Concord Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ramsey Scott, Which Was Published in 2016

This digital proof is provided for free by UDP. It documents the existence of the book The Narco- Imaginary: Essays Under The Influence by Ramsey Scott, which was published in 2016. If you like what you see in this proof, we encourage you to purchase the book directly from UDP, or from our distributors and partner bookstores, or from any independent bookseller. If you find our Digital Proofs program useful for your research or as a resource for teaching, please consider making a donation to UDP. If you make copies of this proof for your students or any other reason, we ask you to include this page. Please support nonprofit & independent publishing by making donations to the presses that serve you and by purchasing books through ethical channels. UGLY DUCKLING PRESSE uglyducklingpresse.org THE NARCO IMAGINARY UGLY DUCKLING PRESSE The Narco-Imaginary: Essays Under The Influence by Ramsey Scott (2016) - Digital Proof THE NARCO- IMAGINARY Essays Under the Influence RAMSEY SCOTT UDP :: DOSSIER 2016 UGLY DUCKLING PRESSE The Narco-Imaginary: Essays Under The Influence by Ramsey Scott (2016) - Digital Proof THE Copyright © 2016 by Ramsey Scott isbn: 978-1-937027-44-5 NARCO- DESIGN AnD TYPEsETTING: emdash and goodutopian CoVEr PRINTING: Ugly Duckling Presse IMAGINARY Distributed to the trade by SPD / Small Press Distribution: 1341 Seventh Street, Berkeley, CA 94710, spdbooks.org Funding for this book was provided by generous grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, and the Department of Cultural Affairs -

Southern Palm Zen News

Southern Palm Zen News December 2011 Volume 5, Number 12 In This Issue Shuso for Zochi Shuso Hossen for Winter Special Events Prison Outreach 2011-12 Calendar Gary Zochi Faysash Sangha Bulletin Board Saturday, December 17, 2011 Our Website Shuso Hossen or Dharma Combat is a ceremonial rite- www.floridazen.com of-passage marking a student’s promotion to the rank of senior student. look here for recommended At Hossen, the Shuso gives his first dharma talk and takes questions resources and readings for from the community in a ceremonial conversation. Zochi’s dharma talk students of zen will arise from insights obtained while studying the koan “Mind is Buddha”. Our Schedule Please read the koan below and consider what questions you might ask Tuesday & Thursday him on that day. Also, you are invited to present a poem or short piece Morning of prose or some other original work to honor the Shuso. Zazen 7:00 a.m. – 8:00 a.m. Schedule for Saturday, December 17, 2011 7:15–7:30 a.m. SERVICE Short Break Wednesday Evening 7:30–8:00 ZAZEN 8:40 – 9:00 SET UP FOR SHUSO HOSSEN Orientation to Zen & 8:00–8:10 KINHIN-INTERVIEWS 9:00 – 10:00 SHUSO HOSSEN Meditation: CEREMONY 5:30 – 6:00 p.m. 8:10–8:40 ZAZEN-FOUR VOWS 10:00 - 11:00 BREAKFAST Study Group To help us plan seating and food, please RSVP to [email protected]. 6:00 – 7:00 p.m. Service & Zazen 7:00 – 8:00 p.m. KOAN# 30 FROM THE GATELESS BARRIER: MIND IS BUDDHA Saturday Morning THE CASE Service & Zazen 7:15 – 9:10 a.m. -

EDITORIAL Sages of the Profession: Celebration of Our Heritage

EDITORIAL Sages of the Profession: Celebration of our Heritage Gerald T. Powers Virginia Majewski Special Issue Co-Editors The Indiana University School of Social Work recently celebrated its 100-year anniversary as the oldest school of social work continuously affiliated with a university. That seminal occasion served as a compelling reminder of the extraordinary history of our profession and its relentless efforts on behalf of the vulnerable, oppressed and disadvantaged members of society. For more than a decade, the School’s journal Advances in Social Work has been devoted to the dissemination of theory and research that supports these efforts of social work educators and practitioners. Thus it seemed only appropriate that we devote a special issue of Advances to a retrospective exploration of some of the critical events in the history of the profession that have contributed to and help shape our present understanding of social work practice and education. The intent of this special issue is to chronicle the rich heritage of the social work profession and its educational initiatives as seen through the eyes of those who have actually lived and contributed to that heritage. Accordingly, the editorial board felt that the best way to document some of these critical events would be to invite a group of nationally recognized scholars to provide first-person, eyewitness accounts of their observations and direct involvement with the events as they unfolded. The initial challenge in creating this special issue was to identify a representative group of social work “sages,” that is, those individuals with the professional and academic credentials that would qualify them to speak authoritatively about the landmark events and challenges in the history of the profession. -

What Keeps Us Going: Factors That Sustain U.S

WHAT KEEPS THEM GOING: FACTORS THAT SUSTAIN U.S. WOMEN'S LIFE-LONG PEACE AND SOCIAL JUSTICE ACTIVISM SUSAN MCKEVITT A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Ph.D. in Leadership & Change Program of Antioch University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2010 This is to certify that the dissertation entitled: WHAT KEEPS THEM GOING: FACTORS THAT SUSTAIN U.S. WOMEN'S LIFE-LONG PEACE AND SOCIAL JUSTICE ACTIVISM prepared by Susan McKevitt is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Leadership and Change. Approved by: ________________________________________________________________________ Laurien Alexandre, Ph.D., Chair Date ________________________________________________________________________ Jon Wergin, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________________________ Philomena Essed, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________________________ Bettina Aptheker, Ph.D., External Reader Date Copyright 2010 Susan McKevitt All rights reserved Dedication This study is dedicated to all the peace and social justice activists who have been, now are, and are yet to be. For those who have been, know that your struggles were not in vain for they bore fruit of which you never could have dreamed. For those currently in the fray, know that the role you play in the continuum of creating peace and social justice is honoring of those who have come before and critical for those yet to come. You, too, may not see the fruits of your labors, yet you persist anyway. And, for those who are contemplating joining this glorious community of activists, know that your participation will feed your souls, lighten our hearts, and help us to keep going as your vitality and exuberance will strengthen us. -

Anglican Catholicism Send This Fonn Or Call Us Toll Free at 1-800-211-2771

THE [IVING CHURCH AN INDEPENDENT WEEKLY SUPPORTING CATHOLIC ANGLICANISM • NOVEMBER 8 , 2009 • $2.50 Rome Welcomes Anglican Catholicism Send this fonn or call us toll free at 1-800-211-2771. I wish to give (check appropriate box and fill in) : My name: D ONE one-year gift subscription for $38.00 (reg. gift sub. $40.00) D TWO one-year gift subscriptions for $37 .00 each Name ------------''---------- Addres s __ _ __________ _ _____ _ ($37.00 X 2 = $74.00) THREE OR MORE one-year gift subscriptions for $36.00 each City/State/Zip ____ _ __________ _ _ _ D ($36.00 X __ = $._ _ ____, Phone _ __ ________________ _ Please check one: 0 One-time gift O Send renewal to me Email ____ _ ______________ _ Makechecks payable to : My gift is for: The living Church P.O.Box 514036 Milwaukee, WI 53203-3436 31.rec"-------------- Foo,ign postage extra First class rar,s available I VISA I~ ~ .,__· _c.· __________ _ D Please charge my credit card $ ____ _ ~ City/Stite/Zip __ _ _______ _ NOTE: PLEASE Fll.L IN CREDIT CARD BILLINGINFORMATION BELOW IF DIFFERENT FROM ADDRESS ABOVE. Phone Billing Address ________ _ _ _ _ _ ____ _ Bi.Bing City Please start this gift subscription O Dec. 20, 2009 Credit Card # _ _ _ _ _ __ _ _ Exp. Sign gift card _ _________ _ THELIVING CHURCH magazine is published by the Living Church Foundation, LIVINGCHURCH Inc. The historic mission of the Living Church Foundation is to promote and M independent weekly serving Episcopalians since1878 support Catholic Anglicanism within the Episcopal Church. -

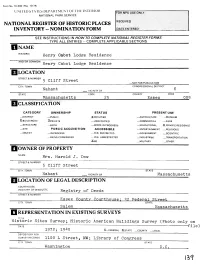

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATHS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Henry Cabot Lodge Residence AND/OR COMMON Henry Cabot Lodge Residence 5 Cliff Street .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Nahant VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Essex 009 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION -XNO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Harold J. Dow STREET & NUMBER 5 Cliff Street CITY, TOWN STATE Nahant VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Essex County Courthouse: ^2 Federal Street CITY, TOWN STATE Salem Massachusetts I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey; Historic American Buildings Survey (Photo only on DATE ————————————————————————————————————file) 1972; 19^0 X_FEDERAL 2LSTATE _COUNTY _J_OCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS 1100 L Street, NW; Library of Congress Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 3C ORIGINAL SITE X_QOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE This two-story, hip-roofed, white stucco-^covered, lavender- trimmed, brick villa is the only known extant residence associated with Henry Cabot Lodge. -

John Davis Lodge Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft9c6007r1 Online items available Register of the John Davis Lodge papers Finding aid prepared by Grace Hawes and Katherine Reynolds Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 1998 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the John Davis Lodge 86005 1 papers Title: John Davis Lodge papers Date (inclusive): 1886-1987 Collection Number: 86005 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 288 manuscript boxes, 27 oversize boxes, 3 cubic foot boxes, 1 card file box, 3 album boxes, 121 envelopes, 2 sound cassettes, 1 sound tape reel, 1 sound disc(156.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, speeches and writings, dispatches, reports, memoranda, clippings, other printed matter, photographs, sound recordings, and motion picture film relating to the Republican Party, national and Connecticut politics, and American foreign relations, especially with Spain, Argentina and Switzerland. Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. Creator: Lodge, John Davis, 1903-1985 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access Boxes 310-311 closed. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1986. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], John Davis Lodge papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Alternate Forms Available Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. -

Roberto Sierra's Missa Latina: Musical Analysis and Historical Perpectives Jose Rivera

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Roberto Sierra's Missa Latina: Musical Analysis and Historical Perpectives Jose Rivera Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC ROBERTO SIERRA’S MISSA LATINA: MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND HISTORICAL PERPECTIVES By JOSE RIVERA A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 Copyright © 2006 Jose Rivera All Rights Reserved To my lovely wife Mabel, and children Carla and Cristian for their unconditional love and support. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work has been possible with the collaboration, inspiration and encouragement of many individuals. The author wishes to thank advisors Dr. Timothy Hoekman and Dr. Kevin Fenton for their guidance and encouragement throughout my graduate education and in the writing of this document. Dr. Judy Bowers, has shepherd me throughout my graduate degrees. She is a Master Teacher whom I deeply admire and respect. Thank you for sharing your passion for teaching music. Dr. Andre Thomas been a constant source of inspiration and light throughout my college music education. Thank you for always reminding your students to aim for musical excellence from their mind, heart, and soul. It is with deepest gratitude that the author wishes to acknowledge David Murray, Subito Music Publishing, and composer Roberto Sierra for granting permission to reprint choral music excerpts discussed in this document. I would also like to thank Leonard Slatkin, Norman Scribner, Joseph Holt, and the staff of the Choral Arts Society of Washington for allowing me to attend their rehearsals. -

Comparing the 16Th and 17Th Korean Presidential Elections - Candidate Strengths, Campaign Issues, and Region-Centered Voting -

33 〈特集1 2007年韓国大統領選挙〉 Comparing the 16th and 17th Korean Presidential Elections - Candidate Strengths, Campaign Issues, and Region-Centered Voting - Byoung Kwon Sohn th th Abstract: This article aims at comparing the 16 and 17 presidential elections in terms of the number of major competitive candidates, candidates’ strengths, major campaign issues and the effect of region-centered voting. Among other things, both elections are commonly characterized by the major party’s presidential candidates being selected via U.S. style primary, which had been first adopted in the 2002 presidential election. Rampantly strong region- centered voting pattern counts among continuities as well, while in 2002 the effect of region- centered voting appeared in a somewhat mitigated form. Contrasts, however, loom rather large between the two elections. First, while the 2002 election was a two-way election between NMDP and GNP, the 2007 election was a three-way election among DNP, GNP, and one competitive independent candidate. Second, strong anti-Americanism, relocation of Korean capital, and younger generation’s activism counted among major issues and features in 2002, while in 2007 voters’ anger at the incumbent president and their ardent hope for economic recovery were atop campaign issues. Third, strong as region-centered voting may be across the two elections, its effect was somewhat mitigated in the 2002 presidential election, because NMDP candidate Roh’s hometown was in Pusan, where GNP had traditionally ruled as a regional hegemonic party. Lastly, in 2002 Roh was able to get elected partly due to his image as a reform-oriented, non-mainstream, anti-American stance politician. -

The BG News February 11, 1994

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-11-1994 The BG News February 11, 1994 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 11, 1994" (1994). BG News (Student Newspaper). 5650. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/5650 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ^ The BG News "A Commitment to Excellence" Friday, February 11, 1994 Bowling Green, Ohio Volume 77, Issue 96 Train strikes student's vehicle Railway crossing collision kills senior criminal justice major by David Coehrs and Michael traveling at approximately 30 Zawacki to 35 mph when the accident The BC News occured, said BUI Aldridge, conductor. A University student was "I saw him hit the brakes killed Thursday morning and tried to stop, but he slid when his car was struck by a out in front of us," Aldridge train at the Pike Street rail- said. road crossing. Rick Engle, public works in- Stephen Seely, a 23-year-old spector, said he witnessed the senior criminal justice major train hit the passenger side of from Toledo, lost control of his Seely's car. red Honda Civic hatchback "The car was carried for and slid into the path of the about 500 feet, from Pike oncoming train at approxi- Street to Court Street," Engle mately 9:15 am., according to said. -

CADIZ ®S5u V RD the Hometown Newspaper for Trigg County Since 1881 Printed with Soy Ink

** it a- ■#* * * THE CADIZ ®S5u v RD The Hometown Newspaper for Trigg County since 1881 Printed with Soy Ink VOL. 112 NO. 22 COPYRIGHT © 1993, THE CADIZ RECORD, CADIZ, KENTUCKY JUNE 2, 1993 5 0 C E N T S Community welcomes Chelsea Industries Michigan manufacturer acquires spec building Three representatives of Chelsea Industries from Michigan were greeted by more than 200 Trigg County residents and government officials during the May 28 announcement that the automotive components manufacturer had acquired the vacant spec building in Indus trial Park #2. "There’s no shortfall of com munity support,” said Ron Thompson, Chelsea president and chief executive officer, at the new plant site. "Our thanks go to several people. This will be an exciting proposition for all of us." John Mayne, controller, and John Szalay, project manager, accompanied Thompson to Cadiz. In a written statem ent, Chelsea Industries is building its first satellite plant in Trigg County to meet the needs of an expanding customer base in the south. The manufacturer will spend an estimated $3 million for -• (Left photo) Cadiz Mayor Scott Sivills (left) equipment and renovation of presents the key to the city to Ron Thompson, president and chief the 40,000 square foot building. executive officer of Chelsea industries, during a press conference on The new industry reportedly May 28 announcing that Chelsea is locating a satellite plant in Trigg could be in operation in 90 days. County. (Above photo) Gov. Brereton Jones is greeted by Kenneth Guinn, chairman of the Trigg County Industrial Authority. See Industry, Page A-3 Bond reduction allowed for Brown; crime syndicate trial is postponed A Hopkinsville man accused tried at the same time, meaning amount. -

Regionalism in South Korean National Assembly Elections

Regionalism in South Korean National Assembly Elections: A Vote Components Analysis of Electoral Change* Eric C. Browne and Sunwoong Kim Department of Political Science Department of Economics University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee [email protected] [email protected] July 2003 * This paper was originally presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, San Francisco, 29 August – 2 September, 2001. We acknowledge useful comments and suggestions by the session participants, Ronald Weber and anonymous referees. Abstract We analyze emerging regionalism in South Korean electoral politics by developing a “Vote Components Analysis” and applying this technique to data from the eleven South Korean National Assembly elections held between 1963 and 2000. This methodology allows us to decompose the change in voting support for a party into separate effects that include measurement of an idiosyncratic regional component. The analysis documents a pronounced and deepening regionalism in South Korean politics since 1988 when democratic reforms of the electoral system were fully implemented. However, our results also indicate that regional voters are quite responsive to changes in the coalitions formed by their political leaders but not to the apparent mistreatment of, or lack of resource allocations to, specific regions. Further, regionalism does not appear to stem from age-old rivalries between the regions but rather from the confidence of regional voters in the ability of their “favorite sons” to protect their interests and benefit their regions. JEL Classification: N9, R5 Keywords: Regionalism, South Korea, Elections, Vote Components Analysis 2 1. INTRODUCTION The history of a very large number of modern nation-states documents a cyclical pattern of territorial incorporation and disincorporation in their political development.