Williams College Libraries Copyright Assignment And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hclassification

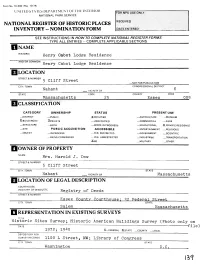

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATHS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Henry Cabot Lodge Residence AND/OR COMMON Henry Cabot Lodge Residence 5 Cliff Street .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Nahant VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Essex 009 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION -XNO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Harold J. Dow STREET & NUMBER 5 Cliff Street CITY, TOWN STATE Nahant VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Essex County Courthouse: ^2 Federal Street CITY, TOWN STATE Salem Massachusetts I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey; Historic American Buildings Survey (Photo only on DATE ————————————————————————————————————file) 1972; 19^0 X_FEDERAL 2LSTATE _COUNTY _J_OCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS 1100 L Street, NW; Library of Congress Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 3C ORIGINAL SITE X_QOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE This two-story, hip-roofed, white stucco-^covered, lavender- trimmed, brick villa is the only known extant residence associated with Henry Cabot Lodge. -

John Davis Lodge Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft9c6007r1 Online items available Register of the John Davis Lodge papers Finding aid prepared by Grace Hawes and Katherine Reynolds Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 1998 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the John Davis Lodge 86005 1 papers Title: John Davis Lodge papers Date (inclusive): 1886-1987 Collection Number: 86005 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 288 manuscript boxes, 27 oversize boxes, 3 cubic foot boxes, 1 card file box, 3 album boxes, 121 envelopes, 2 sound cassettes, 1 sound tape reel, 1 sound disc(156.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, speeches and writings, dispatches, reports, memoranda, clippings, other printed matter, photographs, sound recordings, and motion picture film relating to the Republican Party, national and Connecticut politics, and American foreign relations, especially with Spain, Argentina and Switzerland. Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. Creator: Lodge, John Davis, 1903-1985 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access Boxes 310-311 closed. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1986. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], John Davis Lodge papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Alternate Forms Available Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. -

Good-Bye to All That: the Rise and Demise of Irish America Shaun O'connell University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected]

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 9 6-21-1993 Good-bye to All That: The Rise and Demise of Irish America Shaun O'Connell University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the Nonfiction Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation O'Connell, Shaun (1993) "Good-bye to All That: The Rise and Demise of Irish America," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 9: Iss. 1, Article 9. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol9/iss1/9 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Good-bye to The Rise and All That Demise of Irish America Shaun O'Connell The works discussed in this article include: The Rascal King: The Life and Times of James Michael Curley 1874-1958, by Jack Beatty. 571 pages. Addison -Wesley, 1992. $25.00. JFK: Reckless Youth, by Nigel Hamilton. 898 pages. Random House, 1992. $30.00. Textures of Irish America, by Lawrence J. McCaffrey. 236 pages. Syracuse University Press, 1992. $29.95. Militant and Triumphant: William Henry O'Connell and the Catholic Church in Boston, by James M. O'Toole. 324 pages. University of Notre Dame Press, 1992. $30.00. When I was growing up in a Boston suburb, three larger-than-life public figures defined what it meant to be an Irish-American. -

H-Diplo ROUNDTABLE XXII-30

H-Diplo ROUNDTABLE XXII-30 Luke A. Nichter. The Last Brahmin: Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. and the Making of the Cold War. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020. ISBN: 9780300217803 (hardcover, $37.50). 8 March 2021 | https://hdiplo.org/to/RT22-30 Editor: Diane Labrosse | Production Editor: George Fujii Contents Introduction by Jessica Elkind, San Francisco State University ..................................................................................... 2 Review by John Milton Cooper, Jr., University of Wisconsin-Madison, Emeritus ..................................................... 5 Review by Lloyd Gardner, Rutgers University .................................................................................................................... 11 Review by Sophie Joscelyne, University of Sussex ........................................................................................................ 15 Response by Luke A. Nichter, Texas A&M University–Central Texas ....................................................................... 18 H-Diplo Roundtable XXII-30 Introduction by Jessica Elkind, San Francisco State University In his engaging new book, The Last Brahmin, Luke Nichter presents a compelling biography of Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. Nichter argues that Lodge was one of the most influential, though often overlooked, figures in the history of twentieth- century U.S. foreign relations and that “the story of [Lodge’s] life and career illustrates America’s coming of age as a superpower” (2). Throughout the book, Nichter emphasizes Lodge’s -

A District Represented by Mavericks

CHAPTER THREE A District Represented by Mavericks f there is one word that best describes those individuals who have Ibeen elected to the United States Congress from Connecticut’s fourth congressional district, that word, plain and simple, is “maverick.” Indeed, Lowell P. Weicker, Jr., who represented the fourth district prior to his election to the United States Senate, titled his autobiography “Maverick” to underscore his conduct and orientation during his years in public office.1 Political mavericks, however, have ruled the fourth district long before the appearance of the contentious Weicker. Clare Boothe Luce (1943-47) Clare Boothe Luce, who served in Congress from 1943-47, is perhaps the first representative from Connecticut’s fourth congressional district to deserve the maverick moniker. The fact that she was not only a woman but also a woman elected to Congress during World War II speaks volumes about the independence and resolve of this quite extraordinary individual. A woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives at a time when so few women had even considered entering politics, and during a world war no less, is in itself quite remarkable. During Luce’s first term in Congress slightly less than two percent of House members were women, while during her second term slightly less than three percent of the House consisted of females. There were no women in A DISTRICT REPRESENTED BY MAVERICKS 37 the United States Senate during Luce’s two congressional terms.2 Prior to her election to Congress, Luce was a writer, accomplished and renowned playwright, journalist, and a widely traveled and astute foreign correspondent. -

Connecticut Daily Campus Serving Storrs Since 1896

Connecticut Daily Campus Serving Storrs Since 1896 MONDAY, OCTOBER 26. 1964 VOL. LXIX. NO. 27 STORRS. CONNECTICUT University Releases Fraternity Study Committee Report Recommendations Include Alumni Advisors or And End Of Selection Policy In Towers According to the report, other University Board of Trustees re- By ARLENE BRYANT houses are in danger of falling cognizing the interfraternlty A twelve-point plan to rebuild below the required minimum of Council and giving it the authority the fraternity system here at 40 members. to establish standards for the UConn was released yesterday Citing asteadily declining mem- granting and the withdrawal of in the Fraternity Study Com- bership since 1959, the Com- recognition. mittee Report. mittee placed the cause of the In compiling their report, Fra- The report calls for the es- present weakened fraternity sys- ternity Study Committee met with tablishment of an active alumni tem on ineffective guidance and officers of national fraternities advisory group by each fra- leadership. which have local campus ternity, the suspension of the chapters, and with University 40-man minimum count for the If the rehabilitation program Is administrators. The members academic year 1964-65, ousting enacted, four of the five fra- also studied reports on fra- of the Towers' "Selection" com- ternities currently housed In the ternity problems at other col- mittees, and the appointment of Towers would be moved to the leges and universities. a University Coordinator of Fra- Fraternity Quadrangle. The Committee Includes repre- ternity Affairs. Independent men's units In sentatives of the Fraternities The Committee, appointed by the Towers Residence Area would and Independent students, the President Babbidge last March no longer maintain "Selection" Board of Trustees, the Faculty to make a thorough study of the committees which currently de- and the Alumni. -

White House Special Files Box 47 Folder 9

Richard Nixon Presidential Library White House Special Files Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date Document Type Document Description 47 9 n.d. Report Richard M. Nixon Handbook. Re: Reliable and useful Information about Vice President Richard M. Nixon. 8 Pages. 47 9 n.d. Memo Remarks on Palestine by Henry Cabot Lodge. 3 Pages. 47 9 8/27/1960 Brochure Israel and the Middle East a Message from Vice President Richard Nixon to the Annual Convention of the Zionist Organization of America. 5 Pages. 47 9 8/1960 Report Report of a Survey made by the American Jewish Committee. 2 Pages. 47 9 n.d. Memo Eisenhower-Nixon record on Civil Rights. Re: Summary of Administration record in field of civil rights. 1 Page. 47 9 10/13/1952 Report Speakers Kit. Excerpts from John P. Millan's Articles "Massachusetts, Liberal and Corrupt". 2 Pages. Wednesday, June 20, 2007 Page 1 of 2 Box Number Folder Number Document Date Document Type Document Description 47 9 n.d. Letter Fill in the blank letter Re: Henry Cabot Lodge's position on the Jewish People. 4 Pages. 47 9 8/18/1960 Newsletter Congressional Record newsletter. Re: The Religious Issue in the Presidential Campaign. 1 Page. 47 9 n.d Brochure Here's what the democrats think about Kennedy! Cover scanned only. 47 9 n.d. Memo Re: front page story which appeared on September 27, 1960, in the Day Jewish Journal, New York's Yiddish daily. 1 Page. 47 9 9/1/1960 Newspaper Reprint from the New York Times. -

Oral History Interview – 5/19/1964 Administrative Information

Frank E. Dobie Oral History Interview – 5/19/1964 Administrative Information Creator: Frank E. Dobie Interviewer: Ed Martin Date of Interview: May 19, 1964 Place of Interview: Boston, Massachusetts Length: 12 pages Biographical Note Dobie, Massachusetts political figure and Kennedy campaign worker (1946), discusses John F. Kennedy’s (JFK) 1946 congressional campaign, JFK’s decision to run for the Senate in 1952, and his visits with JFK in the hospital, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed on May 29, 1969, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. -

IRREGULARITIES at ELECTION ARE ALLEGED FOE of LEAGUE DEAD Active Organization BROOKHART-STECK for the Red Cross VOTE BEING COUNTED | DES MOINES

Red Cross Roll Call Will Be Started Here Tomorrow | Amlum iEttatum northeast Nans £mwinds. VOL. XLIV. No. 15. PERTH Eighteen cwn a week AMBOY, N. J., MONDAY, NOVEMBER 10,1924. THREEiuiuvo v£.nioPFNTS _. Deileerea Br Carrier __ No Hunting Edict Obeyed, But Some Shots Are Heard I .IRREGULARITIES AT ELECTION ARE ALLEGED FOE OF LEAGUE DEAD Active Organization BROOKHART-STECK For The Red Cross VOTE BEING COUNTED | DES MOINES. Iowa, Nov. 10.— Determination of the official result of the senatorial contest between ROLL CALL CHAIRMAN Drive Will Be Ended Thanks- Senator Smith W. Brookhart. Re- publican. and Daniel F. Steck. Dem- TO INVESTIGATE _ Fraser ocrat. was begun today when boards giving—William ! of supervisors in each of Iowa’s 99 I Is Roll Call Chairman Grief Are Heard Around Outskirts Memorial Service Last Night counties met to count the votes of Republican State Committee- Washington Expresses Tuesday's election. The official If | man Schneider Will Make I at Passing of Senate of New Brunswick and at Temple Was Most count was being tabulated here. j In addition to the monster parade On the face of unofficial returns, 9 Leade1 Around Woodbridge tomorrow night, Armistice Day in ] Impressive Event Senator Brookhart was leading Stock Specific Charges this city tomorrow will be marked by: by 1,025 votes, out of a total of the start of the seventh annual Roll! nearly 900,000 cast. PRESIDENT’S STATE EDICT STANDS Call drive of the Red Cross. RABBI BRENNER SPEAKER If was believed that the official PROBE THREE DISTRICTS I STATEMENT Everything is in readiness for the + canvass would require two days. -

Oral History Interview – JFK#1, 06/01/1964 Administrative Information

William F. Kelly Oral History Interview – JFK#1, 06/01/1964 Administrative Information Creator: William F. Kelly Interviewer: Ed Martin Date of Interview: June 1, 1964 Place of Interview: Boston, Massachusetts Length: 21 pages Biographical Note Kelly, Massachusetts political figure, district secretary for East Boston during John F. Kennedy's first congressional campaign (1946) and Senate campaign (1952), discusses his personal memories of JFK and campaigning in East Boston, among other issues. Access Open Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed March 13, 1968 copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. -

America's Nightmare the Rise and Fall of the Federal Elections Bill

America’s Nightmare The Rise and Fall of the Federal Elections Bill and the Making of an American Ethos By Coda Danu-Asmara Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor Arts In the Department of History at Brown University Thesis Advisor: Richard Meckel April 6th, 2018 ii iii To my beloved. iv Table of Contents Acknowledgements v Preface vi Introduction 1 Chapter One 13 Chapter Two 47 Conclusion 76 Bibliography 82 v Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Richard Meckel, for providing me with support, guidance, and jokes about my lazy generation over the year long process of writing a thesis. I would like to thank Professors Ethan Pollock and Naoko Shibusawa for running the prospectus and thesis classes, respectively. I would also like to thank Professors Linford Fisher, Francoise Hamlin, Stephen Kidd, Emily Owens, Lukas Rieppel, and Michael Vorenberg for providing me early feedback and resources when I was still writing a prospectus. I would like to thank all of my peers in History 1992, 1993, and 1994. It’s been a pleasure to see everybody’s ideas grow into something uniquely their own. In particular, I would like to thank my group members Zoë Gilbard, Sarah Novicoff, and Isabella Kres- Nash for their invaluable comments and critiques, and Barry Thrasher, for reading over a draft of my thesis and helping me structure into what it is now. I would also like to thank Henry Hauser for reading a draft and helping me think of a witty and pithy title. -

Jones-William-B.2010.Toc 2.Pdf

Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR WILLIAM B. JONES Interviewed by: Kenneth Brown and Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: June 24, 2010 Copyright 2012 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in California Ancestry Sc ooling Race relations Tuskegee Airmen University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) University College, Sout ampton, England University of California (UC) Law Sc ool Kappa Alp a Psi fraternity Joanne ,arland, wife A. P ilip Randolp Dr. Benjamin .ays Nu Beta Epsilon fraternity .arriage Los Angeles, California0 Law Practice 112341122 Partner, 5illiam R. Freeman Los Angeles, California6 Law practice 112241172 Local politics Democratic Party politics .r. Earl ,rant Legal cases Founding .ember, Los Angeles 5orld Affairs Council S:kou Tour: visit Entered t e State Department 1172 State Department6 Bureau of Education and Culture 117241171 C ief, 5est Coast and .ali Programs (117241174) Deputy Dir., African Programs (117441177) Director, Program Evaluation Staff (117741171 1 Deputy Assistant Secretary for Education and Cultural Affairs (117141173) Life in 5as ington, DC Black social groups Our Kind of People Sigma P i Pi (=t e Boul:) Family Sc ooling of c ildren American Society of African Culture (A.SAC) Fred Irving Leader Program Content Fulbrig t Relations wit USIA Congressman Jo n Rooney President Kennedy Crown Prince of Et iopia visit T urgood .ars all Jesse Owens Dar es Salaam anti4Britis riots .uslin Brot er ood, Sudan Averell Harriman ,uerilla movements