The First Challenge Walking with Miskwaadesi the First Challenge THIRTEEN MOONS on a TURTLE’S BACK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACTS 44Th Annual Meeting and Symposium Tucson, Arizona February 21–23, 2019

ABSTRACTS 44th Annual Meeting and Symposium Tucson, Arizona February 21–23, 2019 FORTY-FOURTH ANNUAL MEETING AND SYMPOSIUM THE DESERT TORTOISE COUNCIL TUCSON, AZ February 21–23, 2019 ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS AND POSTERS (Abstracts arranged alphabetically by last name of first author) *Speaker, if not the first author listed Long-term Data Collection and Trends of a 130-Acre High Desert Riparian and Upland Preserve in Northwestern Mohave County, Arizona Julie Alpert and Robert Faught Willow Creek Environmental Consulting, LLC, 15857 E. Silver Springs Road, Kingman, Arizona 86401, USA.Phone: 928-692-6501. Email: [email protected] The Willow Creek Riparian Preserve (Preserve) is a privately owned 130-acre site located 30 miles east of Kingman, Arizona. The Preserve was formally established in 2007 with the purchase of 10-acres and an agreement with the eastern adjoining private landowner to add an additional 120-acres. The Preserve location was unfenced and wholly accessible by livestock, off-road vehicle use, and hunting. In October of 2008 the Preserve was fenced with volunteer efforts from the local Rotary Club and Boy Scout Troop 66. Additional financial assistance came through a large discount in the cost of fencing materials from Kingman Ace Hardware. A total of 0.5-linear mile of new wildlife friendly fencing (barbless top wire and 18-inches above-ground bottom wire) was installed along the south and west sides and connected to existing Arizona State Lands cattle allotment fencing. Baseline and on-going studies and data collection have occurred since 2004. These have included small mammal live trapping; chiropteran surveys with the use of Anabat; migratory, breeding, and winter avian surveys; amphibian and reptile surveys; deployment of game cameras; animal track and sign identification and movement patterns; vegetation and plant surveys; and a wetland delineation. -

Sea Turtle Activity Book

Sea Turtle Adventures II The adventure continues... An Activity Book for All Ages Welcome to Sarasota County! The beautiful beaches and surrounding waters of Sarasota REMOVE OBSTACLES: Turtles can easily become trapped County provide critical habitat for important populations in beach furniture, recreational equipment, tents and of threatened and endangered sea turtles. We are honored toys, or fall into deep holes in the sand. You can provide that many sea turtles make Sarasota County their home a more natural and safe shoreline for the turtles to nest year-round, while other sea turtles migrate to our beaches by removing all items from the beach each night. Also, from hundreds of miles away to find mates and nest. remember to leave the beach as you found it by knocking down sandcastles, filling in holes, and picking up garbage, Each year between May 1 and Oct. 31, adult female sea especially plastics, which can be mistaken for food by turtles crawl out of the Gulf of Mexico to lay approximately sea turtles. 100 eggs in a sandy nest on our beaches. The clutch incubates for almost two months until the hatchlings We hope you enjoy learning more about sea turtles in this emerge one night and make their way to the Gulf. During activity book. Thank you for sharing the shore and helping this special time of year, there are many things you can do to make our beaches more turtle-friendly! to help and protect these magnificent animals. Sincerely, LIMIT LIGHTING: Lights on the beach confuse and disorient Your Friends at Sarasota County sea turtles. -

Loggerhead Sea Turtle

Loggerhead Sea Turtle Description: The Loggerhead Sea Turtle is named for its large head and blunt jaw. This huge sea turtle can grow to 800 pounds (though the average turtle is about 200 pounds) and three and a half feet in length. It is the largest hard-shelled turtle in the world. The carapace (shell) and flippers are reddish brown and the plastron (lower shell) is yellowish. The carapace has five lateral scutes and five central scutes. Scutes are hexagonal sections of the carapace. Underparts are white or whitish. These incredible turtles have powerful flippers that can propel them through the water at speeds of up to 16 miles per hour. The Loggerhead Sea Turtle has a life span of up to 50 years in the wild. Habitat/Range: The seafaring Loggerhead Sea Turtle is found throughout the world's tropical oceans. They are also found in temperate waters in search of food and in migration. Breeding populations exist in many locales including the Atlantic coast of the United States (from North Carolina to Florida), numerous Caribbean islands, Central America, the Mediterranean Sea, and Africa. Diet: Loggerhead Sea Turtles consume fish, crustaceans, mollusks, crabs, and jellyfish, They use their powerful jaws to crush prey. These turtles often ingest stray plastic bags which are mistaken for jellyfish and which cause potentially fatal complications. Nesting: The Female Loggerhead Sea Turtle normally lays her eggs on the same beach in which she was born. It may take up to 30 years before these turtles reach reproductive age. In June or July, females will emerge from the ocean and dig a hole in the sand. -

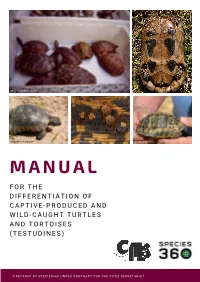

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

Eastern Snake-Necked Turtle

Husbandry Manual for Eastern Snake-Necked Turtle Chelodina longicollis Reptilia: Chelidae Image Courtesy of Jacki Salkeld Author: Brendan Mark Host Date of Preparation: 04/06/06 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE - Richmond Course Name and Number: 1068 Certificate 3 - Captive Animals Lecturers: Graeme Phipps/Andrew Titmuss/ Jacki Salkeld CONTENTS 1. Introduction 4 2. Taxonomy 5 2.1 Nomenclature 5 2.2 Subspecies 5 2.3 Synonyms 5 2.4 Other Common Names 5 3. Natural History 6 3.1 Morphometrics 6 3.1.1 Mass and Basic Body Measurements 6 3.1.2 Sexual Dimorphism 6 3.1.3 Distinguishing Features 7 3.2 Distribution and Habitat 7 3.3 Conservation Status 8 3.4 Diet in the Wild 8 3.5 Longevity 8 3.5.1 In the Wild 8 3.5.2 In Captivity 8 3.5.3 Techniques Used to Determine Age in Adults 9 4. Housing Requirements 10 4.1 Exhibit/Enclosure Design 10 4.2 Holding Area Design 10 4.3 Spatial Requirements 11 4.4 Position of Enclosures 11 4.5 Weather Protection 11 4.6 Temperature Requirements 12 4.7 Substrate 12 4.8 Nestboxes and/or Bedding Material 12 4.9 Enclosure Furnishings 12 5. General Husbandry 13 5.1 Hygiene and Cleaning 13 5.2 Record Keeping 13 5.3 Methods of Identification 13 5.4 Routine Data Collection 13 6. Feeding Requirements 14 6.1 Captive Diet 14 6.2 Supplements 15 6.3 Presentation of Food 15 1 7. Handling and Transport 16 7.1 Timing of Capture and Handling 16 7.2 Capture and Restraint Techniques 16 7.3 Weighing and Examination 17 7.4 Release 17 7.5 Transport Requirements 18 7.5.1 Box Design 18 7.5.2 Furnishings 19 7.5.3 Water and Food 19 7.5.4 Animals Per Box 19 7.5.5 Timing of Transportation 19 7.5.6 Release from Box 19 8. -

Sustainable Trade in Turtles and Tortoises

Action Plan for North America Sustainable Trade in Turtles and Tortoises Commission for Environmental Cooperation Please cite as: CEC. 2017. Sustainable Trade in Turtles and Tortoises: Action Plan for North America. Montreal, Canada: Commission for Environmental Cooperation. 60 pp. This report was prepared by Peter Paul van Dijk and Ernest W.T. Cooper, of E. Cooper Environmental Consulting, for the Secretariat of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC). The information contained herein is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the governments of Canada, Mexico or the United States of America. Reproduction of this document in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes may be made without special permission from the CEC Secretariat, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. The CEC would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication or material that uses this document as a source. Except where otherwise noted, this work is protected under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial–No Derivative Works License. © Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 2017 Publication Details Publication type: Project Publication Publication date: May 2017 Original language: English Review and quality assurance procedures: Final Party review: April 2017 QA313 Project: 2015-2016/Strengthening conservation and sustainable production of selected CITES Appendix II species in North America ISBN: 978-2-89700-208-4 (e-version); 978-2-89700-209-1 (print) Disponible en français -

Development of the Turtle Plastron, the Order-Defining Skeletal Structure

Development of the turtle plastron, the order-defining skeletal structure Ritva Ricea,1, Aki Kallonenb, Judith Cebra-Thomasc,d, and Scott F. Gilberta,c,1 aDevelopmental Biology, Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki 00014, Finland; bDepartment of Physics, University of Helsinki, Helsinki 00014, Finland; cDepartment of Biology, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA 19081; and dDepartment of Biology, Millersville University, Millersville, PA 17551 Edited by Clifford J. Tabin, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, and approved March 30, 2016 (received for review January 19, 2016) The dorsal and ventral aspects of the turtle shell, the carapace and the fontanel at the midline of the plastron. Moreover, processes extend plastron, are developmentally different entities. The carapace con- dorsally from the hyoplastron and hypoplastron to form a bridge that tains axial endochondral skeletal elements and exoskeletal dermal connects the plastron with the ribs and the carapace. In some turtles bones. The exoskeletal plastron is found in all extant and extinct (especially ancient lineages), a further set of paired plastron bones, species of crown turtles found to date and is synaptomorphic of the the mesoplastra, lie between the hyoplastra and hypoplastra (7). order Testudines. However, paleontological reconstructed transition Although the anatomy of plastron bones has been known for forms lack a fully developed carapace and show a progression of centuries, and the homology of these bones to the skeletal structures bony elements ancestral to the plastron. To understand the evolu- of other reptilian clades has been debated almost as long (3, 4, 6, 8), tionary development of the plastron, it is essential to know how it has we still know very little about how these intramembranous bones formed. -

Western Pond Turtle Shell Disease in Washington

Western Pond Turtle Shell Disease in Washington Background Western Pond Turtles (Figure 1) historically occurred in two regions in Washington: South Puget Sound and the Columbia Gorge. They were once locally common to abundant in South Puget Sound, but had become essentially extirpated from the region by the 1980s. Little is known about the history and sizes of populations in the Columbia Gorge, but only two populations remained by the mid- 1980s (Figure 2). The turtle was listed as endangered by the state of Washington in 1993. In 1994, the entire Washington population was estimated at about 156 turtles and occurred at two sites in the Columbia Gorge. Figure 1. Basking Western Pond Turtles, including marked animals with transmitters. Recovery Efforts A primary recovery strategy for Western Pond Turtles in Washington has been head-starting the turtles in a captive environment and then releasing them back into the wild at one of the six sites established for the recovery of this species. WDFW works with Woodland Park Zoo and Oregon Zoo to raise the turtles from the egg or hatchling stage (Figure 3) for approximately 9-10 months, when the accelerated growth rates result in turtles large enough to avoid predation when released back into the wild. The very successful 25-year old collaborative head-start program has helped reverse the fate of the Western Pond Turtle in Washington. More than 800 turtles now occur at six sites, well on their way Figure 2. Sondino Pond in Columbia River gorge – one of toward achieving recovery objectives. Wild turtles still persist at two last two known wild occurrences at the time of listing of the Columbia Gorge sites, but nearly all of the turtles in Washington were head-started. -

Amazing Adaptations

AMAZING ADAPTATIONS TIME & AUDIENCE LEVEL VOCABULARY Morphological adaptation All audiences Adaptation Nictitating Membrane Grades 2-5 Behavioral adaptation Plastron 30-35 Minutes Camouflage Rhamphotheca MATERIALS Carapace Salt Glands Loggerhead Epibiota Magnetite Crystals carapace Esophageal papillae Scute Loggerhead skull Hydrodynamic Flippers Rhamphotheca Keratin Esophageal papillae Knobbed Whelk OBJECTIVES Blue crab 1) Explain adaptation and differentiate between morphological and Epibiota carapace behavioral. Gopher tortoise shell 2) Identify morphological and behavioral adaptations in sea turtles. Kemp’s Ridley 3) Infer how each adaptation is advantageous to sea turtle survival. carapace/plastron SUMMARY Dress-up kit Adaptations are changes in the structure or function of an animal that allow it to survive in its environment. Sea turtles have many physical and behavioral adaptations that allow them to survive in their marine SET-UP environment. Arrange specimens on table in following order: Kemps PROGRAM carapace and plastron, gopher Sea turtles are marine reptiles that have a number of special tortoise shell, epibiota adaptations that allow them to live in a salt water environment. carapace, adult loggerhead Adaptations can be behavioral or morphological. A behavioral carapace, loggerhead skull adaptation is something a living organism does (ex: migration) as and rhamphotheca, knobbed opposed to a morphological adaptation which is a physical whelk and blue crab, characteristic an organism has developed (ex: esophageal papillae) for esophageal papillae survival. Place Word Wall words with Morphological Adaptations appropriate specimen The sea turtle’s carapace (top shell) and plastron (bottom shell) are Place dress-up items under hard and made of bone. The vertebrae and ribs are fused into the tablecloth. -

Carapace Bone Histology in the Giant Pleurodiran Turtle Stupendemys Geographicus: Phylogeny and Function

Carapace bone histology in the giant pleurodiran turtle Stupendemys geographicus: Phylogeny and function TORSTEN M. SCHEYER and MARCELO R. SÁNCHEZ−VILLAGRA Scheyer, T.M. and Sánchez−Villagra, M.R. 2007. Carapace bone histology in the giant pleurodiran turtle Stupendemys geographicus: Phylogeny and function. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 52 (1): 137–154. Stupendemys geographicus (Pleurodira: Pelomedusoides: Podocnemidae) is a giant turtle from the Miocene of Vene− zuela and Brazil. The bone histology of the carapace of two adult specimens from the Urumaco Formation is described herein, one of which is the largest of this species ever found. In order to determine phylogenetic versus scaling factors influencing bone histology, S. geographicus is compared with related podocnemid Podocnemis erythrocephala,and with fossil and Recent pelomedusoides taxa Bothremys barberi, Taphrosphys sulcatus,“Foxemys cf. F. mechinorum”, and Pelomedusa subrufa. Potential scaling effects on bone histology were further investigated by comparison to the Pleistocene giant tortoise Hesperotestudo (Caudochelys) crassiscutata and the Late Cretaceous marine protostegid turtle Archelon ischyros. A diploe structure of the shell with well developed external and internal cortices framing inte− rior cancellous bone is plesiomorphic for all sampled taxa. Similarly, the occurrence of growth marks in the shell ele− ments is interpreted as plesiomorphic, with the sampled neural elements providing the most extensive record of growth marks. The assignment of S. geographicus to the Podocnemidae was neither strengthened nor refuted by the bone his− tology. A reduced thickness of the internal cortex of the shell elements constitutes a potential synapomorphy of the Bothremydidae. S. geographicus and H. crassiscutata both express extensive weight−reduction through lightweight− construction while retaining form stability of the shell. -

Leatherback Sea Turtle Shell: a Tough and Flexible Biological Design

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/282130006 Leatherback Sea Turtle Shell: A Tough and Flexible Biological Design ARTICLE in ACTA BIOMATERIALIA · SEPTEMBER 2015 Impact Factor: 6.03 · DOI: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.09.023 CITATION READS 1 99 3 AUTHORS, INCLUDING: Wen Yang Marc A Meyers ETH Zurich University of California, San Diego 37 PUBLICATIONS 208 CITATIONS 484 PUBLICATIONS 11,198 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: Wen Yang letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 15 December 2015 Acta Biomaterialia xxx (2015) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Acta Biomaterialia journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/actabiomat Leatherback sea turtle shell: A tough and flexible biological design ⇑ Irene H. Chen a, Wen Yang a, Marc A. Meyers a,b, a Materials Science and Engineering Program, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA b Departments of Nanoengineering and Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA article info abstract Article history: The leatherback sea turtle is unique among chelonians for having a soft skin which covers its osteoderms. Received 9 March 2015 The osteoderm is composed of bony plates that are interconnected with collagen fibers in a structure Received in revised form 19 August 2015 called suture. The soft dermis and suture geometry enable a significant amount of flexing of the junction Accepted 17 September 2015 between adjacent osteoderms. This design allows the body to contract better than a hard-shelled sea tur- Available online xxxx tle as it dives to depths of over 1000 m. -

Testudines, Chelidae

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.06013 Original Article Underwater turning movement during foraging in Hydromedusa maximiliani (Testudines, Chelidae) from southeastern Brazil Rocha-Barbosa, O.a*, Hohl, LSL.a, Novelli, IA.b,c, Sousa, BM.b, Gomides, SC.b and Loguercio, MFC.a aLAZOVERTE – Laboratório de Zoologia de Vertebrados - Tetrapoda, Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologia Roberto Alcantara Gomes – IBRAG, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro – UERJ, Rua São Francisco Xavier, 524, Maracanã, CEP 20550-013, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil bLaboratório de Herpetologia, Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora – UFJF, Rua José Lourenço Kelmer, s/n, Campus Universitário, São Pedro, CEP 36036-900, Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil cPrograma de Pós-graduação em Ciências Biológicas, Comportamento e Biologia Animal, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora – UFJF, Rua José Lourenço Kelmer, Martelos, CEP 36036-330, Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected] Received: April 23, 2013 – Accepted: August 13, 2013 – Distributed: December 31, 2014 (With 4 figures) Abstract A type of locomotor behavior observed in animals with rigid bodies, that can be found in many animals with exoskeletons, shells, or other forms of body armor, to change direction, is the turning behavior. Aquatic floated-turning behavior among rigid bodies animals have been studied in whirligig beetles, boxfish, and more recently in freshwater turtle, Chrysemys picta. In the laboratory we observed a different kind of turning movement that consists in an underwater turning movement during foraging, wherein the animal pivoted its body, using one of the hindlimbs as the fixed-point support in the substratum.