African Union Union Africaine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Parliamentary Constituency Offices

REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA THE PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY OFFICES Parliament of Botswana P O Box 240 Gaborone Tel: 3616800 Fax: 3913103 Toll Free; 0800 600 927 e - mail: [email protected] www.parliament.gov.bw Introduction Mmathethe-Molapowabojang Mochudi East Mochudi West P O Box 101 Mmathethe P O Box 2397 Mochudi P O Box 201951 Ntshinoge Representative democracy can only function effectively if the Members of Tel: 5400251 Fax: 5400080 Tel: 5749411 Fax: 5749989 Tel: 5777084 Fax: 57777943 Parliament are accessible, responsive and accountable to their constituents. Mogoditshane Molepolole North Molepolole South The mandate of a Constituency Office is to act as an extension of Parliament P/Bag 008 Mogoditshane P O Box 449 Molepolole P O Box 3573 Molepolole at constituency level. They exist to play this very important role of bringing Tel: 3915826 Fax: 3165803 Tel: 5921099 Fax: 5920074 Tel: 3931785 Fax: 3931785 Parliament and Members of Parliament close to the communities they serve. Moshupa-Manyana Nata-Gweta Ngami A constituency office is a Parliamentary office located at the headquarters of P O Box 1105 Moshupa P/Bag 27 Sowa Town P/Bag 2 Sehithwa Tel: 5448140 Fax: 5448139 Tel: 6213756 Fax: 6213240 Tel: 6872105/123 each constituency for use by a Member of Parliament (MP) to carry out his or Fax: 6872106 her Parliamentary work in the constituency. It is a formal and politically neutral Nkange Okavango Palapye place where a Member of Parliament and constituents can meet and discuss P/Bag 3 Tutume P O Box 69 Shakawe P O Box 10582 Palapye developmental issues. Tel: 2987717 Fax: 2987293 Tel: 6875257/230 Tel: 4923475 Fax: 4924231 Fax: 6875258 The offices must be treated strictly as Parliamentary offices and must therefore Ramotswa Sefhare-Ramokgonami Selibe Phikwe East be used for Parliamentary business and not political party business. -

The Big Governance Issues in Botswana

MARCH 2021 THE BIG GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN BOTSWANA A CIVIL SOCIETY SUBMISSION TO THE AFRICAN PEER REVIEW MECHANISM Contents Executive Summary 3 Acknowledgments 7 Acronyms and Abbreviations 8 What is the APRM? 10 The BAPS Process 12 Ibrahim Index of African Governance Botswana: 2020 IIAG Scores, Ranks & Trends 120 CHAPTER 1 15 Introduction CHAPTER 2 16 Human Rights CHAPTER 3 27 Separation of Powers CHAPTER 4 35 Public Service and Decentralisation CHAPTER 5 43 Citizen Participation and Economic Inclusion CHAPTER 6 51 Transparency and Accountability CHAPTER 7 61 Vulnerable Groups CHAPTER 8 70 Education CHAPTER 9 80 Sustainable Development and Natural Resource Management, Access to Land and Infrastructure CHAPTER 10 91 Food Security CHAPTER 11 98 Crime and Security CHAPTER 12 108 Foreign Policy CHAPTER 13 113 Research and Development THE BIG GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN BOTSWANA: A CIVIL SOCIETY SUBMISSION TO THE APRM 3 Executive Summary Botswana’s civil society APRM Working Group has identified 12 governance issues to be included in this submission: 1 Human Rights The implementation of domestic and international legislation has meant that basic human rights are well protected in Botswana. However, these rights are not enjoyed equally by all. Areas of concern include violence against women and children; discrimination against indigenous peoples; child labour; over reliance on and abuses by the mining sector; respect for diversity and culture; effectiveness of social protection programmes; and access to quality healthcare services. It is recommended that government develop a comprehensive national action plan on human rights that applies to both state and business. 2 Separation of Powers Political and personal interests have made separation between Botswana’s three arms of government difficult. -

Download Publication

Impact Report 2020 The IPU The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) is the global organization of national parliaments. It was founded in 1889 as the first multilateral political organization in the world, encouraging cooperation and dialogue between all nations. Today, the IPU comprises 179 national member parliaments and 13 regional parliamentary bodies. It promotes democracy, helps parliaments become stronger, younger, gender-balanced and more diverse. It also defends the human rights of parliamentarians through a dedicated committee made up of MPs from around the world. Twice a year, the IPU convenes over 1,500 delegates and MPs in a world assembly, bringing a parliamentary dimension to the work of the United Nations and the implementation of the 2030 global goals. Cover: The Swiss Parliament adapted to the pandemic by introducing partitions between seats and obligatory facemasks for its members. © Fabrice COFFRINI/AFP Contents Foreword 4 OBJECTIVE 1 Build strong, democratic parliaments 6 OBJECTIVE 2 Advance gender equality and respect for women’s rights 10 OBJECTIVE 3 Protect and promote human rights 14 OBJECTIVE 4 Contribute to peacebuilding, conflict prevention and security 18 OBJECTIVE 5 Promote inter-parliamentary dialogue and cooperation 22 OBJECTIVE 6 Youth empowerment 26 OBJECTIVE 7 Mobilize parliaments around the global development agenda 30 OBJECTIVE 8 Bridge the democracy gap in international relations 34 Towards universal membership 38 Resource mobilization: How the IPU is funded? 39 IPU specialized meetings in 2020 40 Financial results 42 3 Adapting, assisting our Members and accelerating the IPU’s digital transformation 2020 was a game-changer for the IPU. Starting in March, the IPU had to completely reinvent itself to mitigate the effects of the pandemic on its activities. -

His Excellency

International Day of Democracy Parliamentary Conference on Democracy in Africa organized jointly by the Inter-Parliamentary Union and the Parliament of Botswana Gaborone, Botswana, 14 – 16 September 2009 SUMMARY RECORDS DIRECTOR OF CEREMONY (MRS MONICA MPHUSU): His Excellency the President of Botswana, Lieutenant General Seretse Khama Ian Khama, IPU President, Dr Theo-Ben Gurirab, Deputy Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Ms Thokozani Khupe, Former President of Togo Mr Yawovi Agboyibo, Members of the diplomatic community, President and founder of Community Development Foundation Ms Graça Machel, Honourable Speakers, Cabinet Ministers, Permanent Secretary to the President, Honourable Members of Parliament, Dikgosi, if at all they are here, Distinguished Guests. I wish to welcome you to the Inter-Parliamentary Union Conference. It is an honour and privilege to us as a nation to have been given the opportunity to host this conference especially during our election year. This conference comes at a time when local politicians are criss-crossing the country as the election date approaches. They are begging the general public to employ them. They want to be given five year contract. Your Excellencies, some of you would have observed from our local media how vibrant and robust our democracy is. This demonstrates the political maturity that our society has achieved over the past 43 years since we attained independence. Your Excellencies, it is now my singular honour and privilege to introduce our host, the Speaker of the National Assembly of the Republic -

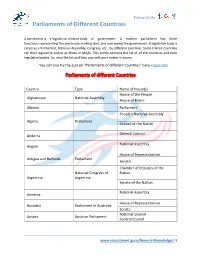

Parliaments of Different Countries

Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries A parliament is a legislative, elected body of government. A modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government. A legislative body is called as a Parliament, National Assembly, Congress, etc., by different countries. Some Islamic countries call their legislative bodies as Shora or Majlis. This article contains the list of all the countries and their legislative bodies. So, read the list and help yourself score better in exams. You can also try the quiz on “Parliaments of different Countries” here – Quiz Link Parliaments of different Countries Country Type Name of house(s) House of the People Afghanistan National Assembly House of Elders Albania Parliament People's National Assembly Algeria Parliament Council of the Nation General Council Andorra National Assembly Angola House of Representatives Antigua and Barbuda Parliament Senate Chamber of Deputies of the National Congress of Nation Argentina Argentina Senate of the Nation National Assembly Armenia House of Representatives Australia Parliament of Australia Senate National Council Austria Austrian Parliament Federal Council www.recruitment.guru/General-Knowledge/|1 Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries Azerbaijan National Assembly House of Assembly Bahamas, The Parliament Senate Council of Representatives Bahrain National Assembly Consultative Council National Parliament Bangladesh House of Assembly Barbados Parliament Senate House of Representatives National Assembly -

Of the Eleventh Parliament

DAILY YOUR VOICE IN PARLIAMENT THETHE SECOND FIRST MEETING MEETING OF THE O SECONDF THE FIFTH SESSION SESSION OF THE OF THE ELEVENTWELFTH PARLIAMENTTH PARLIAMENT THURSDAY 12 NOVEMBER 2020 MIXEDENGLISH VERSION VERSION HANSARDHANSARD NO. NO: 193 200 DISCLAIMER Unocial Hansard This transcript of Parliamentary proceedings is an unocial version of the Hansard and may contain inaccuracies. It is hereby published for general purposes only. The nal edited version of the Hansard will be published when available and can be obtained from the Assistant Clerk (Editorial). THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SPEAKER The Hon. Phandu T. C. Skelemani PH, MP. DEPUTY SPEAKER The Hon. Mabuse M. Pule, MP. (Mochudi East) Clerk of the National Assembly - Ms B. N. Dithapo Deputy Clerk of the National Assembly - Mr L. T. Gaolaolwe Learned Parliamentary Counsel - Ms M. Mokgosi Assistant Clerk (E) - Mr R. Josiah CABINET His Excellency Dr M. E. K. Masisi, MP. - President His Honour S. Tsogwane, MP. (Boteti West) - Vice President Minister for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Hon. K. N. S. Morwaeng, MP. (Molepolole South) - Administration Hon. K. T. Mmusi, MP. (Gabane-Mmankgodi) - Minister of Defence, Justice and Security Hon. Dr L. Kwape, MP. (Kanye South) - Minister of International Affairs and Cooperation Hon. E. M. Molale, MP. (Goodhope-Mabule ) - Minister of Local Government and Rural Development Hon. K. S. Gare, MP. (Moshupa-Manyana) - Minister of Agricultural Development and Food Security Minister of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation Hon. P. K. Kereng, MP. (Specially Elected) - and Tourism Hon. Dr E. G. Dikoloti MP. (Mmathethe-Molapowabojang) - Minister of Health and Wellness Hon. T.M. Segokgo, MP. -

ORGANIZATION of the LEGISLATURE September 12, 2008

CONSTITUTIONMAKING.ORG OPTION REPORTS ORGANIZATION OF THE LEGISLATURE September 12, 2008 The following report is one of a series produced by the Constitutional Design Group, a group of scholars dedicated to distributing data and analysis useful to those engaged in constitutional design. The primary intent of the reports is to provide current and historical information about design options in written constitutions as well as representative and illustrative text for important constitutional provisions. Most of the information in these reports comes from data from the Comparative Constitutions Project (CCP), a project sponsored by the National Science Foundation. Interested readers are encouraged to visit constitutionmaking.org for further resources for scholars and practitioners of constitutional design. Note that the dates provided herein for constitutional texts reflect either the year of initial promulgation or of a subsequent amendment, depending on the version used for analysis. For example, Brazil 2005 refers to the Brazilian Constitution of 1988, as amended through 2005. Copyright © 2008 ConstitutionMaking.org. All Rights Reserved. Option Report – Organization of Legislature 1 1. INTRODUCTION Legislatures are central institutions of modern government and found in both dictatorships and democracies. Important features of their organization are typically provided for in the national constitution. We describe below the range of constitutional provisions for the general organizational features of legislatures. 2. DATA SOURCE(S) The analysis reported below is based on data the Comparative Constitutions Project (please see the appendix for more information on this resource). As of this writing, the project sample includes 550 of the roughly 800 constitutions put in force since 1789, including more than 90% of constitutions written since World War II. -

The Road to Botswana Parliament

THE ROAD TO BOTSWANA PARLIAMENT BOTSWANA GENERAL ELECTIONS (1965-2009) Compiled by Research & Information Services Division Copyright © 2012 By Parliament of Botswana All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the author Table of Contents PREFACE 1 1. Introduction 2 2. 1965 General Elections 4 3. 1969 General Elections 5 4. 1974 General Elections 7 5. 1979 General Elections 8 6. 1984 General Elections 9 7. 1989 General Elections 11 8. 1994 General Elections 12 9. 1999 General Elections 14 10. 2004 General Elections 17 11. 2009 General Elections 19 12. Election Trends 1965 to 2009 22 13. Conclusion 22 REFERENCES 26 APPENDICES 27 APP.1: Composition of Botswana Parliament 1965 27 APP.2: Composition of Botswana Parliament 1969 29 APP.3: Composition of Botswana Parliament 1974 31 APP.4: Composition of Botswana Parliament 1979 33 APP.5: Composition of Botswana Parliament 1984 35 APP.6: Composition of Botswana Parliament 1989 37 APP.7: Composition of Botswana Parliament 1994 39 APP.8: Composition of Botswana Parliament 1999 41 APP.9: Composition of Botswana Parliament 2004 43 APP.10: Composition of Botswana Parliament 2009 46 APP.11: Supervisor of Elections 1965 to 2009 49 APP.12: Clerks of the National Assembly 1965 to 2009 49 APP.13: Abbreviations 49 LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Results of the 1965 general elections 5 Table 2: Results of the 1969 general elections 6 Table 3: Results of the 1974 general elections 8 Table 4: Results of the 1979 general -

Botswana Constitution

[Chap0000]CONSTITUTION OF BOTSWANA ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS CHAPTER I The Republic 1. Declaration of Republic 2. Public Seal CHAPTER II Protection of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms of the Individual 3. Fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual 4. Protection of right to life 5. Protection of right to personal liberty 6. Protection from slavery and forced labour 7. Protection from inhuman treatment 8. Protection from deprivation of property 9. Protection for privacy of home and other property 10. Provisions to secure protection of law 11. Protection of freedom of conscience 12. Protection of freedom of expression 13. Protection of freedom of assembly and association 14. Protection of freedom of movement 15. Protection from discrimination on the grounds of race, etc. 16. Derogation from fundamental rights and freedoms 17. Declarations relating to emergencies 18. Enforcement of protective provisions 19. Interpretation and savings CHAPTER III Citizenship 20 to 29 inclusive. [Repealed.] CHAPTER IV The Executive PART I The President and the Vice-President 30. Office of President 31. First President 32. Election of President after dissolution of Parliament 33. Qualification for election as President 34. Tenure of office of President 35. Vacancy in office of President 36. Discharge of functions of President during absence, illness, etc. 37. Oath of President 38. Returning officer at elections of President 39. Vice-President 40. Salary and allowances of President 41. Protection of President in respect of legal proceedings PART II The Cabinet 42. Ministers and Assistant Ministers 43. Tenure of office of Ministers and Assistant Ministers 44. Cabinet 45. Oaths to be taken by Ministers and Assistant Ministers 46. -

The Discourse of Dependency and the Agrarian Roots of Welfare Doctrines in Africa: the Case of Botswana1

© 2017 SOZIALPOLITIK.CH VOL. 2/2017 – ARTICLE 2.4 The discourse of dependency and the agrarian roots of welfare doctrines in Africa: The case of Botswana1 Jeremy SEEKINGS2 University of Cape Town Abstract Political elites across much of Africa have criticized welfare programmes and the idea of a welfare state for fostering dependency. Anxiety over dependency is not unique to East or Southern Africa, but the discourse of dependency in countries such as Botswana differs in important respects to the discourses of dependency articulated in some industrialised societies (notably the USA). This paper examines African dis- courses of dependency through a case-study of Botswana. The paper traces the gene- alogy of dependency through programmatic responses to drought between the 1960s and 1990s, and a reaction in the 2000s. The growth of a discourse of dependency re- flected both social and economic concerns: Socially, it was rooted in pre-existing un- derstandings of the reciprocal responsibilities associated with kinship and communi- ty; economically, the emergence of a discourse of dependency reflected the rise of an approach to development rooted in nostalgic conceptions of hard-working small farmers. The discourse of dependency appealed to both conservatives (offended by anti-social individualism) and economic modernisers (eager for an explanation for the failures of the developmental project to eliminate poverty). Keywords: Botswana, dependency, social assistance, welfare, discourse Introduction Welfare states in Africa are distinguished by their design as well as their apparently low overall level of expenditure. Most Anglophone countries in Africa emphasise forms of social assis- tance – with benefits in cash or kind, including in response to drought – rather than social insurance. -

48Th Plenary Discusses Terrorism, Food Security

Volume 02/2020 A newsletter of the SADC Parliamentary Forum focusing on the Plenary Assembly Session 48th Plenary discusses terrorism, food security ...as DRC lands Presidency The Plenary In This Edition From the SADC MPs want end to armed President insurgency in Mozambique ..............3 of SADC PF MPs call for debt waiver ...................5 Honourable Hon. Speaker Esperanca Laurinda Francisco Nhiuane Bias. DRC lands SADC PF Presidency, elcome to the second and final edition ofThe Plenary newsletter for the backs Regional Parliament bid .........6 year 2020. W As the curtain draws over the year 2020 – indeed, a year that many of us would rather forget on account of the many unprecedented challenges that the world experienced during it – I take this opportunity to commend all SADC Women and girls bearing brunt of PF Member States and SADC PF – affiliated National Parliaments as well as all COVID-19 - RWPC Chairperson.....7 Members of Parliament, for resilience and the ability to quickly adapt to trying circumstances. As the world responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, many of our governments introduced a raft of sometimes socioeconomically painful but necessary responses Outgoing SADC PF President to stem the spread of the virus. These included staying at home and working from upbeat about the Forum .....................7 home, teaching and learning using online platforms, mandatory use of masks and social distancing. Almost immediately, face-to-face interaction was suspended. That presented a challenge for SADC PF, which had hitherto been convening face-to-face meetings Hon Jeanine Mabunda Lioko pays that include joint sittings of standing committees of the Forum as well as Plenary homage to the women of SADC ......8 Assembly Sessions. -

FACTS-ABOUT-PARLIAMENT-BROCHURE.Pdf

What is a Member of Parliament? How does a bill become a law? Members of Parliament have been elected by Batswana A bill becomes a law after it has been passed in the Republic of Botswana voters to represent them in Parlimanent. There are same form by Parliament and is signed by the President. a total of 63 Members of Parliment. The President, the Speaker and 57 elected Members and 6 Specially It is then called an Act of Parliament. For a bill to be PARLIAMENT OF BOTSWANA elected Members (referred to as MPs). passed, it must be agreed to by a majority vote in the OUR PARLIAMENT OUR PRIDE House. A bill may also be sent to a parliamentary committee for further investigation before being voted on by Parliament. 57+6=63 If Members of Parliament agree on a bill, it may only take a couple of days to be passed through Parliament. What is a Minister? However, the process may take weeks or even months if A Minister is a Member of Parliament who is there is a lot of debate and disagreement, e.g deferred given a specific area of responsibility, also known for further consultation. An example of such a bill was as portfolio. Most Ministers are in charge of the Public Health Bill of 2013. goverment Ministries/Departments or assist in the administration of a Ministry or Department, such as as the Ministry of Education and Skills Development. How can the community affect Ministers work with their Ministries or Departments, decision-making in Parliament? as well as community organisations and professional Parliament’s role is to make decisions on behalf of associations to prepare new laws and change old all Batswana; it is interested in finding out what the laws which need updating.