The Discourse of Dependency and the Agrarian Roots of Welfare Doctrines in Africa: the Case of Botswana1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sir Ketumile Masire Factor in the Making of Botswana As an ‘African Miracle’

Botswana Notes and Records, Volume 50, 2018 The Sir Ketumile Masire Factor in the Making of Botswana as an ‘African Miracle’ Emmanuel Botlhale∗ Abstract Economic growth and development are associated with or caused by many variables one of which is leadership. The functional approach of leadership holds that leadership is not about an individual and his/her attributes. Rather, it is about a group and its attributes. However, it is unwieldy to focus on the role of the entire leadership in impacting macro-economic outcomes such as economic growth and development. Therefore, this paper discusses Sir Ketumile Masire’s role in shaping Botswana’s economic and development trajectory as founding Deputy Prime Minister, founding Vice President and Finance Minister and, latterly, President. It concludes that he provided leadership which very favourably circumstanced Botswana to become a relative economic and developmental success. In the process, the country earned accolades such as the ‘African Miracle’. However, serious macro-economic challenges such as persistent poverty and massive income inequality detract from these economic and developmental achievements. Hence, there is a need to determinedly address them to ensure prosperity for all or at least for the great majority of the country’s citizens. Introduction To establish relationships between variables (say X and Y), statistical concepts of correlation (associational relationship) and causation (cause and effect) are vital. Even though the two are related, they are also different. Furthermore, correlation does not imply causation. In this regard, a famous slogan in statistics cautions that ‘correlation does not imply causation’ (Mumford and Anjum 2013:1). Therefore, ‘even if there is a very strong association between two variables we cannot assume that one causes the other’ (McLeod 2008:1). -

The Parliamentary Constituency Offices

REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA THE PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY OFFICES Parliament of Botswana P O Box 240 Gaborone Tel: 3616800 Fax: 3913103 Toll Free; 0800 600 927 e - mail: [email protected] www.parliament.gov.bw Introduction Mmathethe-Molapowabojang Mochudi East Mochudi West P O Box 101 Mmathethe P O Box 2397 Mochudi P O Box 201951 Ntshinoge Representative democracy can only function effectively if the Members of Tel: 5400251 Fax: 5400080 Tel: 5749411 Fax: 5749989 Tel: 5777084 Fax: 57777943 Parliament are accessible, responsive and accountable to their constituents. Mogoditshane Molepolole North Molepolole South The mandate of a Constituency Office is to act as an extension of Parliament P/Bag 008 Mogoditshane P O Box 449 Molepolole P O Box 3573 Molepolole at constituency level. They exist to play this very important role of bringing Tel: 3915826 Fax: 3165803 Tel: 5921099 Fax: 5920074 Tel: 3931785 Fax: 3931785 Parliament and Members of Parliament close to the communities they serve. Moshupa-Manyana Nata-Gweta Ngami A constituency office is a Parliamentary office located at the headquarters of P O Box 1105 Moshupa P/Bag 27 Sowa Town P/Bag 2 Sehithwa Tel: 5448140 Fax: 5448139 Tel: 6213756 Fax: 6213240 Tel: 6872105/123 each constituency for use by a Member of Parliament (MP) to carry out his or Fax: 6872106 her Parliamentary work in the constituency. It is a formal and politically neutral Nkange Okavango Palapye place where a Member of Parliament and constituents can meet and discuss P/Bag 3 Tutume P O Box 69 Shakawe P O Box 10582 Palapye developmental issues. Tel: 2987717 Fax: 2987293 Tel: 6875257/230 Tel: 4923475 Fax: 4924231 Fax: 6875258 The offices must be treated strictly as Parliamentary offices and must therefore Ramotswa Sefhare-Ramokgonami Selibe Phikwe East be used for Parliamentary business and not political party business. -

The Decline in the Role of Chieftainship in Elections Geoffrey Barei Democracy Research Project University of Botswana

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies, Vol.14 No,1 (2000) The decline in the role of chieftainship in elections Geoffrey Barei Democracy Research Project University of Botswana Abstract This article focuses on three districts of Botswana, namely Central District, Ngwaketse District and Kgatleng District. It argues that as a result of the role played by the institution of chieftainship in elections, certain voting paltems that are discussed in the conceptual framework can be associated with it. The extent to which chieftainship has influenced electoral outcomes varies from one area to another. Introduction Chieftainship was the cornerstone of Botswana's political life, both before and during the colonial era, After independence in 1966 the institution underwent drastic reforms in terms of role, influence and respect Despite the introduction of a series of legislation by the post-colonial government that has curtailed and eroded the power of chiefs, it still plays a crucial role in the lives of ordinary people in rural areas, Sekgoma (1993:413) argues that the reform process that has affected chieftainship so far is irreversible, The government is not under pressure to repeal parts of the Acts that -

The Big Governance Issues in Botswana

MARCH 2021 THE BIG GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN BOTSWANA A CIVIL SOCIETY SUBMISSION TO THE AFRICAN PEER REVIEW MECHANISM Contents Executive Summary 3 Acknowledgments 7 Acronyms and Abbreviations 8 What is the APRM? 10 The BAPS Process 12 Ibrahim Index of African Governance Botswana: 2020 IIAG Scores, Ranks & Trends 120 CHAPTER 1 15 Introduction CHAPTER 2 16 Human Rights CHAPTER 3 27 Separation of Powers CHAPTER 4 35 Public Service and Decentralisation CHAPTER 5 43 Citizen Participation and Economic Inclusion CHAPTER 6 51 Transparency and Accountability CHAPTER 7 61 Vulnerable Groups CHAPTER 8 70 Education CHAPTER 9 80 Sustainable Development and Natural Resource Management, Access to Land and Infrastructure CHAPTER 10 91 Food Security CHAPTER 11 98 Crime and Security CHAPTER 12 108 Foreign Policy CHAPTER 13 113 Research and Development THE BIG GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN BOTSWANA: A CIVIL SOCIETY SUBMISSION TO THE APRM 3 Executive Summary Botswana’s civil society APRM Working Group has identified 12 governance issues to be included in this submission: 1 Human Rights The implementation of domestic and international legislation has meant that basic human rights are well protected in Botswana. However, these rights are not enjoyed equally by all. Areas of concern include violence against women and children; discrimination against indigenous peoples; child labour; over reliance on and abuses by the mining sector; respect for diversity and culture; effectiveness of social protection programmes; and access to quality healthcare services. It is recommended that government develop a comprehensive national action plan on human rights that applies to both state and business. 2 Separation of Powers Political and personal interests have made separation between Botswana’s three arms of government difficult. -

Download Publication

Impact Report 2020 The IPU The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) is the global organization of national parliaments. It was founded in 1889 as the first multilateral political organization in the world, encouraging cooperation and dialogue between all nations. Today, the IPU comprises 179 national member parliaments and 13 regional parliamentary bodies. It promotes democracy, helps parliaments become stronger, younger, gender-balanced and more diverse. It also defends the human rights of parliamentarians through a dedicated committee made up of MPs from around the world. Twice a year, the IPU convenes over 1,500 delegates and MPs in a world assembly, bringing a parliamentary dimension to the work of the United Nations and the implementation of the 2030 global goals. Cover: The Swiss Parliament adapted to the pandemic by introducing partitions between seats and obligatory facemasks for its members. © Fabrice COFFRINI/AFP Contents Foreword 4 OBJECTIVE 1 Build strong, democratic parliaments 6 OBJECTIVE 2 Advance gender equality and respect for women’s rights 10 OBJECTIVE 3 Protect and promote human rights 14 OBJECTIVE 4 Contribute to peacebuilding, conflict prevention and security 18 OBJECTIVE 5 Promote inter-parliamentary dialogue and cooperation 22 OBJECTIVE 6 Youth empowerment 26 OBJECTIVE 7 Mobilize parliaments around the global development agenda 30 OBJECTIVE 8 Bridge the democracy gap in international relations 34 Towards universal membership 38 Resource mobilization: How the IPU is funded? 39 IPU specialized meetings in 2020 40 Financial results 42 3 Adapting, assisting our Members and accelerating the IPU’s digital transformation 2020 was a game-changer for the IPU. Starting in March, the IPU had to completely reinvent itself to mitigate the effects of the pandemic on its activities. -

DSE Suid-Afrikaanse INSTITUUT VAN INTERNASIONALE AANGELEENTHEDE the SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE of INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS

DSE SUiD-AFRiKAANSE INSTITUUT VAN INTERNASIONALE AANGELEENTHEDE THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Jan Smuts House/-Huis P.O. Box/Posbus 31596 1 Jan Smuts Avenue/Laan 1 2017 Braamfontein Braamfontein, Johannesburg South Africa/Suid-Afrika Tel: 39-2021/22/23 T.A. 'Insintaff' Johannesburg Brief Report Tfo. 40 Not for Publication BOTSWANA PKCEOT HISTORY AND CUPPENT DEVELOPMENTS Botswana,1 one of South Africa's closest neighbours, has recently been subject to some press interest. At the end of "Wl, the focus was on Botswana's military capability and the Possibility that Botswana had received arms from the Soviet Union. In May this year, it was reported that Botswana's President, Dr Ouett Masire, had declared a State of anergency in the face of widespread drought in Botswana. This Brief Report deals with recent developments in Botswana and is divided into : 1) Background Information and Statistics 2) Political Background 3) Economic Developments 4) Poreicm Policy Issues 5) An Assessment — 2 — 1. BACKGROUND BSIFOPMfiTION AMD STATISTICS Political Status % Formerly the British Protectorate of Bechuanaland and one of the three High Commission Territories, gained independence from Britain on 30 September 1966, under the .leadership of the late Sir Seretse Khama. Present Ruling Party - Within a Multi-Party system is the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP). President • Dr Quett Masire, who took office on 13 -July 19£0? is an Executive President and also Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces. The National Assembly % legislative newer vested in the 36-member National Assembly and 15-member Advisory Rouse of Chiefs. Life of Assembly is 5 years„ Population, s. -

Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy the University of Leeds the Candidate Confi

COMBATTING CORRUPTION IN SOUTHERN AFRICA: AN EXAMINATION OF ANTI-CORRUPTION AGENCIES IN BOTSWANA, SOUTH AFRICA AND NAMIBIA By DAVID SEBUDUBLTDU Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Institute for Politics and International Studies August 2002 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas beenmade to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understandingthat it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgments I have always been consciousof my debts to a lot of people in writing this piece of work. I wish to expressmy sincere thanks to all those who played impoftant roles in producing this work. In particular, I am grateful to my supervisors, Dr. Morris Szeftel and Dr. Ray Bush for their professional and personal advice. This thesis would not have been possible without their constant encouragementand support. My thanks go also to the Institute for Politics and International Studies and Ms Caroline Wise for their support in many ways. I would also like to thank all those who cooperatedwith me during my fieldwork in Botswana,Namibia and South Africa; in particular, the Director of the Directorate on Corruption and Economic Crime (DCEC) in Botswana and his staff; the Ombudsman and her staff in Namibia; and in South Affica, The Public Protector and his Staff, The Director of the Investigating Directorate for SerousEconomic Offences (IDSEO) and his staff, and the head of the Special Investigating Unit and his staff. -

His Excellency

International Day of Democracy Parliamentary Conference on Democracy in Africa organized jointly by the Inter-Parliamentary Union and the Parliament of Botswana Gaborone, Botswana, 14 – 16 September 2009 SUMMARY RECORDS DIRECTOR OF CEREMONY (MRS MONICA MPHUSU): His Excellency the President of Botswana, Lieutenant General Seretse Khama Ian Khama, IPU President, Dr Theo-Ben Gurirab, Deputy Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Ms Thokozani Khupe, Former President of Togo Mr Yawovi Agboyibo, Members of the diplomatic community, President and founder of Community Development Foundation Ms Graça Machel, Honourable Speakers, Cabinet Ministers, Permanent Secretary to the President, Honourable Members of Parliament, Dikgosi, if at all they are here, Distinguished Guests. I wish to welcome you to the Inter-Parliamentary Union Conference. It is an honour and privilege to us as a nation to have been given the opportunity to host this conference especially during our election year. This conference comes at a time when local politicians are criss-crossing the country as the election date approaches. They are begging the general public to employ them. They want to be given five year contract. Your Excellencies, some of you would have observed from our local media how vibrant and robust our democracy is. This demonstrates the political maturity that our society has achieved over the past 43 years since we attained independence. Your Excellencies, it is now my singular honour and privilege to introduce our host, the Speaker of the National Assembly of the Republic -

Interview with Former President of Botswana Quett Masire

APPENDIX 4 Interview with Quett Masire, former President of Botswana (1980-1998) Interviewer: Nathaniel Cogley (Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Political Science, Yale University) October 5th, 2010 Gaborone, Botswana NC: Good, so to begin Mr. President I’d like to thank you for your time, taking the time out to participate in this documentary and dissertation work on rethinking what motivates leaders in Africa. And having read your book, I know this will be a fantastic interview. And we really appreciate your time at Yale University. QM: Thank you, sir. NC: Mr. President, your autobiography Very Brave or Very Foolish?: Memoirs of an African Democrat was first published in 2006 and provides a detailed behind-the-scenes account of your personal career and the corresponding decision-making process that ensured Botswana’s rise from a relatively neglected British protectorate to the political and economic success story that we see today. Can you please explain what motivated you, following your retirement from the presidency in 1998, to want to release this book and what audience are you hoping to reach by doing so, both now and in the future? QM: Well, I think, um, one thing that motivated me was the situation was changing so fast and so dramatically that my fear was that the next generation would never know what we once were and they would need to have somebody who could have recorded at least part of what life was like in those days and what methods were tried to try to extricate ourselves from the position in which we found ourselves. -

The Discourse of Tribalism in Botswana's 2019 General Elections

The Discourse of Tribalism in Botswana’s 2019 General Elections Christian John Makgala ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5984-5153 Andy Chebanne ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5393-1771 Boga Thura Manatsha ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5573-7796 Leonard L. Sesa ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6406-5378 Abstract Botswana’s much touted peaceful Presidential succession experienced uncertainty after the transition on 1 April 2019 as a result of former President Ian Khama’s public fallout with his ‘handpicked’ successor, President Mokgweetsi Masisi. Khama spearheaded a robust campaign to dislodge Masisi and the long-time ruling Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) from power. He actively assisted in the formation of a new political party, the Botswana Patriotic Front (BPF). Khama also mobilised the country’s most populous Central District, the Bangwato tribal territory, of which he is kgosi (paramount chief), for the hotly contested 2019 general elections. Two perspectives emerged on Khama’s approach, which was labelled loosely as ‘tribalism’. One school of thought was that the Westernised and bi-racial Khama was not socialised sufficiently into Tswana culture and tribal life to be a tribalist. Therefore, he was said to be using cunningly a colonial-style strategy of divide- and-rule to achieve his agenda. The second school of thought opined that Khama was a ‘shameless tribalist’ hell-bent on stoking ‘tribalism’ among the ‘Bangwato’ in order to bring Masisi’s government to its knees. This article, Alternation Special Edition 36 (2020) 210 - 249 210 Print ISSN 1023-1757; Electronic ISSN: 2519-5476; DOI https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2020/sp36a10 The Discourse of Tribalism in Botswana’s 2019 General Elections however, observes that Khama’s approach was not entirely new in Botswana’s politics, but only bigger in scale, and instigated by a paramount chief and former President. -

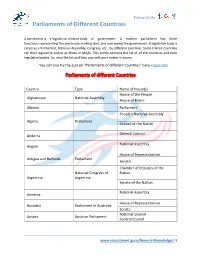

Parliaments of Different Countries

Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries A parliament is a legislative, elected body of government. A modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government. A legislative body is called as a Parliament, National Assembly, Congress, etc., by different countries. Some Islamic countries call their legislative bodies as Shora or Majlis. This article contains the list of all the countries and their legislative bodies. So, read the list and help yourself score better in exams. You can also try the quiz on “Parliaments of different Countries” here – Quiz Link Parliaments of different Countries Country Type Name of house(s) House of the People Afghanistan National Assembly House of Elders Albania Parliament People's National Assembly Algeria Parliament Council of the Nation General Council Andorra National Assembly Angola House of Representatives Antigua and Barbuda Parliament Senate Chamber of Deputies of the National Congress of Nation Argentina Argentina Senate of the Nation National Assembly Armenia House of Representatives Australia Parliament of Australia Senate National Council Austria Austrian Parliament Federal Council www.recruitment.guru/General-Knowledge/|1 Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries Azerbaijan National Assembly House of Assembly Bahamas, The Parliament Senate Council of Representatives Bahrain National Assembly Consultative Council National Parliament Bangladesh House of Assembly Barbados Parliament Senate House of Representatives National Assembly -

Of the Eleventh Parliament

DAILY YOUR VOICE IN PARLIAMENT THETHE SECOND FIRST MEETING MEETING OF THE O SECONDF THE FIFTH SESSION SESSION OF THE OF THE ELEVENTWELFTH PARLIAMENTTH PARLIAMENT THURSDAY 12 NOVEMBER 2020 MIXEDENGLISH VERSION VERSION HANSARDHANSARD NO. NO: 193 200 DISCLAIMER Unocial Hansard This transcript of Parliamentary proceedings is an unocial version of the Hansard and may contain inaccuracies. It is hereby published for general purposes only. The nal edited version of the Hansard will be published when available and can be obtained from the Assistant Clerk (Editorial). THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SPEAKER The Hon. Phandu T. C. Skelemani PH, MP. DEPUTY SPEAKER The Hon. Mabuse M. Pule, MP. (Mochudi East) Clerk of the National Assembly - Ms B. N. Dithapo Deputy Clerk of the National Assembly - Mr L. T. Gaolaolwe Learned Parliamentary Counsel - Ms M. Mokgosi Assistant Clerk (E) - Mr R. Josiah CABINET His Excellency Dr M. E. K. Masisi, MP. - President His Honour S. Tsogwane, MP. (Boteti West) - Vice President Minister for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Hon. K. N. S. Morwaeng, MP. (Molepolole South) - Administration Hon. K. T. Mmusi, MP. (Gabane-Mmankgodi) - Minister of Defence, Justice and Security Hon. Dr L. Kwape, MP. (Kanye South) - Minister of International Affairs and Cooperation Hon. E. M. Molale, MP. (Goodhope-Mabule ) - Minister of Local Government and Rural Development Hon. K. S. Gare, MP. (Moshupa-Manyana) - Minister of Agricultural Development and Food Security Minister of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation Hon. P. K. Kereng, MP. (Specially Elected) - and Tourism Hon. Dr E. G. Dikoloti MP. (Mmathethe-Molapowabojang) - Minister of Health and Wellness Hon. T.M. Segokgo, MP.