Downloaded from Brill.Com09/29/2021 04:56:12PM Via Free Access 76 Cζaja

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Times of Mingyur Peldrön: Female Leadership in 18Th Century Tibetan Buddhism

The Life and Times of Mingyur Peldrön: Female Leadership in 18th Century Tibetan Buddhism Alison Joyce Melnick Ann Arbor, Michigan B.A., University of Michigan, 2003 M.A., University of Virginia, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia August, 2014 ii © Copyright by Alison Joyce Melnick All Rights Reserved August 2014 iii Abstract This dissertation examines the life of the Tibetan nun Mingyur Peldrön (mi 'gyur dpal sgron, 1699-1769) through her hagiography, which was written by her disciple Gyurmé Ösel ('gyur med 'od gsal, b. 1715), and completed some thirteen years after her death. It is one of few hagiographies written about a Tibetan woman before the modern era, and offers insight into the lives of eighteenth century Central Tibetan religious women. The work considers the relationship between members of the Mindröling community and the governing leadership in Lhasa, and offers an example of how hagiographic narrative can be interpreted historically. The questions driving the project are: Who was Mingyur Peldrön, and why did she warrant a 200-folio hagiography? What was her role in her religious community, and the wider Tibetan world? What do her hagiographer's literary decisions tell us about his own time and place, his goals in writing the hagiography, and the developing literary styles of the time? What do they tell us about religious practice during this period of Tibetan history, and the role of women within that history? How was Mingyur Peldrön remembered in terms of her engagement with the wider religious community, how was she perceived by her followers, and what impact did she have on religious practice for the next generation? Finally, how and where is it possible to "hear" Mingyur Peldrön's voice in this work? This project engages several types of research methodology, including historiography, semiology, and methods for reading hagiography as history. -

Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition

REVISED EDITION John Powers ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 1 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 2 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 3 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism revised edition by John Powers Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york • boulder, colorado ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 4 Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 • Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 • www.snowlionpub.com © 1995, 2007 by John Powers All rights reserved. First edition 1995 Second edition 2007 No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. Designed and typeset by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Powers, John, 1957- Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism / by John Powers. — Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-55939-282-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-55939-282-7 (alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—China—Tibet. 2. Tibet (China)—Religion. I. Title. BQ7604.P69 2007 294.3’923—dc22 2007019309 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 5 Table of Contents Preface 11 Technical Note 17 Introduction 21 Part One: The Indian Background 1. Buddhism in India 31 The Buddha 31 The Buddha’s Life and Lives 34 Epilogue 56 2. Some Important Buddhist Doctrines 63 Cyclic Existence 63 Appearance and Reality 71 3. Meditation 81 The Role of Meditation in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism 81 Stabilizing and Analytical Meditation 85 The Five Buddhist Paths 91 4. -

Buddhist Philosophy in Depth, Part 3

WISDOM ACADEMY Buddhist Philosophy in Depth, Part 3 JAY GARFIELD Lessons 6: The Transmission of Buddhism from India to Tibet, and the Shentong-Rangtong Debate Reading: The Crystal Mirror of Philosophical Systems "Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism," pages 71-75 "The Nyingma Tradition," pages 77-84 "The Kagyu Tradition," pages 117-124 "The Sakya Tradition," pages 169-175 "The Geluk Tradition," pages 215-225 CrystalMirror_Cover 2 4/7/17 10:28 AM Page 1 buddhism / tibetan THE LIBRARY OF $59.95US TIBETAN CLASSICS t h e l i b r a r y o f t i b e t a n c l a s s i c s T C! N (1737–1802) was L T C is a among the most cosmopolitan and prolific Tspecial series being developed by e Insti- Tibetan Buddhist masters of the late eighteenth C M P S, by Thuken Losang the crystal tute of Tibetan Classics to make key classical century. Hailing from the “melting pot” Tibetan Chökyi Nyima (1737–1802), is arguably the widest-ranging account of religious Tibetan texts part of the global literary and intel- T mirror of region of Amdo, he was Mongol by heritage and philosophies ever written in pre-modern Tibet. Like most texts on philosophical systems, lectual heritage. Eventually comprising thirty-two educated in Geluk monasteries. roughout his this work covers the major schools of India, both non-Buddhist and Buddhist, but then philosophical large volumes, the collection will contain over two life, he traveled widely in east and inner Asia, goes on to discuss in detail the entire range of Tibetan traditions as well, with separate hundred distinct texts by more than a hundred of spending significant time in Central Tibet, chapters on the Nyingma, Kadam, Kagyü, Shijé, Sakya, Jonang, Geluk, and Bön schools. -

Teachings on Chöd

TEACHINGS ON CHÖD TEACHINGS ON CHÖD #1 - Today you are going to receive Chöd empowerment. Chöd empowerment is something that is going to help on getting rid of all negativities. You have received Tara empowerment. Generally people have the tendency of wanting to be choosy about which Tara empowerment, for example; we talk in terms of white, green and all the rest of it. That is OK, but today when we talk about Chöd, the core of this teaching is nothing else but Tara. Again, we came to the same thing we were talking about Tara, just as the monks when they perform, one item (the mask) will be an aspect of the performance and as soon as the performance is finished they will take off the mask, put another set of costumes and masks. So just like that when you receive Tara empowerment (whether be white or green) it is just a matter of changing costumes. The essence, in the case of the monk’s dances, is the one that is doing all the enacting, one who is behind the masks; the mask changes but the essence doesn’t change. The same is when you receive teachings – sometimes you put on the Tara mask sometime is white, sometime is green ... other times you’ll be putting on Machig Labdröm mask and that is what we will be doing. In the case of the teaching the essence is the Buddha nature. That doesn’t change, all other aspects we put on, the masks, those do change. So today it will be Machig Labchi Drolma. -

AN Introduction to MUSIC to DELIGHT ALL the SAGES, the MEDICAL HISTORY of DRAKKAR TASO TRULKU CHOKYI WANGCRUK (1775-1837)’

I AN iNTRODUCTION TO MUSIC TO DELIGHT ALL THE SAGES, THE MEDICAL HISTORY OF DRAKKAR TASO TRULKU CHOKYI WANGCRUK (1775-1837)’ STACEY VAN VLEET, Columbia University On the auspicious occasion of theft 50th anniversary celebration, the Dharamsala Men-tsee-khang published a previously unavailable manuscript entitled A Briefly Stated framework ofInstructions for the Glorious field of Medicine: Music to Delight All the Sages.2 Part of the genre associated with polemics on the origin and development of medicine (khog ‘bubs or khog ‘bugs), this text — hereafter referred to as Music to Delight All the Sages — was written between 1816-17 in Kyirong by Drakkar Taso Truilcu Chokyi Wangchuk (1775-1837). Since available medical history texts are rare, this one represents a new source of great interest documenting the dynamism of Tibetan medicine between the 1 $th and early 19th centuries, a lesser-known period in the history of medicine in Tibet. Music to Delight All the Sages presents a historical argument concerned with reconciling the author’s various received medical lineages and traditions. Some 1 This article is drawn from a more extensive treatment of this and related W” and 1 9th century medical histories in my forthcoming Ph.D. dissertation. I would like to express my deep gratitude to Tashi Tsering of the Amnye Machen Institute for sharing a copy of the handwritten manuscript of Music to Delight All the Sages with me and for his encouragement and assistance of this work over its duration. This publication was made possible by support from the Social Science Research Council’s International Dissertation Research Fellowship, with funds provided by the Andrew W. -

DRUKPA KAGYUD SCHOOL of TIBETAN BUDDHISM in INDIAN HIMALAYAS: an INTRODUCTION Dr

www.ijcrt.org © 2021 IJCRT | Volume 9, Issue 3 March 2021 | ISSN: 2320-2882 DRUKPA KAGYUD SCHOOL OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM IN INDIAN HIMALAYAS: AN INTRODUCTION Dr. SONAM ZANGPO Assistant Professor, Dept. of Indo-Tibetan Studies, Bhasha-Bhavana, VISVA-BHARATI, Santiniketan, Birbhum, West Bengal Abstract After the decline of traditional Buddhism from the plains and plateaus of Indian territories. Buddhism somehow remained alive in Indian Himalayas with another dimensional names, forms and functions. Which assimilates both traditional and later progressed thoughts of Buddhism and perennial Buddhist lineage practices. In this regard, Tibetan Buddhism is very actively and widely spread as well as sustained in Indian Himalayas. Consequently, Indian Himalayas are very important places for the preservation of distinct Buddhist culture, rich heritage and uninterrupted Nālandā scholars and Tibetan students’ teachings traditions. It conveys the messages of peace, harmony, brotherhood among the other faith followers within the regions and beyond the states of the country. This research paper exclusively gives focus on different features of Drukpa Kagyud (Wyl. ’brug pa bk’ brgyud) School of Tibetan Buddhism in Indian Himalayas. It is based of both primary and secondary sources of the existing literatures as well as some field surveys. Key-Words: Buddhism, Drukpa Kagyud, Tibetan Buddhism, Monasteries, Nunneries, Lama and Rinpoches. Introduction There are many Buddhist centers in Indian Himalayan regions. Here, Indian Himalayas referred to all smaller and larger expanded places and regions as starting from Leh and Kargil in Ladakh, Paddar, Kistwar in Jammu, Pangi, Chamba, Lahual-Spitti, Kullu-Manali, Kinnour, Dharmsala in Himachal Pradesh, Dehradun in Uttarakhand, Darjeeling-Kalimpong in West Bengal, Sikkim, Mon-Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh and so forth. -

Spring/Summer 2010 in This Issue

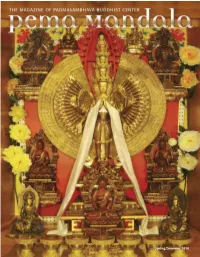

Spring/Summer 2010 In This Issue 1 Letter from the Venerable Khenpo Rinpoches 2 Brilliant Lotus Garland of Glorious Wisdom A Glimpse into the Ancient Lineage of Khenchen Palden Volume 9, Spring/Summer 2010 Sherab Rinpoche A Publication of 6 Entrusted: The Journey of Khenchen Rinpoche’s Begging Bowl Padmasambhava Buddhist Center 9 Fulfillment of Wishes: Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism Eight Great Stupas & Five Dhyani Buddhas Founding Directors 12 How I Met the Khenpo Rinpoches Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 14 Schedule of Teachings 16 The Activity Samayas of Anuyoga Ani Lorraine, Co-Editor An Excerpt from the 2009 Shedra, Year 7: Anuyoga Pema Dragpa, Co-Editor Amanda Lewis, Assistant Editor 18 Garland of Views Pema Tsultrim, Coordinator Beth Gongde, Copy Editor 24 The Fruits of Service Michael Ray Nott, Art Director 26 2009 Year in Review Sandy Mueller, Production Editor PBC and Pema Mandala Office For subscriptions or contributions to the magazine, please contact: Padma Samye Ling Attn: Pema Mandala 618 Buddha Highway Sidney Center, NY 13839 (607) 865-8068 [email protected] Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately for Cover: 1,000 Armed Chenrezig statue with the publication in a magazine representing the Five Dhyani Buddhas in the Shantarakshita Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Library at Padma Samye Ling Please email submissions to Photographed by Amanda Lewis [email protected]. © Copyright 2010 by Padmasambhava Buddhist Center International. Material in this publication is copyrighted and may not be reproduced by photocopy or any other means without obtaining written permission from the publisher. -

2011, Volume 20, Number 1

Winter 2011 Volume 20, Number 1 Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women TABLE OF CONTENTS Sharing Impressions, Meeting Expectations: Evaluating the 12th Sakyadhita Conference Titi Soentoro The Question of Lineage in Tibetan Buddhism: A Woman’s Perspective Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo Lipstick Buddhists and Dharma Divas: Buddhism in the Most Unlikely Packages Lisa J. Battaglia The Anti-Virus Enlightenment Hyunmi Cho Risks and Opportunities of Scholarly Engagement with Buddhism Christine Murphy SHARING IMPRESSIONS, MEETING EXPECTATIONS Evaluating the 12th Sakyadhita Conference Grace Schireson in Interview By Titi Soentoro Janice Tolman Full Ordination for Women and It was a great joy to be among such esteemed scholars, nuns, and laywomen at the 12th Sakyadhita the Fourfold Sangha International Conference on Buddhist Women held in Bangkok from June 12 to 18, 2011. It felt like such Santacitta Bhikkhuni an honor just to be in their company. This feeling was shared by all the participants. Around the general A SeeSaw theme, “Leading to Liberation, the conference addressed many issues of Buddhist women, including Wendy Lin issues that people don’t generally associate with Buddhist women, such as the environment and LGBTQ concerns. Sakyadhita in Cyberspace: Sakyadhita and the Social Media At the end of the conference, participants were asked to share their feelings and insights, and to Revolution offer suggestions for the next Sakyadhita Conference. The evaluations asked which aspects they enjoyed Charlotte B. Collins the most and the least, which panels and workshops they learned the most from, and for suggestions for themes and topics for the next Sakyadhita Conference in India. In many languages, participants shared A Tragic Episode Rebecca Paxton their reflections on all aspects of the conference Further Reading What Participants Appreciated Most Overall, respondents found the conference very interesting and enjoyable. -

Constituting Canon and Community in Eleventh Century Tibet: the Extant Writings of Rongzom and His Charter of Mantrins (Sngags Pa’I Bca’ Yig)

religions Article Constituting Canon and Community in Eleventh Century Tibet: The Extant Writings of Rongzom and His Charter of Mantrins (sngags pa’i bca’ yig) Dominic Sur Department of History, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-0710, USA; [email protected] Academic Editors: Michael Sheehy and Joshua Schapiro Received: 2 September 2016; Accepted: 1 March 2017; Published: 15 March 2017 Abstract: This paper explores some of the work of Rongzom Chökyi Zangpo (hereafter Rongzom) and attempts to situate his pedagogical influence within the “Old School” or Nyingma (rnying ma) tradition of Tibetan Buddhism1. A survey of Rongzom’s extant writings indicates that he was a seminal exegete and a particularly important philosopher and interpreter of Buddhism in Tibet. He was an influential intellectual flourishing in a period of cultural rebirth, when there was immense skepticism about Tibetan compositions. His work is thereby a source of insight into the indigenous Tibetan response to the transformations of a renaissance-era in which Indian provenance became the sine qua none of religious authority. Rongzom’s “charter” (bca’ yig), the primary focus of the essay, is an important document for our understanding of Old School communities of learning. While we know very little of the social realities of Old School communities in Rongzom’s time, we do know that they were a source of concern for the emerging political and religious authorities in Western Tibet. As such, the review below argues that the production of the charter should be seen, inter alia, as an effort at maintaining autonomy in the face of a rising political power. -

TSEWANG LHAMO (D. 1812)* Jann Ronis Rom the Earliest Recorded Times, Individual Tibetan Women Have Occasionally Wielded Great Po

POWERFUL WOMEN IN THE HISTORY OF DEGÉ: REASSESSING THE EVENTFUL REIGN OF THE DOWAGER QUEEN TSEWANG LHAMO (D. 1812)* Jann Ronis rom the earliest recorded times, individual Tibetan women have occasionally wielded great political and social power, F and have even bore feminised versions of the highest royal titles in the land. For instance, during the Imperial Period more than one woman in the royal family was called a sitting empress, tsenmo (btsan mo), and several others are immortalised in documents from Dunhuang for their important roles in government, maintenance of the royal family, and patronage of religion.1 Tantalizing, albeit disappointingly brief, snippets of narratives and official documents are all that remain in the historical record for most of the powerful women in Tibetan history, unfortunately. Not a single free-standing biographical work of a Tibetan ruling lady authored during the pre- modern period has ever come to light and, generally speaking, the best scholars can hope for are passing remarks about a given woman in two or three contemporaneous works. This paper explores the life and contested representations of one of the few relatively well- documented Tibetan female political leaders of the pre- and early- modern periods. Tsewang Lhamo (Tshe dbang lha mo, d. 1812) ruled the powerful Tibetan kingdom of Degé (Sde dge) for nearly two decades at the turn of the nineteenth century. However, before the full range of Tibetan sources now available had been published, biased profiles of Tsewang Lhamo in influential Western-language writings made this queen one of the most notorious women in the European and American narrative of Tibetan history. -

Introduction

Introduction The Philosophical Grounds and Literary History of Zhentong Klaus-Dieter Mathes and Michael R. Sheehy Though the subject of emptiness śūnyatā( , stong pa nyid) is relatively well estab- lished in English-language texts on Buddhism, it is usually presented only as the emptiness of lacking independent existence or, more literally, the emptiness of an own nature (svabhāva, rang bzhin). However, the general reader of English literature on Buddhism may not be aware that such an understanding of emptiness reflects a particular interpretation of it, advanced predominantly by the Sakya, Kadam, and Geluk orders, which has exercised a particularly strong influence on the dis- semination of Buddhist studies and philosophy in the West. In Tibetan discourse, this position is referred to as rangtong (rang stong), which means that everything, including the omniscience of a Buddha, is taken to be empty of an own nature. It is this lack of independent, locally determined building blocks of the world that allows in Madhyamaka the Buddhist axiom of dependent origination. In other words, rangtong emptiness is the a priori condition for a universe full of open, dynamic systems. The union of dependent origination and emptiness—the insepa- rability of appearance and emptiness—sets the ground for philosophical models of interrelatedness that are increasingly used in attempts to accommodate astonishing observations being made in the natural sciences, such as wave-particle duality or quantum entanglement. Throughout the long intellectual history of Indian and Tibetan Buddhism, one of the major questions that remains unresolved is whether a systematic pre- sentation of the Buddha’s doctrine requires challenging rangtong as the exclusive mode of emptiness, which has led some to distinguish between two modes of emptiness: (1) Rangtong (rang stong), that is, being empty of an own nature on the one hand, and (2) Zhentong (gzhan stong), that is, being empty of everything other 1 © 2019 State University of New York Press, Albany 2 Klaus-Dieter Mathes and Michael R. -

The Practice of the SIX YOGAS of NAROPA the Practice of the SIX YOGAS of NAROPA

3/420 The Practice of THE SIX YOGAS OF NAROPA The Practice of THE SIX YOGAS OF NAROPA Translated, edited and introduced by Glenn H. Mullin 6/420 Table of Contents Preface 7 Technical Note 11 Translator's Introduction 13 1 The Oral Instruction of the Six Yogas by the Indian Mahasiddha Tilopa (988-1069) 23 2 Vajra Verses of the Whispered Tradition by the Indian Mahasiddha Naropa (1016-1100) 31 3 Notes on A Book of Three Inspirations by Jey Sherab Gyatso (1803-1875) 43 4 Handprints of the Profound Path of the Six Yogas of Naropa: A Source of Every Realiza- tion by Gyalwa Wensapa (1505-1566) 71 8/420 5 A Practice Manual on the Six Yogas of Naropa: Taking the Practice in Hand by Lama Jey Tsongkhapa (1357-1419) 93 6 The Golden Key: A Profound Guide to the Six Yogas of Naropa by the First Panchen Lama (1568-1662) 137 Notes 155 Glossary: Tibetan Personal and Place Names 167 Texts Quoted 171 Preface Although it is complete in its own right and stands well on its own, this collection of short commentaries on the Six Yogas of Naropa, translated from the Tibetan, was originally conceived of as a companion read- er to my Tsongkhapa's Six Yogas of Naropa (Snow Lion, 1996). That volume presents one of the greatest Tibetan treatises on the Six Yogas system, a text composed by the Tibetan master Lama Jey Tsongkhapa (1357-1419)-A Book of Three Inspirations: A Treatise on the Stages of Training in the Profound Path of Naropa's Six Yogas (Tib.