A Sociological and Statistical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Kin Relationships

In H. T. Reis & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human relationships (pp. 951-954). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Kin Relationships Kin relationships are traditionally defined as ties based on blood and marriage. They include lineal generational bonds (children, parents, grandparents, and great- grandparents), collateral bonds (siblings, cousins, nieces and nephews, and aunts and uncles), and ties with in-laws. An often-made distinction is that between primary kin (members of the families of origin and procreation) and secondary kin (other family members). The former are what people generally refer to as “immediate family,” and the latter are generally labeled “extended family.” Marriage, as a principle of kinship, differs from blood in that it can be terminated. Given the potential for marital break-up, blood is recognized as the more important principle of kinship. This entry questions the appropriateness of traditional definitions of kinship for “new” family forms, describes distinctive features of kin relationships, and explores varying perspectives on the functions of kin relationships. Questions About Definition Changes over the last thirty years in patterns of family formation and dissolution have given rise to questions about the definition of kin relationships. Guises of kinship have emerged to which the criteria of blood and marriage do not apply. Assisted reproduction is a first example. Births resulting from infertility treatments such as gestational surrogacy and in vitro fertilization with ovum donation challenge the biogenetic basis for kinship. A similar question arises for adoption, which has a history 2 going back to antiquity. Partnerships formed outside of marriage are a second example. Strictly speaking, the family ties of nonmarried cohabitees do not fall into the category of kin, notwithstanding the greater acceptance over time of consensual unions both formally and informally. -

Dna by the Entirety

DNA BY THE ENTIRETY Natalie Ram The law fails to accommodate the inconvenient fact that an individual’s identifiable genetic information is involuntarily and immutably shared with her close genetic relatives. Legal institutions have established that individuals have a cognizable interest in control- ling genetic information that is identifying to them. The Supreme Court recognized in Maryland v. King that the Fourth Amendment is impli- cated when arrestees’ DNA is analyzed, and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act protects individuals from genetic discrimination in the employment and health-insurance markets. But genetic infor- mation is not like other forms of private or personal information because it is shared—immutably and involuntarily—in ways that are identifying of both the source and that person’s close genetic relatives. Standard approaches to addressing interests in genetic information have largely failed to recognize this characteristic, treating such infor- mation as individualistic. While many legal frames may be brought to bear on this problem, this Article focuses on the law of property. Specifically, looking to the law of tenancy by the entirety, this Article proposes one possible frame- work for grappling with the overlapping interests implicated in genetic identification and analysis. Tenancy by the entirety, like interests in shared identifiable genetic information, calls for the difficult task of conceptualizing two persons as one. The law of tenancy by the entirety thus provides a useful analytical framework for considering how legal institutions might take interests in shared identifiable genetic infor- mation into account. This Article examines how this framework may shape policy approaches in three domains: forensic identification, genetic research, and personal genetic testing. -

Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles University of Dayton School of Law

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 104 | Issue 3 Article 4 2016 Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles University of Dayton School of Law Shelly Kreiczer-Levy College of Law and Business in Ramat Gan Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Family Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Laufer-Ukeles, Pamela and Kreiczer-Levy, Shelly (2016) "Family Formation and the Home," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 104 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol104/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles' & Shelly Kreiczer-Levj INTRODUCTION' In this article, we consider the relevance of home sharing in family formation. When couples or groups of persons are recognized as families, they are afforded significant benefits and given certain obligations by the law.4 Families have their own category of laws, rights, and obligations.' Currently, the law of family formation and recognition is in a state of flux. Although in some respects the defining legal lines of the family have been well settled for centuries around blood and the formal legal ties of marriage and parenthood, in significant ways, the family form has been fundamentally altered over the past few decades. -

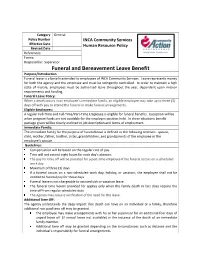

Funeral and Bereavement Leave Benefit Purpose/Introduction Funeral Leave Is a Benefit Extended to Employees of INCA Community Services

Category General Policy Number INCA Community Services Effective Date Human Resource Policy Revised Date References: Forms: Responsible: Supervisor Funeral and Bereavement Leave Benefit Purpose/Introduction Funeral leave is a benefit extended to employees of INCA Community Services. Leave represents money for both the agency and the employee and must be stringently controlled. In order to maintain a high state of morale, employees must be authorized leave throughout the year, dependent upon mission requirements and funding. Funeral Leave Policy: When a death occurs in an employee’s immediate family, an eligible employee may take up to three (3) days off with pay to attend the funeral or make funeral arrangements. Eligible Employees: A regular Full-Time and Full-Time/Part-Time Employee is eligible for funeral benefits. Exception will be when program funds are not available for the employee position held. In these situations benefit package given will be clearly outlined in job description and terms of employment. Immediate Family: The immediate family for the purpose of funeral leave is defined as the following relatives: spouse, child, mother, father, brother, sister, grandchildren, and grandparents of the employee or the employee’s spouse. Guidelines: Compensation will be based on the regular rate of pay. Time will not exceed eight hours for each day’s absence. The pay for time off will be prorated for a part-time employee if the funeral occurs on a scheduled work day. Maximum of three (3) days. If a funeral occurs on a non-scheduled work day, holiday, or vacation, the employee shall not be entitled to funeral pay for those days. -

The Reproductive Decision-Making of Women with Mitochondrial Disease

Julia Tonge Uncertain Existence: The reproductive decision-making of women with Mitochondrial Disease. Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Neuroscience, Newcastle University October 2017 Abstract The aim of this thesis was to understand the process of reproductive decision- making in women with maternally inherited mitochondrial disease. It demonstrates the uncertainty fundamental to the experiences of women with mitochondrial DNA mutations (a subsection of women with mitochondrial disease). This uncertainty manifests in the personal accounts of their condition, as well as in relation to their reproductive decision-making. Twenty semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with eighteen women with mitochondrial DNA mutations, sampled via their connection to a mitochondrial disease specialist service in North East England. Retrospective, prospective and hypothetical questions were utilised in data collection. The data generated from the study, which was informed by constructivist grounded theory, can be organised into two central areas, both of which can be related back to uncertainty. The first area relates to how women harbour the desire for a healthy biologically related child. The second area features decision-making, which within the context of maternally inherited mitochondrial disease, is essentially the process by which women consolidate their desires for healthy children, and how they negotiate risk. The women’s accounts highlight social aspects of uncertainty that features in their reproductive decision-making, in contrast to the current literature that focuses on more clinical aspects of uncertainty. In addition, they also demonstrate how educational and employment institutions struggle to manage the uncertainty inherent in mitochondrial disease. -

Death of Our Stepchild Or Our Partner's Child

Death of our Stepchild or our Partner’s Child A nationwide organisation of bereaved parents and their families offering support after a child dies. Death of our Stepchild or our Partner’s Child The death of a child, no matter their age, causes heartbreak for their parents. This leaflet looks at some of the particular issues that may arise if the child who died was our partner’s biological child but not our own. For other aspects of coping with grief, grief within blended families, and supporting surviving children, please see the list of publications produced by The Compassionate Friends (TCF) at the end of this leaflet. Our grief We live in a society that produces many variations of families, and anyone may find themselves in an active or passive parenting role for those who are not their biological children. The blended family may come about following earlier bereavement, through single parenthood or after separation or divorce, and the stepchildren may live part- or full-time in the new family. We may or may not be one of the child’s legal parents. Even though we do not have a biological or perhaps legal connection, the death of a child within our family circle is still going to be a terrible event. We may recognise within ourselves any of the common grief reactions such as profound sadness, confusion, sleeplessness, lack of concentration, and more. Grief is not orderly or progressive: it pours in causing great emotional turmoil, and is unpredictable in its timing and intensity. It comes in waves and often feels overwhelming. -

Bereavement Leave

STATE OF CALIFORNIA - DEPARTMENT OF GENERAL SERVICE PERSONNEL OPERATIONS MANUAL SUBJECT: BEREAVEMENT LEAVE REPRESENTED EMPLOYEES Bereavement leave allows for up to three (3) eight-hour days (24 hours) per occurrence or three (3) eight-hour days (24 hours) in a fiscal year based on the family member. The following chart describes the family member and bereavement leave allowed per bargaining unit. Bargaining Unit Eligible family member - three (3) eight-hour days Eligible family member - three (3) (24 hours) per occurrence eight-hour days (24 hours) in a fiscal year 1, 4, 11, 14, 15 • Parent • Aunt • Stepparent • Uncle • Spouse • Niece • Domestic Partner • Nephew • Child • immediate family members of • Grandchild Domestic Partners • Grandparent • Brother • Sister • Stepchild • Mother-in-Law • Father-in-Law • Daughter-in-Law • Son-in-Law • Sister-in-Law • Brother-in-Law • any person residing in the immediate household 2 • Parent • Grandchild • Stepparent • Grandparent • Spouse • Aunt • Domestic Partner • Uncle • Child • Niece • Sister • Nephew • Brother • Mother-in-Law • Stepchild • Father-in-Law • any person residing in the immediate household • Daughter-in-Law • Son-in-Law • Sister-in-Law • Brother-in-Law • immediate family member 7 • Parent • Grandchild • Stepparent • Grandparent • Spouse • Aunt • Domestic Partner • Uncle STATE OF CALIFORNIA - DEPARTMENT OF GENERAL SERVICE PERSONNEL OPERATIONS MANUAL Bargaining Unit Eligible family member - three (3) eight-hour days Eligible family member - three (3) (24 hours) per occurrence eight-hour -

R. Brumbaugh Kinship Analysis: Methods, Results and the Sirionó Demonstration Case

R. Brumbaugh Kinship analysis: methods, results and the Sirionó demonstration case In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 134 (1978), no: 1, Leiden, 1-29 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 02:22:46PM via free access ROBERT C. BRUMBAUGH KINSHIP ANALYSIS : METHODS, RESULTS,AND THE SIRIONO DEMONSTRATION CASE A likely exarnple of 'cultural devolution', the Sirionó hunters and gatherers of Bolivia were best known for the whistle-talk they have developed until Needham (1962) drew attention to their kinship system, which he cited as a rare case of matrilineal prescriptive alliance. His interpretation was subsequently weakened as it becarne clear that there is no evidence in the Sirionó ethnography (Holmberg 1950) for social correlates which are an essential part of the 'prescriptive alliance' scheme (Needham 1962, 1964). -Meanwhile Scheffler and Lounsbury had chosen the Sirionó system as the demonstration case for a new approach to kinship, called 'trans- formational analysis', which aims to discover the underlying cognitive structure of the system through semantic analysis. The Sirionó case study (1971) contrasted the results of this method with the failure of Needharn's model; and since prescriptive alliance theory itself is Need- ham's modified version of Lévi-Strauss' kinship theory (which I will cal1 'structural' theory), the case seemed to vindicate their semantic approach where 'structuralism' had already proved inadequate. The purpose of this paper is to compare -

Supporting Stepfamilies Workbook

Tvqqpsujoh! Tufqgbnjmjft Xpslcppl!xjui!Mfttpot!boe Bdujwjujft!gps!Qbsfout!boe!Dijmesfo Lbuiz!S/!Cptdi-!Fyufotjpo!Gbnjmz!Mjgf!Fevdbujpo!Tqfdjbmjtu Dzouijb!S/!Tusbtifjn-!Fyufotjpo!Fevdbups UQBKPFLKFP>FSFPFLKLCQEB KPQFQRQBLCDOF@RIQROB>KA>QRO>IBPLRO@BP>QQEBKFSBOPFQVLC B?O>PH>¨ FK@LIK@LLMBO>QFKDTFQEQEBLRKQFBP>KAQEBKFQBAQ>QBPBM>OQJBKQLCDOF@RIQROB KFSBOPFQVLCB?O>PH>¨ FK@LIKUQBKPFLKBAR@>QFLK>IMOLDO>JP>?FABTFQEQEBKLKAFP@OFJFK>QFLK MLIF@FBPLCQEBKFSBOPFQVLCB?O>PH>¨ FK@LIK>KAQEBKFQBAQ>QBPBM>OQJBKQLCDOF@RIQROB Supporting Stepfamilies Table of Contents Supporting Stepfamilies Workbook. 1 What is a Stepfamily?. 3 Supporting Stepfamilies: What Do the Children Feel?. 26 Activity Sheets. 31 Five Stages of the Grief Cycle . .60 Evaluation Sheet © The Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska. All rights reserved. w Supporting Stepfamilies 60 Supporting Stepfamilies Workbook Do any of these questions sound familiar? Money, housework, and sex are often the Do you ask some of these questions? three major topics couples fight about. Other major conflict areas are time spent • How should we handle discipline? together and issues regarding children. These challenges are often more pronounced • How do I set clear boundaries? when children from previous relationships are brought into a new partnership. These • Can I be friends with my stepchildren? potential challenges, as well as the many benefits of living in a stepfamily, will be • What should I do when my stepchild does discussed in this course. not talk to me? Supporting Stepfamilies may be used as a • How do I interact with my stepchildren’s learn-at-home course for self-study or may other parent? be taught in small groups with a facilitator or teacher. -

Family Registration Form

FAMILY REGISTRATION FORM An NCHA member may allow certain members of his/her immediate family (as defined in that rule) to show a horse owned by that member in NCHA amateur and non- professional events. If the horse owner/member wishes for someone in his/her immediate family to show the horse owner/member’s horse under the provisions of Rule 51.a.4, it is the responsibility of the horse owner/ member to complete this form and file it with the NCHA prior to any show in which an immediate family member will be showing any horse owned by the horse owner/member. Any horse owner/member filing this form is also responsible for filing with the NCHA any updates necessary to insure that this form to is accurate and up to date. If this completed form is not on file with the NCHA, no one other than the horse owner may show that horse in any amateur or non-pro classes. Member/Owner Name: ___________________________ Member #: _______ ___ (Please Print) Horses: Name as it appears on Breed registry: ____________________________________Reg#____________ Name as it appears on Breed registry: ____________________________________Reg#____________ Name as it appears on Breed registry: ____________________________________Reg#____________ IMMEDIATE FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS: Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Date: Signature: ________________________________________________________ RECEIVED BY NCHA: REFERENCE SHEET FOR FAMILY OWNED HORSE RULE The following chart is to assist in the application of the NCHA’s new Family Owned Horse Rule. -

Domestic and International Adoption: Strategies to Improve Behavioral Health Outcomes for Youth and Their Families ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

JANUARY 28, 2015 Domestic and International Adoption: Strategies to Improve Behavioral Health Outcomes for Youth and Their Families ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank the following people for their participation in the planning committee for the Domestic and International Adoption: Strategies to Improve Behavioral Health Outcomes for Youth and Their Families meeting. • Terry Baugh, Kidsave • Heather Burke, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention • Wilson Compton, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health • Angela Drumm, American Institutes for Research • Kelly Fisher, Administration for Children and Families • Robert Freeman, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health • Amy Goldstein, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health • Valerie Maholmes, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health • Sonali Patel, Administration for Children and Families • Eve Reider, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health • Elizabeth Robertson, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health • Lisa Rubenstein, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration • Kate Stepleton, Administration for Children and Families • Phil Wang, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health • Mary Bruce Webb, Administration for Children and Families BACKGROUND On August 29–30, 2012, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)