Geochelone Platynota (Blyth 1863) – Burmese Star Tortoise, Kye Leik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texas Tortoise

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE TEXAS TORTOISE, CONTACT: ∙ TPWD: 800-792-1112 OF THE FOUR SPECIES OF TORTOISES FOUND http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/ IN NORTH AMERICA, THE TEXAS TORTOISE TEXAS ∙ Gulf Coast Turtle and Tortoise Society: IS THE ONLY ONE FOUND IN TEXAS. 866-994-2887 http://www.gctts.org/ THE TEXAS TORTOISE CAN BE FOUND IF YOU FIND A TEXAS TORTOISE THROUGHOUT SOUTHERN TEXAS AS WELL AS (OUT OF HABITAT), CONTACT: TORTOISE ∙ TPWD Law Enforcement TORTOISE NORTHEASTERN MEXICO. ∙ Permitted rehabbers in your area http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/huntwild/wild/rehab/ GOPHERUS BERLANDIERI UNFORTUNATELY EVERYTHING THERE ARE MANY THREATS YOU NEED TO KNOW TO THE SURVIVAL OF THE ABOUT THE STATE’S ONLY TEXAS TORTOISE: NATIVE TORTOISE HABITAT LOSS | ILLEGAL COLLECTION & THE THREATS IT FACES ROADSIDE MORTALITIES | PREDATION EXOTIC PATHOGENS TexasTortoise_brochure_V3.indd 1 3/28/12 12:12 PM COUNTIES WHERE THE TEXAS TORTOISE IS LISTED THE TEXAS TORTOISE (Gopherus berlandieri) is the smallest of the North American tortoises, reaching a shell length of about TEXAS TORTOISE AS A THREATENED SPECIES 8½ inches (22cm). The Texas tortoise can be distinguished CAN BE FOUND IN THE STATE OF TEXAS AND THEREFORE from other turtles found in Texas by its cylindrical and IS PROTECTED BY STATE LAW. columnar hind legs and by the yellow-orange scutes (plates) on its carapace (upper shell). IT IS ILLEGAL TO COLLECT, POSSESS, OR HARM A TEXAS TORTOISE. PENALTIES CAN INCLUDE PAYING A FINE OF Aransas, Atascosa, Bee, Bexar, Brewster, $273.50 PER TORTOISE. Brooks, Calhoun, Cameron, De Witt, Dimmit, Duval, Edwards, Frio, Goliad, Gonzales, Guadalupe, Hidalgo, Jackson, Jim Hogg, Jim Wells, Karnes, Kenedy, Kinney, Kleberg, La Salle, Lavaca, Live Oak, Matagorda, Maverick, McMullen, Medina, Nueces, WHAT SHOULD YOU Refugio, San Patricio, Starr, Sutton, Terrell, Uvalde, Val Verde, Victoria, Webb, Willacy, DO IF YOU FIND A Wilson, Zapata, Zavala TEXAS TORTOISE? THE TEXAS TORTOISE IS THE SMALLEST IN THE WILD AN INDIVIDUAL TEXAS TORTOISE LEAVE IT ALONE. -

Chelonian Perivitelline Membrane-Bound Sperm Detection: a New Breeding Management Tool

Zoo Biology 35: 95–103 (2016) RESEARCH ARTICLE Chelonian Perivitelline Membrane-Bound Sperm Detection: A New Breeding Management Tool Kaitlin Croyle,1,2 Paul Gibbons,3 Christine Light,3 Eric Goode,3 Barbara Durrant,1 and Thomas Jensen1* 1San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, Escondido, California 2Department of Biological Sciences, California State University San Marcos, San Marcos, California 3Turtle Conservancy, New York, New York Perivitelline membrane (PVM)-bound sperm detection has recently been incorporated into avian breeding programs to assess egg fertility, confirm successful copulation, and to evaluate male reproductive status and pair compatibility. Due to the similarities between avian and chelonian egg structure and development, and because fertility determination in chelonian eggs lacking embryonic growth is equally challenging, PVM-bound sperm detection may also be a promising tool for the reproductive management of turtles and tortoises. This study is the first to successfully demonstrate the use of PVM-bound sperm detection in chelonian eggs. Recovered membranes were stained with Hoechst 33342 and examined for sperm presence using fluorescence microscopy. Sperm were positively identified for up to 206 days post-oviposition, following storage, diapause, and/or incubation, in 52 opportunistically collected eggs representing 12 species. However, advanced microbial infection frequently hindered the ability to detect membrane-bound sperm. Fertile Centrochelys sulcata, Manouria emys,andStigmochelys pardalis eggs were used to evaluate the impact of incubation and storage on the ability to detect sperm. Storage at À20°C or in formalin were found to be the best methods for egg preservation prior to sperm detection. Additionally, sperm-derived mtDNA was isolated and PCR amplified from Astrochelys radiata, C. -

Egyptian Tortoise (Testudo Kleinmanni)

EAZA Reptile Taxon Advisory Group Best Practice Guidelines for the Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) First edition, May 2019 Editors: Mark de Boer, Lotte Jansen & Job Stumpel EAZA Reptile TAG chair: Ivan Rehak, Prague Zoo. EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (May 2019) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA Reptile TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. EAZA Preamble Right from the very beginning it has been the concern of EAZA and the EEPs to encourage and promote the highest possible standards for husbandry of zoo and aquarium animals. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

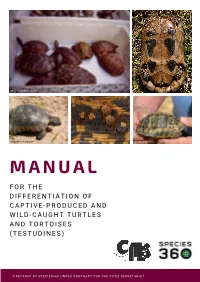

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Indian Star Tortoise Care

RVC Exotics Service Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street London NW1 0TU T: 0207 554 3528 F: 0207 388 8124 www.rvc.ac.uk/BSAH INDIAN STAR TORTOISE CARE Indian star tortoises originate from the semi-arid dry grasslands of Indian subcontinent. They can be easily recognised by the distinctive star pattern on their bumpy carapace. Star tortoises are very sensitive to their environmental conditions and so not recommended for novice tortoise owners. It is important to note that these tortoises do not hibernate. HOUSING • Tortoises make poor vivarium subjects. Ideally a floor pen or tortoise table should be created. This needs to have solid sides (1 foot high) for most tortoises. Many are made out of wood or plastic. A large an area as possible should be provided, but as the size increases extra basking sites will need to be provided. For a small juvenile at least 90 cm (3 feet) long x 30 cm (1 foot) wide is recommended. This is required to enable a thermal gradient to be created along the length of the tank (hot to cold). • Hides are required to provide some security. Artificial plants, cardboard boxes, plant pots, logs or commercially available hides can be used. They should be placed both at the warm and cooler ends of the tank. • Substrates suitable for housing tortoises include newspaper, Astroturf, and some of the commercially available substrates. Natural substrate such as soil may also be used to allow for digging. It is important that the substrates either cannot be eaten, or if they are, do not cause blockages as this can prove fatal. -

Aldabrachelys Arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold's Giant Tortoise

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTestudinidae of the IUCN/SSC — AldabrachelysTortoise and Freshwater arnoldi Turtle Specialist Group 028.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.028.arnoldi.v1.2009 © 2009 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 18 October 2009 Aldabrachelys arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold’s Giant Tortoise JUSTIN GERLACH 1 1133 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge CB1 7BX, United Kingdom [[email protected]] SUMMARY . – Arnold’s giant tortoise, Aldabrachelys arnoldi (= Dipsochelys arnoldi) (Family Testudinidae), from the granitic Seychelles, is a controversial species possibly distinct from the Aldabra giant tortoise, A. gigantea (= D. dussumieri of some authors). The species is a morphologi- cally distinctive morphotype, but has so far not been genetically distinguishable from the Aldabra tortoise, and is considered synonymous with that species by many researchers. Captive reared juveniles suggest that there may be a genetic basis for the morphotype and more detailed genetic work is needed to elucidate these relationships. The species is the only living saddle-backed tortoise in the Seychelles islands. It was apparently extirpated from the wild in the 1800s and believed to be extinct until recently purportedly rediscovered in captivity. The current population of this morphotype is 23 adults, including 18 captive adult males on Mahé Island, 5 adults recently in- troduced to Silhouette Island, and one free-ranging female on Cousine Island. Successful captive breeding has produced 138 juveniles to date. -

(Geochelone Pardalis) on Farmland in the Nama-Karoo

THE STATUS AND ECOLOGY OF THE LEOPARD TORTOISE (GEOCHELONE PARDALIS) ON FARMLAND IN THE NAMA-KAROO MEGAN KAY McMASTER Submitted in fulfilment ofthe academic requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE School ofBotany and Zoology University ofNatal Pieterrnaritzburg March 2001 Preface The experimental work described in this dissertation was carried out in the School of Botany and Zoology, University ofNatal, Pietermaritzburg, from November 1997 to March 2001, under the supervision ofDr. Colleen T. Downs. This study is the original work ofthe author and has not been submitted in any form for any diploma or degree to another university. Where use has been made ofthe work of others, it is duly acknowledged in the text. Each chapter is written in the format ofthe journal it has been submitted to. ..fj~K'. Megan Kay McMaster Pietermaritzburg March 2001 11 This thesis is dedicated to myfather, the late Eric Ralph McMaster, for his constant encouragement and beliefin me, and to my brother, the late Gregory CIifton McMaster,for always making me smile. III Abstract The Family Testudinidae (Suborder Cryptodira) is represented by 40 species worldwide and reaches its greatest diversity in southern Africa, where 14 species occur (33%), ten of which are endemic to the subcontinent. Despite the strong representation ofterrestrial tortoise species in southern Africa, and the importance ofthe Karoo as a centre of endemism ofthese tortoise species, there is a paucity ofecological information for most tortoise species in South Africa. With chelonians being protected in < 15% ofall southern African reserves it is necessary to find out more about the ecological requirements, status, population dynamics and threats faced by South African tortoise species to enable the formulation ofeffective conservation measures. -

For Enumeration of This Part a Linear Sequence of Lycophytes and Ferns After Christenhusz, M

PTERIDOPHYTA For enumeration of this part A linear sequence of Lycophytes and Ferns after Christenhusz, M. J. M.; Zhang, X.C. & Schneider, H. (2011) has been followed Subclass: Lycopodiidae Beketov (1863). Order: Selaginellales (1874). Selaginellaceae Willkomm, Anleit. Stud. Bot. 2: 163. 1854; Prodr. FI. Hisp. 1(1): 14. 1861. SELAGINELLA P. Beauvois, Megasin Encycl. 9: 478. 1804. Selaginella monospora Spring, Mém. Acad. Roy. Sci. Belgique 24: 135. 1850; Monogr. Lyc. II:135. 1850; Alston, Bull. Fan. Mem. Inst. Biol. Bot. 5: 288, 1954; Alston, Proc. Nat. Inst. Sc. Ind. 11: 228. 1945; Reed, C.F., Ind. Sellaginellarum 160 – 161. 1966; Panigrahi et Dixit, Proc. Nat. Inst. Sc. Ind. 34B (4): 201, f.6. 1968; Kunio Iwatsuki in Hara, Fl. East. Himal. 3: 168. 1972; Ghosh et al., Pter. Fl. East. Ind. 1: 127. 2004. Selaginella gorvalensis Spring, Monogr. Lyc. II: 256. 1850; Bak, Handb. Fern Allies 107. 1887; Selaginella microclada Bak, Jour. Bot. 22: 246. 1884; Selaginella plumose var. monospora (Spring) Bak, Jour. Bot. 21:145. 1883; Selaginella semicordata sensu Burkill, Rec. Bot. Surv. Ind. 10: 228. 1925, non Spring. Plant up to 90 cm, main stem prostrate, rooting on all sides and at intervals, unequally tetragonal, main stem alternately branched 5 – 9 times, branching unequal, flexuous; leavesobscurely green, dimorphus, lateral leaves oblong to ovate-lanceolate, subacute, denticulate to serrulate at base. Spike short, quadrangular, sporophylls dimorphic, large sporophyls less than half as long as lateral leaves, oblong- lanceolate, obtuse, denticulate, small sporophylls dentate, ovate, acuminate. Fertile: October to January. Specimen Cited: Park, Rajib & AP Das 0521, dated 23. 07. -

Movement, Home Range and Habitat Use in Leopard Tortoises (Stigmochelys Pardalis) on Commercial

Movement, home range and habitat use in leopard tortoises (Stigmochelys pardalis) on commercial farmland in the semi-arid Karoo. Martyn Drabik-Hamshare Submitted in fulfilment of the academic requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Discipline of Ecological Sciences School of Life Sciences College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science University of KwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg Campus 2016 ii ABSTRACT Given the ever-increasing demand for resources due to an increasing human population, vast ranges of natural areas have undergone land use change, either due to urbanisation or production and exploitation of resources. In the semi-arid Karoo of southern Africa, natural lands have been converted to private commercial farmland, reducing habitat available for wildlife. Furthermore, conversion of land to energy production is increasing, with areas affected by the introduction of wind energy, solar energy, or hydraulic fracturing. Such widespread changes affects a wide range of animal and plant communities. Southern Africa hosts the highest diversity of tortoises (Family: Testudinidae), with up to 18 species present in sub-Saharan Africa, and 13 species within the borders of South Africa alone. Diversity culminates in the Karoo, whereby up to five species occur. Tortoises throughout the world are undergoing a crisis, with at least 80 % of the world’s species listed at ‘Vulnerable’ or above. Given the importance of many tortoise species to their environments and ecosystems— tortoises are important seed dispersers, whilst some species produce burrows used by numerous other taxa—comparatively little is known about certain aspects relating to their ecology: for example spatial ecology, habitat use and activity patterns. -

Major Creeper and Climber Weeds in India

TechnicalTechnical Bulletin Bulletin No. 13 No. 13 Major Creeper and Climber weeds in India V.C. Tyagi, R.P. Dubey, Subhash Chander and Anoop Kumar Rathore Hkk-d`-vuq-i-& [kjirokj vuqla/kku funs'kky;] tcyiqj ICAR - Directorate of Weed Research, Jabalpur ISO 9001 : 2015 Certified Correct citation Major Creeper and Climber Weeds in India, 2017. ICAR-Directorate of Weed Research, Jabalpur, 50 p. Published by Dr. P.K. Singh Director, ICAR - Directorate of Weed Research, Jabalpur Compiled and edited by V.C. Tyagi R.P. Dubey Subhash Chander Anoop Kumar Rathore Technical Assistance Sandeep Dhagat Year of publication March, 2017 Contact address ICAR - Directorate of Weed Research, Jabalpur (M.P.), India Phone : 0761-2353934, 2353101; Fax : 0761-2353129 Email: [email protected] Website : http://www.dwr.org.in Cover theme (a) (b) Photos of major creeper and climber weeds, viz. (a) Convolvulus arvensis, (b) Diplocyclos palmatus, (c) Lathyrus aphaca....................................................................... (c) PREFACE Weeds are plants which interfere in human activities and welfare. They are a problem not only in cropped lands but also in non-cropped areas, pastures, aquatic bodies, roadsides, parks etc. In agricultural crops, weeds may cause on an average 37% reduction in yields, whereas, in non-cropped areas they reduce the value of the land. Weeds can be of different types. The category of creeper or climber weeds has characteristics different than other weeds. These weeds are capable of creeping or climbing as they have special structures such as tendrils, hooks, twining stems and leaves etc. In agricultural crops they can climb up the crop plants, shade them and compete for resources reducing the yields.