Psychedelics and Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ayahuasca: Spiritual Pharmacology & Drug Interactions

Ayahuasca: Spiritual Pharmacology & Drug Interactions BENJAMIN MALCOLM, PHARMD, MPH [email protected] MARCH 28 TH 2017 AWARE PROJECT Can Science be Spiritual? “Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality. When we recognize our place in an immensity of light years and in the passage of ages, when we grasp the intricacy, beauty and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual. The notion that science and spirituality are somehow mutually exclusive does a disservice to both.” – Carl Sagan Disclosures & Disclaimers No conflicts of interest to disclose – I don’t get paid by pharma and have no potential to profit directly from ayahuasca This presentation is for information purposes only, none of the information presented should be used in replacement of medical advice or be considered medical advice This presentation is not an endorsement of illicit activity Presentation Outline & Objectives Describe what is known regarding ayahuasca’s pharmacology Outline adverse food and drug combinations with ayahuasca as well as strategies for risk management Provide an overview of spiritual pharmacology and current clinical data supporting potential of ayahuasca for treatment of mental illness Pharmacology Terms Drug ◦ Term used synonymously with substance or medicine in this presentation and in pharmacology ◦ No offense intended if I call your medicine or madre a drug! Bioavailability ◦ The amount of a drug that enters the body and is able to have an active effect ◦ Route specific: bioavailability is different between oral, intranasal, inhalation (smoked), and injected routes of administration (IV, IM, SC) Half-life (T ½) ◦ The amount of time it takes the body to metabolize/eliminate 50% of a drug ◦ E.g. -

House Bill No. 1176

FIRST REGULAR SESSION HOUSE BILL NO. 1176 101ST GENERAL ASSEMBLY INTRODUCED BY REPRESENTATIVE DAVIS. 2248H.01I DANA RADEMAN MILLER, Chief Clerk AN ACT To repeal sections 191.480 and 579.015, RSMo, and to enact in lieu thereof two new sections relating to investigational drugs. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the state of Missouri, as follows: Section A. Sections 191.480 and 579.015, RSMo, are repealed and two new sections 2 enacted in lieu thereof, to be known as sections 191.480 and 579.015, to read as follows: 191.480. 1. For purposes of this section, the following terms shall mean: 2 (1) "Eligible patient", a person who meets all of the following: 3 (a) Has a debilitating, life-threatening, or terminal illness; 4 (b) Has considered all other treatment options currently approved by the United States 5 Food and Drug Administration and all relevant clinical trials conducted in this state; 6 (c) Has received a prescription or recommendation from the person's physician for an 7 investigational drug, biological product, or device; 8 (d) Has given written informed consent which shall be at least as comprehensive as the 9 consent used in clinical trials for the use of the investigational drug, biological product, or device 10 or, if the patient is a minor or lacks the mental capacity to provide informed consent, a parent or 11 legal guardian has given written informed consent on the patient's behalf; and 12 (e) Has documentation from the person's physician that the person has met the 13 requirements of this subdivision; 14 (2) "Investigational drug, biological product, or device", a drug, biological product, or 15 device, any of which are used to treat the patient's debilitating, life-threatening, or terminal 16 illness, that has successfully completed phase one of a clinical trial but has not been approved EXPLANATION — Matter enclosed in bold-faced brackets [thus] in the above bill is not enacted and is intended to be omitted from the law. -

Preparation for a Workshop How to Prepare for Healing

Preparation for a Workshop How to Prepare for Healing with Ayahuasca The Temple of the Way of Light http://templeofthewayoflight.org/ How to Prepare for Healing with Ayahuasca 2 Why Preparation is Important Comprehensive preparation for working with ayahuasca and a resolute commitment to ongoing integration after your retreat are as important as the healing you will experience whilst at the Temple. It is critical that you commit at the deepest level possible to the advice contained in this document – before, during and after your retreat – in order to ensure your healing experience is positive, safe and sustained over the long term. M any people from the West who are new to ayahuasca come with a misconception of the way the medicine works. There is no “quick fix” when awakening to higher aspects of consciousness or alleviating long-term pain and suffering. We can never offer any guarantees regarding healing, but we do sincerely and wholeheartedly promise to always try our best. Indigenous traditions have worked with ayahuasca for thousands of years and have never viewed it as a quick fix or a recreational experience. However, ayahuasca and the healing traditions of the Amazon are often able to offer a significant intervention into chronic emotional/psycho-spiritual imbalances and, sometimes, physical health conditions. It is fundamentally a transformational pathway to integrate and release the causes of pain and suffering. Ayahuasca is a powerful cleansing and purifying medicine that can rid the body of physical impurities, the mind and body of emotional blockages and self-limiting fear-filled patterns that have accumulated over a lifetime, as well as retrieve fragmented aspects of one’s soul due to past traumatic events. -

Hallucinogens and Dissociative Drugs

Long-Term Effects of Hallucinogens See page 5. from the director: Research Report Series Hallucinogens and dissociative drugs — which have street names like acid, angel dust, and vitamin K — distort the way a user perceives time, motion, colors, sounds, and self. These drugs can disrupt a person’s ability to think and communicate rationally, or even to recognize reality, sometimes resulting in bizarre or dangerous behavior. Hallucinogens such as LSD, psilocybin, peyote, DMT, and ayahuasca cause HALLUCINOGENS AND emotions to swing wildly and real-world sensations to appear unreal, sometimes frightening. Dissociative drugs like PCP, DISSOCIATIVE DRUGS ketamine, dextromethorphan, and Salvia divinorum may make a user feel out of Including LSD, Psilocybin, Peyote, DMT, Ayahuasca, control and disconnected from their body PCP, Ketamine, Dextromethorphan, and Salvia and environment. In addition to their short-term effects What Are on perception and mood, hallucinogenic Hallucinogens and drugs are associated with psychotic- like episodes that can occur long after Dissociative Drugs? a person has taken the drug, and dissociative drugs can cause respiratory allucinogens are a class of drugs that cause hallucinations—profound distortions depression, heart rate abnormalities, and in a person’s perceptions of reality. Hallucinogens can be found in some plants and a withdrawal syndrome. The good news is mushrooms (or their extracts) or can be man-made, and they are commonly divided that use of hallucinogenic and dissociative Hinto two broad categories: classic hallucinogens (such as LSD) and dissociative drugs (such drugs among U.S. high school students, as PCP). When under the influence of either type of drug, people often report rapid, intense in general, has remained relatively low in emotional swings and seeing images, hearing sounds, and feeling sensations that seem real recent years. -

Soma and Haoma: Ayahuasca Analogues from the Late Bronze Age

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3(2), pp. 104–116 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.013 First published online July 25, 2019 Soma and Haoma: Ayahuasca analogues from the Late Bronze Age MATTHEW CLARK* School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), Department of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics, University of London, London, UK (Received: October 19, 2018; accepted: March 14, 2019) In this article, the origins of the cult of the ritual drink known as soma/haoma are explored. Various shortcomings of the main botanical candidates that have so far been proposed for this so-called “nectar of immortality” are assessed. Attention is brought to a variety of plants identified as soma/haoma in ancient Asian literature. Some of these plants are included in complex formulas and are sources of dimethyl tryptamine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and other psychedelic substances. It is suggested that through trial and error the same kinds of formulas that are used to make ayahuasca in South America were developed in antiquity in Central Asia and that the knowledge of the psychoactive properties of certain plants spreads through migrants from Central Asia to Persia and India. This article summarizes the main arguments for the botanical identity of soma/haoma, which is presented in my book, The Tawny One: Soma, Haoma and Ayahuasca (Muswell Hill Press, London/New York). However, in this article, all the topics dealt with in that publication, such as the possible ingredients of the potion used in Greek mystery rites, an extensive discussion of cannabis, or criteria that we might use to demarcate non-ordinary states of consciousness, have not been elaborated. -

Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca: Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Monoamine Metabolite Excretion and Pharmacokinetics

TESI DOCTORAL HUMAN PHARMACOLOGY OF AYAHUASCA JORDI RIBA Barcelona, 2003 Director de la Tesi: DR. MANEL JOSEP BARBANOJ RODRÍGUEZ A la Núria, el Marc i l’Emma. No pasaremos en silencio una de las cosas que á nuestro modo de ver llamará la atención... toman un bejuco llamado Ayahuasca (bejuco de muerto ó almas) del cual hacen un lijero cocimiento...esta bebida es narcótica, como debe suponerse, i á pocos momentos empieza a producir los mas raros fenómenos...Yo, por mí, sé decir que cuando he tomado el Ayahuasca he sentido rodeos de cabeza, luego un viaje aéreo en el que recuerdo percibia las prespectivas mas deliciosas, grandes ciudades, elevadas torres, hermosos parques i otros objetos bellísimos; luego me figuraba abandonado en un bosque i acometido de algunas fieras, de las que me defendia; en seguida tenia sensación fuerte de sueño del cual recordaba con dolor i pesadez de cabeza, i algunas veces mal estar general. Manuel Villavicencio Geografía de la República del Ecuador (1858) Das, was den Indianer den “Aya-huasca-Trank” lieben macht, sind, abgesehen von den Traumgesichten, die auf sein persönliches Glück Bezug habenden Bilder, die sein inneres Auge während des narkotischen Zustandes schaut. Louis Lewin Phantastica (1927) Agraïments La present tesi doctoral constitueix la fase final d’una idea nascuda ara fa gairebé nou anys. El fet que aquest treball sobre la farmacologia humana de l’ayahuasca hagi estat una realitat es deu fonamentalment al suport constant del seu director, el Manel Barbanoj. Voldria expressar-li la meva gratitud pel seu recolzament entusiàstic d’aquest projecte, molt allunyat, per la natura del fàrmac objecte d’estudi, dels que fins al moment s’havien dut a terme a l’Àrea d’Investigació Farmacològica de l’Hospital de Sant Pau. -

(DMT), Harmine, Harmaline and Tetrahydroharmine: Clinical and Forensic Impact

pharmaceuticals Review Toxicokinetics and Toxicodynamics of Ayahuasca Alkaloids N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), Harmine, Harmaline and Tetrahydroharmine: Clinical and Forensic Impact Andreia Machado Brito-da-Costa 1 , Diana Dias-da-Silva 1,2,* , Nelson G. M. Gomes 1,3 , Ricardo Jorge Dinis-Oliveira 1,2,4,* and Áurea Madureira-Carvalho 1,3 1 Department of Sciences, IINFACTS-Institute of Research and Advanced Training in Health Sciences and Technologies, University Institute of Health Sciences (IUCS), CESPU, CRL, 4585-116 Gandra, Portugal; [email protected] (A.M.B.-d.-C.); ngomes@ff.up.pt (N.G.M.G.); [email protected] (Á.M.-C.) 2 UCIBIO-REQUIMTE, Laboratory of Toxicology, Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Porto, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal 3 LAQV-REQUIMTE, Laboratory of Pharmacognosy, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Porto, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal 4 Department of Public Health and Forensic Sciences, and Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, 4200-319 Porto, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.D.-d.-S.); [email protected] (R.J.D.-O.); Tel.: +351-224-157-216 (R.J.D.-O.) Received: 21 September 2020; Accepted: 20 October 2020; Published: 23 October 2020 Abstract: Ayahuasca is a hallucinogenic botanical beverage originally used by indigenous Amazonian tribes in religious ceremonies and therapeutic practices. While ethnobotanical surveys still indicate its spiritual and medicinal uses, consumption of ayahuasca has been progressively related with a recreational purpose, particularly in Western societies. The ayahuasca aqueous concoction is typically prepared from the leaves of the N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT)-containing Psychotria viridis, and the stem and bark of Banisteriopsis caapi, the plant source of harmala alkaloids. -

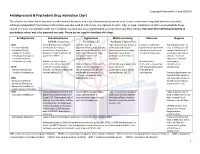

Antidepressant & Psychedelic Drug Interaction Chart

Copyright Psychedelic School 8/2020 Antidepressant & Psychedelic Drug Interaction Chart This chart is not intended to be used to make medical decisions and is for informational purposes only. It was constructed using data whenever possible, although extrapolation from known information was also used to inform risk. Any decision to start, stop, or taper medication and/or use psychedelic drugs should be made in conjunction with your healthcare provider(s). It is recommended to not perform any illicit activity. This chart the intellectual property of psychedelic school and is for personal use only. Please do not copy or distribute this chart. Antidepressant Phenethylamines Tryptamines MAOI-containing Ketamine Ibogaine -MDMA, mescaline -Psilocybin, LSD -Ayahuasca, Syrian Rue SSRIs Taper & discontinue at least 2 Consider taper & Taper & discontinue at least 2 Has been studied and Taper & discontinue at · Paroxetine (Paxil) weeks prior (all except discontinuation at least 2 weeks weeks prior (all except found effective both with least 2 weeks prior (all · Sertraline (Zoloft) fluoxetine) or 6 weeks prior prior (all except fluoxetine) or 6 fluoxetine) or 6 weeks prior and without concurrent except fluoxetine) or 6 · Citalopram (Celexa) (fluoxetine only) due to loss of weeks prior (fluoxetine only) (fluoxetine only) due to use of antidepressants weeks prior (fluoxetine · Escitalopram (Lexapro) psychedelic effect due to potential loss of potential risk of serotonin only) due to risk of · Fluxoetine (Prozac) psychedelic effect syndrome additive QTc interval · Fluvoxamine (Luvox) MDMA is unable to cause Recommended prolongation, release of serotonin when the Chronic antidepressant use may Life threatening toxicities can to be used in conjunction arrhythmias, or SPARI serotonin reuptake pump is result in down-regulation of occur with these with oral antidepressants cardiotoxicity · Vibryyd (Vilazodone) blocked. -

21 CFR Ch. II (4–1–10 Edition) § 1308.12

§ 1308.12 21 CFR Ch. II (4–1–10 Edition) Some trade and other names: N,N- whenever the existence of such salts, Diethyltryptamine; DET isomers, and salts of isomers is possible (18) Dimethyltryptamine ................................................. 7435 Some trade or other names: DMT within the specific chemical designa- (19) 5-methoxy-N,N-diisopropyltryptamine (other tion: name: 5-MeO-DIPT) ................................................... 7439 (1) gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (some other names in- (20) Ibogaine .................................................................. 7260 clude GHB; gamma-hydroxybutyrate; 4- Some trade and other names: 7-Ethyl- hydroxybutyrate; 4-hydroxybutanoic acid; sodium 6,6b,7,8,9,10,12,13-octahydro-2-methoxy-6,9- oxybate; sodium oxybutyrate) .................................... 2010 methano-5H-pyrido [1′, 2′:1,2] azepino [5,4-b] (2) Mecloqualone ........................................................... 2572 indole; Tabernanthe iboga (3) Methaqualone ........................................................... 2565 (21) Lysergic acid diethylamide ..................................... 7315 (22) Marihuana .............................................................. 7360 (f) Stimulants. Unless specifically ex- (23) Mescaline ............................................................... 7381 cepted or unless listed in another (24) Parahexyl—7374; some trade or other names: 3- schedule, any material, compound, Hexyl-1-hydroxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl- 6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran; Synhexyl. mixture, -

Hallucinogen-Like Actions of 5-Methoxy-N,N-Diisopropyltryptamine in Mice and Rats ⁎ W.E

Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior 83 (2006) 122–129 www.elsevier.com/locate/pharmbiochembeh Hallucinogen-like actions of 5-methoxy-N,N-diisopropyltryptamine in mice and rats ⁎ W.E. Fantegrossi a,b, , A.W. Harrington b, C.L. Kiessel b, J.R. Eckler c, R.A. Rabin c, J.C. Winter c, A. Coop d, K.C. Rice e, J.H. Woods b a Division of Neuroscience, Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Emory University, 954 Gatewood Road, Atlanta, GA 30322, United States b Department of Pharmacology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, United States c Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, United States d Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, Baltimore, MD, United States e Laboratory of Medicinal Chemistry, NIDDK, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD Received 2 June 2005; received in revised form 7 December 2005; accepted 29 December 2005 Available online 3 February 2006 Abstract Few studies have examined the effects of 5-methoxy-N,N-diisopropyltryptamine (5-MeO-DIPT) in vivo. In these studies, 5-MeO-DIPT was tested in a drug-elicited head twitch assay in mice where it was compared to the structurally similar hallucinogen N,N-dimethyltryptamine (N,N- DMT) and challenged with the selective serotonin (5-HT)2A antagonist M100907, and in a lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) discrimination assay in rats where its subjective effects were challenged with M100907 or the 5-HT1A selective antagonist WAY-100635. Finally, the affinity of 5- MeO-DIPT for three distinct 5-HT receptors was determined in rat brain. -

Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss

Supplemental Material can be found at: /content/suppl/2020/12/18/73.1.202.DC1.html 1521-0081/73/1/202–277$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/pharmrev.120.000056 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 73:202–277, January 2021 Copyright © 2020 by The Author(s) This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC Attribution 4.0 International license. ASSOCIATE EDITOR: MICHAEL NADER Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss Antonio Inserra, Danilo De Gregorio, and Gabriella Gobbi Neurobiological Psychiatry Unit, Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada Abstract ...................................................................................205 Significance Statement. ..................................................................205 I. Introduction . ..............................................................................205 A. Review Outline ........................................................................205 B. Psychiatric Disorders and the Need for Novel Pharmacotherapies .......................206 C. Psychedelic Compounds as Novel Therapeutics in Psychiatry: Overview and Comparison with Current Available Treatments . .....................................206 D. Classical or Serotonergic Psychedelics versus Nonclassical Psychedelics: Definition ......208 Downloaded from E. Dissociative Anesthetics................................................................209 F. Empathogens-Entactogens . ............................................................209 -

Chemical Composition of Traditional and Analog Ayahuasca

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujpd20 Chemical Composition of Traditional and Analog Ayahuasca Helle Kaasik , Rita C. Z. Souza , Flávia S. Zandonadi , Luís Fernando Tófoli & Alessandra Sussulini To cite this article: Helle Kaasik , Rita C. Z. Souza , Flávia S. Zandonadi , Luís Fernando Tófoli & Alessandra Sussulini (2020): Chemical Composition of Traditional and Analog Ayahuasca, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, DOI: 10.1080/02791072.2020.1815911 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2020.1815911 View supplementary material Published online: 08 Sep 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ujpd20 JOURNAL OF PSYCHOACTIVE DRUGS https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2020.1815911 Chemical Composition of Traditional and Analog Ayahuasca Helle Kaasik a, Rita C. Z. Souzab, Flávia S. Zandonadib, Luís Fernando Tófoli c, and Alessandra Sussulinib aSchool of Theology and Religious Studies; and Institute of Physics, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia; bLaboratory of Bioanalytics and Integrated Omics (LaBIOmics), Institute of Chemistry, University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Campinas, SP, Brazil; cInterdisciplinary Cooperation for Ayahuasca Research and Outreach (ICARO), School of Medical Sciences, University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Campinas, Brazil ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Traditional ayahuasca can be defined as a brew made from Amazonian vine Banisteriopsis caapi and Received 17 April 2020 Amazonian admixture plants. Ayahuasca is used by indigenous groups in Amazonia, as a sacrament Accepted 6 July 2020 in syncretic Brazilian religions, and in healing and spiritual ceremonies internationally.