The American Journal Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

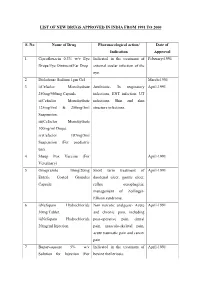

List of New Drugs Approved in India from 1991 to 2000

LIST OF NEW DRUGS APPROVED IN INDIA FROM 1991 TO 2000 S. No Name of Drug Pharmacological action/ Date of Indication Approval 1 Ciprofloxacin 0.3% w/v Eye Indicated in the treatment of February-1991 Drops/Eye Ointment/Ear Drop external ocular infection of the eye. 2 Diclofenac Sodium 1gm Gel March-1991 3 i)Cefaclor Monohydrate Antibiotic- In respiratory April-1991 250mg/500mg Capsule. infections, ENT infection, UT ii)Cefaclor Monohydrate infections, Skin and skin 125mg/5ml & 250mg/5ml structure infections. Suspension. iii)Cefaclor Monohydrate 100mg/ml Drops. iv)Cefaclor 187mg/5ml Suspension (For paediatric use). 4 Sheep Pox Vaccine (For April-1991 Veterinary) 5 Omeprazole 10mg/20mg Short term treatment of April-1991 Enteric Coated Granules duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, Capsule reflux oesophagitis, management of Zollinger- Ellison syndrome. 6 i)Nefopam Hydrochloride Non narcotic analgesic- Acute April-1991 30mg Tablet. and chronic pain, including ii)Nefopam Hydrochloride post-operative pain, dental 20mg/ml Injection. pain, musculo-skeletal pain, acute traumatic pain and cancer pain. 7 Buparvaquone 5% w/v Indicated in the treatment of April-1991 Solution for Injection (For bovine theileriosis. Veterinary) 8 i)Kitotifen Fumerate 1mg Anti asthmatic drug- Indicated May-1991 Tablet in prophylactic treatment of ii)Kitotifen Fumerate Syrup bronchial asthma, symptomatic iii)Ketotifen Fumerate Nasal improvement of allergic Drops conditions including rhinitis and conjunctivitis. 9 i)Pefloxacin Mesylate Antibacterial- In the treatment May-1991 Dihydrate 400mg Film Coated of severe infection in adults Tablet caused by sensitive ii)Pefloxacin Mesylate microorganism (gram -ve Dihydrate 400mg/5ml Injection pathogens and staphylococci). iii)Pefloxacin Mesylate Dihydrate 400mg I.V Bottles of 100ml/200ml 10 Ofloxacin 100mg/50ml & Indicated in RTI, UTI, May-1991 200mg/100ml vial Infusion gynaecological infection, skin/soft lesion infection. -

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults Strength of Organ System/ Recommendat Quality of Recomm Therapeutic Category/Drug(s) Rationale ion Evidence endation References Anticholinergics (excludes TCAs) First-generation antihistamines Highly anticholinergic; Avoid Hydroxyzin Strong Agostini 2001 (as single agent or as part of clearance reduced with e and Boustani 2007 combination products) advanced age, and promethazi Guaiana 2010 Brompheniramine tolerance develops ne: high; Han 2001 Carbinoxamine when used as hypnotic; All others: Rudolph 2008 Chlorpheniramine increased risk of moderate Clemastine confusion, dry mouth, Cyproheptadine constipation, and other Dexbrompheniramine anticholinergic Dexchlorpheniramine effects/toxicity. Diphenhydramine (oral) Doxylamine Use of diphenhydramine in Hydroxyzine special situations such Promethazine as acute treatment of Triprolidine severe allergic reaction may be appropriate. Antiparkinson agents Not recommended for Avoid Moderate Strong Rudolph 2008 Benztropine (oral) prevention of Trihexyphenidyl extrapyramidal symptoms with antipsychotics; more effective agents available for treatment of Parkinson disease. Antispasmodics Highly anticholinergic, Avoid Moderate Strong Lechevallier- Belladonna alkaloids uncertain except in Michel 2005 Clidinium-chlordiazepoxide effectiveness. short-term Rudolph 2008 Dicyclomine palliative Hyoscyamine care to Propantheline decrease Scopolamine oral secretions. Antithrombotics Dipyridamole, oral short-acting* May -

Appendix A: Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions (Pips) for Older People (Modified from ‘STOPP/START 2’ O’Mahony Et Al 2014)

Appendix A: Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions (PIPs) for older people (modified from ‘STOPP/START 2’ O’Mahony et al 2014) Consider holding (or deprescribing - consult with patient): 1. Any drug prescribed without an evidence-based clinical indication 2. Any drug prescribed beyond the recommended duration, where well-defined 3. Any duplicate drug class (optimise monotherapy) Avoid hazardous combinations e.g.: 1. The Triple Whammy: NSAID + ACE/ARB + diuretic in all ≥ 65 year olds (NHS Scotland 2015) 2. Sick Day Rules drugs: Metformin or ACEi/ARB or a diuretic or NSAID in ≥ 65 year olds presenting with dehydration and/or acute kidney injury (AKI) (NHS Scotland 2015) 3. Anticholinergic Burden (ACB): Any additional medicine with anticholinergic properties when already on an Anticholinergic/antimuscarinic (listed overleaf) in > 65 year olds (risk of falls, increased anticholinergic toxicity: confusion, agitation, acute glaucoma, urinary retention, constipation). The following are known to contribute to the ACB: Amantadine Antidepressants, tricyclic: Amitriptyline, Clomipramine, Dosulepin, Doxepin, Imipramine, Nortriptyline, Trimipramine and SSRIs: Fluoxetine, Paroxetine Antihistamines, first generation (sedating): Clemastine, Chlorphenamine, Cyproheptadine, Diphenhydramine/-hydrinate, Hydroxyzine, Promethazine; also Cetirizine, Loratidine Antipsychotics: especially Clozapine, Fluphenazine, Haloperidol, Olanzepine, and phenothiazines e.g. Prochlorperazine, Trifluoperazine Baclofen Carbamazepine Disopyramide Loperamide Oxcarbazepine Pethidine -

Commonly Prescribed Psychotropic Medications

COMMONLY PRESCRIBED PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATIONS NAME Generic (Trade) DOSAGE KEY CLINICAL INFORMATION Antidepressant Medications* Start: IR-100 mg bid X 4d then ↑ to 100 mg tid; SR-150 mg qam X 4d then ↑ to 150 mg Contraindicated in seizure disorder because it decreases seizure threshold; stimulating; not good for treating anxiety disorders; second Bupropion (Wellbutrin) bid; XL-150 mg qam X 4d, then ↑ to 300 mg qam. Range: 300-450 mg/d. line TX for ADHD; abuse potential. ¢ (IR/SR), $ (XL) Citalopram (Celexa) Start: 10-20 mg qday,↑10-20 mg q4-7d to 30-40 mg qday. Range: 20-60 mg/d. Best tolerated of SSRIs; very few and limited CYP 450 interactions; good choice for anxious pt. ¢ Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Start: 30 mg qday X 1 wk, then ↑ to 60 mg qday. Range: 60-120 mg/d. More GI side effects than SSRIs; tx neuropathic pain; need to monitor BP; 2nd line tx for ADHD. $ Escitalopram (Lexapro) Start: 5 mg qday X 4-7d then ↑ to 10 mg qday. Range 10-30 mg/d (3X potent vs. Celexa). Best tolerated of SSRIs, very few and limited CYP 450 interactions. Good choice for anxious pt. $ Fluoxetine (Prozac) Start: 10 mg qam X 4-7d then ↑ to 20 mg qday. Range: 20-60 mg/d. More activating than other SSRIs; long half-life reduces withdrawal (t ½ = 4-6 d). ¢ Mirtazapine (Remeron) Start: 15 mg qhs. X 4-7d then ↑ to 30 mg qhs. Range: 30-60 mg/qhs. Sedating and appetite promoting; Neutropenia risk (1 in 1000) so avoid in immunosupressed patients. -

Clomipramine | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

PATIENT & CAREGIVER EDUCATION Clomipramine This information from Lexicomp® explains what you need to know about this medication, including what it’s used for, how to take it, its side effects, and when to call your healthcare provider. Brand Names: US Anafranil Brand Names: Canada Anafranil; MED ClomiPRAMINE; TARO-Clomipramine Warning Drugs like this one have raised the chance of suicidal thoughts or actions in children and young adults. The risk may be greater in people who have had these thoughts or actions in the past. All people who take this drug need to be watched closely. Call the doctor right away if signs like low mood (depression), nervousness, restlessness, grouchiness, panic attacks, or changes in mood or actions are new or worse. Call the doctor right away if any thoughts or actions of suicide occur. This drug is not approved for use in all children. Talk with the doctor to be sure that this drug is right for your child. What is this drug used for? It is used to treat obsessive-compulsive problems. It may be given to you for other reasons. Talk with the doctor. Clomipramine 1/8 What do I need to tell my doctor BEFORE I take this drug? If you have an allergy to clomipramine or any other part of this drug. If you are allergic to this drug; any part of this drug; or any other drugs, foods, or substances. Tell your doctor about the allergy and what signs you had. If you have had a recent heart attack. If you are taking any of these drugs: Linezolid or methylene blue. -

Tall Man Lettering List REPORT DECEMBER 2013 1

Tall Man Lettering List REPORT DECEMBER 2013 1 TALL MAN LETTERING LIST REPORT WWW.HQSC.GOVT.NZ Published in December 2013 by the Health Quality & Safety Commission. This document is available on the Health Quality & Safety Commission website, www.hqsc.govt.nz ISBN: 978-0-478-38555-7 (online) Citation: Health Quality & Safety Commission. 2013. Tall Man Lettering List Report. Wellington: Health Quality & Safety Commission. Crown copyright ©. This copyright work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 New Zealand licence. In essence, you are free to copy and distribute the work (including other media and formats), as long as you attribute the work to the Health Quality & Safety Commission. The work must not be adapted and other licence terms must be abided. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/nz/ Copyright enquiries If you are in doubt as to whether a proposed use is covered by this licence, please contact: National Medication Safety Programme Team Health Quality & Safety Commission PO Box 25496 Wellington 6146 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Health Quality & Safety Commission acknowledges the following for their assistance in producing the New Zealand Tall Man lettering list: • The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care for advice and support in allowing its original work to be either reproduced in whole or altered in part for New Zealand as per its copyright1 • The Medication Safety and Quality Program of Clinical Excellence Commission, New South -

Prazosin: Preliminary Report and Comparative Studies with Other

298 BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL 1 1 MAY 1974 Prazosin: Preliminary Report and Comparative Studies with Other Antihypertensive Agents Br Med J: first published as 10.1136/bmj.2.5914.298 on 11 May 1974. Downloaded from GORDON S. STOKES, MICHAEL A. WEBER British Medical Journal, 1974, 2, 298-300 bilirubin. One patient had minimal grade 3 hypertensive ocu- lar fundus changes, 10 had grade 1 or 2 changes, and four had normal fundi. Serum crea-tinine concentration was normal in Summary every patient. A diagnosis of uncomplicated essential hypertension was In a group of 14 hypertensive patients a 10-week course made in 12 patients. In two other patients pyelographic of treatment with prazosin 3-7 5 mg/day produced a signifi- evidence of analgesic nephropathy was found. The remaining cant reduction in mean blood pressure without serious side patient had essential hypertension and stable angina pectoris. effects. The fall in diastolic pressure exceeded the response After at least two baseline blood pressure readings, taken mm more to a placebo by 10 Hg or in 9 patients. The average when patients were recumbent and standing, treatment was decrease in diastolic pressure was similar to that produced started with prazosin, 1-mg capsules by mouth, three times or by methyldopa 750 mg/day propranolol 120-160 mg/day daily. Thereafter the patient visited the clinic at intervals of was but the fall in systolic pressure comparatively smaller, one to three weeks. At each visit blood pressure was meas- that the consistent with reported experimental work showing ured to the nearest 5 mm Hg with an Accoson sphygmomo- drug causes vasodilatation. -

Package Leaflet: Information for the User Hydroxyzine Bluefish 25 Mg

Package leaflet: Information for the user Hydroxyzine Bluefish 25 mg film-coated tablets hydroxyzine hydrochloride Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start using this medicine because it contains important information for you. - Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. - If you have any further questions, ask your doctor or pharmacist. - This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same as yours. - If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet 1. What Hydroxyzine Bluefish is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you use Hydroxyzine Bluefish 3. How to use Hydroxyzine Bluefish 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Hydroxyzine Bluefish 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Hydroxyzine Bluefish is and what it is used for Hydroxyzine Bluefish blocks histamine, a substance found in body tissues. It is effective against anxiety, itching and urticaria. Hydroxyzine Bluefish is used to treat anxiety in adults itching (pruritus) associated with hives (urticaria) in adults adolescents and children of 5 years and above 2. What you need to know before you take Hydroxyzine Bluefish Do not take Hydroxyzine Bluefish - if you are allergic to hydroxyzine hydrochloride or any of the other ingredients of this medicine (listed in section 6) - if you are allergic (hypersensitive) to cetirizine, aminophylline, ethylenediamine or piperazine derivatives (closely related active substances of other medicines). -

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Cr

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Crizotinib (PF-02341066) 1 4 55 Docetaxel 1 5 98 Anastrozole 1 6 25 Cladribine 1 7 23 Methotrexate 1 8 -187 Letrozole 1 9 65 Entecavir Hydrate 1 10 48 Roxadustat (FG-4592) 1 11 19 Imatinib Mesylate (STI571) 1 12 0 Sunitinib Malate 1 13 34 Vismodegib (GDC-0449) 1 14 64 Paclitaxel 1 15 89 Aprepitant 1 16 94 Decitabine 1 17 -79 Bendamustine HCl 1 18 19 Temozolomide 1 19 -111 Nepafenac 1 20 24 Nintedanib (BIBF 1120) 1 21 -43 Lapatinib (GW-572016) Ditosylate 1 22 88 Temsirolimus (CCI-779, NSC 683864) 1 23 96 Belinostat (PXD101) 1 24 46 Capecitabine 1 25 19 Bicalutamide 1 26 83 Dutasteride 1 27 68 Epirubicin HCl 1 28 -59 Tamoxifen 1 29 30 Rufinamide 1 30 96 Afatinib (BIBW2992) 1 31 -54 Lenalidomide (CC-5013) 1 32 19 Vorinostat (SAHA, MK0683) 1 33 38 Rucaparib (AG-014699,PF-01367338) phosphate1 34 14 Lenvatinib (E7080) 1 35 80 Fulvestrant 1 36 76 Melatonin 1 37 15 Etoposide 1 38 -69 Vincristine sulfate 1 39 61 Posaconazole 1 40 97 Bortezomib (PS-341) 1 41 71 Panobinostat (LBH589) 1 42 41 Entinostat (MS-275) 1 43 26 Cabozantinib (XL184, BMS-907351) 1 44 79 Valproic acid sodium salt (Sodium valproate) 1 45 7 Raltitrexed 1 46 39 Bisoprolol fumarate 1 47 -23 Raloxifene HCl 1 48 97 Agomelatine 1 49 35 Prasugrel 1 50 -24 Bosutinib (SKI-606) 1 51 85 Nilotinib (AMN-107) 1 52 99 Enzastaurin (LY317615) 1 53 -12 Everolimus (RAD001) 1 54 94 Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506) 1 55 24 Thalidomide 1 56 40 Tivozanib (AV-951) 1 57 86 Fludarabine -

Antidepressants the Old and the New

Antidepressants The Old and The New October, 1998 iii In 1958 researchers discovered that imipramine had antidepressant 1 activity. Since then, a number of antidepressants have been HIGHLIGHTS developed with a variety of pharmacological mechanisms and side effect profiles. All antidepressants show similar efficacy in the treatment of depression when used in adequate dosages. Choosing the most PHARMACOLOGY & CLASSIFICATION appropriate agent depends on specific patient variables, The mechanism of action for antidepressants is not entirely clear; concurrent diseases, concurrent drugs, and cost. however they are known to interfere with neurotransmitters. Non-TCA antidepressants such as the SSRIs have become Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) block the reuptake of both first line agents in the treatment of depression due to their norepinephrine (NE) and serotonin (5HT). The relative ratio of relative safety and tolerability. Each has its own advantages and their effect on NE versus 5HT varies. The potentiation of NE and disadvantages for consideration in individualizing therapy. 5HT results in changes in the neuroreceptors and is thought to be TCAs may be preferred in patients who do not respond to or the primary mechanism responsible for the antidepressant effect. tolerate other antidepressants, have chronic pain or migraine, or In addition to the effects on NE and 5HT, TCAs also block for whom drug cost is a significant factor. muscarinic, alpha1 adrenergic, and histaminic receptors. The extent of these effects vary with each agent resulting in differing Secondary amine TCAs (desipramine and nortriptyline) have side effect profiles. fewer side effects than tertiary amine TCAs. Maintenance therapy at full therapeutic dosages should be Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) block the 2 considered for patients at high risk for recurrence. -

IHS National Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee National

IHS National Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee National Core Formulary; Last Updated: 09/23/2021 **Note: Medications in GREY indicate removed items.** Generic Medication Name Pharmacological Category (up-to-date) Formulary Brief (if Notes / Similar NCF Active? available) Miscellaneous Medications Acetaminophen Analgesic, Miscellaneous Yes Albuterol nebulized solution Beta2 Agonist Yes Albuterol, metered dose inhaler Beta2 Agonist NPTC Meeting Update *Any product* Yes (MDI) (Nov 2017) Alendronate Bisphosphonate Derivative Osteoporosis (2016) Yes Allopurinol Antigout Agent; Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitor Gout (2016) Yes Alogliptin Antidiabetic Agent, Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 (DPP-4) Inhibitor DPP-IV Inhibitors (2019) Yes Anastrozole Antineoplastic Agent, Aromatase Inhibitor Yes Aspirin Antiplatelet Agent; Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug; Salicylate Yes Azithromycin Antibiotic, Macrolide STIs - PART 1 (2021) Yes Calcium Electrolyte supplement *Any formulation* Yes Carbidopa-Levodopa (immediate Anti-Parkinson Agent; Decarboxylase Inhibitor-Dopamine Precursor Parkinson's Disease Yes release) (2019) Clindamycin, topical ===REMOVED from NCF=== (See Benzoyl Peroxide AND Removed January No Clindamycin, topical combination) 2020 Corticosteroid, intranasal Intranasal Corticosteroid *Any product* Yes Cyanocobalamin (Vitamin B12), Vitamin, Water Soluble Hematologic Supplements Yes oral (2016) Printed on 09/25/2021 Page 1 of 18 National Core Formulary; Last Updated: 09/23/2021 Generic Medication Name Pharmacological Category (up-to-date) Formulary Brief -

Role of Betahistine in the Management of Vertigo

Published online: 2019-01-04 THIEME Review Article 51 Role of Betahistine in the Management of Vertigo Anirban Biswas1 Nilotpal Dutta1 1Vertigo and Deafness Clinic, Kolkata, West Bengal, India Address for correspondence Anirban Biswas, MBBS, DLO, Vertigo and Deafness Clinic, BJ 252, Salt Lake, Kolkata 700091, West Bengal, India (e-mail: [email protected]). Ann Otol Neurotol ISO 2018;1:51–57 Abstract Though betahistine is the most commonly prescribed drug for vertigo, there are a lot of controversies on its efficacy as well as its proclaimed mechanism of action. There are authentic studies that have shown it to be no different from a placebo in Ménière’s disease. It is often promoted as a vestibular stimulant, but scientific evidence suggests that it is a vestibular suppressant. It is also not very clear whether it is an H3-receptor antagonist as most promotional literature shows it to be, or whether it is an inverse agonist of the H3 receptors. Owing to insufficient data on its efficacy in Ménière’s dis- ease, betahistine is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The much-advertised role of betahistine in augmenting histaminergic transmission and thereby inducing arousal, though beneficial is some ways in the restoration of balance after peripheral vestibulopathy, is yet not without systemic problems, and the pros and cons of histaminergic stimulation in the brain need to be assessed more by clinical studies in humans before imbibing it in clinical practice. The effect of increasing blood flow to the cochlea and the vestibular labyrinth and “rebalancing the vestibular nuclei” (as claimed in some literature) and whether they are actually beneficial to the patient with vertigo in the therapeutic doses are very controversial issues.