One in a Thousand: Those Amazing Sea Turtles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACTS 44Th Annual Meeting and Symposium Tucson, Arizona February 21–23, 2019

ABSTRACTS 44th Annual Meeting and Symposium Tucson, Arizona February 21–23, 2019 FORTY-FOURTH ANNUAL MEETING AND SYMPOSIUM THE DESERT TORTOISE COUNCIL TUCSON, AZ February 21–23, 2019 ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS AND POSTERS (Abstracts arranged alphabetically by last name of first author) *Speaker, if not the first author listed Long-term Data Collection and Trends of a 130-Acre High Desert Riparian and Upland Preserve in Northwestern Mohave County, Arizona Julie Alpert and Robert Faught Willow Creek Environmental Consulting, LLC, 15857 E. Silver Springs Road, Kingman, Arizona 86401, USA.Phone: 928-692-6501. Email: [email protected] The Willow Creek Riparian Preserve (Preserve) is a privately owned 130-acre site located 30 miles east of Kingman, Arizona. The Preserve was formally established in 2007 with the purchase of 10-acres and an agreement with the eastern adjoining private landowner to add an additional 120-acres. The Preserve location was unfenced and wholly accessible by livestock, off-road vehicle use, and hunting. In October of 2008 the Preserve was fenced with volunteer efforts from the local Rotary Club and Boy Scout Troop 66. Additional financial assistance came through a large discount in the cost of fencing materials from Kingman Ace Hardware. A total of 0.5-linear mile of new wildlife friendly fencing (barbless top wire and 18-inches above-ground bottom wire) was installed along the south and west sides and connected to existing Arizona State Lands cattle allotment fencing. Baseline and on-going studies and data collection have occurred since 2004. These have included small mammal live trapping; chiropteran surveys with the use of Anabat; migratory, breeding, and winter avian surveys; amphibian and reptile surveys; deployment of game cameras; animal track and sign identification and movement patterns; vegetation and plant surveys; and a wetland delineation. -

Sea Turtle Activity Book

Sea Turtle Adventures II The adventure continues... An Activity Book for All Ages Welcome to Sarasota County! The beautiful beaches and surrounding waters of Sarasota REMOVE OBSTACLES: Turtles can easily become trapped County provide critical habitat for important populations in beach furniture, recreational equipment, tents and of threatened and endangered sea turtles. We are honored toys, or fall into deep holes in the sand. You can provide that many sea turtles make Sarasota County their home a more natural and safe shoreline for the turtles to nest year-round, while other sea turtles migrate to our beaches by removing all items from the beach each night. Also, from hundreds of miles away to find mates and nest. remember to leave the beach as you found it by knocking down sandcastles, filling in holes, and picking up garbage, Each year between May 1 and Oct. 31, adult female sea especially plastics, which can be mistaken for food by turtles crawl out of the Gulf of Mexico to lay approximately sea turtles. 100 eggs in a sandy nest on our beaches. The clutch incubates for almost two months until the hatchlings We hope you enjoy learning more about sea turtles in this emerge one night and make their way to the Gulf. During activity book. Thank you for sharing the shore and helping this special time of year, there are many things you can do to make our beaches more turtle-friendly! to help and protect these magnificent animals. Sincerely, LIMIT LIGHTING: Lights on the beach confuse and disorient Your Friends at Sarasota County sea turtles. -

La Terre Ne Nous Appartient Pas, Ce Sont Nos Enfants Qui Nous La Prêtent”

Réserve Naturelle Nationale de Saint-Martin Le Journal “La terre ne nous appartient pas, ce sont nos enfants qui nous la prêtent” Trimestriel n°29 juillet 2017 Sommaire Megara 2017 : troisième édition: 4/5 Megara 2017: Mission #3 Un atelier en faveur des récifs et 6 A workshop In Support of Reefs des herbiers and Plant Beds Une thèse en faveur des herbiers 7 A Thesis About Plant Beds Un plan structuré contre la 8 A Solid Plan To Fight Hydrocarbon pollution aux hydrocarbures Pollution Des données conservées 9 Conserving Data Forever and Ever Des échasses clandestines 10 Clandestine Birds Nesting Sauvetage d’une tortue fléchée 11 Saving An Injured Turtle Un filet au Galion 12 Fishnet at Galion Saisie d’un filet de 300 mètres 12 300-meter Fishnet Seized Double saisie pour deux pêcheurs 13 Double Trouble For Two Fishermen Quads dans la Réserve 14 Quads in the Réserve: Poisson-lion et ciguatera 15 Lionfish and Ciguatera: Le centre équestre déménagera 16 Galion Equestrian Center To Move 17 bouées de mouillage à Tintamare 17 17 Buoys at Tintamare De nouveaux panneaux, interactifs 18 New Interactive Signage Bye bye Romain Renoux ! 19 Bye bye Romain Renoux! Toutes les réserves en Martinique 20/21 Nature Reserves Met In Martinique Cours de SVT à Pinel 22 Science Classes at Pinel Des régatiers et des baleines 23 Regattas VS Whales Un nouveau parc marin. Bravo Aruba ! 24/25 A New Marine Park. Bravo Aruba! Le Forum UE-PTOM à Aruba 26 UE-PTOM Forum in Aruba BEST : 2 beaux projets à Anguilla 27/30 BEST: 2 Winning Projects in Anguilla Réunion sur les baleines à bosse 31/32 Metting about Humpback Whales BEST : dernier appel à projets 32/33 BEST: Last Call For Projects 2 Edito à nos visiteurs des sites préservés, des plages propres, des eaux de baignade de qualité, ils ne viendront plus ! Le maintien de notre biodiversi- té et la préservation des différents écosystèmes marins et terrestres à Saint Martin sont une pri- orité. -

Green Sea Turtle in the New England Aquarium Has Been in Captivity Since 1970, and Is Believed to Be Around 80 Years Old (NEAQ 2013)

Species Status Assessment Class: Reptilia Family: Cheloniidae Scientific Name: Chelonia mydas Common Name: Green turtle Species synopsis: The green turtle is a marine turtle that was originally described by Linnaeus in 1758 as Testudo mydas. In 1868 Marie Firmin Bocourt named a new species of sea turtle Chelonia agassizii. It was later determined that these represented the same species, and the name became Chelonia mydas. In New York, the green turtle can be found from July – November, with individuals occasionally found cold-stunned in the winter months (Berry et al. 1997, Morreale and Standora 1998). Green turtles are sighted most frequently in association with sea grass beds off the eastern side of Long Island. They are observed with some regularity in the Peconic Estuary (Morreale and Standora 1998). Green turtles experienced a drastic decline throughout their range during the 19th and 20th centuries as a result of human exploitation and anthropogenic habitat degradation (NMFS and USFWS 1991). In recent years, some populations, including the Florida nesting population, have been experiencing some signs of increase (NMFS and USFWS 2007). Trends have not been analyzed in New York; a mark-recapture study performed in the state from 1987 – 1992 found that there seemed to be more green turtles at the end of the study period (Berry et al. 1997). However, changes in temperature have lead to an increase in the number of cold stunned green turtles in recent years (NMFS, Riverhead Foundation). Also, this year a record number of nests were observed at nesting beaches in Flordia (Mote Marine Laboratory 2013). 1 I. -

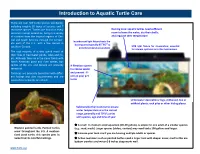

Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care

Mississippi Map Turtle Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care There are over 300 turtle species worldwide, including roughly 60 types of tortoise and 7 sea turtle species. Turtles are found on every Basking area: aquatic turtles need sufficient continent except Antarctica, living in a variety room to leave the water, dry their shells, of climates from the tropical regions of Cen- and regulate their temperature. tral and South America through the temper- Incandescent light fixture heats the ate parts of the U.S., with a few species in o- o) basking area (typically 85 95 to UVB light fixture for illumination; essential southern Canada. provide temperature gradient for vitamin synthesis in turtles held indoors The vast majority of turtles spend much of their lives in freshwater ponds, lakes and riv- ers. Although they are in the same family with North American pond and river turtles, box turtles of the U.S. and Mexico are primarily A filtration system terrestrial. to remove waste Tortoises are primarily terrestrial with differ- and prevent ill- ent habitat and diet requirements and are ness in your pet covered in a separate care sheet. turtle Underwater decorations: logs, driftwood, live or artificial plants, rock piles or other hiding places. Submersible thermometer to ensure water temperature is in the correct range, generally mid 70osF; varies with species, age and time of year A small to medium-sized aquarium (20-29 gallons) is ample for one adult of a smaller species Western painted turtle. Painted turtles (e.g., mud, musk). Larger species (sliders, cooters) may need tanks 100 gallons and larger. -

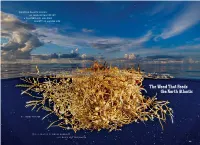

The Weed That Feeds the North Atlantic

DRIFTING PLANTS KNOWN AS SARGASSUM SUPPORT A COMPLEX AND AMAZING VARIETY OF MARINE LIFE. The Weed That Feeds the North Atlantic BY JAMES PROSEK PHOTOGRAPHS BY DAVID DOUBILET AND DAVID LIITTSCHWAGER 129 Hatchling sea turtles, like this juvenile log- gerhead, make their way from the sandy beaches where they were born toward mats of sargassum weed, finding food and refuge from predators during their first years of life. PREVIOUS PHOTO A clump of sargassum weed the size of a soccer ball drifts near Bermuda in the slow swirl of the Sargasso Sea, part of the North Atlantic gyre. A weed mass this small may shelter thousands of organisms, from larval fish to seahorses. DAVID DOUBILET (BOTH) 130 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC THE WEED THAT FEEDS THE NORTH ATLANTIC 131 ‘There’s nothing like it in any other ocean,’ says marine biologist Brian Lapointe. ‘There’s nowhere else on our blue planet that supports such diversity in the middle of the ocean—and it’s because of the weed.’ LAPOINTE IS TALKING about a floating seaweed known as sargassum in a region of the Atlantic called the Sargasso Sea. The boundaries of this sea are vague, defined not by landmasses but by five major currents that swirl in a clockwise embrace around Bermuda. Far from any main- land, its waters are nutrient poor and therefore exceptionally clear and stunningly blue. The Sargasso Sea, part of the vast whirlpool known as the North Atlantic gyre, often has been described as an oceanic desert—and it would appear to be, if it weren’t for the floating mats of sargassum. -

Threats to Sea Turtles Artificial Lighting

Threats to Sea Turtles Artificial Lighting Artificial lighting is a significant sea turtle conservation problem. Sea turtle hatchlings instinctively move towards the brightest light when they hatch – on a natural beach, this is the night sky over the ocean. The artificial lighting causes the hatchlings to become disoriented, and ultimately leads to their death. Below are two maps. The “Artificial Lighting” map is a satellite image of the lights that are visible at night in Florida from space. The “Florida County” map will be used for reference. You will also need your “Sea Turtle Nesting Data” from an earlier lesson. Directions: Using the data provided identify areas where artificial lighting has the greatest impact on sea turtle hatchlings. Artificial Lighting Map Lightly shaded areas (yellow) - Lights visible at night from space Compare the “Artificial Lighting” map with the blank county map below. Color in the counties which have the most visible night lights from space. County Map Compare this data with data you collected earlier of the nesting sites of Green, Leatherback and Loggerhead turtles. Green Nesting Map Leatherback Nesting Map Loggerhead Nesting Map Questions 1. Describe the relationship between the nesting data and the artificial lighting data. ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ -

Spirorchiidiasis in Stranded Loggerhead Caretta Caretta and Green Turtles Chelonia Mydas in Florida (USA): Host Pathology and Significance

Vol. 89: 237–259, 2010 DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Published April 12 doi: 10.3354/dao02195 Dis Aquat Org OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Spirorchiidiasis in stranded loggerhead Caretta caretta and green turtles Chelonia mydas in Florida (USA): host pathology and significance Brian A. Stacy1,*, Allen M. Foley2, Ellis Greiner3, Lawrence H. Herbst4, Alan Bolten5, Paul Klein6, Charles A. Manire7, Elliott R. Jacobson1 1University of Florida, College of Veterinary Medicine, Large Animal Clinical Sciences, PO Box 100136, Gainesville, Florida 32610, USA 2Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Jacksonville Field Laboratory, 370 Zoo Parkway, Jacksonville, Florida 32221, USA 3University of Florida, College of Veterinary Medicine, Infectious Diseases and Pathology, PO Box 110880, Gainesville, Florida 32610, USA 4Department of Pathology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York 10461, USA 5Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research, University of Florida, PO Box 118525, Gainesville, Florida 32611, USA 6Department of Pathology, Immunology, and Laboratory Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32610, USA 7Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, 1600 Ken Thompson Parkway, Sarasota, Florida 34236, USA ABSTRACT: Spirorchiid trematodes are implicated as an important cause of stranding and mortality in sea turtles worldwide. However, the impact of these parasites on sea turtle health is poorly understood due to biases in study populations and limited or missing data for some host species and regions, includ- ing the southeastern United States. We examined necropsy findings and parasitological data from 89 log- gerhead Caretta caretta and 59 green turtles Chelonia mydas that were found dead or moribund (i.e. stranded) in Florida (USA) and evaluated the role of spirorchiidiasis in the cause of death. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

A Divergence Dating Analysis of Turtles Using Fossil Calibrations: an Example of Best Practices Walter G

Journal of Paleontology, 87(4), 2013, p. 612–634 Copyright Ó 2013, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/13/0087-612$03.00 DOI: 10.1666/12-149 A DIVERGENCE DATING ANALYSIS OF TURTLES USING FOSSIL CALIBRATIONS: AN EXAMPLE OF BEST PRACTICES WALTER G. JOYCE,1,2 JAMES F. PARHAM,3 TYLER R. LYSON,2,4,5 RACHEL C. M. WARNOCK,6,7 7 AND PHILIP C. J. DONOGHUE 1Institut fu¨r Geowissenschaften, University of Tu¨bingen, 72076 Tu¨bingen, Germany, ,[email protected].; 2Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, New Haven, CT 06511, USA; 3John D. Cooper Archaeological and Paleontological Center, Department of Geological Sciences, California State University at Fullerton, Fullerton, CA 92834, USA; 4Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20013, USA; 5Marmarth Research Foundation, Marmarth, ND 58643, USA; 6National Evolutionary Synthesis Center, Durham, NC 27705, USA; and 7Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK ABSTRACT—Turtles have served as a model system for molecular divergence dating studies using fossil calibrations. However, because some parts of the fossil record of turtles are very well known, divergence age estimates from molecular phylogenies often do not differ greatly from those observed directly from the fossil record alone. Also, the phylogenetic position and age of turtle fossil calibrations used in previous studies have not been adequately justified. We provide the first explicitly justified minimum and soft maximum age constraints on 22 clades of turtles following best practice protocols. Using these data we undertook a Bayesian relaxed molecular clock analysis establishing a timescale for the evolution of crown Testudines that we exploit in attempting to address evolutionary questions that cannot be resolved with fossils alone. -

Pelagic Sargassum Community Change Over a 40-Year Period: Temporal and Spatial Variability

Mar Biol (2014) 161:2735–2751 DOI 10.1007/s00227-014-2539-y ORIGINAL PAPER Pelagic Sargassum community change over a 40-year period: temporal and spatial variability C. L. Huffard · S. von Thun · A. D. Sherman · K. Sealey · K. L. Smith Jr. Received: 20 May 2014 / Accepted: 3 September 2014 / Published online: 14 September 2014 © The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Pelagic forms of the brown algae (Phaeo- ranging across the Sargasso Sea, Gulf Stream, and south phyceae) Sargassum spp. and their conspicuous rafts are of the subtropical convergence zone. Recent samples also defining characteristics of the Sargasso Sea in the western recorded low coverage by sessile epibionts, both calcifying North Atlantic. Given rising temperatures and acidity in forms and hydroids. The diversity and species composi- the surface ocean, we hypothesized that macrofauna asso- tion of macrofauna communities associated with Sargas- ciated with Sargassum in the Sargasso Sea have changed sum might be inherently unstable. While several biological with respect to species composition, diversity, evenness, and oceanographic factors might have contributed to these and sessile epibiota coverage since studies were con- observations, including a decline in pH, increase in sum- ducted 40 years ago. Sargassum communities were sam- mer temperatures, and changes in the abundance and distri- pled along a transect through the Sargasso Sea in 2011 and bution of Sargassum seaweed in the area, it is not currently 2012 and compared to samples collected in the Sargasso possible to attribute direct causal links. Sea, Gulf Stream, and south of the subtropical conver- gence zone from 1966 to 1975. -

Flatback Turtles Along the Stunning Coastline of Western Australia

PPRROOJJEECCTT RREEPPOORRTT Expedition dates: 8 – 22 November 2010 Report published: October 2011 Beach combing for conservation: monitoring flatback turtles along the stunning coastline of Western Australia. 0 BEST BEST FOR TOP BEST WILDLIFE BEST IN ENVIRONMENT TOP HOLIDAY © Biosphere Expeditions VOLUNTEERING GREEN-MINDED RESPONSIBLE www.biosphereVOLUNTEERING-expeditions.orgSUSTAINABLE AWARD FOR NATURE ORGANISATION TRAVELLERS HOLIDAY HOLIDAY TRAVEL Germany Germany UK UK UK UK USA EXPEDITION REPORT Beach combing for conservation: monitoring flatback turtles along the stunning coastline of Western Australia. Expedition dates: 8 - 22 November 2010 Report published: October 2011 Authors: Glenn McFarlane Conservation Volunteers Australia Matthias Hammer (editor) Biosphere Expeditions This report is an adaptation of “Report of 2010 nesting activity for the flatback turtle (Natator depressus) at Eco Beach Wilderness Retreat, Western Australia” by Glenn McFarlane, ISBN: 978-0-9807857-3-9, © Conservation Volunteers. Glenn McFarlane’s report is reproduced with minor adaptations in the abstract and chapter 2; the remainder is Biosphere Expeditions’ work. All photographs in this report are Glenn McFarlane’s copyright unless otherwise stated. 1 © Biosphere Expeditions www.biosphere-expeditions.org Abstract The nesting population of Australian flatback (Natator depressus) sea turtles at Eco Beach, Western Australia, continues to be the focus of this annual programme, which resumes gathering valuable data on the species, dynamic changes to the nesting environment and a strong base for environmental teaching and training of all programme participants. Whilst the Eco Beach population is not as high in density as other Western Australian nesting populations at Cape Domett, Barrow Island or the Pilbara region, it remains significant for the following reasons: The 12 km nesting beach and survey area is free from human development, which can impact on nesting turtles and hatchlings.