Characterization of Texas Tortoise (Gopherus Berlandieri)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texas Tortoise

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE TEXAS TORTOISE, CONTACT: ∙ TPWD: 800-792-1112 OF THE FOUR SPECIES OF TORTOISES FOUND http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/ IN NORTH AMERICA, THE TEXAS TORTOISE TEXAS ∙ Gulf Coast Turtle and Tortoise Society: IS THE ONLY ONE FOUND IN TEXAS. 866-994-2887 http://www.gctts.org/ THE TEXAS TORTOISE CAN BE FOUND IF YOU FIND A TEXAS TORTOISE THROUGHOUT SOUTHERN TEXAS AS WELL AS (OUT OF HABITAT), CONTACT: TORTOISE ∙ TPWD Law Enforcement TORTOISE NORTHEASTERN MEXICO. ∙ Permitted rehabbers in your area http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/huntwild/wild/rehab/ GOPHERUS BERLANDIERI UNFORTUNATELY EVERYTHING THERE ARE MANY THREATS YOU NEED TO KNOW TO THE SURVIVAL OF THE ABOUT THE STATE’S ONLY TEXAS TORTOISE: NATIVE TORTOISE HABITAT LOSS | ILLEGAL COLLECTION & THE THREATS IT FACES ROADSIDE MORTALITIES | PREDATION EXOTIC PATHOGENS TexasTortoise_brochure_V3.indd 1 3/28/12 12:12 PM COUNTIES WHERE THE TEXAS TORTOISE IS LISTED THE TEXAS TORTOISE (Gopherus berlandieri) is the smallest of the North American tortoises, reaching a shell length of about TEXAS TORTOISE AS A THREATENED SPECIES 8½ inches (22cm). The Texas tortoise can be distinguished CAN BE FOUND IN THE STATE OF TEXAS AND THEREFORE from other turtles found in Texas by its cylindrical and IS PROTECTED BY STATE LAW. columnar hind legs and by the yellow-orange scutes (plates) on its carapace (upper shell). IT IS ILLEGAL TO COLLECT, POSSESS, OR HARM A TEXAS TORTOISE. PENALTIES CAN INCLUDE PAYING A FINE OF Aransas, Atascosa, Bee, Bexar, Brewster, $273.50 PER TORTOISE. Brooks, Calhoun, Cameron, De Witt, Dimmit, Duval, Edwards, Frio, Goliad, Gonzales, Guadalupe, Hidalgo, Jackson, Jim Hogg, Jim Wells, Karnes, Kenedy, Kinney, Kleberg, La Salle, Lavaca, Live Oak, Matagorda, Maverick, McMullen, Medina, Nueces, WHAT SHOULD YOU Refugio, San Patricio, Starr, Sutton, Terrell, Uvalde, Val Verde, Victoria, Webb, Willacy, DO IF YOU FIND A Wilson, Zapata, Zavala TEXAS TORTOISE? THE TEXAS TORTOISE IS THE SMALLEST IN THE WILD AN INDIVIDUAL TEXAS TORTOISE LEAVE IT ALONE. -

Egyptian Tortoise (Testudo Kleinmanni)

EAZA Reptile Taxon Advisory Group Best Practice Guidelines for the Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) First edition, May 2019 Editors: Mark de Boer, Lotte Jansen & Job Stumpel EAZA Reptile TAG chair: Ivan Rehak, Prague Zoo. EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (May 2019) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA Reptile TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. EAZA Preamble Right from the very beginning it has been the concern of EAZA and the EEPs to encourage and promote the highest possible standards for husbandry of zoo and aquarium animals. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

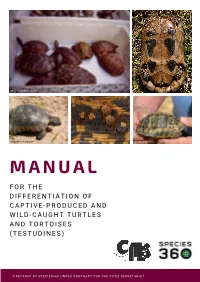

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Nest Guarding in the Gopher Tortoise (Gopherus Polyphemus)

148 CHELONIAN CONSERVATION AND BIOLOGY, Volume 11, Number 1 – 2012 Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 2012, 11(1): 148–151 g 2012 Chelonian Research Foundation Nest Guarding in the Gopher Tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) 1 1 ANDREW M. GROSSE ,KURT A. BUHLMANN , 1 1 BESS B. HARRIS ,BRETT A. DEGREGORIO , 2 1 BRETT M. MOULE ,ROBERT V. H ORAN III , AND 1 TRACEY D. TUBERVILLE 1Savannah River Ecology Lab, University of Georgia, Aiken, South Carolina 29802 USA [[email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]]; 2South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Columbia, South Carolina 29201 USA [[email protected]] ABSTRACT. – Nest guarding is rarely observed among reptiles. Specifically, turtles and tortoises are generally perceived as providing no nest protection once the eggs are laid. Here, we describe observations of nest guarding by female gopher tortoises (Gopherus poly- phemus). Nest guarding among reptiles is considered uncom- mon (Reynolds et al. 2002). Although many crocodilians are known to protect their nests and offspring from potential predators, turtles and tortoises are generally NOTES AND FIELD REPORTS 149 perceived as providing no parental care once the egg around the southeastern United States, have been laying process is complete. However, some tortoise translocated and penned in 1-ha enclosures for at least species have been observed defending their nests from one year to increase site fidelity by limiting dispersal after potential predators, namely the desert tortoise (Gopherus pen removal (Tuberville et al. 2005). One such pen was agassizii; Vaughan and Humphrey 1984) and Asian removed in July 2009, and all tortoises (n 5 14) were brown tortoise (Manouria emys; McKeown 1990; Eggen- equipped with Holohil (Ontario, Canada) AI-2F transmit- schwiler 2003; Bonin et al. -

Genetic Origins and Population Status of Desert Tortoises in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California: Initial Steps Towards Population Monitoring

G ENETIC ORIGINS AND POPULATION STATUS OF DESERT TORTOISES IN A NZA-BORREGO DESERT STATE PARK, CALIFORNIA: INITIAL STEPS TOWARDS POPULATION MONITORING Jeffrey A. Manning, Ph.D. Environmental Scientist California Department of Parks and Recreation Colorado Desert District 200 Palm Canyon Drive Borrego Springs, California 92004 November 2018 Manning, J.A. 2018. Genetic origins and population status of desert tortoises in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California: initial steps towards population monitoring. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Colorado Desert District, Borrego Springs, California. 89 pages. i Genetic Origins and Population Status of Desert Tortoises in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California: Initial Steps Towards Population Monitoring Final Report Jeffrey A. Manning, Ph.D., Author / Principle Investigator California Department of Parks and Recreation Colorado Desert District 200 Palm Canyon Drive Borrego Springs, California 92004 November 2018 Manning, J.A. 201 8. Genetic origins and population status of desert tortoises in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California: initial steps towards population monitoring. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Colorado Desert District, Borrego Springs, California. 89 pages. i FOREWORD The Desert tortoise (Gopherus sp.) was formally reported to science in 1861, and became the official California state reptile in 1972. Recent studies reveal three species, the Mojave desert tortoise (G. agassizii), Sonoran Desert tortoise (G. morafkai), and Sinaloan desert tortoise (G. evgoodei) (Murphy et al. 2011, Edwards et al. 2016; Figure 1). Range-wide declines in the Mojave desert tortoise population led California to prohibit the collection of this species in 1961. Despite this, it was emergency listed as federally endangered and state listed as threatened in 1989, and subsequently listed as federally threatened in 1990 (Federal Register 55, No 63, 50 CFR Part 17). -

Setting the Stage for Understanding Globalization of the Asian Turtle Trade

Setting the Stage for Understanding Globalization of the Asian Turtle Trade: Global, Asian, and American Turtle Diversity, Richness, Endemism, and IUCN Red List Threat Levels Anders G.J. Rhodin and Peter Paul van Dijk IUCN Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, Chelonian Research Foundation, Conservation International Thursday, January 20, 2011 New Species Described 2010 Photo C. Hagen Graptemys pearlensis - Pearl River Map Turtle Louisiana and Mississippi, USA Red List: Not Evaluated [Endangered] Thursday, January 20, 2011 IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group Founded 1980 www.iucn-tftsg.org Thursday, January 20, 2011 International Union for the Conservation of Nature / Species Survival Commission www.iucn.org Thursday, January 20, 2011 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora www.cites.org Thursday, January 20, 2011 Chelonian Conservation and Biology Thomson Reuters’ ISI Journal Citation Impact Factor currently ranks CCB among the top 100 zoology journals worldwide www.chelonianjournals.org Thursday, January 20, 2011 Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises www.iucn-tftsg.org/cbftt Thursday, January 20, 2011 IUCN Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group Members: Work or Focus - 2010 274 Members - 107 Countries Thursday, January 20, 2011 Species, Additional Subspecies, and Total Taxa of Turtles and Tortoises 500 Species Add. Subspecies 375 Total Taxa 250 125 0 1758176617831789179218011812183518441856187318891909193419551961196719771979198619891992199420062007200820092010 Currently Recognized: 334 species, 127 add. subspecies, 461 total taxa Thursday, January 20, 2011 Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Species Richness Buhlmann, Akre, Iverson, Karapatakis, Mittermeier, Georges, Rhodin, van Dijk, and Gibbons. 2009. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 8:116–149. Thursday, January 20, 2011 Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Species Richness – Global Rankings 1. -

Texas Tortoise – Gopherus Berlandieri (Agassiz 1857*) - Darrell Senneke and Chris Tabaka DVM Copyright © 2003 World Chelonian Trust

Texas tortoise – Gopherus berlandieri (Agassiz 1857*) - Darrell Senneke and Chris Tabaka DVM Copyright © 2003 World Chelonian Trust. All rights reserved * ORIGINAL NAME: Xerobates berlandieri, also known as Tortuga de Tamaulipas and Berlandier’s Tortoise. Mr. Berlandier was a zealous French naturalist, to whom we are indebted for much of what we know of the natural history of northern Mexico. This care sheet is intended only to cover the general care of this species. Further research to best develop a maintenance plan for whichever species/subspecies you are caring for is essential. For many of the older keepers in the United States this was the very first tortoise that they owned. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, they could be found in many of the “five and dimes” of the day such as SS Kresge (now Kmart) and FW Woolworths (now Footlocker) for as little as five dollars apiece. With the knowledge of how to provide for tortoises in those days being virtually non- existent, sadly nearly all of these “first” tortoises died, much like the stores that sold them. The Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlandieri) is found from South-Central Texas in the United States southward into the Mexican States of Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, and Tamaulipas. It is the smallest of the Gopherus species growing to only about 8.5 inches (22 cm) SCL. The species is listed internationally as a CITES II species and is federally listed in the United States under the Endangered Species Act. Because of this protected status, it is illegal to collect a Texas tortoise from the wild in the United States. -

Sustainable Trade in Turtles and Tortoises

Action Plan for North America Sustainable Trade in Turtles and Tortoises Commission for Environmental Cooperation Please cite as: CEC. 2017. Sustainable Trade in Turtles and Tortoises: Action Plan for North America. Montreal, Canada: Commission for Environmental Cooperation. 60 pp. This report was prepared by Peter Paul van Dijk and Ernest W.T. Cooper, of E. Cooper Environmental Consulting, for the Secretariat of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC). The information contained herein is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the governments of Canada, Mexico or the United States of America. Reproduction of this document in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes may be made without special permission from the CEC Secretariat, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. The CEC would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication or material that uses this document as a source. Except where otherwise noted, this work is protected under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial–No Derivative Works License. © Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 2017 Publication Details Publication type: Project Publication Publication date: May 2017 Original language: English Review and quality assurance procedures: Final Party review: April 2017 QA313 Project: 2015-2016/Strengthening conservation and sustainable production of selected CITES Appendix II species in North America ISBN: 978-2-89700-208-4 (e-version); 978-2-89700-209-1 (print) Disponible en français -

ARAV Conservation

Section 30 ARAV Conservation Anneliese Strunk, DVM, DABVP (Avian); Tony Qureishi, DVM Moderators Follicle-Stimulating-Hormone-Induced Mating: Behavior and Histologic Changes in a Pair of Ocellated Lizards (Timon lepidus) Emanuele Lubian, DVM, GPCert(ExAP), Alessandro Vetere, DVM, Massimo Millefanti, DVM Session #005 Affliation: From Ambulatorio veterinario, via Galvani 42, Gaggiano, 20083, Italy. Abstract: This report describes a clinical approach and observed behavioral and histologic changes in a pair of Timon lepidus treated with follitropin alfa to induce breeding. Hormonal treatments are very rarely used to treat infertility in reptiles; otherwise in other species as well as in human medicine they, as artifcial insemination, are one of the most important solutions. The conclusion of this case report suggests a possible therapy for this problem. A pair of 3-year-old ocellated lizards (Timon lepidus) was evaluated for mating reluctance. After hibernation, the male was introduced into the female’s cage. The female immediately showed aggresive behavior toward the male. This same procedure was successively tried without any positive results. After multiple failed attempts and about 1 month after the end of hibernation, we initiated therapy. We used follitropin alfa, a hormone identical to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), obtained by DNA recombination of ovarian cells of the Chinese hamster (Cricetulus griseus). Follitropin alfa often is used in human medicine in patients afficted by hypogonadism or insuffcient plasma levels of gonadotropins. By the eleventh day of treatment, the owner observed a behavior change that could be referred to as reproductive activity of the male. The female did not exhibit any aggressive behavior toward the male. -

Gopherus Berlandieri (Agassiz)

213.1 REPTILIA: TESTUDINES: TESTUDINIDAE GOPHERUS BERLANDIERI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. (1969), Ernst and Barbour (1972), and Rose and Judd (1975). Data on distribution and the influence of the Balcones escarpment are AUFFENBERG,WALTER,ANDRICHARDFRANZ. 1978. Gopherus presented by Smith and Buechner (1947); courtship and breeding berlandieri are discussed by Hamilton (1944), Woodbury (1952), and Weaver (1970); righting reflex by Ashe (1970); behavior by Eglis (1962); coprophagy by Mares (1971); eggs and nesting by Strecker (1928), Gopherus berlandieri (Agassiz) Grant (1960), Sabath (1960), Brown (1964), and Auffenberg and Texas tortoise Weaver (1969); burrow and shelter utilization by Auffenberg and Weaver (1969); visual cliff perception by Patterson (1971); ther• Xerobates berlandieri Agassiz, 1857:447. Type-locality not spec• mal characteristics by Hutchison et al. (1966); cranial circulatory ified by Agassiz, given as "Brownsville, Cameron County, system by McDowell (1961); buoyancy by Patterson (1973); hemo• Texas," by Schmidt (1953:105), and as "Lower Rio Grande globin structure by Sullivan and Riggs (1967a, 1967b, 1967c), ser• (restricted to Brownsville, Texas), Texas," by Cochran ology by Frair (1964) and Helmy et al. (1969); mental gland se• (1961:236). The earliest specific locality is "Lower Rio cretions by Rose et al. (1969); ureogenesis by Baze and Horne Grande" (Baird, 1859:4). Two syntypes, U.S. Nat. Mus. 60 (1970); regulation of ureabiosynthesis enzymes by Mora et al. (2), collected by J. L. Berlandier (not examined by authors). (1965); parasites by Schad et al. (1964); cutaneous myiasis by Testudo berlandieri: Cope, 1880:13. Neck (1977); aestivation and thermoregulation by Voigt and John• G[opherus].