Movement, Home Range and Habitat Use in Leopard Tortoises (Stigmochelys Pardalis) on Commercial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Body Condition Assessment – As a Welfare and Management Assessment Tool for Radiated Tortoises (Astrochelys Radiata)

Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management assessment tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Independent project • 15 hp Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SLU Department of Animal Environment and Health Programme/Education Uppsala 2020 2 Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Supervisor: Lisa Lundin, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Examiner: Maria Andersson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Credits: 15 hp Level: First cycle, G2E Course title: Independent project Course code: EX0894 Programme/education: Course coordinating dept: Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment Place of publication: Uppsala Year of publication: 2020 Cover picture: Linn Lagerström Keywords: Tortoise, turtle, radiated tortoise, Astrochelys radiata, Geochelone radiata, body condition indices, body condition score, morphometrics Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Animal Environment and Health 3 Publishing and archiving Approved students’ theses at SLU are published electronically. As a student, you have the copyright to your own work and need to approve the electronic publishing. If you check the box for YES, the full text (pdf file) and metadata will be visible and searchable online. If you check the box for NO, only the metadata and the abstract will be visiable and searchable online. Nevertheless, when the document is uploaded it will still be archived as a digital file. -

Chelonian Perivitelline Membrane-Bound Sperm Detection: a New Breeding Management Tool

Zoo Biology 35: 95–103 (2016) RESEARCH ARTICLE Chelonian Perivitelline Membrane-Bound Sperm Detection: A New Breeding Management Tool Kaitlin Croyle,1,2 Paul Gibbons,3 Christine Light,3 Eric Goode,3 Barbara Durrant,1 and Thomas Jensen1* 1San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, Escondido, California 2Department of Biological Sciences, California State University San Marcos, San Marcos, California 3Turtle Conservancy, New York, New York Perivitelline membrane (PVM)-bound sperm detection has recently been incorporated into avian breeding programs to assess egg fertility, confirm successful copulation, and to evaluate male reproductive status and pair compatibility. Due to the similarities between avian and chelonian egg structure and development, and because fertility determination in chelonian eggs lacking embryonic growth is equally challenging, PVM-bound sperm detection may also be a promising tool for the reproductive management of turtles and tortoises. This study is the first to successfully demonstrate the use of PVM-bound sperm detection in chelonian eggs. Recovered membranes were stained with Hoechst 33342 and examined for sperm presence using fluorescence microscopy. Sperm were positively identified for up to 206 days post-oviposition, following storage, diapause, and/or incubation, in 52 opportunistically collected eggs representing 12 species. However, advanced microbial infection frequently hindered the ability to detect membrane-bound sperm. Fertile Centrochelys sulcata, Manouria emys,andStigmochelys pardalis eggs were used to evaluate the impact of incubation and storage on the ability to detect sperm. Storage at À20°C or in formalin were found to be the best methods for egg preservation prior to sperm detection. Additionally, sperm-derived mtDNA was isolated and PCR amplified from Astrochelys radiata, C. -

English and French Cop17 Inf

Original language: English and French CoP17 Inf. 36 (English and French only / Únicamente en inglés y francés / Seulement en anglais et français) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Johannesburg (South Africa), 24 September – 5 October 2016 JOINT STATEMENT REGARDING MADAGASCAR’S PLOUGHSHARE / ANGONOKA TORTOISE 1. This document has been submitted by the United States of America at the request of the Wildlife Conservation Society, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Turtle Survival Alliance, and The Turtle Conservancy, in relation to agenda item 73 on Tortoises and freshwater turtles (Testudines spp.)*. 2. This species is restricted to a limited range in northwestern Madagascar. It has been included in CITES Appendix I since 1975 and has been categorized as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species since 2008. There has been a significant increase in the level of illegal collection and trafficking of this species to supply the high end pet trade over the last 5 years. 3. Attached please find the joint statement regarding Madagascar’s Ploughshare/Angonoka Tortoise, which is considered directly relevant to Document CoP17 Doc. 73 on tortoises and freshwater turtles. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. -

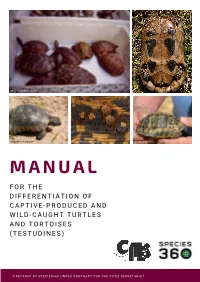

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Turtles #1 Among All Species in Race to Extinction

Turtles #1 among all Species in Race to Extinction Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation and Colleagues Ramp Up Awareness Efforts After Top 25+ Turtles in Trouble Report Published Washington, DC (February 24, 2011)―Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation (PARC), an Top 25 Most Endangered Tortoises and inclusive partnership dedicated to the conservation of Freshwater Turtles at Extremely High Risk the herpetofauna--reptiles and amphibians--and their of Extinction habitats, is calling for more education about turtle Arranged in general and approximate conservation after the Turtle Conservation Coalition descending order of extinction risk announced this week their Top 25+ Turtles in Trouble 1. Pinta/Abingdon Island Giant Tortoise report. PARC initiated a year-long awareness 2. Red River/Yangtze Giant Softshell Turtle campaign to drive attention to the plight of turtles, now the fastest disappearing species group on the planet. 3. Yunnan Box Turtle 4. Northern River Terrapin 5. Burmese Roofed Turtle Trouble for Turtles 6. Zhou’s Box Turtle The Turtle Conservation Coalition has highlighted the 7. McCord’s Box Turtle Top 25 most endangered turtle and tortoise species 8. Yellow-headed Box Turtle every four years since 2003. This year the list included 9. Chinese Three-striped Box Turtle/Golden more species than previous years, expanding the list Coin Turtle from a Top 25 to Top 25+. According to the report, 10. Ploughshare Tortoise/Angonoka between 48 and 54% of all turtles and tortoises are 11. Burmese Star Tortoise considered threatened, an estimate confirmed by the 12. Roti Island/Timor Snake-necked Turtle Red List of the International Union for the 13. -

Aldabrachelys Arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold's Giant Tortoise

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTestudinidae of the IUCN/SSC — AldabrachelysTortoise and Freshwater arnoldi Turtle Specialist Group 028.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.028.arnoldi.v1.2009 © 2009 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 18 October 2009 Aldabrachelys arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold’s Giant Tortoise JUSTIN GERLACH 1 1133 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge CB1 7BX, United Kingdom [[email protected]] SUMMARY . – Arnold’s giant tortoise, Aldabrachelys arnoldi (= Dipsochelys arnoldi) (Family Testudinidae), from the granitic Seychelles, is a controversial species possibly distinct from the Aldabra giant tortoise, A. gigantea (= D. dussumieri of some authors). The species is a morphologi- cally distinctive morphotype, but has so far not been genetically distinguishable from the Aldabra tortoise, and is considered synonymous with that species by many researchers. Captive reared juveniles suggest that there may be a genetic basis for the morphotype and more detailed genetic work is needed to elucidate these relationships. The species is the only living saddle-backed tortoise in the Seychelles islands. It was apparently extirpated from the wild in the 1800s and believed to be extinct until recently purportedly rediscovered in captivity. The current population of this morphotype is 23 adults, including 18 captive adult males on Mahé Island, 5 adults recently in- troduced to Silhouette Island, and one free-ranging female on Cousine Island. Successful captive breeding has produced 138 juveniles to date. -

Can Unwanted Suburban Tortoises Rescue Native Hawaiian Plants?

CAN UNWANTED SUBURBAN TORTOISES RESCUE NATIVE HAWAIIAN PLANTS? by David A. Burney, James O. Juvik, Lida Pigott Burney, and Tomas Diagne 104 THE TORTOISE ・ 2012 hrough a series of coincidences, surplus pet tortoises in Hawaii may end up offering a partial solution to the seemingly insurmountable challenge posed by invasive plants in the Makauwahi Cave Reserve Ton Kaua`i. This has come about through a serendipitous intersection of events in Africa, the Mascarene Islands, North America, and Hawaii. The remote Hawaiian Islands were beyond the reach of naturally dispersing island tortoises, but the niches were apparently still there. Giant flightless ducks and geese evolved on these islands with tortoise-like beaks and other adaptations as terrestrial “meso-herbivores.” Dating of these remarkable fossil remains shows that they went extinct soon after the arrival of Polynesians at the beginning of the last millennium leaving the niches for large native herbivores entirely empty. Other native birds, including important plant pollinators, and some plant species have also suffered extinction in recent centuries. This trend accelerated after European settlement ecosystem services and a complex mix of often with the introduction of many invasive alien plants conflicting stakeholder interests clearly requires and the establishment of feral ungulate populations new paradigms and new tools. such as sheep, goats, cattle, and European swine, as Lacking any native mammalian herbivores, the well as other insidious invasives such as deer, rats, majority of the over 1,000 native Hawaiian plant mongoose, feral house cats, and even mosquitoes, species on the islands have been widely regarded which transmit avian malaria to a poorly resistant in the literature as singularly lacking in defensive native avifauna. -

Origins of Endemic Island Tortoises in the Western Indian Ocean: a Critique of the Human-Translocation Hypothesis

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 Origins of endemic island tortoises in the western Indian Ocean: a critique of the human-translocation hypothesis Hansen, Dennis M ; Austin, Jeremy J ; Baxter, Rich H ; de Boer, Erik J ; Falcón, Wilfredo ; Norder, Sietze J ; Rijsdijk, Kenneth F ; Thébaud, Christophe ; Bunbury, Nancy J ; Warren, Ben H Abstract: How do organisms arrive on isolated islands, and how do insular evolutionary radiations arise? In a recent paper, Wilmé et al. (2016a) argue that early Austronesians that colonized Madagascar from Southeast Asia translocated giant tortoises to islands in the western Indian Ocean. In the Mascarene Islands, moreover, the human-translocated tortoises then evolved and radiated in an endemic genus (Cylindraspis). Their proposal ignores the broad, established understanding of the processes leading to the formation of native island biotas, including endemic radiations. We find Wilmé et al.’s suggestion poorly conceived, using a flawed methodology and missing two critical pieces of information: the timing and the specifics of proposed translocations. In response, we here summarize the arguments thatcould be used to defend the natural origin not only of Indian Ocean giant tortoises but also of scores of insular endemic radiations world-wide. Reinforcing a generalist’s objection, the phylogenetic and ecological data on giant tortoises, and current knowledge of environmental and palaeogeographical history of the Indian Ocean, make Wilmé et al.’s argument even more unlikely. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12893 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-131419 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Hansen, Dennis M; Austin, Jeremy J; Baxter, Rich H; de Boer, Erik J; Falcón, Wilfredo; Norder, Sietze J; Rijsdijk, Kenneth F; Thébaud, Christophe; Bunbury, Nancy J; Warren, Ben H (2017). -

(Geochelone Pardalis) on Farmland in the Nama-Karoo

THE STATUS AND ECOLOGY OF THE LEOPARD TORTOISE (GEOCHELONE PARDALIS) ON FARMLAND IN THE NAMA-KAROO MEGAN KAY McMASTER Submitted in fulfilment ofthe academic requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE School ofBotany and Zoology University ofNatal Pieterrnaritzburg March 2001 Preface The experimental work described in this dissertation was carried out in the School of Botany and Zoology, University ofNatal, Pietermaritzburg, from November 1997 to March 2001, under the supervision ofDr. Colleen T. Downs. This study is the original work ofthe author and has not been submitted in any form for any diploma or degree to another university. Where use has been made ofthe work of others, it is duly acknowledged in the text. Each chapter is written in the format ofthe journal it has been submitted to. ..fj~K'. Megan Kay McMaster Pietermaritzburg March 2001 11 This thesis is dedicated to myfather, the late Eric Ralph McMaster, for his constant encouragement and beliefin me, and to my brother, the late Gregory CIifton McMaster,for always making me smile. III Abstract The Family Testudinidae (Suborder Cryptodira) is represented by 40 species worldwide and reaches its greatest diversity in southern Africa, where 14 species occur (33%), ten of which are endemic to the subcontinent. Despite the strong representation ofterrestrial tortoise species in southern Africa, and the importance ofthe Karoo as a centre of endemism ofthese tortoise species, there is a paucity ofecological information for most tortoise species in South Africa. With chelonians being protected in < 15% ofall southern African reserves it is necessary to find out more about the ecological requirements, status, population dynamics and threats faced by South African tortoise species to enable the formulation ofeffective conservation measures. -

Leopard Tortoise Stigmochelys Pardalis

Leopard Tortoise Stigmochelys pardalis Class: Sauropsida Order: Chelonia Family: Testudinidae Characteristics: The leopard tortoise is the fourth largest tortoise species in the world. They get their name from their color pattern on the elevated carapace, or shell. The rings of yellow, tan, and brown resemble leopard spots. These tortoises can reach up to two feet in length and weigh up to 80 pounds (National Zoo). Tortoises lack ears, but can sense vibrations from the surrounding environment. They also lack teeth, but have a sharp beak for tearing into foods. These tortoises are well adapted to hot, arid areas (Maryland Zoo). Range & Habitat: Leopard tortoises are found in Behavior: sub-Saharan Africa, from Sudan Leopard tortoises are considered crepuscular. They try to seek shade and south to the Cape Province of avoid activity during the hottest parts of the day in the savannah sun. They South Africa. They are often found spend most of their time grazing on grasses (Maryland Zoo). If threatened, in savannah grasslands (Reptile a leopard tortoise has been known to poop on its predator. Males compete Database). for females during mating season by pushing each other until one is flipped upside down (National Zoo). Reproduction: Females will dig a nest about one foot deep and will lay up to 30 eggs in the nest. The eggs will hatch about 18 months after they are laid. Neither the male nor female are involved in parenting the offspring. Diet: Wild: grasses and succulents (prickly pear cactus) Zoo: mixed greens, sweet potato, apple, carrot, tomato, oranges, clovite, Lifespan: over 100 years in hay, tortoise pellet. -

Leopard Tortoise Care

RVC Exotics Service Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street London NW1 0TU T: 0207 554 3528 F: 0207 388 8124 www.rvc.ac.uk/BSAH LEOPARD TORTOISE CARE Leopard tortoises are large tortoises, originating from the grasslands of sub-Saharan Africa. It is essential not to underestimate the space and resources needed to look after these tortoises which will grow very large. It is important to note that these tortoises do not hibernate. HOUSING • Tortoises make poor vivarium subjects. Ideally a floor pen or tortoise table should be created. This needs to have solid sides (1 foot high) for most tortoises. Many are made out of wood or plastic. As large an area as possible should be provided, but as the size increases extra basking sites will need to be provided. For a small juvenile at least 90 cm (3 feet) long x 30 cm (1 foot) wide is recommended. This is required to enable a thermal gradient to be created along the length of the tank (hot to cold). • Hides are required to provide some security. Artificial plants, cardboard boxes, plant pots, logs or commercially available hides can be used. They should be placed both at the warm and cooler ends of the tank. • Substrates suitable for housing tortoises include newspaper, Astroturf, and some of the commercially available substrates. Natural substrate such as soil may also be used to allow for digging. It is important that the substrates either cannot be eaten, or if they are, do not cause blockages as this can prove fatal. Wood chip based substrates should never be used for this reason.