The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USF Board of Trustees ( March 7, 2013)

Agenda item: (to be completed by Board staff) USF Board of Trustees ( March 7, 2013) Issue: Proposed Ph.D. in Integrative Biology ________________________________________________________________ Proposed action: New Degree Program Approval ________________________________________________________________ Background information: This application for a new Ph.D is driven by a recent reorganization of the Department of Biology. The reorganization began in 2006 and was completed in 2009. The reorganization of the Department of Biology, in part, reflected the enormity of the biological sciences, and in part, different research perspectives and directions taken by the faculty in each of the respective areas of biology. Part of the reorganization was to replace the original Ph.D. in Biology with two new doctoral degrees that better serve the needs of the State and our current graduate students by enabling greater focus of the research performed to earn the Ph.D. The well-established and highly productive faculty attracts students to the Tampa Campus from all over the United States as well as from foreign countries. The resources to support the two Ph.D. programs have already been established in the Department of Biology and are sufficient to support the two new degree programs. The reorganization created two new departments; the Department of Cell Biology, Microbiology, and Molecular Biology (CMMB) and the Department of Integrative Biology (IB). This proposal addresses the creation of a new Ph.D., in Integrative Biology offered by the Department of Integrative Biology (CIP Code 26.1399). The name of the Department, Integrative Biology, reflects the belief that the study of biological processes and systems can best be accomplished by the incorporation of numerous integrated approaches Strategic Goal(s) Item Supports: The proposed program directly supports the following: Goal 1 and Goal 2 Workgroup Review: ACE March 7, 2013 Supporting Documentation: See Complete Proposal below Prepared by: Dr. -

Body Condition Assessment – As a Welfare and Management Assessment Tool for Radiated Tortoises (Astrochelys Radiata)

Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management assessment tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Independent project • 15 hp Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SLU Department of Animal Environment and Health Programme/Education Uppsala 2020 2 Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Supervisor: Lisa Lundin, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Examiner: Maria Andersson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Credits: 15 hp Level: First cycle, G2E Course title: Independent project Course code: EX0894 Programme/education: Course coordinating dept: Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment Place of publication: Uppsala Year of publication: 2020 Cover picture: Linn Lagerström Keywords: Tortoise, turtle, radiated tortoise, Astrochelys radiata, Geochelone radiata, body condition indices, body condition score, morphometrics Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Animal Environment and Health 3 Publishing and archiving Approved students’ theses at SLU are published electronically. As a student, you have the copyright to your own work and need to approve the electronic publishing. If you check the box for YES, the full text (pdf file) and metadata will be visible and searchable online. If you check the box for NO, only the metadata and the abstract will be visiable and searchable online. Nevertheless, when the document is uploaded it will still be archived as a digital file. -

English and French Cop17 Inf

Original language: English and French CoP17 Inf. 36 (English and French only / Únicamente en inglés y francés / Seulement en anglais et français) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Johannesburg (South Africa), 24 September – 5 October 2016 JOINT STATEMENT REGARDING MADAGASCAR’S PLOUGHSHARE / ANGONOKA TORTOISE 1. This document has been submitted by the United States of America at the request of the Wildlife Conservation Society, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Turtle Survival Alliance, and The Turtle Conservancy, in relation to agenda item 73 on Tortoises and freshwater turtles (Testudines spp.)*. 2. This species is restricted to a limited range in northwestern Madagascar. It has been included in CITES Appendix I since 1975 and has been categorized as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species since 2008. There has been a significant increase in the level of illegal collection and trafficking of this species to supply the high end pet trade over the last 5 years. 3. Attached please find the joint statement regarding Madagascar’s Ploughshare/Angonoka Tortoise, which is considered directly relevant to Document CoP17 Doc. 73 on tortoises and freshwater turtles. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. -

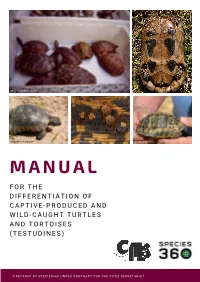

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Use of Extant Non-Indigenous Tortoises As a Restoration Tool to Replace Extinct Ecosystem Engineers

OPINION ARTICLE The Use of Extant Non-Indigenous Tortoises as a Restoration Tool to Replace Extinct Ecosystem Engineers Christine J. Griffiths,1,2,3,4 Carl G. Jones,3,5 Dennis M. Hansen,6 Manikchand Puttoo,7 Rabindra V. Tatayah,3 Christine B. Muller,¨ 2,∗ andStephenHarris1 Abstract prevent the extinction and further degradation of Round We argue that the introduction of non-native extant tor- Island’s threatened flora and fauna. In the long term, the toises as ecological replacements for extinct giant tortoises introduction of tortoises to Round Island will lead to valu- is a realistic restoration management scheme, which is able management and restoration insights for subsequent easy to implement. We discuss how the recent extinctions larger-scale mainland restoration projects. This case study of endemic giant Cylindraspis tortoises on the Mascarene further highlights the feasibility, versatility and low-risk Islands have left a legacy of ecosystem dysfunction threat- nature of using tortoises in restoration programs, with par- ening the remnants of native biota, focusing on the island ticular reference to their introduction to island ecosystems. of Mauritius because this is where most has been inferred Overall, the use of extant tortoises as replacements for about plant–tortoise interactions. There is a pressing need extinct ones is a good example of how conservation and to restore and preserve several Mauritian habitats and restoration biology concepts applied at a smaller scale can plant communities that suffer from ecosystem dysfunction. be microcosms for more grandiose schemes and addresses We discuss ongoing restoration efforts on the Mauritian more immediate conservation priorities than large-scale offshore Round Island, which provide a case study high- ecosystem rewilding projects. -

Genus Boophilus Curtice Genus Rhipicentor Nuttall & Warburton

3 CONTENTS General remarks 4 Genus Amblyomma Koch 5 Genus Anomalohimalaya Hoogstraal, Kaiser & Mitchell 46 Genus Aponomma Neumann 47 Genus Boophilus Curtice 58 Genus Hyalomma Koch. 63 Genus Margaropus Karsch 82 Genus Palpoboophilus Minning 84 Genus Rhipicentor Nuttall & Warburton 84 Genus Uroboophilus Minning. 84 References 86 SUMMARI A list of species and subspecies currently included in the tick genera Amblyomma, Aponomma, Anomalohimalaya, Boophilus, Hyalomma, Margaropus, and Rhipicentor, as well as in the unaccepted genera Palpoboophilus and Uroboophilus is given in this paper. The published synonymies and authors of each spécifie or subspecific name are also included. Remaining tick genera have been reviewed in part in a previous paper of this series, and will be finished in a future third part. Key-words: Amblyomma, Aponomma, Anomalohimalaya, Boophilus, Hyalomma, Margaropus, Rhipicentor, Uroboophilus, Palpoboophilus, species, synonymies. RESUMEN Se proporciona una lista de las especies y subespecies actualmente incluidas en los géneros Amblyomma, Aponomma, Anomalohimalaya, Boophilus, Hyalomma, Margaropus y Rhipicentor, asi como en los géneros no aceptados Palpoboophilus and Uroboophilus. Se incluyen también las sinonimias publicadas y los autores de cada nombre especifico o subespecifico. Los restantes géneros de garrapatas han sido revisados en parte en un volumen previo de esta serie, y serân terminados en una futura tercera parte. Palabras claves Amblyomma, Aponomma, Anomalohimalaya, Boophilus, Hyalomma, Margaropus, Rhipicentor, Uroboophilus, Palpoboophilus, especies, sinonimias. 4 GENERAL REMARKS Following is a list of species and subspecies of ticks d~e scribed in the genera Amblyomma, Aponomma, Anomalohimalaya, Boophilus, Hyalorma, Margaropus, and Rhipicentor, as well as in the unaccepted genera Palpoboophilus and Uroboophilus. The first volume (Estrada- Pena, 1991) included data for Haemaphysalis, Anocentor, Dermacentor, and Cosmiomma. -

Reptiles A. Cladistics 1. Many Groups of Organisms

Reptiles A. Cladistics 1. Many groups of organisms are “polyphyletic” a. This means that the group combines 2 or more lineages - example=fish 2. Cladistics follows only pure lineages going back in time - example Osteichthys B. Reptile Classifiecation - looks like a polyphyletic group 1. Dry skin - no loss of water through skin like amphibians 2. Aminotic egg - an egg that can survive on dry land - in contrast with the amphibian egg C. Mammals and Birds are derived from different lineages of reptiles (We will see below) D. Stem Reptiles 1. Different lineages based on the temporal region of their skulls - number of holes (or bars) a. These holes are necessary to accommodate large jaw muscles b. Anapsid Skull - no holes in temporal - jaws can move fast, but with little force 1. Muscles that move the jaw are small 2. There is no good paleotological evidence for the transition between amphibians and reptiles - no fossil intermediates a. Fossil amphibians have lots of dermal bones in skull b. Amphibians have no temporal openings in skull 1. (Aside) both fossil amphibians and primitive reptiles have a parietal “eye” that senses light and dark (“third” eye in middle of head) c. Reptile skull is higher than amphibian to accomodate larger jaw muscles d. Of the modern reptiles only turtles are anapsids 2. Diapsid Skull - has holes in the temporal region a. Diapsid reptiles gave rise to lizards and snakes - they have a diapsid skull 1. Also Tuatara, crocodiles, dinosaurs and pterydactyls Reptiles b. One group of diapsids also had a pre-orbital hole in the skull in front of eye - this hole is still preserved in the birds - this anatomy suggests strongly that the birds are derived from the diapsid reptiles 3. -

Aldabrachelys Arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold's Giant Tortoise

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTestudinidae of the IUCN/SSC — AldabrachelysTortoise and Freshwater arnoldi Turtle Specialist Group 028.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.028.arnoldi.v1.2009 © 2009 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 18 October 2009 Aldabrachelys arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold’s Giant Tortoise JUSTIN GERLACH 1 1133 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge CB1 7BX, United Kingdom [[email protected]] SUMMARY . – Arnold’s giant tortoise, Aldabrachelys arnoldi (= Dipsochelys arnoldi) (Family Testudinidae), from the granitic Seychelles, is a controversial species possibly distinct from the Aldabra giant tortoise, A. gigantea (= D. dussumieri of some authors). The species is a morphologi- cally distinctive morphotype, but has so far not been genetically distinguishable from the Aldabra tortoise, and is considered synonymous with that species by many researchers. Captive reared juveniles suggest that there may be a genetic basis for the morphotype and more detailed genetic work is needed to elucidate these relationships. The species is the only living saddle-backed tortoise in the Seychelles islands. It was apparently extirpated from the wild in the 1800s and believed to be extinct until recently purportedly rediscovered in captivity. The current population of this morphotype is 23 adults, including 18 captive adult males on Mahé Island, 5 adults recently in- troduced to Silhouette Island, and one free-ranging female on Cousine Island. Successful captive breeding has produced 138 juveniles to date. -

Can Unwanted Suburban Tortoises Rescue Native Hawaiian Plants?

CAN UNWANTED SUBURBAN TORTOISES RESCUE NATIVE HAWAIIAN PLANTS? by David A. Burney, James O. Juvik, Lida Pigott Burney, and Tomas Diagne 104 THE TORTOISE ・ 2012 hrough a series of coincidences, surplus pet tortoises in Hawaii may end up offering a partial solution to the seemingly insurmountable challenge posed by invasive plants in the Makauwahi Cave Reserve Ton Kaua`i. This has come about through a serendipitous intersection of events in Africa, the Mascarene Islands, North America, and Hawaii. The remote Hawaiian Islands were beyond the reach of naturally dispersing island tortoises, but the niches were apparently still there. Giant flightless ducks and geese evolved on these islands with tortoise-like beaks and other adaptations as terrestrial “meso-herbivores.” Dating of these remarkable fossil remains shows that they went extinct soon after the arrival of Polynesians at the beginning of the last millennium leaving the niches for large native herbivores entirely empty. Other native birds, including important plant pollinators, and some plant species have also suffered extinction in recent centuries. This trend accelerated after European settlement ecosystem services and a complex mix of often with the introduction of many invasive alien plants conflicting stakeholder interests clearly requires and the establishment of feral ungulate populations new paradigms and new tools. such as sheep, goats, cattle, and European swine, as Lacking any native mammalian herbivores, the well as other insidious invasives such as deer, rats, majority of the over 1,000 native Hawaiian plant mongoose, feral house cats, and even mosquitoes, species on the islands have been widely regarded which transmit avian malaria to a poorly resistant in the literature as singularly lacking in defensive native avifauna. -

Toxins-67579-Rd 1 Proofed-Supplementary

Supplementary Information Table S1. Reviewed entries of transcriptome data based on salivary and venom gland samples available for venomous arthropod species. Public database of NCBI (SRA archive, TSA archive, dbEST and GenBank) were screened for venom gland derived EST or NGS data transcripts. Operated search-terms were “salivary gland”, “venom gland”, “poison gland”, “venom”, “poison sack”. Database Study Sample Total Species name Systematic status Experiment Title Study Title Instrument Submitter source Accession Accession Size, Mb Crustacea The First Venomous Crustacean Revealed by Transcriptomics and Functional Xibalbanus (former Remipedia, 454 GS FLX SRX282054 454 Venom gland Transcriptome Speleonectes Morphology: Remipede Venom Glands Express a Unique Toxin Cocktail vReumont, NHM London SRP026153 SRR857228 639 Speleonectes ) tulumensis Speleonectidae Titanium Dominated by Enzymes and a Neurotoxin, MBE 2014, 31 (1) Hexapoda Diptera Total RNA isolated from Aedes aegypti salivary gland Normalized cDNA Instituto de Quimica - Aedes aegypti Culicidae dbEST Verjovski-Almeida,S., Eiglmeier,K., El-Dorry,H. etal, unpublished , 2005 Sanger dideoxy dbEST: 21107 Sequences library Universidade de Sao Paulo Centro de Investigacion Anopheles albimanus Culicidae dbEST Adult female Anopheles albimanus salivary gland cDNA library EST survey of the Anopheles albimanus transcriptome, 2007, unpublished Sanger dideoxy Sobre Enfermedades dbEST: 801 Sequences Infeccionsas, Mexico The salivary gland transcriptome of the neotropical malaria vector National Institute of Allergy Anopheles darlingii Culicidae dbEST Anopheles darlingi reveals accelerated evolution o genes relevant to BMC Genomics 10 (1): 57 2009 Sanger dideoxy dbEST: 2576 Sequences and Infectious Diseases hematophagyf An insight into the sialomes of Psorophora albipes, Anopheles dirus and An. Illumina HiSeq Anopheles dirus Culicidae SRX309996 Adult female Anopheles dirus salivary glands NIAID SRP026153 SRS448457 9453.44 freeborni 2000 An insight into the sialomes of Psorophora albipes, Anopheles dirus and An. -

Strategic Study of Environment Impact of the Framework Plan and Program of the Onshore Exploration and Production of Hydrocarbons

Strategic Study of Environment Impact of the Framework Plan and Program of the Onshore Exploration and Production of Hydrocarbons Non-Technical Summary Zagreb, July 2015 Consortium: Elektroprojekt d.d. STUDY IMPLEMENTERS: Alexandera von Humboldta 4, 10 000 Zagreb Ires ekologija d.o.o. za zaštitu prirode i okoliša Prilaz baruna Filipovića 21, 10 000 Zagreb STUDY LEADER: Mr.sc. Zlatko Pletikapić, BEng ASSISTANT STUDY LEADER: Mirko Mesarić, dipl. ing. biol.. COORDINATOR: Jelena Likić, prof. biol. Table of Contents 1. Description of the Framework Plan and Programme ...................................................................................... 1 2. Main objectives of the Framework Plan and Programme ............................................................................... 2 3. Overview of the previous onshore exploration and production of hydrocarbons............................................. 2 4. Technical aspects of exploration and production of hydrocarbons ................................................................. 3 5. Environmental Impact of the Framework Plan and Programme ..................................................................... 7 6. Environmental protection measures ............................................................................................................. 22 7. Environmental monitoring ............................................................................................................................. 28 8. Conclusions and recommendations ............................................................................................................. -

Farmers' Knowledge of Wild Musa in India Farmers'

FARMERS’ KNOWLEDGE OF WILD MUSA IN INDIA Uma Subbaraya National Research Centre for Banana Indian Council of Agricultural Reasearch Thiruchippally, Tamil Nadu, India Coordinated by NeBambi Lutaladio and Wilfried O. Baudoin Horticultural Crops Group Crop and Grassland Service FAO Plant Production and Protection Division FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2006 Reprint 2008 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to: Chief Publishing Management Service Information Division FAO Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to: [email protected] © FAO 2006 FARMERS’ KNOWLEDGE OF WILD MUSA IN INDIA iii CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi FOREWORD vii INTRODUCTION 1 SCOPE OF THE STUDY AND METHODS