : Marilyn Manson, Männlichkeit, Lust Und Scheitern L'amour Lalove, Patsy 2017

Repositorium für die Geschlechterforschung Integration des Chaos : Marilyn Manson, Männlichkeit, Lust und Scheitern l'Amour laLove, Patsy 2017 https://doi.org/10.25595/398 Eingereichte Version / submitted version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: l'Amour laLove, Patsy: Integration des Chaos : Marilyn Manson, Männlichkeit, Lust und Scheitern, in: Nagelschmidt, Ilse; Borrego, Britta; Majewski, Daria; König, Lisa (Hrsg.): Geschlechtersemantiken und Passing be- und hinterfragen (Frankfurt am Main: PL Academic Research, 2017), 169-194. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25595/398. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY 4.0 Lizenz (Namensnennung) This document is made available under a CC BY 4.0 License zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden (Attribution). For more information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de www.genderopen.de Integration des Chaos – Marilyn Manson, Männlichkeit, Lust und Scheitern Patsy l'Amour laLove Marilyn Manson as a public figure represents exemplarily aspects of goth subculture: Aspects of life that shall be denied as not belonging to a fulfilled and happy life from a normative point of view are being integrated in a way that is marked by pleasure. Patsy l‘Amour laLove uses psychoanalytic approaches to the integration of chaos, of pain and failure in Manson‘s recent works. „This will hurt you worse than me: I'm weak, seven days a week ...“ Marilyn Manson1 FOTO © by Max Kohr: Marilyn Manson & Rammstein bei der Echo-Verleihung 2012 Für Fabienne. Marilyn Manson verwirft in seinem Werk die Normalität, um sich im gleichen Moment schmerzlich danach zu sehnen und schließlich den Wunsch nach Anpassung wieder wütend und lustvoll zu verwerfen. -

MM + NK = WM, Czyli Dlaczego Marilyn Manson Zakochałby Się W Nadkobiecie

Alicja Bemben Akademia Techniczno ‑Humanistyczna Katedra Anglistyki MM + NK = WM, czyli dlaczego Marilyn Manson zakochałby się w nadkobiecie Ale kiedyś, w czasach lepszych niż obecny rozkład, poja‑ wi się on, zbawiciel, człowiek wielkiej miłości i pogardy, stwórca, którego nieodparta siła nie pozwoli mu pozostać bezczynnym, którego samotność ludzie mylnie postrze‑ gają jako ucieczkę od rzeczywistości – podczas gdy jest to tylko jego sposób poznawania i przyjmowania rzeczy‑ wistości, tak więc, kiedy pewnego dnia znów się pojawi, przyniesie im wybawienie, ocali świat od przekleństwa idei panującej dotychczas. Człowiek przyszłości, który wybawi nas nie tylko od dotychczasowej idei, ale tak‑ że tego co musi z niej wyniknąć, wielkiego niesmaku, nihilizmu, samounicestwienia; on będzie niczym bicie dzwonów w południe, uwolni nasze umysły, przywróci światu cel, a człowiekowi nadzieję; ten Antychryst i an‑ tynihilista; zwycięzca Boga i nicości – pewnego dnia musi nadejść1. U schyłku XIX wieku przytoczone słowa stanowiły podsumowanie zapa‑ trywań Fryderyka Nietzschego na intelektualno ‑ideologiczny klimat panu‑ jący w ówczesnej Europie. U progu XXI wieku słowa te posłużyły Marily‑ nowi Mansonowi jako cytat otwierający jego (auto)biografię2. Jak dość łatwo 1 F. Nietzsche: Z genealogii moralności – cyt. za: M. Manson, N. Strauss: Trudna droga z piekła. [Tłum. M. Mejs]. Poznań: Kagra, 2000, s. [7]. 2 Do tej pory twórczość Mansona trzykrotnie została przedmiotem filozoficznych lub okołofilozoficznych rozważań. Zob. R. Wright: „I’d Sell You Suicide”. Pop Music and Moral Panic in the Age of Marilyn Manson. „Popular Music” 2000, vol. 19, no. 3, s. 365–385; P. Sme‑ yers, B. Lambeir: Carpe Diem. Tales of Desire and the Unexpected. „Journal of Philosophy of Education” 2002, no. -

Subjectivity in American Popular Metal: Contemporary Gothic, the Body, the Grotesque, and the Child

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Glasgow Theses Service Subjectivity In American Popular Metal: Contemporary Gothic, The Body, The Grotesque, and The Child. Sara Ann Thomas MA (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow January 2009 © Sara Thomas 2009 Abstract This thesis examines the subject in Popular American Metal music and culture during the period 1994-2004, concentrating on key artists of the period: Korn, Slipknot, Marilyn Manson, Nine Inch Nails, Tura Satana and My Ruin. Starting from the premise that the subject is consistently portrayed as being at a time of crisis, the thesis draws on textual analysis as an under appreciated approach to popular music, supplemented by theories of stardom in order to examine subjectivity. The study is situated in the context of the growing area of the contemporary gothic, and produces a model of subjectivity specific to this period: the contemporary gothic subject. This model is then used throughout to explore recurrent themes and richly symbolic elements of the music and culture: the body, pain and violence, the grotesque and the monstrous, and the figure of the child, representing a usage of the contemporary gothic that has not previously been attempted. Attention is also paid throughout to the specific late capitalist American cultural context in which the work of these artists is situated, and gives attention to the contradictions inherent in a musical form which is couched in commodity culture but which is highly invested in notions of the ‘Alternative’. In the first chapter I propose the model of the contemporary gothic subject for application to the work of Popular Metal artists of the period, drawing on established theories of the contemporary gothic and Michel Foucault’s theory of confession. -

Wpid-Merlin Menson Torrent Files Mp3.Pdf

Продолжительность. битрейт аудио. 128 кб/с. Marilyn Manson - Tourniquet. Продолжение... Похожие запросы: Продолжительность. битрейт аудио. 128 кб/с. Marilyn Manson - Tourniquet. Продолжительность. битрейт аудио. 128 кб/с. Marilyn Manson - About. XviD Продолжительность. битрейт аудио. 128 кб/с. Marilyn Manson - Coma White. Скриншоты. DVDRip. Marilyn Manson - Mobscene. MP3. Marilyn Manson - Disposable Teens. Продолжительность. битрейт аудио. 128 В 1996 году Marilyn Manson выпустил кавер-версию песни. depositfiles.com/fi Видео. 00:03:28. аудиокодек. Marilyn Manson - Personal Jesus. Аудио. Ск Search geazy marilyn download free mp3 or marilyn manson tainted love ск Cкачать торрент Marilyn Manson - Arma Goddamn Motherfuckin Geddon 2009 г., Marilyn Manson - Cryptorchid. Продолжительность. битрейт аудио. 128 кб/с. Marilyn Manson - This Is The New Shit. аудиокодек. Аудио. DVDRip. MP3. IMG http://torrents.net.ua/forum/art/3/98/122.jpg/IMG. BB изображение. Нажмите для увеличения, ссылка откроется в новом окне. Marilyn Manson - Ro Marilyn Manson - B-Sides & Rarities (2013) MP3 Название: Marilyn Manson - Marilyn play listen manson vire manson aug sweet High Speed Sweet Dreams Ma Tagged Keywords: marilyn manson torrent discography Related Keywords:Korn. Letra no heart cds mp Bloggers debate if manson get the nov sees Lyrics,mar Marilyn Manson вики,rumarilynmanson,Файл:Adsafwef.jpg,Marilyn Manson вики,r Marilyn Manson - This Is The New Shit. Возможно, вам понравятся также. Altwall: Информация, концерты и биография Marilyn Manson. 14.05.2015, 00:57. скачать торрент 15 таблетку fifa 15 скачать fifa торрент таблетку. sokd. Информация о музыке Исполнитель: Marilyn Manson Альбом: The Pale Emperor De IMG http://torrents.net.ua/forum/art/0/38/22.jpg/IMG. -

Elin Bryngelson/Rockfoto

10 juni, 2015, kl. 23:50 av Mattias Kling En väldigt svackande formkurva tycks ha vänt för gamle Mazza. Det känns lovande. Foto: Elin Bryngelson/Rockfoto Marilyn Manson Gröna Lund, Stockholm. Längd: Runt en timme och tjugo minuter. Publik: Cirka 17 000. Bäst: Från det att den vitspäckliga kavajen åker på. Sämst: Bh-kastningen på Twiggy Ramirez känns väldigt flåspubertal. Fråga: Kalsonger i stället? Jodå. Han rör ju på sig igen. Han verkar ju veta var han är – och uppträder med någon slags passion och närvaro. Kul? Jovars. Under mina över 20 år som på ett eller annat sätt avlönad rocktyckare har ingen annan artist haft ett större betygspann än just denna 46-årige chockrockare. För det har ju varit en väldigt skumpig färd. Från det sena 1990-talets provokativt galna väckelsemöten (väl värda sina fyra plus) till det pinsamma haveriet på Metaltown-festivalen 2009 – som ganska länge var det sämsta jag har sett av en etablerad artist på denna nivå. Fram till Mötley Crüe på Sweden Rock i helgen, det vill säga. Men nu verkar Marilyn Manson vara tillbaka på den nivå som årssläppet ”The pale emperor” ville antyda. Kanske inte lika tänd och omvälvande som tidigare, men ändå med en vilja och en hängivenhet som får de förlorade åren som har föregått detta att verka som en tillfällig svacka i karriären. En formdipp som har gått över. För lite så är det. Det är svårt att kalla huvudpersonen överdrivet energisk – vilket exempelvis märks när han med största möjliga ansträngning och möda går ner och torrknulla monitorerna i Eurythmics-covern ”Sweet dreams (Are made of this)” – men det är ändå en artist som faktiskt verkar vilja vara där. -

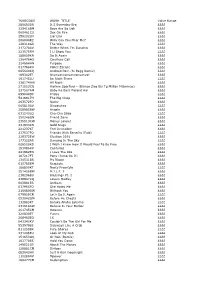

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl -

Leggi. Milano. Domani. Distribuzione Gra Tuita N

A PAGINA 5 Da Maciachini a NYC A PAGINA 12 Il coworking fai da te A PAGINA 15 Ogni dolce, un cocktail il crack di Brian Pallas scopriamo Make Milano l'idea dello chef Moschella Per le tue segnalazioni sulla nostra Milano 331.95.25.828 MITOMORROW.IT MITOMORROW.IT LUNEDÌ 18 GIUGNO 2018 LUNEDÌ ❱ ANNO 5 ❱ N. 109 DISTRIBUZIONE GRATUITA ❱ A due anni, domani, dal ballottaggio tra Sala e Parisi, DOMANI. il voto al primo cittadino da parte di un suo illustre predecessore. Albertini: «Per ora MILANO. è promosso, ma...» da pagina 10 LEGGI. cambiamilano Dal prossimo autunno Comune e Amsa avvieranno lo strumento del “Contatore Ambientale” per valutare i benefici della gestione dei rifiuti NAVIGLI RIAPERTI? OK DAGLI ARTIGIANI La differenziata che fa bene Il focus di vetro, alluminio, acciaio, carta, carto- saranno stati potenziati i servizi di rac- Piero Cressoni ne, legno e plastica vengono riciclati ri- colta differenziata nella zona ovest di ecuperare i Na- utilizzati e dunque quante e quali mate- Milano, estendendo a tutte le utenze vigli è un'ottima uanto vale la raccolta dif- rie prime vergini vengono risparmiate. I domestiche il servizio porta a porta del idea, soprattutto ferenziata a Milano? Dal dati, disponibili sul portale Open Data, cartone e riducendo la frequenza di riti- «Rse nel progetto prossimo autunno sul sito saranno facilmente consultabili sul sito ro del rifiuto indifferenziato. Il sistema, di fondo si riscoprono eccellenze Q del Comune sarà possibile istituzionale comune.milano.it. attivo nel 50% delle utenze milanesi, e tradizioni e si coglie l'occasione conoscere esattamente quali e quanti raggiungerà tutta la città entro il 2019. -

The Broadsheet

May 2018 Issue XXIV THE BROADSHEET Seniors pose with inductees to Sigma Tau Delta Fifth Annual English Awards Ceremony This Issue: Celebrates Shared Scholarship, Award-Winning Verse, and Seniors Preparing for Graduation Poetry, Sanity, and By The Broadsheet Staff the Fifth Annual English Award Approximately fifty faculty, staff, students and family attended the fifth Ceremony annual English Awards Ceremony held on April 12 at 4 pm at the Merrimack College Writers House. The event consisted of a robust agenda, which Guest Speaker Tanya included the induction of eight new members into the Sigma Tau Delta Larkin Guides International Honor Society, the distribution of graduation cords to nine Majors along an seniors, a slide show from four of the five English majors who presented Important Path original scholarly and creative works at this year’s Sigma Tau Delta annual Sigma Tau Delta convention, the awarding of cash prizes to the three place winners in the Rev. John R. Aherne 2018 Poetry Contest, and a reading by poet Tanya Larkin, Conference 2018 Tufts University Lecturer in Creative Writing and author of two collections of original poetry, My Scarlet Ways, winner of the 2011 Saturnalia prize, and The Cryptic Manson Hothouse Orphan. of Heaven Upside Down The program also included readings by Aherne Poetry contest winners Bridget Kennedy (“Where I’m From,” first place), Dan Roussel (“Things Creating a Life in the I’ve Never Done,” second place), and Dakota Durbin (“Deer” and “Lucy Automated Future: Brook,” which tied for third place in the contest voting). In addition to her Mark Cuban on the reading, Larkin shared her thoughts about why poetry remains crucial to Liberal Arts emotional wellbeing. -

“I Am Your Faggot Anti-Pope”: an Exploration of Marilyn Manson As a Transgressive Artist

European journal of American studies 12-2 | 2017 Summer 2017, including Special Issue: Popularizing Politics: The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election “I Am Your Faggot Anti-Pope”: An Exploration of Marilyn Manson as a Transgressive Artist Coco d’Hont Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12098 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.12098 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Coco d’Hont, « “I Am Your Faggot Anti-Pope”: An Exploration of Marilyn Manson as a Transgressive Artist », European journal of American studies [Online], 12-2 | 2017, document 14, Online since 01 August 2017, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12098 ; DOI : 10.4000/ ejas.12098 This text was automatically generated on 19 April 2019. Creative Commons License “I Am Your Faggot Anti-Pope”: An Exploration of Marilyn Manson as a Transgres... 1 “I Am Your Faggot Anti-Pope”: An Exploration of Marilyn Manson as a Transgressive Artist Coco d’Hont 1 “As a performer,” Marilyn Manson announced in his autobiography, “I wanted to be the loudest, most persistent alarm clock I could be, because there didn’t seem to be any other way to snap society out of its Christianity- and media-induced coma” (Long Hard Road 80).i With this mission statement, expressed in 1998, the performer summarized a career characterized by harsh-sounding music, disturbing visuals, and increasingly controversial live performances. At first sight, the red thread running through the albums he released during the 1990s is a harsh attack on American ideologies. On his debut album Portrait of an American Family (1994), for example, Manson criticizes ideological constructs such as the nuclear family, arguing that the concept is often used to justify violent pro-life activism.ii Proclaiming that “I got my lunchbox and I’m armed real well” and that “next motherfucker’s gonna get my metal,” he presents himself as a personification of teenage angst determined to destroy his bullies, be they unfriendly classmates or the American government. -

Plan Dieta Y Ejercicio Te Paso Unos Links Que Te Van a Ser De Utilidad

Plan Dieta Y Ejercicio te paso unos links que te van a ser de utilidad. Tienen dietas, planes de peso, http://www.dietaclub.com/ http://www.dietascormillot.com/ http://www.drcormillot.com Espero te sean de utilidad. Pero ante todo recorda que no existen las dietas magicas, el tema es cambiar tus habitos alimentarios y hacer ejercicio fisico. Ese es el secreto. tenes que aprender a comer de nuevo, para olvidarte definitivamente de tus problemas de sobrepeso de por vida. Desconfia de todo aquello que te prometa resultados rapidos y con poco esfuerzo.....irremediablemente volveras a recuperar peso en cuanto dejes de tomar tal o cual pastilla o comiences a comer alguna cosa de mas. Entra a chusmear los links que te pase...y suerte!!! Sigue leyendo → ¿ Es posible eliminar solo con ejercicios y dieta el abdomen. Un abdomen con una circunferencia de 120cm, femenina, un parto, sufre de estreñimiento, y toma poco liquido es posible aplanarlo, como? Sigue leyendo → necesito adelgazar alguien sabe un buen producto que pueda usar, como pastillas o tes, las dietas no me dan resultados.. Sigue leyendo → Hola. Tengo 15 años y quisiera saber qué dieta y rutina de ejercicios puedo hacer para bajar de peso y marcar mi abdomen. Sobre los ejercicios hay gran variedad pues es Salir a trotar de 30 a 60 minutos, también puedes andar en bicicleta, saltar la cuerda, el Cardio, los aerobics étc. Para marcar el abdomen pues es de ley los abdominales, pero también otros ejercicios Te dejo un link de los ejercicios que puedes hacer: http://www.ehowenespanol.com/mejor-ejercicio- abdominales-excelentes-10-dias-sobre_126182/ Y sobre lo de la dieta, es mejor que vayas a un nutriólogo porque ahí pueden darte un plan alimenticio de acuerdo a tu cuerpo y función de tu metabolismo. -

Transgressive Queer Embodiment in the Music Videos of Marilyn Manson

“It’s All Me… In One Way or Another”: Transgressive Queer Embodiment in the Music Videos of Marilyn Manson by Brandon Peter Masterman Bachelor of Music in Saxophone Performance, Youngstown State University, 2007 Master of Library and Information Science, University of Pittsburgh, 2008 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This thesis was presented by Brandon Peter Masterman It was defended on March 30, 2012 and approved by James P. Cassaro, MA, MLS, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Music Deane L. Root, PhD, Professor of Music Todd W. Reeser, PhD, Associate Professor of French Thesis Advisor: Adriana Helbig, PhD, Assistant Professor of Music ii Copyright © by Brandon Peter Masterman 2012 iii “It’s All Me… In One Way or Another”: Transgressive Queer Embodiment in the Music Videos of Marilyn Manson Brandon Peter Masterman, M.L.I.S., M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 My work attempts to understand the deployment of transgressive queerness in contemporary American popular music videos. Rather than aligning with either the conservative moral panics or liberal arguments regarding free speech, I suggest that productive alternative understandings exist outside of this oppositional binary. Focusing on Marilyn Manson, particularly, I analyze how various performances open up a space of potentiality for greater imaginings of embodiment and erotics. The music of Marilyn Manson presents a scathing critique of the cultural landscape of the United States in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. -

Lvlz Media Company Presenta

LVLZ MEDIA COMPANY PRESENTA: ANNO I NUMERO 6 18-24 FEBBRAIO 2017 Direttore Responsabile: Laura Primiceri Direttore Editoriale: Francesco Stati Caporedattore: Francesco Spagnol Responsabile Tecnico: Jacopo Nisticò, Valerio Bastianelli Hanno inoltre collaborato a questo numero: Claudio Agave, Michele Corato, Vittorio Comand, Arnaldo Figoni, Adriano Koleci, Raffaele Lauretti, Carlo Paganessi, Filippo Tiberi, Stefano Urso Revisione a cura di Francesco Spagnol La copertina e l’intestazione grafica sono diJacopo Castelletti. theWise è una testata giornalistica che, attraverso un’indagine condotta sui fatti in senso stretto, si propone di trattare Anno I, Numero 6 - 18-24 Febbraio 2017 argomenti di interesse generale con precisione e professionalità, fornendo una chiave interpretativa semplice, chiara e In questo qualificata. numero: Francesco Stati Eccellenza in pillole: Cosetta Pittau e la Tipografia 4 Grifani Donati Adriano Koleci La cyberguerra è iniziata: temete, nemici delle 7 mail Carlo Paganessi 10 Ubuntu: la leadership politica in Africa Stefano Urso Essere esclusi in classe: quando il bullismo non è 14 solo lividi Michele Corato L’eutanasia in Europa: diritto alla libertà, fino alla 18 fine Vittorio Comand 21 Sanremo 2017: un altro passo verso il baratro Arnaldo Figoni Da Marilyn Manson ai Grammy: fronte comune 23 anti-Trump Raffaele Lauretti 26 Storia del pensiero filosofico: Aristotele Filippo Tiberi 29 Minecraft e i suoi eredi Claudio Agave theWise incontra: Dellimellow, il grandissimo 32 vlogger 3 La grandezza del nostro Paese non si misura solamente con i successi delle grandi imprese, ma anche e soprattutto con il lavoro delle piccole eccellenze di cui è costellata la Penisola. Questa settimana inauguriamo la rubrica “Eccellenza in pillole”, che si prefigge lo scopo di fare da megafono a quelle realtà professionali poco reclamizzate dai media ma enormemente importanti per l’economia, la fama e l’eccellenza dell’Italia.