Deprescribing Supplement May 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

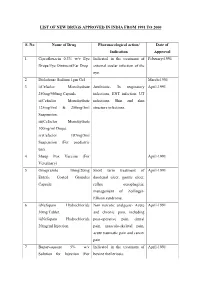

List of New Drugs Approved in India from 1991 to 2000

LIST OF NEW DRUGS APPROVED IN INDIA FROM 1991 TO 2000 S. No Name of Drug Pharmacological action/ Date of Indication Approval 1 Ciprofloxacin 0.3% w/v Eye Indicated in the treatment of February-1991 Drops/Eye Ointment/Ear Drop external ocular infection of the eye. 2 Diclofenac Sodium 1gm Gel March-1991 3 i)Cefaclor Monohydrate Antibiotic- In respiratory April-1991 250mg/500mg Capsule. infections, ENT infection, UT ii)Cefaclor Monohydrate infections, Skin and skin 125mg/5ml & 250mg/5ml structure infections. Suspension. iii)Cefaclor Monohydrate 100mg/ml Drops. iv)Cefaclor 187mg/5ml Suspension (For paediatric use). 4 Sheep Pox Vaccine (For April-1991 Veterinary) 5 Omeprazole 10mg/20mg Short term treatment of April-1991 Enteric Coated Granules duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, Capsule reflux oesophagitis, management of Zollinger- Ellison syndrome. 6 i)Nefopam Hydrochloride Non narcotic analgesic- Acute April-1991 30mg Tablet. and chronic pain, including ii)Nefopam Hydrochloride post-operative pain, dental 20mg/ml Injection. pain, musculo-skeletal pain, acute traumatic pain and cancer pain. 7 Buparvaquone 5% w/v Indicated in the treatment of April-1991 Solution for Injection (For bovine theileriosis. Veterinary) 8 i)Kitotifen Fumerate 1mg Anti asthmatic drug- Indicated May-1991 Tablet in prophylactic treatment of ii)Kitotifen Fumerate Syrup bronchial asthma, symptomatic iii)Ketotifen Fumerate Nasal improvement of allergic Drops conditions including rhinitis and conjunctivitis. 9 i)Pefloxacin Mesylate Antibacterial- In the treatment May-1991 Dihydrate 400mg Film Coated of severe infection in adults Tablet caused by sensitive ii)Pefloxacin Mesylate microorganism (gram -ve Dihydrate 400mg/5ml Injection pathogens and staphylococci). iii)Pefloxacin Mesylate Dihydrate 400mg I.V Bottles of 100ml/200ml 10 Ofloxacin 100mg/50ml & Indicated in RTI, UTI, May-1991 200mg/100ml vial Infusion gynaecological infection, skin/soft lesion infection. -

Tall Man Lettering List REPORT DECEMBER 2013 1

Tall Man Lettering List REPORT DECEMBER 2013 1 TALL MAN LETTERING LIST REPORT WWW.HQSC.GOVT.NZ Published in December 2013 by the Health Quality & Safety Commission. This document is available on the Health Quality & Safety Commission website, www.hqsc.govt.nz ISBN: 978-0-478-38555-7 (online) Citation: Health Quality & Safety Commission. 2013. Tall Man Lettering List Report. Wellington: Health Quality & Safety Commission. Crown copyright ©. This copyright work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 New Zealand licence. In essence, you are free to copy and distribute the work (including other media and formats), as long as you attribute the work to the Health Quality & Safety Commission. The work must not be adapted and other licence terms must be abided. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/nz/ Copyright enquiries If you are in doubt as to whether a proposed use is covered by this licence, please contact: National Medication Safety Programme Team Health Quality & Safety Commission PO Box 25496 Wellington 6146 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Health Quality & Safety Commission acknowledges the following for their assistance in producing the New Zealand Tall Man lettering list: • The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care for advice and support in allowing its original work to be either reproduced in whole or altered in part for New Zealand as per its copyright1 • The Medication Safety and Quality Program of Clinical Excellence Commission, New South -

Package Leaflet: Information for the User Hydroxyzine Bluefish 25 Mg

Package leaflet: Information for the user Hydroxyzine Bluefish 25 mg film-coated tablets hydroxyzine hydrochloride Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start using this medicine because it contains important information for you. - Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. - If you have any further questions, ask your doctor or pharmacist. - This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same as yours. - If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet 1. What Hydroxyzine Bluefish is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you use Hydroxyzine Bluefish 3. How to use Hydroxyzine Bluefish 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Hydroxyzine Bluefish 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Hydroxyzine Bluefish is and what it is used for Hydroxyzine Bluefish blocks histamine, a substance found in body tissues. It is effective against anxiety, itching and urticaria. Hydroxyzine Bluefish is used to treat anxiety in adults itching (pruritus) associated with hives (urticaria) in adults adolescents and children of 5 years and above 2. What you need to know before you take Hydroxyzine Bluefish Do not take Hydroxyzine Bluefish - if you are allergic to hydroxyzine hydrochloride or any of the other ingredients of this medicine (listed in section 6) - if you are allergic (hypersensitive) to cetirizine, aminophylline, ethylenediamine or piperazine derivatives (closely related active substances of other medicines). -

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Cr

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Crizotinib (PF-02341066) 1 4 55 Docetaxel 1 5 98 Anastrozole 1 6 25 Cladribine 1 7 23 Methotrexate 1 8 -187 Letrozole 1 9 65 Entecavir Hydrate 1 10 48 Roxadustat (FG-4592) 1 11 19 Imatinib Mesylate (STI571) 1 12 0 Sunitinib Malate 1 13 34 Vismodegib (GDC-0449) 1 14 64 Paclitaxel 1 15 89 Aprepitant 1 16 94 Decitabine 1 17 -79 Bendamustine HCl 1 18 19 Temozolomide 1 19 -111 Nepafenac 1 20 24 Nintedanib (BIBF 1120) 1 21 -43 Lapatinib (GW-572016) Ditosylate 1 22 88 Temsirolimus (CCI-779, NSC 683864) 1 23 96 Belinostat (PXD101) 1 24 46 Capecitabine 1 25 19 Bicalutamide 1 26 83 Dutasteride 1 27 68 Epirubicin HCl 1 28 -59 Tamoxifen 1 29 30 Rufinamide 1 30 96 Afatinib (BIBW2992) 1 31 -54 Lenalidomide (CC-5013) 1 32 19 Vorinostat (SAHA, MK0683) 1 33 38 Rucaparib (AG-014699,PF-01367338) phosphate1 34 14 Lenvatinib (E7080) 1 35 80 Fulvestrant 1 36 76 Melatonin 1 37 15 Etoposide 1 38 -69 Vincristine sulfate 1 39 61 Posaconazole 1 40 97 Bortezomib (PS-341) 1 41 71 Panobinostat (LBH589) 1 42 41 Entinostat (MS-275) 1 43 26 Cabozantinib (XL184, BMS-907351) 1 44 79 Valproic acid sodium salt (Sodium valproate) 1 45 7 Raltitrexed 1 46 39 Bisoprolol fumarate 1 47 -23 Raloxifene HCl 1 48 97 Agomelatine 1 49 35 Prasugrel 1 50 -24 Bosutinib (SKI-606) 1 51 85 Nilotinib (AMN-107) 1 52 99 Enzastaurin (LY317615) 1 53 -12 Everolimus (RAD001) 1 54 94 Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506) 1 55 24 Thalidomide 1 56 40 Tivozanib (AV-951) 1 57 86 Fludarabine -

Role of Betahistine in the Management of Vertigo

Published online: 2019-01-04 THIEME Review Article 51 Role of Betahistine in the Management of Vertigo Anirban Biswas1 Nilotpal Dutta1 1Vertigo and Deafness Clinic, Kolkata, West Bengal, India Address for correspondence Anirban Biswas, MBBS, DLO, Vertigo and Deafness Clinic, BJ 252, Salt Lake, Kolkata 700091, West Bengal, India (e-mail: [email protected]). Ann Otol Neurotol ISO 2018;1:51–57 Abstract Though betahistine is the most commonly prescribed drug for vertigo, there are a lot of controversies on its efficacy as well as its proclaimed mechanism of action. There are authentic studies that have shown it to be no different from a placebo in Ménière’s disease. It is often promoted as a vestibular stimulant, but scientific evidence suggests that it is a vestibular suppressant. It is also not very clear whether it is an H3-receptor antagonist as most promotional literature shows it to be, or whether it is an inverse agonist of the H3 receptors. Owing to insufficient data on its efficacy in Ménière’s dis- ease, betahistine is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The much-advertised role of betahistine in augmenting histaminergic transmission and thereby inducing arousal, though beneficial is some ways in the restoration of balance after peripheral vestibulopathy, is yet not without systemic problems, and the pros and cons of histaminergic stimulation in the brain need to be assessed more by clinical studies in humans before imbibing it in clinical practice. The effect of increasing blood flow to the cochlea and the vestibular labyrinth and “rebalancing the vestibular nuclei” (as claimed in some literature) and whether they are actually beneficial to the patient with vertigo in the therapeutic doses are very controversial issues. -

The American Journal Of

The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal July 2015 Volume 10 Issue 7 Inside IN THIS ISSUE 2 New Formats and New Opportunities: The Time to Get Involved is “Now”! Rajiv Radhakrishnan, M.B.B.S., M.D. 3 Prevention of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Predicting Response to Trauma Jennifer H. Harris, M.D. 7 Weight Gain in Patients With Schizophrenia: A Recipe For Timely Intervention Ammar El Sara, M.B.Ch.B. 10 Hyperprolactinemia and Antipsychotics: Update for the Training Psychiatrist Stephanie Pope, M.D. 13 A Clinical Case Conference on Spiritual Growth and Healing Elizabeth S. Stevens, D.O. This issue of the Residents’ Journal features a variety of topics. Jennifer H. Har- ris, M.D., discusses prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder, with an overview 15 Priapism: A Rare but Serious of various responses to trauma. Ammar El Sara, M.B.Ch.B., presents a review of Side Effect of Trazodone clinically applicable evidence-based interventions targeting obesity in schizophre- Kamalika Roy, M.D. nia patients. Stephanie Pope, M.D., examines antipsychotic-induced hyperprolac- 17 Classifying Psychopathology: tinemia, including variables affecting prolactin and clinical implications. Elizabeth Mental Kinds and Natural Kinds S. Stevens, D.O., discusses several psychological, social, and spiritual developmen- Reviewed by Aaron J. Hauptman, tal frameworks in a clinical case conference. Kamalika Roy, M.D., presents a case M.D. of priapism as a side effect of trazodone in a middle-aged patient. Lastly, Aaron J. Hauptman, M.D., offers his review of the book Classifying Psychopathology: Mental 18 Residents’ Resources Kinds and Natural Kinds. Editor-in-Chief Associate Editors Editors Emeriti Rajiv Radhakrishnan, M.B.B.S., M.D. -

1. Composition Betahistine 16Mg 2. Dosage Form and Strength Histidiz

1. Composition Betahistine 16mg 2. Dosage form and strength Histidiz tablets are available in pack of 10. The tablet can be divided into two equal halves. 3. Clinical particulars 3.1 Therapeutic indication In treatment of Meniere’s syndrome including Vertigo Tinnitus Nausea Hearing loss 3.2 Posology and method of administration Take one tablet thrice a day or as directed by doctor. 3.3 Contraindication Hypersensitivity Use with caution in asthma, ulcers, GERD and phaeochromocytoma 3.4 Special warnings and precautions for use Following groups of patients should be monitored by a doctor during treatment: Stomach ulcer (peptic ulcer) asthma Nettle rash, skin rash or a cold in the nose caused by an allergy, since these complaints may be exacerbated. Low blood pressure 3.5 Drug interactions Use with caution concurrently with other antihistamines. 3.6 Use in special population Pediatric: Not recommended for use in children and adolescents below age 18 due to lack of data on safety and efficacy. Geriatric: There is limited data in the elderly; Betahistine should be used with caution in this population. Liver impairment: There is no data available for patients with hepatic impairment. Renal failure: There is no data available for patients with renal impairment. Pregnancy and lactation: Consult doctor. 3.7 Effects on ability to drive and use machine Histidiz Tablets are not likely to affect ability to drive or use tools or machinery. However, remember that diseases which are treated with Histidiz tablets (vertigo, tinnitus and hearing loss associated with Meniere’s syndrome) can make patient feel dizzy or be sick, and can affect ability to drive or use machines. -

Jp Xvii the Japanese Pharmacopoeia

JP XVII THE JAPANESE PHARMACOPOEIA SEVENTEENTH EDITION Official from April 1, 2016 English Version THE MINISTRY OF HEALTH, LABOUR AND WELFARE Notice: This English Version of the Japanese Pharmacopoeia is published for the convenience of users unfamiliar with the Japanese language. When and if any discrepancy arises between the Japanese original and its English translation, the former is authentic. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Ministerial Notification No. 64 Pursuant to Paragraph 1, Article 41 of the Law on Securing Quality, Efficacy and Safety of Products including Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices (Law No. 145, 1960), the Japanese Pharmacopoeia (Ministerial Notification No. 65, 2011), which has been established as follows*, shall be applied on April 1, 2016. However, in the case of drugs which are listed in the Pharmacopoeia (hereinafter referred to as ``previ- ous Pharmacopoeia'') [limited to those listed in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia whose standards are changed in accordance with this notification (hereinafter referred to as ``new Pharmacopoeia'')] and have been approved as of April 1, 2016 as prescribed under Paragraph 1, Article 14 of the same law [including drugs the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare specifies (the Ministry of Health and Welfare Ministerial Notification No. 104, 1994) as of March 31, 2016 as those exempted from marketing approval pursuant to Paragraph 1, Article 14 of the Same Law (hereinafter referred to as ``drugs exempted from approval'')], the Name and Standards established in the previous Pharmacopoeia (limited to part of the Name and Standards for the drugs concerned) may be accepted to conform to the Name and Standards established in the new Pharmacopoeia before and on September 30, 2017. -

International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. XCVIII. Histamine Receptors

1521-0081/67/3/601–655$25.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/pr.114.010249 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 67:601–655, July 2015 Copyright © 2015 by The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics ASSOCIATE EDITOR: ELIOT H. OHLSTEIN International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. XCVIII. Histamine Receptors Pertti Panula, Paul L. Chazot, Marlon Cowart, Ralf Gutzmer, Rob Leurs, Wai L. S. Liu, Holger Stark, Robin L. Thurmond, and Helmut L. Haas Department of Anatomy, and Neuroscience Center, University of Helsinki, Finland (P.P.); School of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, University of Durham, United Kingdom (P.L.C.); AbbVie, Inc. North Chicago, Illinois (M.C.); Department of Dermatology and Allergy, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany (R.G.); Department of Medicinal Chemistry, Amsterdam Institute of Molecules, Medicines and Systems, VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands (R.L.); Ziarco Pharma Limited, Canterbury, United Kingdom (W.L.S.L.); Institute of Pharmaceutical and Medical Chemistry (H.S.) and Institute of Neurophysiology, Medical Faculty (H.L.H.), Heinrich-Heine-University Duesseldorf, Germany; and Janssen Research & Development, LLC, San Diego, California (R.L.T.) Abstract ....................................................................................602 Downloaded from I. Introduction and Historical Perspective .....................................................602 II. Histamine H1 Receptor . ..................................................................604 A. Receptor Structure -

Ménière's Disease Treatment: a Patient-Centered Systematic Review

Review Audiology Neurotology Audiol Neurotol 2015;20:153–165 Published online: March 31, 2015 DOI: 10.1159/000375393 Ménière’s Disease Treatment: A Patient-Centered Systematic Review a c b Mariateresa Tassinari Daniele Mandrioli Nadia Gaggioli a, d Paolo Roberti di Sarsina a b Charity Association for Person-Centered Medicine-Moral Entity, Bologna , and Charity Association Ménière’s c Disease Patients Together (AMMI), Bologna , Cesare Maltoni Cancer Research Center, Ramazzini Institute, d Bentivoglio , Bologna , and Observatory and Methods for Health, Department of Sociology and Social Research, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan , Italy Key Words Introduction Ménière’s disease · Idiopathic endolymphatic hydrops · Person-centred healthcare and medicine paradigm Ménière’s disease (idiopathic endolymphatic hydrops) is a disorder of the inner ear that can affect hearing and balance to a varying degree. It is characterized by episodes Abstract of vertigo, low-pitched tinnitus, and hearing loss. The Ménière’s disease is a disorder of the inner ear affecting hear- hearing loss is fluctuating rather than permanent, mean- ing and balance to a varying degree. It is characterized by ing that it comes and goes, alternating between ears for episodes of vertigo, low-pitched tinnitus, and hearing loss. some time, and then it becomes permanent with no re- There is currently no gold standard treatment for Ménière’s turn to normal function. The disease is named after the disease. We conducted a systematic search of the Cochrane French physician Prosper Ménière [Baloh, 2001] who in Database, as a high-quality source of evidence-based thera- two articles published in 1861 [Menière, 1861; Ménière, pies, for reviews on the efficacy of etiological therapy or on 1861] first reported that vertigo was caused by inner ear Ménière’s disease or its symptoms. -

Drug Delivery System for Use in the Treatment Or Diagnosis of Neurological Disorders

(19) TZZ __T (11) EP 2 774 991 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 10.09.2014 Bulletin 2014/37 C12N 15/86 (2006.01) A61K 48/00 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 13001491.3 (22) Date of filing: 22.03.2013 (84) Designated Contracting States: • Manninga, Heiko AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB 37073 Göttingen (DE) GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO •Götzke,Armin PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR 97070 Würzburg (DE) Designated Extension States: • Glassmann, Alexander BA ME 50999 Köln (DE) (30) Priority: 06.03.2013 PCT/EP2013/000656 (74) Representative: von Renesse, Dorothea et al König-Szynka-Tilmann-von Renesse (71) Applicant: Life Science Inkubator Betriebs GmbH Patentanwälte Partnerschaft mbB & Co. KG Postfach 11 09 46 53175 Bonn (DE) 40509 Düsseldorf (DE) (72) Inventors: • Demina, Victoria 53175 Bonn (DE) (54) Drug delivery system for use in the treatment or diagnosis of neurological disorders (57) The invention relates to VLP derived from poly- ment or diagnosis of a neurological disease, in particular oma virus loaded with a drug (cargo) as a drug delivery multiple sclerosis, Parkinsons’s disease or Alzheimer’s system for transporting said drug into the CNS for treat- disease. EP 2 774 991 A1 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 2 774 991 A1 Description FIELD OF THE INVENTION 5 [0001] The invention relates to the use of virus like particles (VLP) of the type of human polyoma virus for use as drug delivery system for the treatment or diagnosis of neurological disorders. -

Prescribing for Older Adults in the Emergency Patient

Prescribing for Older Adults in the Emergency Patient This flipchart is designed to be a quick resource for appropriate medication management of common geriatric conditions. Medications and doses listed are intended for more urgent and acute treatment and not necessarily for long-term use. Examples provided are not an exhaustive list. Created by the Department of Pharmacy, Peace Arch Hospital Originally created February 2012 with funding through a Frank and Yvonne McCracken Foundation Endowment Grant, provided by Peace Arch Hospital Foundation. Reprinted 2014 with funding from: Updated & reprinted Fall 2018 with funding again provided by a Peace Arch Hospital Foundation Frank & Yvonne McCracken Foundation Endowment grant. © - Revised November 2018 © - Revised November 2018 Table of Contents Table of Contents POLYPHARMACY ACUTE ANXITEY DELIRIUM – CAUSES DELIRIUM & AGITATION – TREATMENT DRUG WITHDRAWAL ELECTROLYTE IMBALANCES FALLS INSOMNIA NAUSEA & VOMITING ACUTE PAIN PNEUMONIA URINARY TRACT INFECTION APPENDIX A: ANTICHOLINERGIC SIDE EFFECTS APPENDIX B: EXTRAPYRAMIDAL SYMPTOMS “EPS” APPENDIX C: GERIATRIC RESOURCES © - Revised November 2018 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION – POLYPHARMACY Polypharmacy is the use of more medications than is clinically necessary and is an important consideration in older adults. POLYPHARMACY CAN LEAD TO: • Increased ER visits • Increased risk for adverse drug reactions • Falls • Delirium • Functional decline • Decreased appetite, weight loss • Swallowing difficulties • Increased drug-drug interactions • Changes