Prescribing for Older Adults in the Emergency Patient

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

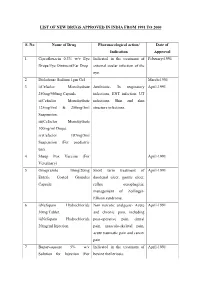

List of New Drugs Approved in India from 1991 to 2000

LIST OF NEW DRUGS APPROVED IN INDIA FROM 1991 TO 2000 S. No Name of Drug Pharmacological action/ Date of Indication Approval 1 Ciprofloxacin 0.3% w/v Eye Indicated in the treatment of February-1991 Drops/Eye Ointment/Ear Drop external ocular infection of the eye. 2 Diclofenac Sodium 1gm Gel March-1991 3 i)Cefaclor Monohydrate Antibiotic- In respiratory April-1991 250mg/500mg Capsule. infections, ENT infection, UT ii)Cefaclor Monohydrate infections, Skin and skin 125mg/5ml & 250mg/5ml structure infections. Suspension. iii)Cefaclor Monohydrate 100mg/ml Drops. iv)Cefaclor 187mg/5ml Suspension (For paediatric use). 4 Sheep Pox Vaccine (For April-1991 Veterinary) 5 Omeprazole 10mg/20mg Short term treatment of April-1991 Enteric Coated Granules duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, Capsule reflux oesophagitis, management of Zollinger- Ellison syndrome. 6 i)Nefopam Hydrochloride Non narcotic analgesic- Acute April-1991 30mg Tablet. and chronic pain, including ii)Nefopam Hydrochloride post-operative pain, dental 20mg/ml Injection. pain, musculo-skeletal pain, acute traumatic pain and cancer pain. 7 Buparvaquone 5% w/v Indicated in the treatment of April-1991 Solution for Injection (For bovine theileriosis. Veterinary) 8 i)Kitotifen Fumerate 1mg Anti asthmatic drug- Indicated May-1991 Tablet in prophylactic treatment of ii)Kitotifen Fumerate Syrup bronchial asthma, symptomatic iii)Ketotifen Fumerate Nasal improvement of allergic Drops conditions including rhinitis and conjunctivitis. 9 i)Pefloxacin Mesylate Antibacterial- In the treatment May-1991 Dihydrate 400mg Film Coated of severe infection in adults Tablet caused by sensitive ii)Pefloxacin Mesylate microorganism (gram -ve Dihydrate 400mg/5ml Injection pathogens and staphylococci). iii)Pefloxacin Mesylate Dihydrate 400mg I.V Bottles of 100ml/200ml 10 Ofloxacin 100mg/50ml & Indicated in RTI, UTI, May-1991 200mg/100ml vial Infusion gynaecological infection, skin/soft lesion infection. -

Anaesthesia and Past Use Of

177 Correspondence were using LSD. It is more popular than other commonly Anaesthesia and past use of used hallucinogens whose quoted incidence of clients are: LSD ketamine 0.1% (super-K/vitamin K.I), psilocybin and psilocin 0.6% (the active alkaloids in the Mexican "magic To the Editor: mushroom"), and 3,4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine We report the case of a 43-yr-old lady who was admitted ~MDMA" 1% (ecstasy). The effects of the concurrent to the Day Surgery Unit for release of her carpal tunnel ingestion of LSD on anaesthesia are well described. 2-4 retinaculum. During the preoperative visit, she reported The long-term effects of the past use of LSD are largely no intercurrent illnesses, drug therapy or allergies. She unknown. We wonder if the hallucinations experienced did say, however, that she was frightened of general anaes- by our patient during anaesthesia were due to her LSD thesia, since she had experienced terrifying dreams during intake many years before. We would be interested to surgery under general anaesthesia on three occasions dur- know if others have had experience anaesthetising patients ing the previous ten years. On further questioning, she who are past users of phencyclidine-derived drugs. admitted that she had used lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) during the late 1960's, the last occasion being 1968 Geoffrey N. Morris MRCGPFRCA when she had experienced characterstic hallucinations. Patrick T. Magee MSe FRCA She had not experienced hallucinations in the ensuing Anaesthetic Department years, except on the surgical occasions mentioned. Royal United Hospital One of the three previous operations had been per- Combe Park formed at our hospital and the anaesthetic record was Bath BA1 3NG checked. -

Schizophrenia Care Guide

August 2015 CCHCS/DHCS Care Guide: Schizophrenia SUMMARY DECISION SUPPORT PATIENT EDUCATION/SELF MANAGEMENT GOALS ALERTS Minimize frequency and severity of psychotic episodes Suicidal ideation or gestures Encourage medication adherence Abnormal movements Manage medication side effects Delusions Monitor as clinically appropriate Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Danger to self or others DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA/EVALUATION (PER DSM V) 1. Rule out delirium or other medical illnesses mimicking schizophrenia (see page 5), medications or drugs of abuse causing psychosis (see page 6), other mental illness causes of psychosis, e.g., Bipolar Mania or Depression, Major Depression, PTSD, borderline personality disorder (see page 4). Ideas in patients (even odd ideas) that we disagree with can be learned and are therefore not necessarily signs of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is a world-wide phenomenon that can occur in cultures with widely differing ideas. 2. Diagnosis is made based on the following: (Criteria A and B must be met) A. Two of the following symptoms/signs must be present over much of at least one month (unless treated), with a significant impact on social or occupational functioning, over at least a 6-month period of time: Delusions, Hallucinations, Disorganized Speech, Negative symptoms (social withdrawal, poverty of thought, etc.), severely disorganized or catatonic behavior. B. At least one of the symptoms/signs should be Delusions, Hallucinations, or Disorganized Speech. TREATMENT OPTIONS MEDICATIONS Informed consent for psychotropic -

Tall Man Lettering List REPORT DECEMBER 2013 1

Tall Man Lettering List REPORT DECEMBER 2013 1 TALL MAN LETTERING LIST REPORT WWW.HQSC.GOVT.NZ Published in December 2013 by the Health Quality & Safety Commission. This document is available on the Health Quality & Safety Commission website, www.hqsc.govt.nz ISBN: 978-0-478-38555-7 (online) Citation: Health Quality & Safety Commission. 2013. Tall Man Lettering List Report. Wellington: Health Quality & Safety Commission. Crown copyright ©. This copyright work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 New Zealand licence. In essence, you are free to copy and distribute the work (including other media and formats), as long as you attribute the work to the Health Quality & Safety Commission. The work must not be adapted and other licence terms must be abided. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/nz/ Copyright enquiries If you are in doubt as to whether a proposed use is covered by this licence, please contact: National Medication Safety Programme Team Health Quality & Safety Commission PO Box 25496 Wellington 6146 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Health Quality & Safety Commission acknowledges the following for their assistance in producing the New Zealand Tall Man lettering list: • The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care for advice and support in allowing its original work to be either reproduced in whole or altered in part for New Zealand as per its copyright1 • The Medication Safety and Quality Program of Clinical Excellence Commission, New South -

Effectiveness of Olanzapine for the Treatment of Breakthrough

Effectiveness of Olanzapine for the Treatment of Breakthrough Chemotherapy Induced Nausea and Vomiting Suthan Chanthawong BPharm*, Suphat Subongkot PharmD*, Aumkhae Sookprasert MD** * Division of Clinical Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand ** Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand Objective: To evaluate safety and efficacy of olanzapine for breakthrough emesis in addition to standard antiemetic regimen in cancer patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Material and Method: A phase II prospective open label clinical trial was conducted in tertiary care based hospital. Forty-six cancer patients diagnosed with solid tumors were enrolled to receive at least one cycle of highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) every two to four weeks. Each patient was provided standard antiemetic consisting of the generic form of ondansetron plus corticosteroids and metoclopramide according to clinical practice guideline. Olanzapine was administered as 5 mg orally every 12 hours for two doses in patients experiencing breakthrough emesis for at least one episode despite standard prevention. The efficacy and tolerability were evaluated every six hours for 24 hours (utilizing Index of Nausea, Vomiting and Retching: INVR tool). Results: Of 46 evaluable patients receiving HEC and additional olanzapine between September 2009 and July 2010, the complete response of breakthrough emesis, retching, and nausea control among patients were 60.9%, 71.7%, and 50.0%, respectively. Adverse events reported were mild and tolerable including dizziness, fatigue, and dyspepsia. Conclusion: Olanzapine is considered to be safe and effective treatment of breakthrough vomiting in cancer patients undergoing highly emetogenic chemotherapy in the present study. Keywords: Olanzapine, Chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting, Breakthrough vomiting, Ondansetron, Metoclopramide, Dexamethasone J Med Assoc Thai 2014; 97 (3): 349-55 Full text. -

Management of Major Depressive Disorder Clinical Practice Guidelines May 2014

Federal Bureau of Prisons Management of Major Depressive Disorder Clinical Practice Guidelines May 2014 Table of Contents 1. Purpose ............................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Natural History ................................................................................................................................. 2 Special Considerations ...................................................................................................................... 2 3. Screening ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Screening Questions .......................................................................................................................... 3 Further Screening Methods................................................................................................................ 4 4. Diagnosis ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Depression: Three Levels of Severity ............................................................................................... 4 Clinical Interview and Documentation of Risk Assessment............................................................... -

Package Leaflet: Information for the User Hydroxyzine Bluefish 25 Mg

Package leaflet: Information for the user Hydroxyzine Bluefish 25 mg film-coated tablets hydroxyzine hydrochloride Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start using this medicine because it contains important information for you. - Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. - If you have any further questions, ask your doctor or pharmacist. - This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same as yours. - If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet 1. What Hydroxyzine Bluefish is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you use Hydroxyzine Bluefish 3. How to use Hydroxyzine Bluefish 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Hydroxyzine Bluefish 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Hydroxyzine Bluefish is and what it is used for Hydroxyzine Bluefish blocks histamine, a substance found in body tissues. It is effective against anxiety, itching and urticaria. Hydroxyzine Bluefish is used to treat anxiety in adults itching (pruritus) associated with hives (urticaria) in adults adolescents and children of 5 years and above 2. What you need to know before you take Hydroxyzine Bluefish Do not take Hydroxyzine Bluefish - if you are allergic to hydroxyzine hydrochloride or any of the other ingredients of this medicine (listed in section 6) - if you are allergic (hypersensitive) to cetirizine, aminophylline, ethylenediamine or piperazine derivatives (closely related active substances of other medicines). -

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Cr

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Crizotinib (PF-02341066) 1 4 55 Docetaxel 1 5 98 Anastrozole 1 6 25 Cladribine 1 7 23 Methotrexate 1 8 -187 Letrozole 1 9 65 Entecavir Hydrate 1 10 48 Roxadustat (FG-4592) 1 11 19 Imatinib Mesylate (STI571) 1 12 0 Sunitinib Malate 1 13 34 Vismodegib (GDC-0449) 1 14 64 Paclitaxel 1 15 89 Aprepitant 1 16 94 Decitabine 1 17 -79 Bendamustine HCl 1 18 19 Temozolomide 1 19 -111 Nepafenac 1 20 24 Nintedanib (BIBF 1120) 1 21 -43 Lapatinib (GW-572016) Ditosylate 1 22 88 Temsirolimus (CCI-779, NSC 683864) 1 23 96 Belinostat (PXD101) 1 24 46 Capecitabine 1 25 19 Bicalutamide 1 26 83 Dutasteride 1 27 68 Epirubicin HCl 1 28 -59 Tamoxifen 1 29 30 Rufinamide 1 30 96 Afatinib (BIBW2992) 1 31 -54 Lenalidomide (CC-5013) 1 32 19 Vorinostat (SAHA, MK0683) 1 33 38 Rucaparib (AG-014699,PF-01367338) phosphate1 34 14 Lenvatinib (E7080) 1 35 80 Fulvestrant 1 36 76 Melatonin 1 37 15 Etoposide 1 38 -69 Vincristine sulfate 1 39 61 Posaconazole 1 40 97 Bortezomib (PS-341) 1 41 71 Panobinostat (LBH589) 1 42 41 Entinostat (MS-275) 1 43 26 Cabozantinib (XL184, BMS-907351) 1 44 79 Valproic acid sodium salt (Sodium valproate) 1 45 7 Raltitrexed 1 46 39 Bisoprolol fumarate 1 47 -23 Raloxifene HCl 1 48 97 Agomelatine 1 49 35 Prasugrel 1 50 -24 Bosutinib (SKI-606) 1 51 85 Nilotinib (AMN-107) 1 52 99 Enzastaurin (LY317615) 1 53 -12 Everolimus (RAD001) 1 54 94 Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506) 1 55 24 Thalidomide 1 56 40 Tivozanib (AV-951) 1 57 86 Fludarabine -

The Vomiting Center and the Chemoreceptor Trigger Zone

Pharmacologic Control of Vomiting Todd R. Tams, DVM, Dipl. ACVIM VCA West Los Angeles Animal Hospital Pharmacologic Control of Acute Vomiting Initial nonspecific management of vomiting includes NPO (in minor cases a 6-12 hour period of nothing per os may be all that is required), fluid support, and antiemetics. Initial feeding includes small portions of a low fat, single source protein diet starting 6-12 hours after vomiting has ceased. Drugs used to control vomiting will be discussed here. The most effective antiemetics are those that act at both the vomiting center and the chemoreceptor trigger zone. Vomiting is a protective reflex and when it occurs only occasionally treatment is not generally required. However, patients that continue to vomit should be given antiemetics to help reduce fluid loss, pain and discomfort. For many years I strongly favored chlorpromazine (Thorazine), a phenothiazine drug, as the first choice for pharmacologic control of vomiting in most cases. The HT-3 receptor antagonists ondansetron (Zofran) and dolasetron (Anzemet) have also been highly effective antiemetic drugs for a variety of causes of vomiting. Metoclopramide (Reglan) is a reasonably good central antiemetic drug for dogs but not for cats. Maropitant (Cerenia) is a superior broad spectrum antiemetic drug and is now recognized as an excellent first choice for control of vomiting in dogs. Studies and clinical experience have now also shown maropitant to be an effective and safe antiemetic drug for cats. While it is labeled only for dogs, clinical experience has shown it is safe to use the drug in cats as well. Maropitant is also the first choice for prevention of motion sickness vomiting in both dogs and cats. -

Role of Betahistine in the Management of Vertigo

Published online: 2019-01-04 THIEME Review Article 51 Role of Betahistine in the Management of Vertigo Anirban Biswas1 Nilotpal Dutta1 1Vertigo and Deafness Clinic, Kolkata, West Bengal, India Address for correspondence Anirban Biswas, MBBS, DLO, Vertigo and Deafness Clinic, BJ 252, Salt Lake, Kolkata 700091, West Bengal, India (e-mail: [email protected]). Ann Otol Neurotol ISO 2018;1:51–57 Abstract Though betahistine is the most commonly prescribed drug for vertigo, there are a lot of controversies on its efficacy as well as its proclaimed mechanism of action. There are authentic studies that have shown it to be no different from a placebo in Ménière’s disease. It is often promoted as a vestibular stimulant, but scientific evidence suggests that it is a vestibular suppressant. It is also not very clear whether it is an H3-receptor antagonist as most promotional literature shows it to be, or whether it is an inverse agonist of the H3 receptors. Owing to insufficient data on its efficacy in Ménière’s dis- ease, betahistine is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The much-advertised role of betahistine in augmenting histaminergic transmission and thereby inducing arousal, though beneficial is some ways in the restoration of balance after peripheral vestibulopathy, is yet not without systemic problems, and the pros and cons of histaminergic stimulation in the brain need to be assessed more by clinical studies in humans before imbibing it in clinical practice. The effect of increasing blood flow to the cochlea and the vestibular labyrinth and “rebalancing the vestibular nuclei” (as claimed in some literature) and whether they are actually beneficial to the patient with vertigo in the therapeutic doses are very controversial issues. -

The American Journal Of

The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal July 2015 Volume 10 Issue 7 Inside IN THIS ISSUE 2 New Formats and New Opportunities: The Time to Get Involved is “Now”! Rajiv Radhakrishnan, M.B.B.S., M.D. 3 Prevention of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Predicting Response to Trauma Jennifer H. Harris, M.D. 7 Weight Gain in Patients With Schizophrenia: A Recipe For Timely Intervention Ammar El Sara, M.B.Ch.B. 10 Hyperprolactinemia and Antipsychotics: Update for the Training Psychiatrist Stephanie Pope, M.D. 13 A Clinical Case Conference on Spiritual Growth and Healing Elizabeth S. Stevens, D.O. This issue of the Residents’ Journal features a variety of topics. Jennifer H. Har- ris, M.D., discusses prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder, with an overview 15 Priapism: A Rare but Serious of various responses to trauma. Ammar El Sara, M.B.Ch.B., presents a review of Side Effect of Trazodone clinically applicable evidence-based interventions targeting obesity in schizophre- Kamalika Roy, M.D. nia patients. Stephanie Pope, M.D., examines antipsychotic-induced hyperprolac- 17 Classifying Psychopathology: tinemia, including variables affecting prolactin and clinical implications. Elizabeth Mental Kinds and Natural Kinds S. Stevens, D.O., discusses several psychological, social, and spiritual developmen- Reviewed by Aaron J. Hauptman, tal frameworks in a clinical case conference. Kamalika Roy, M.D., presents a case M.D. of priapism as a side effect of trazodone in a middle-aged patient. Lastly, Aaron J. Hauptman, M.D., offers his review of the book Classifying Psychopathology: Mental 18 Residents’ Resources Kinds and Natural Kinds. Editor-in-Chief Associate Editors Editors Emeriti Rajiv Radhakrishnan, M.B.B.S., M.D. -

PRESCRIBED DRUGS and NEUROLOGICAL COMPLICATIONS K a Grosset, D G Grosset Iii2

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.2004.045757 on 16 August 2004. Downloaded from PRESCRIBED DRUGS AND NEUROLOGICAL COMPLICATIONS K A Grosset, D G Grosset iii2 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75(Suppl III):iii2–iii8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.045757 treatment history is a fundamental part of the healthcare consultation. Current drugs (prescribed, over the counter, herbal remedies, drugs of misuse) and how they are taken A(frequency, timing, missed and extra doses), drugs tried previously and reason for discontinuation, treatment response, adverse effects, allergies, and intolerances should be taken into account. Recent immunisations may also be of importance. This article examines the particular relevance of medication in patients presenting with neurological symptoms. Drugs and their interactions may contribute in part or fully to the neurological syndrome, and treatment response may assist diagnostically or in future management plans. Knowledge of medicine taking behaviour may clarify clinical presentations such as analgesic overuse causing chronic daily headache, or severe dyskinesia resulting from obsessive use of dopamine replacement treatment. In most cases, iatrogenic symptoms are best managed by withdrawal of the offending drug. Indirect mechanisms whereby drugs could cause neurological problems are beyond the scope of the current article—for example, drugs which raise blood pressure or which worsen glycaemic control and consequently increase the risk of cerebrovascular disease, or immunosupressants