The Use of Extant Non-Indigenous Tortoises As a Restoration Tool to Replace Extinct Ecosystem Engineers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Body Condition Assessment – As a Welfare and Management Assessment Tool for Radiated Tortoises (Astrochelys Radiata)

Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management assessment tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Independent project • 15 hp Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SLU Department of Animal Environment and Health Programme/Education Uppsala 2020 2 Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Supervisor: Lisa Lundin, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Examiner: Maria Andersson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Credits: 15 hp Level: First cycle, G2E Course title: Independent project Course code: EX0894 Programme/education: Course coordinating dept: Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment Place of publication: Uppsala Year of publication: 2020 Cover picture: Linn Lagerström Keywords: Tortoise, turtle, radiated tortoise, Astrochelys radiata, Geochelone radiata, body condition indices, body condition score, morphometrics Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Animal Environment and Health 3 Publishing and archiving Approved students’ theses at SLU are published electronically. As a student, you have the copyright to your own work and need to approve the electronic publishing. If you check the box for YES, the full text (pdf file) and metadata will be visible and searchable online. If you check the box for NO, only the metadata and the abstract will be visiable and searchable online. Nevertheless, when the document is uploaded it will still be archived as a digital file. -

KS2 Tortoise Shapes and Sizes

TORTOISE SHAPES AND SIZE... ? Not all tortoises look the same. What can you learn about a tortoise from looking at the shape of its shell? Some Galapagos tortoises have Some Galapagos tortoises have domed shells like this saddleback shells like this An adaptation is a feature an animal has which helps it survive. If an animal has a greater chance of surviving then it has a greater chance of having more babies who are also likely to have the same adaptation. In the space below, draw one of our Galapagos giant tortoises. Make notes describing the TASK 1 different adaptations of the tortoise and how those features might help the tortoise survive in the wild. Worksheet 2 KS2 1 ? Not all the Galapagos Islands have the same habitat. What can you tell about the habitat of a tortoise by looking at the shape of its shell? Some of the Galapagos Islands are Some of the Galapagos Islands are smaller and dryer, where tall cacti larger and wetter, where many plants grow. plants grow close to the ground. TASK 2 Of the two tortoise shell shapes, which is likely to be better for reaching tall cacti plants? ______________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________ Which of these island types is likely to provide enough food for tortoises to grow to large sizes? ______________________________________________________________________________________________ -

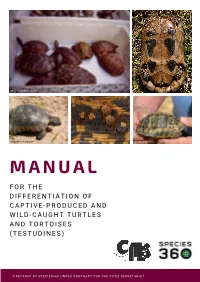

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Aldabrachelys Arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold's Giant Tortoise

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTestudinidae of the IUCN/SSC — AldabrachelysTortoise and Freshwater arnoldi Turtle Specialist Group 028.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.028.arnoldi.v1.2009 © 2009 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 18 October 2009 Aldabrachelys arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold’s Giant Tortoise JUSTIN GERLACH 1 1133 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge CB1 7BX, United Kingdom [[email protected]] SUMMARY . – Arnold’s giant tortoise, Aldabrachelys arnoldi (= Dipsochelys arnoldi) (Family Testudinidae), from the granitic Seychelles, is a controversial species possibly distinct from the Aldabra giant tortoise, A. gigantea (= D. dussumieri of some authors). The species is a morphologi- cally distinctive morphotype, but has so far not been genetically distinguishable from the Aldabra tortoise, and is considered synonymous with that species by many researchers. Captive reared juveniles suggest that there may be a genetic basis for the morphotype and more detailed genetic work is needed to elucidate these relationships. The species is the only living saddle-backed tortoise in the Seychelles islands. It was apparently extirpated from the wild in the 1800s and believed to be extinct until recently purportedly rediscovered in captivity. The current population of this morphotype is 23 adults, including 18 captive adult males on Mahé Island, 5 adults recently in- troduced to Silhouette Island, and one free-ranging female on Cousine Island. Successful captive breeding has produced 138 juveniles to date. -

Origins of Endemic Island Tortoises in the Western Indian Ocean: a Critique of the Human-Translocation Hypothesis

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 Origins of endemic island tortoises in the western Indian Ocean: a critique of the human-translocation hypothesis Hansen, Dennis M ; Austin, Jeremy J ; Baxter, Rich H ; de Boer, Erik J ; Falcón, Wilfredo ; Norder, Sietze J ; Rijsdijk, Kenneth F ; Thébaud, Christophe ; Bunbury, Nancy J ; Warren, Ben H Abstract: How do organisms arrive on isolated islands, and how do insular evolutionary radiations arise? In a recent paper, Wilmé et al. (2016a) argue that early Austronesians that colonized Madagascar from Southeast Asia translocated giant tortoises to islands in the western Indian Ocean. In the Mascarene Islands, moreover, the human-translocated tortoises then evolved and radiated in an endemic genus (Cylindraspis). Their proposal ignores the broad, established understanding of the processes leading to the formation of native island biotas, including endemic radiations. We find Wilmé et al.’s suggestion poorly conceived, using a flawed methodology and missing two critical pieces of information: the timing and the specifics of proposed translocations. In response, we here summarize the arguments thatcould be used to defend the natural origin not only of Indian Ocean giant tortoises but also of scores of insular endemic radiations world-wide. Reinforcing a generalist’s objection, the phylogenetic and ecological data on giant tortoises, and current knowledge of environmental and palaeogeographical history of the Indian Ocean, make Wilmé et al.’s argument even more unlikely. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12893 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-131419 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Hansen, Dennis M; Austin, Jeremy J; Baxter, Rich H; de Boer, Erik J; Falcón, Wilfredo; Norder, Sietze J; Rijsdijk, Kenneth F; Thébaud, Christophe; Bunbury, Nancy J; Warren, Ben H (2017). -

The Relationships Between Length and Weight of the Aldabra Giant Tortoise, Dipsochelys Dussumieri, in Mauritius

The relationships between length and weight of the Aldabra giant tortoise, Dipsochelys dussumieri, in Mauritius L. Aworer & R. Ramchurn* *Faculty of Agriculture, University of Mauritius, Réduit, MAURITIUS [[email protected] / [email protected]] Abstract: In the Republic of Mauritius Aldabra giant tortoises, Dipsochelys dussumieri (also known as Geo- chelone gigantea), are kept in captivity mainly in private parks, public gardens, a few sugar estates and by some people as pets . The study was carried out in two private parks: Casela and La Vanille and two public gardens, SSR Botanical Garden at Pamplemousses and Balfour Garden. The private parks were better managed and maintained by virtue of their commercial purpose. Improvements were needed for Balfour Garden. Regressions were established between straight, curved carapace lengths and weight of juveniles, adults, both males and females. Regressions for adult males and females were compared using two different methods (straight and curved carapace lengths). A strong positive relationship was observed between the weight and straight carapace length of juveniles (R2=0.96) and adult males (R2=0.88), whereas, for adult females there was a weaker relationship (R2=0.69). The same coefficient of regression was observed when the curved carapace length was regressed with weights for juveniles. A strong positive relationship was observed between weight and curved carapace length of adult males (R2=0.94), and for adult females there was a positive relationship (R2=0.74). From the work carried out, it had been found that both methods could be used to estimate weights of the tortoises using their respective equations. The equation for straight carapace length was Log Y = 2.47Log X + 0.2 (Y = weight in grammes; X = length in cm). -

RADIATED TORTOISE Testudines Family: Testudinidae Genus: Astrochelys Species: Radiata

RADIATED TORTOISE Testudines Family: Testudinidae Genus: Astrochelys Species: radiata Range: Southern Madagascar Habitat: dry regions of brush, thorn forests, and woodlands Niche: Terrestrial, diurnal, herbivorous Wild diet: grasses, fruit and succulent plants Zoo diet: Life Span: (Wild) 40 – 50 years (Captivity) up to 100 years Sexual dimorphism: Male has longer tail and more protruding scutes, the notch in the plastron beneath the tail is more noticeable. Location in SF Zoo: Children’s Zoo, Koret Animal Resource Center APPEARANCE & PHYSICAL ADAPTATIONS: The radiated tortoise has a high-domed carapace with yellow lines running down from the center of the dark plate of the shell. This pattern appears to radiate from the shell, hence the name, radiated tortoise. The radiating lines extend down the scutes, the shell’s plates. Its legs and feet are yellow as is its head, except for a black patch on top. This Weight: 35 lbs tortoise has a blunt head, and elephantine feet. Juveniles are black and off- white when they hatch, but quickly develop the adult's striking coloration. Length: 16 in Their strong legs and round, stumpy feet made for walking on land. Their front limbs are flattened with well-developed muscle and sharp claw-like scales adapted for burrowing. The shell is supplied with blood vessels and nerves so like other tortoises it can feel when being touched. STATUS & CONSERVATION The radiated tortoise is listed in Appendix I of CITES. These tortoises are critically endangered due to loss of habitat, being poached for food, and being over exploited in the pet trade. Some Chinese will pay the equivalent of $50 for a radiated tortoise to eat (they are also believed to have aphrodisiac properties). -

Human Translocation As an Alternative Hypothesis to Explain the Presence of Giant Tortoises on Remote Islands in the Southwestern Indian Ocean

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298072054 Human translocation as an alternative hypothesis to explain the presence of giant tortoises on remote islands in the Southwestern Indian Ocean ARTICLE in JOURNAL OF BIOGEOGRAPHY · MARCH 2016 Impact Factor: 4.59 · DOI: 10.1111/jbi.12751 READS 63 3 AUTHORS: Lucienne Wilmé Patrick Waeber Missouri Botanical Garden ETH Zurich 50 PUBLICATIONS 599 CITATIONS 37 PUBLICATIONS 113 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Jörg U. Ganzhorn University of Hamburg 208 PUBLICATIONS 5,425 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: Lucienne Wilmé letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 18 March 2016 Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2016) PERSPECTIVE Human translocation as an alternative hypothesis to explain the presence of giant tortoises on remote islands in the south-western Indian Ocean Lucienne Wilme1,2,*, Patrick O. Waeber3 and Joerg U. Ganzhorn4 1School of Agronomy, Water and Forest ABSTRACT Department, University of Antananarivo, Giant tortoises are known from several remote islands in the Indian Ocean Madagascar, 2Missouri Botanical Garden, (IO). Our present understanding of ocean circulation patterns, the age of the Madagascar Research & Conservation Program, Madagascar, 3Forest Management islands, and the life history traits of giant tortoises makes it difficult to com- and Development, Department of prehend how these animals arrived -

ECUADOR – Galapagos Giant Tortoises Stolen From

CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA NOTIFICATION TO THE PARTIES No. 2018/076 Geneva, 30 October 2018 CONCERNING: ECUADOR Galapagos giant tortoises stolen from breeding center 1. This Notification is being published at the request of Ecuador. 2. The CITES Management Authority of Ecuador informed the Secretariat that on 27 September 2018, the Galapagos National Park Directorate filed a criminal complaint in Ecuador following the theft of 123 live Galapagos giant tortoises (Chelonoidis niger) from the Galapagos National Park breeding center on Isabela Island. 3. The Galapagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis niger1) is included in CITES Appendix I. 4. The stolen tortoises range from one to six years in age. One-year-old Galapagos giant tortoises may be around six centimetres in carapace length and weigh an estimated 200 grams. A six-year-old Galapagos giant tortoise could range from 12 to 30 centimetres in carapace length, and weigh around two kilograms. 5. The likely market for the stolen specimens is outside of Ecuador, and the CITES Management Authority of Ecuador therefore requests that the present Notification be distributed as widely as possible among police, customs and wildlife enforcement authorities. 6. Parties are requested to inform the CITES Management Authority of Ecuador should any permits or certificates regarding trade in these specimens be received. The Management Authority of Ecuador also requests that CITES Management Authorities do not approve any export, import or re-export permit applications related to this species before consulting with the CITES Management Authority of Ecuador. 7. Parties that seize illegally traded specimens of Chelonoidis niger are also requested to communicate information about these seizures to the Management Authority of Ecuador. -

Seychelles Giant Tortoise

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTestudinidae of the IUCN/SSC — Aldabrachelys Tortoise and Freshwater hololissa Turtle Specialist Group 061.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.061.hololissa.v1.2011 © 2011 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 31 December 2011 Aldabrachelys hololissa (Günther 1877) – Seychelles Giant Tortoise JUSTIN GERLACH 1 1133 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge, CB1 7BX United Kingdom [[email protected]] SUMMARY . – The Seychelles Giant Tortoise, Aldabrachelys hololissa (= Dipsochelys hololissa) (Family Testudinidae) is a controversial species possibly distinct from the Aldabra giant tor- toise, A. gigantea (= D. dussumieri of some authors). The species is a morphologically distinctive morphotype, but has so far not been genetically distinguishable from the Aldabra tortoise, and is considered by many researchers to be either synonymous with or only subspecifically distinct from that taxon. It is a domed grazing species, differing from the Aldabra tortoise in its broader shape and reduced ossification of the skeleton; it differs also from the other controversial giant tortoise in the Seychelles, the saddle-backed morphotype A. arnoldi. Aldabrachelys hololissa was apparently extirpated from the wild in the 1800s and is now known only from 37 adults, including 28 captive, 1 free-ranging on Cerf Island, and 8 on Cousine Island, 6 of which were released in 2011 along with 40 captive bred juveniles. Captive reared juveniles show that there is a presumed genetic basis to the morphotype and further genetic work is needed to elucidate this. -

Giant Tortoises with Pinta Island Ancestry Identified In

Biological Conservation 157 (2013) 225–228 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Short communication The genetic legacy of Lonesome George survives: Giant tortoises with Pinta Island ancestry identified in Galápagos a, a a,b c d Danielle L. Edwards ⇑, Edgar Benavides , Ryan C. Garrick , James P. Gibbs , Michael A. Russello , Kirstin B. Dion a, Chaz Hyseni a, Joseph P. Flanagan e, Washington Tapia f, Adalgisa Caccone a a Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA b Department of Biology, University of Mississippi, MS 38677, USA c College of Environmental Science and Forestry, State University of New York, Syracuse, NY 13210, USA d Department of Biology, University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus, Kelowna, BC, Canada V1V 1V7 e Houston Zoo, Houston, TX 77030, USA f Galápagos National Park Service, Puerto Ayora, Galápagos, Ecuador article info abstract Article history: The death of Lonesome George, the last known purebred individual of Chelonoidis abingdoni native to Received 22 August 2012 Pinta Island, marked the extinction of one of 10 surviving giant tortoise species from the Galápagos Archi- Received in revised form 9 October 2012 pelago. Using a DNA reference dataset including historical C. abingdoni and >1600 living Volcano Wolf Accepted 14 October 2012 tortoise samples, a site on Isabela Island known to harbor hybrid tortoises, we discovered 17 individuals with ancestry in C. abingdoni. These animals belong to various hybrid categories, including possible first generation hybrids, and represent multiple, unrelated individuals. Their ages and relative abundance sug- Keywords: gest that additional hybrids and conceivably purebred C.