Tracing the Tibetan Term Dkor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Times of Mingyur Peldrön: Female Leadership in 18Th Century Tibetan Buddhism

The Life and Times of Mingyur Peldrön: Female Leadership in 18th Century Tibetan Buddhism Alison Joyce Melnick Ann Arbor, Michigan B.A., University of Michigan, 2003 M.A., University of Virginia, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia August, 2014 ii © Copyright by Alison Joyce Melnick All Rights Reserved August 2014 iii Abstract This dissertation examines the life of the Tibetan nun Mingyur Peldrön (mi 'gyur dpal sgron, 1699-1769) through her hagiography, which was written by her disciple Gyurmé Ösel ('gyur med 'od gsal, b. 1715), and completed some thirteen years after her death. It is one of few hagiographies written about a Tibetan woman before the modern era, and offers insight into the lives of eighteenth century Central Tibetan religious women. The work considers the relationship between members of the Mindröling community and the governing leadership in Lhasa, and offers an example of how hagiographic narrative can be interpreted historically. The questions driving the project are: Who was Mingyur Peldrön, and why did she warrant a 200-folio hagiography? What was her role in her religious community, and the wider Tibetan world? What do her hagiographer's literary decisions tell us about his own time and place, his goals in writing the hagiography, and the developing literary styles of the time? What do they tell us about religious practice during this period of Tibetan history, and the role of women within that history? How was Mingyur Peldrön remembered in terms of her engagement with the wider religious community, how was she perceived by her followers, and what impact did she have on religious practice for the next generation? Finally, how and where is it possible to "hear" Mingyur Peldrön's voice in this work? This project engages several types of research methodology, including historiography, semiology, and methods for reading hagiography as history. -

Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition

REVISED EDITION John Powers ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 1 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 2 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 3 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism revised edition by John Powers Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york • boulder, colorado ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 4 Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 • Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 • www.snowlionpub.com © 1995, 2007 by John Powers All rights reserved. First edition 1995 Second edition 2007 No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. Designed and typeset by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Powers, John, 1957- Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism / by John Powers. — Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-55939-282-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-55939-282-7 (alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—China—Tibet. 2. Tibet (China)—Religion. I. Title. BQ7604.P69 2007 294.3’923—dc22 2007019309 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 5 Table of Contents Preface 11 Technical Note 17 Introduction 21 Part One: The Indian Background 1. Buddhism in India 31 The Buddha 31 The Buddha’s Life and Lives 34 Epilogue 56 2. Some Important Buddhist Doctrines 63 Cyclic Existence 63 Appearance and Reality 71 3. Meditation 81 The Role of Meditation in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism 81 Stabilizing and Analytical Meditation 85 The Five Buddhist Paths 91 4. -

AN Introduction to MUSIC to DELIGHT ALL the SAGES, the MEDICAL HISTORY of DRAKKAR TASO TRULKU CHOKYI WANGCRUK (1775-1837)’

I AN iNTRODUCTION TO MUSIC TO DELIGHT ALL THE SAGES, THE MEDICAL HISTORY OF DRAKKAR TASO TRULKU CHOKYI WANGCRUK (1775-1837)’ STACEY VAN VLEET, Columbia University On the auspicious occasion of theft 50th anniversary celebration, the Dharamsala Men-tsee-khang published a previously unavailable manuscript entitled A Briefly Stated framework ofInstructions for the Glorious field of Medicine: Music to Delight All the Sages.2 Part of the genre associated with polemics on the origin and development of medicine (khog ‘bubs or khog ‘bugs), this text — hereafter referred to as Music to Delight All the Sages — was written between 1816-17 in Kyirong by Drakkar Taso Truilcu Chokyi Wangchuk (1775-1837). Since available medical history texts are rare, this one represents a new source of great interest documenting the dynamism of Tibetan medicine between the 1 $th and early 19th centuries, a lesser-known period in the history of medicine in Tibet. Music to Delight All the Sages presents a historical argument concerned with reconciling the author’s various received medical lineages and traditions. Some 1 This article is drawn from a more extensive treatment of this and related W” and 1 9th century medical histories in my forthcoming Ph.D. dissertation. I would like to express my deep gratitude to Tashi Tsering of the Amnye Machen Institute for sharing a copy of the handwritten manuscript of Music to Delight All the Sages with me and for his encouragement and assistance of this work over its duration. This publication was made possible by support from the Social Science Research Council’s International Dissertation Research Fellowship, with funds provided by the Andrew W. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/29/2021 04:56:12PM Via Free Access 76 Cζaja

asian medicine 8 (2013) 75–105 brill.com/asme On the History of Refining Mercury in Tibetan Medicine Olaf Czaja University of Leipzig, Germany [email protected] Abstract In this brief study, the origin and spread of the alchemical process of refining mercury in Tibetan medicine will be explored. Beginning with early sources from the eighth to the twelfth centuries, it will be argued that Orgyenpa Rinchenpel (O rgyan pa Rin chen dpal) caused a turning-point in the processing of mercury in Tibet by introducing a complex alchemical process previously unknown. This knowledge, including the manu- facturing of new pills containing mercury, soon spread through Tibet and was incorpo- rated into the medical expertise of local schools such as the Drangti school (Brang ti). Later it was most prominently practised by Nyamnyi Dorjé (Mnyam nyid rdo rje) in southern Tibet. This particular tradition was upheld by Chökyi Drakpa (Chos kyi grags pa) of the Drigung school, who taught it to his gifted student Könchok Dropen Wangpo (Dkon mchog ’gro phan dbang po). During the seventeenth century, two main transmis- sion lines for refining mercury emerged, one associated with the Gelukpa school (Dge lugs pa) in Central Tibet and one with the Kagyüpa school (Bka’ brgyud pa) and the Rimé movement (Ris med) in eastern Tibet. Both will be discussed in detail, highlight- ing important proponents and major events in their development. Finally, the situation in the twentieth century will be briefly explained. Keywords Tibetan medicine – Tibetan medical history – mercury -

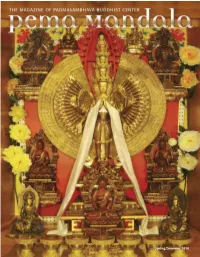

Spring/Summer 2010 in This Issue

Spring/Summer 2010 In This Issue 1 Letter from the Venerable Khenpo Rinpoches 2 Brilliant Lotus Garland of Glorious Wisdom A Glimpse into the Ancient Lineage of Khenchen Palden Volume 9, Spring/Summer 2010 Sherab Rinpoche A Publication of 6 Entrusted: The Journey of Khenchen Rinpoche’s Begging Bowl Padmasambhava Buddhist Center 9 Fulfillment of Wishes: Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism Eight Great Stupas & Five Dhyani Buddhas Founding Directors 12 How I Met the Khenpo Rinpoches Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 14 Schedule of Teachings 16 The Activity Samayas of Anuyoga Ani Lorraine, Co-Editor An Excerpt from the 2009 Shedra, Year 7: Anuyoga Pema Dragpa, Co-Editor Amanda Lewis, Assistant Editor 18 Garland of Views Pema Tsultrim, Coordinator Beth Gongde, Copy Editor 24 The Fruits of Service Michael Ray Nott, Art Director 26 2009 Year in Review Sandy Mueller, Production Editor PBC and Pema Mandala Office For subscriptions or contributions to the magazine, please contact: Padma Samye Ling Attn: Pema Mandala 618 Buddha Highway Sidney Center, NY 13839 (607) 865-8068 [email protected] Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately for Cover: 1,000 Armed Chenrezig statue with the publication in a magazine representing the Five Dhyani Buddhas in the Shantarakshita Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Library at Padma Samye Ling Please email submissions to Photographed by Amanda Lewis [email protected]. © Copyright 2010 by Padmasambhava Buddhist Center International. Material in this publication is copyrighted and may not be reproduced by photocopy or any other means without obtaining written permission from the publisher. -

Constituting Canon and Community in Eleventh Century Tibet: the Extant Writings of Rongzom and His Charter of Mantrins (Sngags Pa’I Bca’ Yig)

religions Article Constituting Canon and Community in Eleventh Century Tibet: The Extant Writings of Rongzom and His Charter of Mantrins (sngags pa’i bca’ yig) Dominic Sur Department of History, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-0710, USA; [email protected] Academic Editors: Michael Sheehy and Joshua Schapiro Received: 2 September 2016; Accepted: 1 March 2017; Published: 15 March 2017 Abstract: This paper explores some of the work of Rongzom Chökyi Zangpo (hereafter Rongzom) and attempts to situate his pedagogical influence within the “Old School” or Nyingma (rnying ma) tradition of Tibetan Buddhism1. A survey of Rongzom’s extant writings indicates that he was a seminal exegete and a particularly important philosopher and interpreter of Buddhism in Tibet. He was an influential intellectual flourishing in a period of cultural rebirth, when there was immense skepticism about Tibetan compositions. His work is thereby a source of insight into the indigenous Tibetan response to the transformations of a renaissance-era in which Indian provenance became the sine qua none of religious authority. Rongzom’s “charter” (bca’ yig), the primary focus of the essay, is an important document for our understanding of Old School communities of learning. While we know very little of the social realities of Old School communities in Rongzom’s time, we do know that they were a source of concern for the emerging political and religious authorities in Western Tibet. As such, the review below argues that the production of the charter should be seen, inter alia, as an effort at maintaining autonomy in the face of a rising political power. -

TSEWANG LHAMO (D. 1812)* Jann Ronis Rom the Earliest Recorded Times, Individual Tibetan Women Have Occasionally Wielded Great Po

POWERFUL WOMEN IN THE HISTORY OF DEGÉ: REASSESSING THE EVENTFUL REIGN OF THE DOWAGER QUEEN TSEWANG LHAMO (D. 1812)* Jann Ronis rom the earliest recorded times, individual Tibetan women have occasionally wielded great political and social power, F and have even bore feminised versions of the highest royal titles in the land. For instance, during the Imperial Period more than one woman in the royal family was called a sitting empress, tsenmo (btsan mo), and several others are immortalised in documents from Dunhuang for their important roles in government, maintenance of the royal family, and patronage of religion.1 Tantalizing, albeit disappointingly brief, snippets of narratives and official documents are all that remain in the historical record for most of the powerful women in Tibetan history, unfortunately. Not a single free-standing biographical work of a Tibetan ruling lady authored during the pre- modern period has ever come to light and, generally speaking, the best scholars can hope for are passing remarks about a given woman in two or three contemporaneous works. This paper explores the life and contested representations of one of the few relatively well- documented Tibetan female political leaders of the pre- and early- modern periods. Tsewang Lhamo (Tshe dbang lha mo, d. 1812) ruled the powerful Tibetan kingdom of Degé (Sde dge) for nearly two decades at the turn of the nineteenth century. However, before the full range of Tibetan sources now available had been published, biased profiles of Tsewang Lhamo in influential Western-language writings made this queen one of the most notorious women in the European and American narrative of Tibetan history. -

Introduction

Introduction The Philosophical Grounds and Literary History of Zhentong Klaus-Dieter Mathes and Michael R. Sheehy Though the subject of emptiness śūnyatā( , stong pa nyid) is relatively well estab- lished in English-language texts on Buddhism, it is usually presented only as the emptiness of lacking independent existence or, more literally, the emptiness of an own nature (svabhāva, rang bzhin). However, the general reader of English literature on Buddhism may not be aware that such an understanding of emptiness reflects a particular interpretation of it, advanced predominantly by the Sakya, Kadam, and Geluk orders, which has exercised a particularly strong influence on the dis- semination of Buddhist studies and philosophy in the West. In Tibetan discourse, this position is referred to as rangtong (rang stong), which means that everything, including the omniscience of a Buddha, is taken to be empty of an own nature. It is this lack of independent, locally determined building blocks of the world that allows in Madhyamaka the Buddhist axiom of dependent origination. In other words, rangtong emptiness is the a priori condition for a universe full of open, dynamic systems. The union of dependent origination and emptiness—the insepa- rability of appearance and emptiness—sets the ground for philosophical models of interrelatedness that are increasingly used in attempts to accommodate astonishing observations being made in the natural sciences, such as wave-particle duality or quantum entanglement. Throughout the long intellectual history of Indian and Tibetan Buddhism, one of the major questions that remains unresolved is whether a systematic pre- sentation of the Buddha’s doctrine requires challenging rangtong as the exclusive mode of emptiness, which has led some to distinguish between two modes of emptiness: (1) Rangtong (rang stong), that is, being empty of an own nature on the one hand, and (2) Zhentong (gzhan stong), that is, being empty of everything other 1 © 2019 State University of New York Press, Albany 2 Klaus-Dieter Mathes and Michael R. -

Namgyal Institute of Tibetology Gangtok, Sikkim

VOLUME 48 NO. 2 2012 NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK, SIKKIM 0. Bulletin of Tibetology 2012 [Contents] Vol.48 No. 2.indd 1 20/08/13 11:11 AM Patron HIS EXCELLENCY SHRI BALMIKI PRASAD SINGH, THE GOVERNOR OF SIKKIM Advisor TASHI DENSAPA, DIRECTOR NIT Editorial Board FRANZ-KARL EHRHARD ACHARYA SAMTEN GYATSO SAUL MULLARD BRIGITTE STEINMANN TASHI TSERING MARK TURIN ROBERTO VITALI Editor ANNA BALIKCI-DENJONGPA Guest Editor for the Present Issue ROBERTO VITALI Assistant Editors TSULTSEM GYATSO ACHARYA THUPTEN TENZING Typesetting: Gyamtso (AMI, DHARAMSHALA) The Bulletin of Tibetology is published bi-annually by the Director, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok, Sikkim. Annual subscription rates: South Asia Rs 150, Oversea $20. Correspondence concerning Bulletin subscriptions, changes of address, missing issues etc. to: Administrative Officer, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok 737102, Sikkim, India ([email protected]). Editorial correspondence should be sent to the Editor at the same address. Submission guidelines. We welcome submission of articles on any subject on the religion, history, language, art and culture of the people of the Tibetan cultural area and the Buddhist Himalaya. Articles should be in English or Tibetan, submitted by email or on CD along with a hard copy and should not exceed 5,000 words in length. The views expressed in the Bulletin of Tibetology are those of the contributors alone and not of the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology. An article represents the view of the author and does not reflect those of any office or institution with which the author may be associated. PRINTED IN INDIA AT ARCHANA ADVERTISING Pvt. Ltd., NEW DELHI 0. -

The Family and Legacy of the Early Northern Treasure Tradition

Journal of Global Buddhism Vol. 16 (2015): 126-143 Research Article The Family and Legacy of the Early Northern Treasure Tradition Jay Valentine, Troy University The Northern Treasure Tradition is well known as the scriptural and ritual platform for Dorjé Drak Monastery in Central Tibet. The historical accounts of this lineage most often focus on the exploits of the tradition's founder, Gödem Truchen (1337 -1409), and his successive incarnations seated at Dorjé Drak Monastery. In this article, the biographical sources are revisited to produce a complementary interpretation of the early history of the tradition. The investigation focuses on the web of family and clan relationships that supports this community of lay practitioners through the late-fourteenth and fifteenth centuries and highlights the contributions of several unsung matriarchs and patriarchs of the Northern Treasure Tradition. This article also contributes to the ongoing study of the gradual development of the institution of rule by incarnation within the Nyingmapa Treasure Traditions through an analysis of the life of Sangyé Pelzang (15th c.), the first of the lineage to buttress his authority through claims of reincarnation. Keywords: Tibetan Buddhism; Northern Treasure Tradition; Jangter byang gter; family n the context of Tibetan Buddhism, the authority and effectiveness of each religious tradition are maintained through careful preservation of lineage. As a result, Tibetan religious historiography tends to focus on the individuals who are the common Ispirit ual ancestors of each of the major traditions. The histories of the treasure traditions likewise feature those individuals who revealed the scriptural wealth that gives each lineage its unique character. -

An Introduction to Music to Delight All the Sages, the Medical History of Drakkar Taso Trulku Chökyi Wangchuk (1775-1837)1

AN INTRODUCTION TO MUSIC TO DELIGHT ALL THE SAGES 55 AN INTRODUCTION TO MUSIC TO DELIGHT ALL THE SAGES, THE MEDICAL HISTORY OF DRAKKAR TaSO TRULKU CHÖKYI WANGCHUK (1775-1837)1 STACEY VAN VLEET, Columbia University On the auspicious occasion of their 50th anniversary celebration, the Dharamsala Men-tsee-khang published a previously unavailable manuscript entitled A Briefly Stated Framework of Instructions for the Glorious Field of Medicine: Music to Delight All the Sages.2 Part of the genre associated with polemics on the origin and development of medicine (khog ’bubs or khog ’bugs), this text – hereafter referred to as Music to Delight All the Sages – was written between 1816-17 in Kyirong by Drakkar Taso Trulku Chökyi Wangchuk (1775-1837).3 Since available medical history texts are rare, this one represents a new source of great interest documenting the dynamism of Tibetan medicine between the 18th and early 19th centuries, a lesser-known period in the history of medicine in Tibet. Music to Delight All the Sages presents a historical argument concerned with reconciling the author’s various received medical lineages and traditions. Some 1 This article is drawn from a more extensive treatment of this and related 18th and 19th century medical histories in my forthcoming Ph.D. dissertation. I would like to express my deep gratitude to Tashi Tsering of the Amnye Machen Institute for sharing a copy of the handwritten manuscript of Music to Delight All the Sages with me and for his encouragement and assistance of this work over its duration. This publication was made possible by support from the Social Science Research Council’s International Dissertation Research Fellowship, with funds provided by the Andrew W. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title An Introduction to 'Music to Delight All the Sages,' the Medical History of Drakkar Taso Trulku Chökyi Wangchuk (1775-1837) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4vz1s49j Journal Bulletin of Tibetology, 48(2) Author Van Vleet, Stacey Publication Date 2012 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California I AN iNTRODUCTION TO MUSIC TO DELIGHT ALL THE SAGES, THE MEDICAL HISTORY OF DRAKKAR TASO TRULKU CHOKYI WANGCRUK (1775-1837)’ STACEY VAN VLEET, Columbia University On the auspicious occasion of theft 50th anniversary celebration, the Dharamsala Men-tsee-khang published a previously unavailable manuscript entitled A Briefly Stated framework ofInstructions for the Glorious field of Medicine: Music to Delight All the Sages.2 Part of the genre associated with polemics on the origin and development of medicine (khog ‘bubs or khog ‘bugs), this text — hereafter referred to as Music to Delight All the Sages — was written between 1816-17 in Kyirong by Drakkar Taso Truilcu Chokyi Wangchuk (1775-1837). Since available medical history texts are rare, this one represents a new source of great interest documenting the dynamism of Tibetan medicine between the 1 $th and early 19th centuries, a lesser-known period in the history of medicine in Tibet. Music to Delight All the Sages presents a historical argument concerned with reconciling the author’s various received medical lineages and traditions. Some 1 This article is drawn from a more extensive treatment of this and related W” and 1 9th century medical histories in my forthcoming Ph.D. dissertation.