Status of the Species and Its Critical Habitat- Rangewide: February 9, 2012 1. Desert Tortoise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egyptian Tortoise (Testudo Kleinmanni)

EAZA Reptile Taxon Advisory Group Best Practice Guidelines for the Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) First edition, May 2019 Editors: Mark de Boer, Lotte Jansen & Job Stumpel EAZA Reptile TAG chair: Ivan Rehak, Prague Zoo. EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (May 2019) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA Reptile TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. EAZA Preamble Right from the very beginning it has been the concern of EAZA and the EEPs to encourage and promote the highest possible standards for husbandry of zoo and aquarium animals. -

Anthropogenic Disturbance and Mojave Desert Tortoise (Gopherus Agassizii) Genetic Connectivity

University of Nevada, Reno Connecting the Plots: Anthropogenic Disturbance and Mojave Desert Tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) Genetic Connectivity A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Geography By Kirsten Erika Dutcher Dr. Jill S. Heaton, Dissertation Advisor May 2020 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by KIRSTEN ERIKA DUTCHER entitled Connecting the Plots: Anthropogenic Disturbance and Mojave Desert Tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) Genetic Connectivity be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Jill S. Heaton, Ph.D. Advisor Kenneth E. Nussear, Ph.D. Committee Member Scott D. Bassett, Ph.D. Committee Member Amy G. Vandergast, Ph.D. Committee Member Marjorie D. Matocq, Ph.D. Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean Graduate School May, 2020 i ABSTRACT Habitat disturbance impedes connectivity for native populations by altering natural movement patterns, significantly increasing the risk of population decline. The Mojave Desert historically exhibited high ecological connectivity, but human presence has increased recently, as has habitat disturbance. Human land use primarily occurs in Mojave desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) habitat posing risks to the federally threatened species, which has declined as a result. As threats intensify, so does the need to protect tortoise habitat and connectivity. Functional corridors require appropriate habitat amounts and population densities, as individuals may need time to achieve connectivity and find mates. Developments in tortoise habitat have not been well studied, and understanding the relationship between barriers, corridors, population density, and gene flow is an important step towards species recovery. -

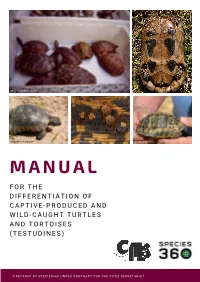

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Providence Mountains State Recreation Area 38200 Essex Road Or P.O

Our Mission Providence The mission of California State Parks is to provide for the health, inspiration and In the middle of the education of the people of California by helping Mountains to preserve the state’s extraordinary biological Mojave Desert, Jack and diversity, protecting its most valued natural and State Recreation Area cultural resources, and creating opportunities Ida Mitchell shared with for high-quality outdoor recreation. thousands of fortunate visitors the cool beauty of the caverns’ magnificent “draperies” and “coral California State Parks supports equal access. pipes” formations. Prior to arrival, visitors with disabilities who need assistance should contact the park at (760) 928-2586. If you need this publication in an alternate format, contact [email protected]. CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 For information call: (800) 777-0369 (916) 653-6995, outside the U.S. 711, TTY relay service www.parks.ca.gov Providence Mountains State Recreation Area 38200 Essex Road or P.O. Box 1 Essex, CA 92332 • (760) 928-2586 © 2010 California State Parks (Rev. 2017) V isitors to Providence Mountains State that left abundant shell-covered organisms Recreation Area are greeted by the sight on the sea floor. of jagged slopes of gray limestone, topped The shells and plant materials that settled by volcanic peaks of red rhyolite. Located on the sea bottom eventually became on the eastern slope of the Providence limestone. As the restless land heaved Mountains Range, the park lies within the upward, these formations were pushed boundaries of the 1.6-million acre Mojave above the level of the former ocean bed. -

Mineral Resources and Mineral Resource Potential of the Saline Valley and Lower Saline Wilderness Study Areas Inyo County, California

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Mineral resources and mineral resource potential of the Saline Valley and Lower Saline Wilderness Study Areas Inyo County, California Chester T. Wrucke, Sherman P. Marsh, Gary L. Raines, R. Scott Werschky, Richard J. Blakely, and Donald B. Hoover U.S. Geological Survey and Edward L. McHugh, Clay ton M. Rumsey, Richard S. Gaps, and J. Douglas Causey U.S. Bureau of Mines U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 84-560 Prepared by U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Bureau of Mines for U.S. Bureau of Land Management This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. 1984 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Mineral resources and mineral resource potential of the Saline Valley and Lower Saline Wilderness Study Areas Inyo County, California by Chester T. Wrucke, Sherman P. Marsh, Gary L. Raines, R. Scott Werschky, Richard J. Blakely, and Donald B. Hoover U.S. Geological Survey and Edward L. McHugh, Clayton M. Rumsey, Richard S. Gaps, and J. Douglas Causey U.S. Bureau of Mines U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 84-560 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. 1984 ILLUSTRATIONS Plate 1. Mineral resource potential map of the Saline Valley and Lower Saline Wilderness Study Areas, Inyo County, California................................ In pocket Figure 1. Map showing location of Saline Valley and Lower Saline Wilderness Study Areas, California.............. 39 2. -

Interest and the Panamint Shoshone (E.G., Voegelin 1938; Zigmond 1938; and Kelly 1934)

109 VyI. NOTES ON BOUNDARIES AND CULTURE OF THE PANAMINT SHOSHONE AND OWENS VALLEY PAIUTE * Gordon L. Grosscup Boundary of the Panamint The Panamint Shoshone, also referred to as the Panamint, Koso (Coso) and Shoshone of eastern California, lived in that portion of the Basin and Range Province which extends from the Sierra Nevadas on the west to the Amargosa Desert of eastern Nevada on the east, and from Owens Valley and Fish Lake Valley in the north to an ill- defined boundary in the south shared with Southern Paiute groups. These boundaries will be discussed below. Previous attempts to define the Panamint Shoshone boundary have been made by Kroeber (1925), Steward (1933, 1937, 1938, 1939 and 1941) and Driver (1937). Others, who have worked with some of the groups which border the Panamint Shoshone, have something to say about the common boundary between the group of their special interest and the Panamint Shoshone (e.g., Voegelin 1938; Zigmond 1938; and Kelly 1934). Kroeber (1925: 589-560) wrote: "The territory of the westernmost member of this group [the Shoshone], our Koso, who form as it were the head of a serpent that curves across the map for 1, 500 miles, is one of the largest of any Californian people. It was also perhaps the most thinly populated, and one of the least defined. If there were boundaries, they are not known. To the west the crest of the Sierra has been assumed as the limit of the Koso toward the Tubatulabal. On the north were the eastern Mono of Owens River. -

Birds of the California Desert

BIRDS OF THE CALIFORNIA DESERT A. Sidney England and William F. Laudenslayer, Jr. i INTRODUCTION i \ 1 The term, "California desert", as used herein, refers to a politically defined region, most of i which is included in the California Desert Conservation Area (CDCA) designated by the Federal Land ; and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA). Of the 25 million acres in the CDCA, about one-half are i public lands, most of which are managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) according to the "980 P California Desert Conservation Area Plan mandated by FLPMA. The California desert encompasses those portions of the Great Basin Desert (east of the White and lnyo Mountains and A south of the California-Nevada border), the Mojave Desert, and the Colorado Desert which occur " within California; it does not include areas of riparian, aquatic, urban, and agricultural habitats . adjacent to the Colorado River. (Also see chapters on Geology by Norris and Bioclimatology by E3irdsI4 are the most conspicuous vertebrates found in the California deserts. Records exist for at least 425 species (Garrett and Dunn 1981) from 18 orders and 55 families. These counts far exceed those for mammals, reptiles, amphibians and fish, and they are similar to totals for the entire state -- 542 species from 20 orders and 65 families (Laudenslayer and Grenfell 1983). These figures may seem surprisingly similar considering the harsh, arid climates often believed characteristic of I desert environments. However, habiiats found in the California desert range from open water and h marshes at the Salton Sea to pinyon-juniper woodland and limber pinelbristlecone pine forests on a few mountain ranges. -

Understanding the Source of Water for Selected Springs Within Mojave Trails National Monument, California

ENVIRONMENTAL FORENSICS, 2018 VOL. 19, NO. 2, 99–111 https://doi.org/10.1080/15275922.2018.1448909 Understanding the source of water for selected springs within Mojave Trails National Monument, California Andy Zdon, PG, CHg, CEGa, M. Lee Davisson, PGb and Adam H. Love, Ph.D.c aTechnical Director – Water Resources, PARTNER ENGINEERING AND SCIENCE, INC., Santa Ana, CA, Sacramento, CA; bML Davisson & Associates, Inc., Livermore, CA; cVice President/Principal Scientist, Roux Associates, Inc., Oakland, CA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS While water sources that sustain many of the springs in the Mojave Desert have been poorly Water resources; clipper understood, the desert ecosystem can be highly dependent on such resources. This evaluation mountains; bonanza spring; updates the water resource forensics of Bonanza Spring, the largest spring in the southeastern groundwater; forensics; Mojave Desert. The source of spring flow at Bonanza Spring was evaluated through an integration isotopes of published geologic maps, measured groundwater levels, water quality chemistry, and isotope data compiled from both published sources and new samples collected for water chemistry and isotopic composition. The results indicate that Bonanza Spring has a regional water source, in hydraulic communication with basin fill aquifer systems. Neighboring Lower Bonanza Spring appears to primarily be a downstream manifestation of surfacing water originally discharged from the Bonanza Spring source. Whereas other springs in the area, Hummingbird, Chuckwalla, and Teresa Springs, each appear to be locally sourced as “perched” springs. These conclusions have important implications for managing activities that have the potential to impact the desert ecosystem. Introduction above Bonanza Spring. Identification of future impacts General information and data regarding springs in the from water resource utilization becomes problematic if Mojave Desert are sparse, and many of these springs are initial baseline conditions are unknown or poorly under- not well understood. -

Inferences Regarding Aboriginal Hunting Behavior in the Saline Valley, Inyo County, California

Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Vol. 2, No. I, pp. 60-79(1980). Inferences Regarding Aboriginal Hunting Behavior in the Saline Valley, Inyo County, California RICHARD A. BROOK HE documented use of stone "hunting a member of the 1861 Boundary Survey Party Tblinds" behind which marksmen hid them reconnoitering the Death Valley region. The selves "ve'/7//-6'o?m-e"i (Baillie-Grohman 1884: chronicler observed: 168) waiting for sheep to be driven along trails, can be found in the writings of a number of . curious structures ... on the tops of early historians (Baillie-Grohman 1884; round bald hills, a short distance to the Spears 1892; Muir 1901; Bailey 1940). Recent northwest of the springs, being low walls of archaeological discoveries of rock features loose stones curved in the shape of a demi lune, about ten feet in length and about believed to be hunting blinds at the Upper three feet high . , . , There were twenty or Warm Springs (Fig. I) in Saline Valley, Inyo thirty of them [Woodward 1961:49], County, California, provide a basis to substan tiate, build upon, and evaluate these observa This paper discusses a series of 60 such piled- tions and the ethnographic descriptions of up boulder features recorded within a I km.^ hunting in the Great Basin (Steward 1933, area at Upper Warm Springs (Fig. 2). 1938, 1941; Driver 1937; Voegelin 1938; The same chronicler offered some tentative Stewart 1941). An examination of these explanations as to their function: features, their location, orientation, and asso ciations in -

Breeding Avifaunas of the New York Mountains and Kingston Range: Islands of Conifers in the Mojave Desert of California

BREEDING AVIFAUNAS OF THE NEW YORK MOUNTAINS AND KINGSTON RANGE: ISLANDS OF CONIFERS IN THE MOJAVE DESERT OF CALIFORNIA STEVEN W. CARDIFF and J.V. REMSEN, Jr., Museum of Zoologyand Depart- ment of Zoology,Louisiana State University,Baton Rouge, Louisiana70893-3216 Quantificationof speciesturnover rates on islandsin the context of the equilibriumtheory of island biogeography(MacArthur and Wilson 1967) dependson accurateinventories of the biotataken at appropriateintervals in time. Inaccuratehistorical data concerningspecies composition is a sourceof error that must be avoided when calculatingturnover rates (Lynch and Johnson1974). Johnson's(1974) analysisof historicalchanges in species compositionand abundanceexemplifies the importanceof sound avifaunal inventoriesfor later comparison. In this paper, we present data to provide future researchers with a baseline from which to calculate turnover rates for the breeding avifaunas of two conifer "islands" in the Mojave Desert in California. Islandbiogeography of isolatedmountain ranges forming conifer "islands" in the Great Basin has been studiedby Brown (1971, 1978) for mammals and Johnson(1975) for birds.An analysisof breedingbird turnoverrates for a coniferisland in the Mojave Desert(Clark Mountain, California)is in prog- ress (N.K. Johnson pers. comm.). Detailed and accurate surveysof the breedingavifaunas of the Sheep and Springranges of southwesternNevada (Johnson 1965) and the Providence Mountains, San Bernardino Co., California (Johnson et al. 1948) provide data from other Mojave Desert rangesfor comparisonwith data we presentbelow. STUDY AREAS New York Mountains. The New York Mountains extend from about 14 km west of Cima east to the Nevada border in extreme eastern San Bernardino Co., California. The highestpoint, New York Peak (7532 ft--2296 m), is 39.5 km southeastof Clark Mountain (7929 ft = 2417 m) and 118 km south of CharlestonPeak (11,919 ft=3633 m) in the Spring Mountainsof Nevada. -

Mojave National Preserve Management Plan for Developed

Mojave National Preserve—Management Plan for Developed Water Resources CHAPTER 3: AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT Introduction This chapter describes the unique factors that influence water resource management in the Preserve and the resources that could be affected by the implementation of any of the alternatives described in Chapter 2: Alternatives. The resource descriptions provided in this chapter serve as a baseline to compare the potential effects of the management actions proposed in the alternatives. The following resource topics are described in this chapter: • Environmental Setting • Cultural Resources • Water Resources • Wilderness Character • Wildlife Environmental setting and water resources are important for context and are foundational for water resource management, but are not resources that are analyzed for effects. Resource issues that were considered and dismissed from further analysis are listed in Chapter 1: Purpose of and Need for Action and are not discussed further in this EA. A description of the effects of the proposed alternatives on wildlife, cultural resources, and wilderness character is presented in Chapter 4: Environmental Consequences. Environmental Setting The Preserve includes an ecologically diverse yet fragile desert ecosystem consisting of vegetative attributes that are unique to the Mojave Desert, as well as components of the Great Basin and Sonoran Deserts. Topography The topography of the Preserve is characteristic of the mountain and basin physiographic pattern, with tall mountain ranges separated by corresponding valleys filled with alluvial sediments. Primary mountain ranges in the Preserve, from west to east, include the Granite, Kelso, Providence, Clark, New York, and Piute Mountains. Major alluvial valleys include Soda Lake (dry lake bed), Shadow Valley, Ivanpah Valley, Lanfair Valley, and Fenner Valley.