A District Represented by Mavericks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

Health Sciences Alumni

Health Sciences Alumni Updated: 11/15/17 Allison Stickney 2018 High school science teaching Teach for America, Dallas-Fort Worth Sophia Sugar 2018 Research Assistant Nationwide Children’s Hosp., Columbus, OH Wanying Zhang 2017 Accelerated BSN, Nursing MGH Institute for Health Professions Kelly Ashnault 2017 Pharmacy Technician CVS Health Ian Grape 2017 Middle School Science Teacher Teach Kentucky Madeline Hobbs 2017 Medical Assistant Frederick Foot & Ankle, Urbana, MD Ryan Kennelly 2017 Physical Therapy Aide Professional Physical Therapy, Ridgewood, NJ Leah Pinckney 2017 Research Assistant UConn Health Keenan Siciliano 2017 Associate Lab Manager Medrobotics Corporation, Raynham, MA Ari Snaevarsson 2017 Nutrition Coach True Fitness & Nutrition, McLean VA Ellis Bloom 2017 Pre-medical fellowship Cumberland Valley Retina Consultants Elizabeth Broske 2017 AmeriCorps St. Bernard Project, New Orleans, LA Ben Crookshank 2017 Medical School Penn State College of Medicine Veronica Bridges 2017 Athletic Training UT Chattanooga, Texas A&M, Seton Hall Samantha Day 2017 Medical School University of Maryland School of Medicine Alexandra Fraley 2017 Epidemiology Research Assistant Department of Health and Human Services Genie Lavanant 2017 Athletic Training Seton Hall University Taylor Tims 2017 Nursing Drexel University, Johns Hopkins University Chase Stopyra 2017 Physical Therapy Rutgers School of Health Professions Madison Tulp 2017 Special education Teach for America Joe Vegso 2017 Nursing UPenn, Villanova University Nicholas DellaVecchia 2017 Physical -

Nominations Of: Ronald Sims, Fred P. Hochberg, Helen R

S. HRG. 111–173 NOMINATIONS OF: RONALD SIMS, FRED P. HOCHBERG, HELEN R. KANOVSKY, DAVID H. STEVENS, PETER KOVAR, JOHN D. TRASVIN˜A, AND DAVID S. COHEN HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON NOMINATIONS OF: RONALD SIMS, OF WASHINGTON, TO BE DEPUTY SECRETARY, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT FRED P. HOCHBERG, OF NEW YORK, TO BE PRESIDENT AND CHAIRMAN, EXPORT-IMPORT BANK HELEN R. KANOVSKY, OF MARYLAND, TO BE GENERAL COUNSEL, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT DAVID H. STEVENS, OF VIRGINIA, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR HOUSING–FEDERAL HOUSING COMMISSIONER, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT PETER KOVAR, OF MARYLAND, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR CONGRESSIONAL AND INTERGOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT JOHN D. TRASVIN˜ A, OF CALIFORNIA, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR FAIR HOUSING AND EQUAL OPPORTUNITY, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT DAVID S. COHEN, OF MARYLAND, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR TERRORIST FINANCING, DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY APRIL 23, 2009 Printed for the use of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs ( Available at: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate/senate05sh.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 53–677 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut, Chairman TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota RICHARD C. -

A Bibliography

Reno Divorce History – A Bibliography compiled by Mella Harmon Books - General Nonfiction and Miscellaneous Books and Chapters - Pre-1970 A to Z Directory Publishers 1930 A to Z Directory and Guide Book, 1929-1930. Reno Printing Company, Reno. 1933 A to Z Directory and Guide Book, 1932-1933. Reno Printing Company, Reno. Anonymous 1953 Fun in Reno and the Far West! Publisher unknown. Barnett, James Harwood 1939 Divorce and the American Divorce Novel, 1858-1937. Reissued 1968. Russell and Russell, New York. Bartlett, George 1931 Men, Women and Conflict. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, London. 1947 Is Marriage Necessary? Revised edition. Penguin Books, Inc., New York. Beebe, Lucius 1968 Reno: Specialization and Fun. In Strauss, Anselm L., The American City: A Sourcebook of Urban Imagery. Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago, 431-433. Bender-Moss Company 1942 Nevada Compiled Laws, Supplement 1931-1941. Bender-Moss Company, San Francisco. Bixler, W.K. 1964 The Life and Times of Clel Georgetta, a Pictorial Biography. Sierra Publications. Bolin, James H. 1924 Reno, Nevada, the Holy City of the World. Distributed by Bolin Publishing Co., Reno. Bond, George W. 1921 Six Months in Reno. Stanley Gibbons, Inc., New York. Clark, Walter Van Tilburg 1949 Reno: The State City. In Rocky Mountain Cities, edited by Ray B. West, Jr. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York. Curtis, Leslie 1912 Reno Reveries. Chas. E. Weck, Distributing Agent, Reno. 1924 Reno Reveries. Armanko Stationery Co., Reno. David, W. M. 1928 Ramblings through the Pines and Sage: A Series of One Day Tours out of Reno. W. M. David for Nevada State Automobile Association. -

Trinity Tripod, 1960-09-26

Inside Pages •Aisle Say' Goes Editorials Nightcl ubing. No Bottles Trough Windows I *By George' Begins Today, Polices: Interested Page 4. - drinify or Curious? Voi. LVUV, TRINITY COLLEGE, HARTFORD, CONN. MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 26, I960 Tabled Curriculum Revisions Dick, Cabot Victorious Face Oct. 15 Trustees Verdict Vernon St. Takes 135; SEPT. 22—The new curric-, the Trustees consider approv- ulum which last year was! ing - the curriculum at their Student Body Gives passed by the faculty and next meeting, Oct. 15. 23 Pledge Grow While tabled temporarily by the .Constuction on the North jTrrustees has not "been aban-1 Campus, a dormitory building jdoned, President Jacobs said i between Allen Place and Ver- GOP 371-142 Mandate i today. i non Street, will begin "as 5 Join D. Phi Splinter | He said only a few points! early this fall as possible," Dr. SEPT. 22—K the Trinity, i remain to be studied before J Jacobs said. College student body was aj1. Which candidate do vou favor for President? Vernon Street's Annual quest Fraternity Ruling- for now blood end or! last week political weathervane, tihe wor- j KENNEDY 142 NIXON 371 UNDECIDED 48. The struct urt will house Glum Spectators ries of Richard Nixon and his | 2. Which candidate will your parents most likely wild 136 students pledged Profs' Smut Pics some fraternity and unalfili- from 200 eligible. campaign staff would'be over. favor? j ated students who wish to be An overwhelming majority The three-week-old "Q.K.D," KENNEDY 103 NIXON 210 DON'T KNOW 104 Prompt Smith Wit ; assigned there. -

"Always Good to Keep the Record Straight" - Bernard Shaw Reporting on the IRS Clearing Gingrich on CNN in February of 1999

TO: INTERESTED PARTIES FROM: R.C. Hammond, Press Secretary SUBJECT: Fact Sheet: Newt Gingrich Ethics Committee Investigation In an Interview with Talking Points Memo today former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi implied she knows "a lot about him" [Newt Gingrich] that is currently not a matter of public record. How soon the Congresswoman forgets that 83 of the 84 politically motivate charges filed against Speaker Gingrich were dismissed. And furthermore, the IRS found that Newt did nothing wrong! As CNN's Bernard Shaw reported, "Always Good to Keep the Record Straight." We agree. "Always Good To Keep The Record Straight" - Bernard Shaw reporting on the IRS clearing Gingrich on CNN in February of 1999 Fact Sheet on the Ethics Committee Investigation of Newt Gingrich and the Ensuing Decision by the IRS that Gingrich’s Activities Were Perfectly Legal 84 politically motivated ethics charges were filed against Newt when he was Speaker of the House regarding the use of tax exempt funds for a college course he taught titled “Renewing American Civilization.” 83 of the 84 were found to be without merit. The remaining charge had to do with contradictory documents prepared by Newt’s lawyer supplied during the course of the investigation. Newt took responsibility for the error and agreed to reimburse the committee the cost of the investigation into that discrepancy. The agreement specifically noted the payment was not a fine. In 1999, after a 3 ½ year investigation, the Internal Revenue Service (under President Bill Clinton, nonetheless) concluded that Gingrich did not violate any tax laws, leading renowned CNN Investigative Reporter Brooks Jackson to remark on air “it turns out [Gingrich] was right and those who accused him of tax fraud were wrong.” Transcript of CNN Report below: CNN INSIDE POLITICS 17:00 pm ET February 3, 1999 And up next: vindication at last? The Internal Revenue Service finally weighs in on the former speaker's college controversy. -

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Updated January 25, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL30857 Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Summary Each new House elects a Speaker by roll call vote when it first convenes. Customarily, the conference of each major party nominates a candidate whose name is placed in nomination. A Member normally votes for the candidate of his or her own party conference but may vote for any individual, whether nominated or not. To be elected, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of all the votes cast for individuals. This number may be less than a majority (now 218) of the full membership of the House because of vacancies, absentees, or Members answering “present.” This report provides data on elections of the Speaker in each Congress since 1913, when the House first reached its present size of 435 Members. During that period (63rd through 117th Congresses), a Speaker was elected six times with the votes of less than a majority of the full membership. If a Speaker dies or resigns during a Congress, the House immediately elects a new one. Five such elections occurred since 1913. In the earlier two cases, the House elected the new Speaker by resolution; in the more recent three, the body used the same procedure as at the outset of a Congress. If no candidate receives the requisite majority, the roll call is repeated until a Speaker is elected. Since 1913, this procedure has been necessary only in 1923, when nine ballots were required before a Speaker was elected. -

Charles Bartlett Interviewer: Fred Holborn Date of Interview: January 6, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C

Charles Bartlett Oral History Interview – JFK #1, 1/6/1965 Administrative Information Creator: Charles Bartlett Interviewer: Fred Holborn Date of Interview: January 6, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C. Length: 91 pp. Biographical Note Bartlett, Washington correspondent for the Chattanooga Times from 1948 to 1962, columnist for the Chicago Daily News, and personal friend of John F. Kennedy (JFK), discusses his role in introducing Jacqueline Bouvier to JFK, JFK’s relationship with Lyndon Baines Johnson, and JFK’s Cabinet appointments, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed October 11, 1983, copyright of these materials has been assigned to United States Government. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. Direct your questions concerning copyright to the reference staff. -

Today in Georgia History November 6, 1998 Newt Gingrich Suggested Reading “Newt Gingrich (B. 1943).” New Georgia Encyclope

Today in Georgia History November 6, 1998 Newt Gingrich Suggested Reading “Newt Gingrich (b. 1943).” New Georgia Encyclopedia. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-1384&sug=y “Newt Gingrich Biography.” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=G000225 “The Long March of Newt Gingrich,” PBS, Frontline. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/newt/ Amy D. Bernstein and Peter W. Bernstein, eds., Quotations from Speaker Newt: The Little Red, White, and Blue Book of the Republican Revolution (New York: Workman Publishing, 1995). Elizabeth Drew, Showdown: The Struggle between the Gingrich Congress and the Clinton White House (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996). Steven M. Gillon, The Pact: Bill Clinton, Newt Gingrich, and the Rivalry That Defined a Generation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008). Linda Killian, The Freshmen: What Happened to the Republican Revolution? (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1998). David Maraniss and Michael Weisskopf, Tell Newt to Shut Up!: Prizewinning Washington Post Journalists Reveal How Reality Gagged the Gingrich Revolution (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996). Mel Steely, The Gentleman from Georgia: The Biography of Newt Gingrich (Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 2000). Image Credits November 6, 1998: Newt Gingrich “Gingrich Gears Up For Possible New Position As Speaker Of House” November 9, 1994 Article courtesy of the Savannah Morning News, http://savannahnow.com/ “Republicans Bid for Congressional Control” November -

Chairman Rogers, Ranking Member Lowey, Members of the Committee

TESTIMONY OF REPRESENTATIVE JOSEPH P. KENNEDY, III (MA-04) SUBCOMMITTEE ON STATE, FOREIGN OPERATIONS AND RELATED PROGRAMS HOUSE APPROPRIATIONS MEMBER DAY HEARING MARCH 16, 2017 Chairman Rogers, Ranking Member Lowey, Members of the Committee: Thank you for convening this hearing today to discuss the resources that are vital for protecting America’s security, safeguarding our core values of democracy and human rights, and continuing America’s leadership across the world. As America and the world face unprecedented obstacles and instability, but also opportunities, your work has never been more important. Today I want to speak to you about the urgent need for an expanded Peace Corps. Some 7,200 Peace Corps Volunteers currently serve in 63 countries, training communities in critical areas of need, including food security, combating HIV/AIDS, and facilitating girls and women’s empowerment through education and economic independence. Through partnerships with PEPFAR, Feed the Future and the President’s Malaria Initiative, Volunteers provide crucial assistance to efforts to fight against HIV/AIDS, promote sustainable methods for food security, and eliminate malaria. The Peace Corps is also recognized for its indispensable role in national security. As 121 retired three and four-star generals recently wrote to Congressional leadership, “Peace Corps and other development agencies are critical to preventing conflict and reducing the need to put our men and women in uniform in harm’s way.” The Peace Corps’ cost-efficient, effective model is reflected -

Download on the AASL Website an Anonymous Funder Donated $170,000 Tee, and the Rainbow Round Table at Bit.Ly/AASL-Statements

May 2021 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION MARSHALL BREEDING’S LIBRARY SYSTEMS REPORTp. 22 Library Jobs Landscape p. 34 NEWSMAKER: Isabel Allende p. 20 PLUS: Drive-In Storytimes, Rural Telehealth, Bike Tour Librarian This Summer! Join us online at the event created and curated for the library community. Event Highlights • Educational programming • COVID-19 information for libraries • News You Can Use sessions highlighting • Interactive Discussion Groups new research and advances in libraries • Presidents' Programs • Memorable and inspiring featured authors • Livestreamed and on-demand sessions and celebrity speakers • Networking opportunities to share and The Library Marketplace with more than • connect with peers 250 exhibitors, Presentation Stages, Swag-A-Palooza, and more • Event content access for a full year ALA Members who have been recently furloughed, REGISTER TODAY laid o, or are experiencing a reduction of paid alaannual.org work hours are invited to register at no cost. #alaac21 Thank you to our Sponsors May 2021 American Libraries | Volume 52 #5 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 2021 LIBRARY SYSTEMS REPORT Advancing library technologies in challenging times | p. 22 BY Marshall Breeding FEATURES 38 JOBS REPORT 34 The Library Employment Landscape Job seekers navigate uncertain terrain BY Anne Ford 38 The Virtual Job Hunt Here’s how to stand out, both as an applicant and an employer BY Claire Zulkey 42 Serving the Community at All Times Cultural inclusivity programming during a pandemic BY Nicanor Diaz, Virginia Vassar -

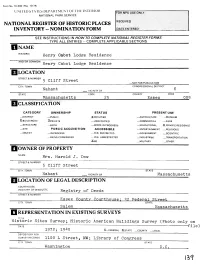

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATHS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Henry Cabot Lodge Residence AND/OR COMMON Henry Cabot Lodge Residence 5 Cliff Street .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Nahant VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Essex 009 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION -XNO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Harold J. Dow STREET & NUMBER 5 Cliff Street CITY, TOWN STATE Nahant VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Essex County Courthouse: ^2 Federal Street CITY, TOWN STATE Salem Massachusetts I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey; Historic American Buildings Survey (Photo only on DATE ————————————————————————————————————file) 1972; 19^0 X_FEDERAL 2LSTATE _COUNTY _J_OCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS 1100 L Street, NW; Library of Congress Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 3C ORIGINAL SITE X_QOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE This two-story, hip-roofed, white stucco-^covered, lavender- trimmed, brick villa is the only known extant residence associated with Henry Cabot Lodge.