Sustainable Trade in Turtles and Tortoises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACTS 44Th Annual Meeting and Symposium Tucson, Arizona February 21–23, 2019

ABSTRACTS 44th Annual Meeting and Symposium Tucson, Arizona February 21–23, 2019 FORTY-FOURTH ANNUAL MEETING AND SYMPOSIUM THE DESERT TORTOISE COUNCIL TUCSON, AZ February 21–23, 2019 ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS AND POSTERS (Abstracts arranged alphabetically by last name of first author) *Speaker, if not the first author listed Long-term Data Collection and Trends of a 130-Acre High Desert Riparian and Upland Preserve in Northwestern Mohave County, Arizona Julie Alpert and Robert Faught Willow Creek Environmental Consulting, LLC, 15857 E. Silver Springs Road, Kingman, Arizona 86401, USA.Phone: 928-692-6501. Email: [email protected] The Willow Creek Riparian Preserve (Preserve) is a privately owned 130-acre site located 30 miles east of Kingman, Arizona. The Preserve was formally established in 2007 with the purchase of 10-acres and an agreement with the eastern adjoining private landowner to add an additional 120-acres. The Preserve location was unfenced and wholly accessible by livestock, off-road vehicle use, and hunting. In October of 2008 the Preserve was fenced with volunteer efforts from the local Rotary Club and Boy Scout Troop 66. Additional financial assistance came through a large discount in the cost of fencing materials from Kingman Ace Hardware. A total of 0.5-linear mile of new wildlife friendly fencing (barbless top wire and 18-inches above-ground bottom wire) was installed along the south and west sides and connected to existing Arizona State Lands cattle allotment fencing. Baseline and on-going studies and data collection have occurred since 2004. These have included small mammal live trapping; chiropteran surveys with the use of Anabat; migratory, breeding, and winter avian surveys; amphibian and reptile surveys; deployment of game cameras; animal track and sign identification and movement patterns; vegetation and plant surveys; and a wetland delineation. -

Sea Turtle Activity Book

Sea Turtle Adventures II The adventure continues... An Activity Book for All Ages Welcome to Sarasota County! The beautiful beaches and surrounding waters of Sarasota REMOVE OBSTACLES: Turtles can easily become trapped County provide critical habitat for important populations in beach furniture, recreational equipment, tents and of threatened and endangered sea turtles. We are honored toys, or fall into deep holes in the sand. You can provide that many sea turtles make Sarasota County their home a more natural and safe shoreline for the turtles to nest year-round, while other sea turtles migrate to our beaches by removing all items from the beach each night. Also, from hundreds of miles away to find mates and nest. remember to leave the beach as you found it by knocking down sandcastles, filling in holes, and picking up garbage, Each year between May 1 and Oct. 31, adult female sea especially plastics, which can be mistaken for food by turtles crawl out of the Gulf of Mexico to lay approximately sea turtles. 100 eggs in a sandy nest on our beaches. The clutch incubates for almost two months until the hatchlings We hope you enjoy learning more about sea turtles in this emerge one night and make their way to the Gulf. During activity book. Thank you for sharing the shore and helping this special time of year, there are many things you can do to make our beaches more turtle-friendly! to help and protect these magnificent animals. Sincerely, LIMIT LIGHTING: Lights on the beach confuse and disorient Your Friends at Sarasota County sea turtles. -

§4-71-6.5 LIST of CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November

§4-71-6.5 LIST OF CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November 28, 2006 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Plesiopora FAMILY Tubificidae Tubifex (all species in genus) worm, tubifex PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Crustacea ORDER Anostraca FAMILY Artemiidae Artemia (all species in genus) shrimp, brine ORDER Cladocera FAMILY Daphnidae Daphnia (all species in genus) flea, water ORDER Decapoda FAMILY Atelecyclidae Erimacrus isenbeckii crab, horsehair FAMILY Cancridae Cancer antennarius crab, California rock Cancer anthonyi crab, yellowstone Cancer borealis crab, Jonah Cancer magister crab, dungeness Cancer productus crab, rock (red) FAMILY Geryonidae Geryon affinis crab, golden FAMILY Lithodidae Paralithodes camtschatica crab, Alaskan king FAMILY Majidae Chionocetes bairdi crab, snow Chionocetes opilio crab, snow 1 CONDITIONAL ANIMAL LIST §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Chionocetes tanneri crab, snow FAMILY Nephropidae Homarus (all species in genus) lobster, true FAMILY Palaemonidae Macrobrachium lar shrimp, freshwater Macrobrachium rosenbergi prawn, giant long-legged FAMILY Palinuridae Jasus (all species in genus) crayfish, saltwater; lobster Panulirus argus lobster, Atlantic spiny Panulirus longipes femoristriga crayfish, saltwater Panulirus pencillatus lobster, spiny FAMILY Portunidae Callinectes sapidus crab, blue Scylla serrata crab, Samoan; serrate, swimming FAMILY Raninidae Ranina ranina crab, spanner; red frog, Hawaiian CLASS Insecta ORDER Coleoptera FAMILY Tenebrionidae Tenebrio molitor mealworm, -

Loggerhead Sea Turtle

Loggerhead Sea Turtle Description: The Loggerhead Sea Turtle is named for its large head and blunt jaw. This huge sea turtle can grow to 800 pounds (though the average turtle is about 200 pounds) and three and a half feet in length. It is the largest hard-shelled turtle in the world. The carapace (shell) and flippers are reddish brown and the plastron (lower shell) is yellowish. The carapace has five lateral scutes and five central scutes. Scutes are hexagonal sections of the carapace. Underparts are white or whitish. These incredible turtles have powerful flippers that can propel them through the water at speeds of up to 16 miles per hour. The Loggerhead Sea Turtle has a life span of up to 50 years in the wild. Habitat/Range: The seafaring Loggerhead Sea Turtle is found throughout the world's tropical oceans. They are also found in temperate waters in search of food and in migration. Breeding populations exist in many locales including the Atlantic coast of the United States (from North Carolina to Florida), numerous Caribbean islands, Central America, the Mediterranean Sea, and Africa. Diet: Loggerhead Sea Turtles consume fish, crustaceans, mollusks, crabs, and jellyfish, They use their powerful jaws to crush prey. These turtles often ingest stray plastic bags which are mistaken for jellyfish and which cause potentially fatal complications. Nesting: The Female Loggerhead Sea Turtle normally lays her eggs on the same beach in which she was born. It may take up to 30 years before these turtles reach reproductive age. In June or July, females will emerge from the ocean and dig a hole in the sand. -

Texas Tortoise

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE TEXAS TORTOISE, CONTACT: ∙ TPWD: 800-792-1112 OF THE FOUR SPECIES OF TORTOISES FOUND http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/ IN NORTH AMERICA, THE TEXAS TORTOISE TEXAS ∙ Gulf Coast Turtle and Tortoise Society: IS THE ONLY ONE FOUND IN TEXAS. 866-994-2887 http://www.gctts.org/ THE TEXAS TORTOISE CAN BE FOUND IF YOU FIND A TEXAS TORTOISE THROUGHOUT SOUTHERN TEXAS AS WELL AS (OUT OF HABITAT), CONTACT: TORTOISE ∙ TPWD Law Enforcement TORTOISE NORTHEASTERN MEXICO. ∙ Permitted rehabbers in your area http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/huntwild/wild/rehab/ GOPHERUS BERLANDIERI UNFORTUNATELY EVERYTHING THERE ARE MANY THREATS YOU NEED TO KNOW TO THE SURVIVAL OF THE ABOUT THE STATE’S ONLY TEXAS TORTOISE: NATIVE TORTOISE HABITAT LOSS | ILLEGAL COLLECTION & THE THREATS IT FACES ROADSIDE MORTALITIES | PREDATION EXOTIC PATHOGENS TexasTortoise_brochure_V3.indd 1 3/28/12 12:12 PM COUNTIES WHERE THE TEXAS TORTOISE IS LISTED THE TEXAS TORTOISE (Gopherus berlandieri) is the smallest of the North American tortoises, reaching a shell length of about TEXAS TORTOISE AS A THREATENED SPECIES 8½ inches (22cm). The Texas tortoise can be distinguished CAN BE FOUND IN THE STATE OF TEXAS AND THEREFORE from other turtles found in Texas by its cylindrical and IS PROTECTED BY STATE LAW. columnar hind legs and by the yellow-orange scutes (plates) on its carapace (upper shell). IT IS ILLEGAL TO COLLECT, POSSESS, OR HARM A TEXAS TORTOISE. PENALTIES CAN INCLUDE PAYING A FINE OF Aransas, Atascosa, Bee, Bexar, Brewster, $273.50 PER TORTOISE. Brooks, Calhoun, Cameron, De Witt, Dimmit, Duval, Edwards, Frio, Goliad, Gonzales, Guadalupe, Hidalgo, Jackson, Jim Hogg, Jim Wells, Karnes, Kenedy, Kinney, Kleberg, La Salle, Lavaca, Live Oak, Matagorda, Maverick, McMullen, Medina, Nueces, WHAT SHOULD YOU Refugio, San Patricio, Starr, Sutton, Terrell, Uvalde, Val Verde, Victoria, Webb, Willacy, DO IF YOU FIND A Wilson, Zapata, Zavala TEXAS TORTOISE? THE TEXAS TORTOISE IS THE SMALLEST IN THE WILD AN INDIVIDUAL TEXAS TORTOISE LEAVE IT ALONE. -

Buffelgrass and Sonoran Desert Tortoises

National Park Service Resource Brief U.S. Department of the Interior Saguaro National Park Resource Management Division Effects of Buffelgrass on Sonoran Desert Tortoises 0.72 Introduction Females Males Invasions by nonnative species threaten biodiversity 0.68 ± SE) ± worldwide and can alter the structure and process of 3 sensitive ecosystems. Buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare), a perennial bunchgrass native to northern Africa and 0.64 Asia, was introduced to the southwestern U.S. in the 1930s and has invaded southwestern deserts. It creates 0.60 a dense grass layer where the ground cover was his- Condition (g/cm torically sparse. Buffelgrass can exclude native plants 0.56 and eliminate species that provide food and cover 0 5 10 15 20 for native herbivores (animals that eat only plants). Buffelgrass(%) In addition, areas invaded by buffelgrass have much higher biomass than native deserts, which increases the frequency and intensity of fires. Figure 1. Average condition of adult tortoises across a gradient of buffelgrass cover Sonoran desert tortoises (Gopherus morafkai) occur throughout southern Arizona and northern Mexico, plot, with a range of 0-12 tortoises per plot. In total, a region where the distribution of buffelgrass has they located 155 individual tortoises, of which 131 were increased markedly in recent years. The changes in adults (62 females, 69 males) and 24 were juveniles. vegetation in areas invaded by buffelgrass have the The density of tortoises averaged 0.33 tortoises per potential to affect tortoises because buffelgrass reduc- hectare (1 hectare = 2.47 acres) and did not vary with es the distribution and abundance of their native plant the amount of buffelgrass cover. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

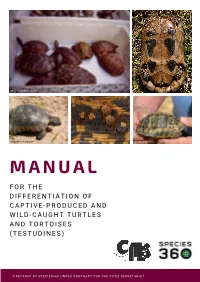

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

University of Nevada, Reno Effects of Fire on Desert Tortoise (Gopherus Agassizii) Thermal Ecology a Dissertation Submitted in P

University of Nevada, Reno Effects of fire on desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) thermal ecology A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology by Sarah J. Snyder Dr. C. Richard Tracy/Dissertation Advisor May 2014 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by SARAH J. SNYDER Entitled Effects of fire on desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) thermal ecology be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY C. Richard Tracy, Ph.D., Advisor Kenneth Nussear, Ph.D., Committee Member Peter Weisberg, Ph.D., Committee Member Lynn Zimmerman, Ph.D., Committee Member Lesley DeFalco, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2014 i ABSTRACT Among the many threats facing the desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) is the destruction and alteration of habitat. In recent years, wildfires have burned extensive portions of tortoise habitat in the Mojave Desert, leaving burned landscapes that are virtually devoid of living vegetation. Here, we investigated the effects of fire on the thermal ecology of the desert tortoise by quantifying the thermal quality of above- and below-ground habitat, determining which shrub species are most thermally valuable for tortoises including which shrub species are used by tortoises most frequently, and comparing the body temperature of tortoises in burned and unburned habitat. To address these questions we placed operative temperature models in microhabitats that received filtered radiation to test the validity of assuming that the interaction between radiation and radiation-absorbing properties of the model can result in a single, mean radiant absorptance regardless of whether the incident solar radiation is direct unfiltered or filtered by plant canopies, using the desert tortoise as a case study. -

Dermatemys Mawii (The Hicatee, Tortuga Blanca, Or Central American River Turtle): a Working Bibliography

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325206006 Dermatemys mawii (The Hicatee, Tortuga Blanca, or Central American River Turtle): A Working Bibliography Article · May 2018 CITATIONS READS 0 521 6 authors, including: Venetia Briggs Sergio C. Gonzalez University of Florida University of Florida 16 PUBLICATIONS 133 CITATIONS 9 PUBLICATIONS 39 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Thomas Rainwater Clemson University 143 PUBLICATIONS 1,827 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Crocodiles in the Everglades View project Dissertation: The role of habitat expansion on amphibian community structure View project All content following this page was uploaded by Sergio C. Gonzalez on 17 May 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 2018 Endangered and ThreatenedCaribbean Species Naturalist of the Caribbean Region Special Issue No. 2 V. Briggs-Gonzalez, S.C. Gonzalez, D. Smith, K. Allen, T.R. Rainwater, and F.J. Mazzotti 2018 CARIBBEAN NATURALIST Special Issue No. 2:1–22 Dermatemys mawii (The Hicatee, Tortuga Blanca, or Central American River Turtle): A Working Bibliography Venetia Briggs-Gonzalez1,*, Sergio C. Gonzalez1, Dustin Smith2, Kyle Allen1, Thomas R. Rainwater3, and Frank J. Mazzotti1 Abstract - Dermatemys mawii (Central American River Turtle), locally known in Belize as the “Hicatee” and in Guatemala and Mexico as Tortuga Blanca, is a large, highly aquatic freshwater turtle that has been extirpated from much of its historical range of southern Mex- ico, northern Guatemala, and lowland Belize. Throughout its restricted range, Dermatemys has been intensely harvested for its meat and eggs and sold in local markets. -

ABSTRACTS 45Th Annual Meeting and Symposium Las Vegas, Nevada February 20–23, 2020

ABSTRACTS 45th Annual Meeting and Symposium Las Vegas, Nevada February 20–23, 2020 FORTY-FIFTH ANNUAL MEETING AND SYMPOSIUM THE DESERT TORTOISE COUNCIL LAS VEGAS, NEVADA February 19–23, 2020 ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS AND POSTERS (Abstracts arranged alphabetically by last name of first author) *Speaker, if not the first author listed Connectivity and the Framework for Recovery of the Mojave Desert Tortoise Linda J. Allison Desert Tortoise Recovery Office, US Fish and Wildlife Service, 1340 Financial Blvd. #234, Reno, Nevada 89502. Email: [email protected] The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has standards for determining whether species should have federal protection. It also has standards for describing a viable species, couched in terms of representation, redundancy, and resilience. These characteristics were used in the 1994 Recovery Plan to design and evaluate the size and location of proposed critical habitat units for the Mojave desert tortoise. Regarding long-term representation and resilience, critical habitat units were designed to sustain a population of at least 5000 adult tortoises. In situations where the critical habitat unit was smaller than the threshold of 500 sqmi or if the number of tortoises was found to be fewer than 5000, it was expected that land management would result in connectivity to larger populations outside the critical habitat unit and to other critical habitat units. At the time the original recovery plan was developed, there were no estimates of the number of tortoises in any particular critical habitat unit and little information about how tortoise populations were connected for short-term viability. In the meantime, we are able to use population estimates to evaluate connectivity management needs for critical habitat units and to describe what long- and short-term connectivity entails for tortoise populations.