Meniere's Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

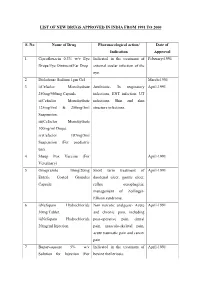

List of New Drugs Approved in India from 1991 to 2000

LIST OF NEW DRUGS APPROVED IN INDIA FROM 1991 TO 2000 S. No Name of Drug Pharmacological action/ Date of Indication Approval 1 Ciprofloxacin 0.3% w/v Eye Indicated in the treatment of February-1991 Drops/Eye Ointment/Ear Drop external ocular infection of the eye. 2 Diclofenac Sodium 1gm Gel March-1991 3 i)Cefaclor Monohydrate Antibiotic- In respiratory April-1991 250mg/500mg Capsule. infections, ENT infection, UT ii)Cefaclor Monohydrate infections, Skin and skin 125mg/5ml & 250mg/5ml structure infections. Suspension. iii)Cefaclor Monohydrate 100mg/ml Drops. iv)Cefaclor 187mg/5ml Suspension (For paediatric use). 4 Sheep Pox Vaccine (For April-1991 Veterinary) 5 Omeprazole 10mg/20mg Short term treatment of April-1991 Enteric Coated Granules duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, Capsule reflux oesophagitis, management of Zollinger- Ellison syndrome. 6 i)Nefopam Hydrochloride Non narcotic analgesic- Acute April-1991 30mg Tablet. and chronic pain, including ii)Nefopam Hydrochloride post-operative pain, dental 20mg/ml Injection. pain, musculo-skeletal pain, acute traumatic pain and cancer pain. 7 Buparvaquone 5% w/v Indicated in the treatment of April-1991 Solution for Injection (For bovine theileriosis. Veterinary) 8 i)Kitotifen Fumerate 1mg Anti asthmatic drug- Indicated May-1991 Tablet in prophylactic treatment of ii)Kitotifen Fumerate Syrup bronchial asthma, symptomatic iii)Ketotifen Fumerate Nasal improvement of allergic Drops conditions including rhinitis and conjunctivitis. 9 i)Pefloxacin Mesylate Antibacterial- In the treatment May-1991 Dihydrate 400mg Film Coated of severe infection in adults Tablet caused by sensitive ii)Pefloxacin Mesylate microorganism (gram -ve Dihydrate 400mg/5ml Injection pathogens and staphylococci). iii)Pefloxacin Mesylate Dihydrate 400mg I.V Bottles of 100ml/200ml 10 Ofloxacin 100mg/50ml & Indicated in RTI, UTI, May-1991 200mg/100ml vial Infusion gynaecological infection, skin/soft lesion infection. -

HEARING LOSS, DEAFNESS Ear32 (1)

HEARING LOSS, DEAFNESS Ear32 (1) Hearing Loss, Deafness Last updated: May 11, 2019 CLASSIFICATION, DIAGNOSIS ................................................................................................................. 1 METHODS OF COMMUNICATION FOR DEAF ............................................................................................ 2 MANAGEMENT ......................................................................................................................................... 2 HEARING AIDS (S. AMPLIFICATION) ....................................................................................................... 2 COCHLEAR IMPLANTS ............................................................................................................................ 2 AUDITORY BRAINSTEM IMPLANTS .......................................................................................................... 4 PREVENTION .......................................................................................................................................... 4 PEDIATRIC HEARING DEFICITS ............................................................................................................... 4 ETIOLOGY .............................................................................................................................................. 4 DIAGNOSIS ............................................................................................................................................. 6 TREATMENT .......................................................................................................................................... -

Pediatric Sensorineural Hearing Loss, Part 2: Syndromic And

Published May 19, 2011 as 10.3174/ajnr.A2499 Pediatric Sensorineural Hearing Loss, Part 2: REVIEW ARTICLE Syndromic and Acquired Causes B.Y. Huang SUMMARY: This article is the second in a 2-part series reviewing neuroimaging in childhood SNHL. C. Zdanski Previously, we discussed the clinical work-up of children with hearing impairment, the classification of inner ear malformations, and congenital nonsyndromic causes of hearing loss. Here, we review and M. Castillo illustrate the most common syndromic hereditary and acquired causes of childhood SNHL, with an emphasis on entities that demonstrate inner ear abnormalities on cross-sectional imaging. Syndromes discussed include BOR syndrome, CHARGE syndrome, Pendred syndrome, Waardenburg syndrome, and X-linked hearing loss with stapes gusher. We conclude the article with a review of acquired causes of childhood SNHL, including infections, trauma, and neoplasms. ABBREVIATIONS: BOR ϭ branchio-oto-renal; CISS ϭ constructive interference in steady state; IAC ϭ internal auditory canal; NF-2 ϭ neurofibromatosis type II; SCC ϭ semicircular canal; SNHL ϭ sensorineural hearing loss; T1WI ϭ T1-weighted image; T2 WI ϭ T2-weighted image he estimated prevalence of SNHL in patients younger than Table 1: Selected hereditary syndromes commonly associated with 1 T18 years of age is 6 per 1000, making it one of the leading SNHL causes of childhood disability and a common reason for oto- Inner Ear Malformations on Inner Ear Malformations laryngology referrals. Cross-sectional imaging is now rou- Imaging Not Common on Imaging tinely performed in these patients because it provides impor- Alagille syndrome Alport syndrome tant information about potential etiologies for hearing loss, Branchio-oto-renal syndrome Biotinidase deficiency defines the anatomy of the temporal bone and the central au- CHARGE syndrome Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome ditory pathway, and identifies additional intracranial abnor- Klippel-Feil syndrome Norrie syndrome malities that may require further work-up. -

Tall Man Lettering List REPORT DECEMBER 2013 1

Tall Man Lettering List REPORT DECEMBER 2013 1 TALL MAN LETTERING LIST REPORT WWW.HQSC.GOVT.NZ Published in December 2013 by the Health Quality & Safety Commission. This document is available on the Health Quality & Safety Commission website, www.hqsc.govt.nz ISBN: 978-0-478-38555-7 (online) Citation: Health Quality & Safety Commission. 2013. Tall Man Lettering List Report. Wellington: Health Quality & Safety Commission. Crown copyright ©. This copyright work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 New Zealand licence. In essence, you are free to copy and distribute the work (including other media and formats), as long as you attribute the work to the Health Quality & Safety Commission. The work must not be adapted and other licence terms must be abided. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/nz/ Copyright enquiries If you are in doubt as to whether a proposed use is covered by this licence, please contact: National Medication Safety Programme Team Health Quality & Safety Commission PO Box 25496 Wellington 6146 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Health Quality & Safety Commission acknowledges the following for their assistance in producing the New Zealand Tall Man lettering list: • The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care for advice and support in allowing its original work to be either reproduced in whole or altered in part for New Zealand as per its copyright1 • The Medication Safety and Quality Program of Clinical Excellence Commission, New South -

ICD-9/10 Mapping Spreadsheet

ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM Mappings for Audiology Related Disorders Updated 7/16/2015 Disclaimer: This product is NOT comprehensive and consists only of codes commonly related to audiology services. Mappings are only to ICD-10-CM codes, not ICD-10-PCS. Every effort was made to accurately map codes using detailed analysis. Keep in mind, however, that while many codes in ICD-9-CM map directly to codes in ICD-10, in some cases, additional clinical analysis may be required to determine which code or codes should be selected for your situation. Always review mapping results before applying them. ICD-9-CM ICD-9-CM Description ICD-10- ICD-10-CM Description Notes Code CM Code 315.32 Mixed receptive-expressive F80.2 Mixed receptive-expressive language language disorder disorder Central auditory processing Developmental dysphasia or aphasia, disorder receptive type Developmental Wernicke's aphasia Excludes1: central auditory processing disorder (H93.25), dysphasia or aphasia NOS (R47.-), expressive language disorder (F80.1), expressive type dysphasia or aphasia (F80.1), word deafness (H93.25) Excludes2: acquired aphasia with epilepsy [Landau-Kleffner] (G40.80-), pervasive developmental disorders (F84.-), selective mutism (F94.0), intellectual disabilities (F70-F79) H93.25 Central auditory processing disorder Congenital auditory imperception Word deafness Excludes1: mixed receptive-epxressive language disorder (F80.2) 380.00 Perichondritis of pinna, unspecified H61.001 Unspecified perichondritis of right external ear H61.002 Unspecified perichondritis -

Vestibular Neuritis and Labyrinthitis

Vestibular Neuritis and DISORDERS Labyrinthitis: Infections of the Inner Ear By Charlotte L. Shupert, PhD with contributions from Bridget Kulick, PT and the Vestibular Disorders Association INFECTIONS Result in damage to inner ear and/or nerve. ARTICLE 079 DID THIS ARTICLE HELP YOU? SUPPORT VEDA @ VESTIBULAR.ORG Vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis are disorders resulting from an 5018 NE 15th Ave. infection that inflames the inner ear or the nerves connecting the inner Portland, OR 97211 ear to the brain. This inflammation disrupts the transmission of sensory 1-800-837-8428 information from the ear to the brain. Vertigo, dizziness, and difficulties [email protected] with balance, vision, or hearing may result. vestibular.org Infections of the inner ear are usually viral; less commonly, the cause is bacterial. Such inner ear infections are not the same as middle ear infections, which are the type of bacterial infections common in childhood affecting the area around the eardrum. VESTIBULAR.ORG :: 079 / DISORDERS 1 INNER EAR STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION The inner ear consists of a system of fluid-filled DEFINITIONS tubes and sacs called the labyrinth. The labyrinth serves two functions: hearing and balance. Neuritis Inflamation of the nerve. The hearing function involves the cochlea, a snail- shaped tube filled with fluid and sensitive nerve Labyrinthitis Inflamation of the labyrinth. endings that transmit sound signals to the brain. Bacterial infection where The balance function involves the vestibular bacteria infect the middle organs. Fluid and hair cells in the three loop-shaped ear or the bone surrounding semicircular canals and the sac-shaped utricle and Serous the inner ear produce toxins saccule provide the brain with information about Labyrinthitis that invade the inner ear via head movement. -

Vestibular Neuritis, Labyrinthitis, and a Few Comments Regarding Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss Marcello Cherchi

Vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis, and a few comments regarding sudden sensorineural hearing loss Marcello Cherchi §1: What are these diseases, how are they related, and what is their cause? §1.1: What is vestibular neuritis? Vestibular neuritis, also called vestibular neuronitis, was originally described by Margaret Ruth Dix and Charles Skinner Hallpike in 1952 (Dix and Hallpike 1952). It is currently suspected to be an inflammatory-mediated insult (damage) to the balance-related nerve (vestibular nerve) between the ear and the brain that manifests with abrupt-onset, severe dizziness that lasts days to weeks, and occasionally recurs. Although vestibular neuritis is usually regarded as a process affecting the vestibular nerve itself, damage restricted to the vestibule (balance components of the inner ear) would manifest clinically in a similar way, and might be termed “vestibulitis,” although that term is seldom applied (Izraeli, Rachmel et al. 1989). Thus, distinguishing between “vestibular neuritis” (inflammation of the vestibular nerve) and “vestibulitis” (inflammation of the balance-related components of the inner ear) would be difficult. §1.2: What is labyrinthitis? Labyrinthitis is currently suspected to be due to an inflammatory-mediated insult (damage) to both the “hearing component” (the cochlea) and the “balance component” (the semicircular canals and otolith organs) of the inner ear (labyrinth) itself. Labyrinthitis is sometimes also termed “vertigo with sudden hearing loss” (Pogson, Taylor et al. 2016, Kim, Choi et al. 2018) – and we will discuss sudden hearing loss further in a moment. Labyrinthitis usually manifests with severe dizziness (similar to vestibular neuritis) accompanied by ear symptoms on one side (typically hearing loss and tinnitus). -

Package Leaflet: Information for the User Hydroxyzine Bluefish 25 Mg

Package leaflet: Information for the user Hydroxyzine Bluefish 25 mg film-coated tablets hydroxyzine hydrochloride Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start using this medicine because it contains important information for you. - Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. - If you have any further questions, ask your doctor or pharmacist. - This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same as yours. - If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet 1. What Hydroxyzine Bluefish is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you use Hydroxyzine Bluefish 3. How to use Hydroxyzine Bluefish 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Hydroxyzine Bluefish 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Hydroxyzine Bluefish is and what it is used for Hydroxyzine Bluefish blocks histamine, a substance found in body tissues. It is effective against anxiety, itching and urticaria. Hydroxyzine Bluefish is used to treat anxiety in adults itching (pruritus) associated with hives (urticaria) in adults adolescents and children of 5 years and above 2. What you need to know before you take Hydroxyzine Bluefish Do not take Hydroxyzine Bluefish - if you are allergic to hydroxyzine hydrochloride or any of the other ingredients of this medicine (listed in section 6) - if you are allergic (hypersensitive) to cetirizine, aminophylline, ethylenediamine or piperazine derivatives (closely related active substances of other medicines). -

Hearing Loss, Vertigo and Tinnitus

HEARING LOSS, VERTIGO AND TINNITUS Jonathan Lara, DO April 29, 2012 Hearing Loss Facts S Men are more likely to experience hearing loss than women. S Approximately 17 percent (36 million) of American adults report some degree of hearing loss. S About 2 to 3 out of every 1,000 children in the United States are born deaf or hard-of-hearing. S Nine out of every 10 children who are born deaf are born to parents who can hear. Hearing Loss Facts S The NIDCD estimates that approximately 15 percent (26 million) of Americans between the ages of 20 and 69 have high frequency hearing loss due to exposure to loud sounds or noise at work or in leisure activities. S Only 1 out of 5 people who could benefit from a hearing aid actually wears one. S Three out of 4 children experience ear infection (otitis media) by the time they are 3 years old. Hearing Loss Facts S There is a strong relationship between age and reported hearing loss: 18 percent of American adults 45-64 years old, 30 percent of adults 65-74 years old, and 47 percent of adults 75 years old or older have a hearing impairment. S Roughly 25 million Americans have experienced tinnitus. S Approximately 4,000 new cases of sudden deafness occur each year in the United States. Hearing Loss Facts S Approximately 615,000 individuals have been diagnosed with Ménière's disease in the United States. Another 45,500 are newly diagnosed each year. S One out of every 100,000 individuals per year develops an acoustic neurinoma (vestibular schwannoma). -

Hearing Loss

Randal W. Swenson, M.D. Joshua G. Yorgason, M.D. David K. Palmer, M.D. Wesley R. Brown, M.D. John E. Butler, M.D. Nancy J. Stevenson, PA-C Justin D. Gull, M.D. ENT SPECIALISTS Kristin G. Hoopes, PA-C www.entslc.com Hearing Loss Approximately one in ten persons in the United may result from blockage of the ear canal (wax), States has some degree of hearing loss. Hearing is from a perforation (hole) in the ear drum, or from measured in decibels (dB), and a hearing level of 0- infection or disease of any of the three middle ear 25 dB is considered normal hearing. Your level is: bones. With a conductive loss only, the patient will never go deaf, but will always be able to hear, either Right ear _______ dB Left ear _______dB with reconstructive ear surgery or by use of a properly fitted hearing aid. Some patients who are Hearing Severity / % Loss not candidates for surgery, may benefit from a new 25 dB (normal).….0% 65dB(Severe)……...60% technology, the Baha (bone-anchored hearing aid). 35 dB (mild)……..15% 75dB(Severe)……...75% When there is a problem with the inner ear or 45 dB (moderate)..30% >85dB (Profound)..>90% nerve of hearing, a sensori-neural hearing loss occurs. This is most commonly from normal aging, Normal speech discrimination is 88-100%. Yours is: is usually worse in high frequencies, and can progress to total deafness. Noise exposure is another Right ear _______ % Left ear_______% common cause of high frequency hearing loss. Patients with sensori-neural hearing loss usually complain of difficulty hearing in loud environments. -

Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops

PO BOX 13305 · PORTLAND, OR 97213 · FAX: (503) 229-8064 · (800) 837-8428 · [email protected] · WWW.VESTIBULAR.ORG Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops By Susan Pesznecker, RN; Legacy Clinical Research & Technology Center, Portland, Oregon with the Vestibular Disorders Association Endolymphatic hydrops is a disorder of controls are believed to be lost or the vestibular system. Although its damaged. This may cause the volume and underlying cause and natural history are concentration of the endolymph to unknown, it is believed to result from fluctuate in response to changes in the abnormalities in the quantity, body’s circulatory fluids and electrolytes. composition, and/or pressure of the endolymph (the fluid within the Symptoms endolymphatic sac, a compartment of the Symptoms typical of hydrops include inner ear). pressure or fullness in the ears (aural fullness), tinnitus (ringing or other noise Causes in the ears), hearing loss, dizziness, and Endolymphatic hydrops may be either imbalance. primary or secondary. Primary idiopathic endolymphatic hydrops (known as Diagnosis and testing Ménière’s disease) occurs for no known There is no vestibular or auditory test reason. Secondary endolymphatic that is diagnostic of endolymphatic hydrops appears to occur in response to hydrops. Diagnosis is clinical—based on an event or underlying condition. For the physician’s observations and on the example, it can follow head trauma or ear patient’s history, symptoms, and surgery, and it can occur with other inner symptom pattern. The clinical diagnosis ear disorders, allergies, or systemic may be strengthened by the results of disorders (such as diabetes or certain tests. For example, certain autoimmune disorders). -

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Cr

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Crizotinib (PF-02341066) 1 4 55 Docetaxel 1 5 98 Anastrozole 1 6 25 Cladribine 1 7 23 Methotrexate 1 8 -187 Letrozole 1 9 65 Entecavir Hydrate 1 10 48 Roxadustat (FG-4592) 1 11 19 Imatinib Mesylate (STI571) 1 12 0 Sunitinib Malate 1 13 34 Vismodegib (GDC-0449) 1 14 64 Paclitaxel 1 15 89 Aprepitant 1 16 94 Decitabine 1 17 -79 Bendamustine HCl 1 18 19 Temozolomide 1 19 -111 Nepafenac 1 20 24 Nintedanib (BIBF 1120) 1 21 -43 Lapatinib (GW-572016) Ditosylate 1 22 88 Temsirolimus (CCI-779, NSC 683864) 1 23 96 Belinostat (PXD101) 1 24 46 Capecitabine 1 25 19 Bicalutamide 1 26 83 Dutasteride 1 27 68 Epirubicin HCl 1 28 -59 Tamoxifen 1 29 30 Rufinamide 1 30 96 Afatinib (BIBW2992) 1 31 -54 Lenalidomide (CC-5013) 1 32 19 Vorinostat (SAHA, MK0683) 1 33 38 Rucaparib (AG-014699,PF-01367338) phosphate1 34 14 Lenvatinib (E7080) 1 35 80 Fulvestrant 1 36 76 Melatonin 1 37 15 Etoposide 1 38 -69 Vincristine sulfate 1 39 61 Posaconazole 1 40 97 Bortezomib (PS-341) 1 41 71 Panobinostat (LBH589) 1 42 41 Entinostat (MS-275) 1 43 26 Cabozantinib (XL184, BMS-907351) 1 44 79 Valproic acid sodium salt (Sodium valproate) 1 45 7 Raltitrexed 1 46 39 Bisoprolol fumarate 1 47 -23 Raloxifene HCl 1 48 97 Agomelatine 1 49 35 Prasugrel 1 50 -24 Bosutinib (SKI-606) 1 51 85 Nilotinib (AMN-107) 1 52 99 Enzastaurin (LY317615) 1 53 -12 Everolimus (RAD001) 1 54 94 Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506) 1 55 24 Thalidomide 1 56 40 Tivozanib (AV-951) 1 57 86 Fludarabine