Development of the Turtle Plastron, the Order-Defining Skeletal Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACTS 44Th Annual Meeting and Symposium Tucson, Arizona February 21–23, 2019

ABSTRACTS 44th Annual Meeting and Symposium Tucson, Arizona February 21–23, 2019 FORTY-FOURTH ANNUAL MEETING AND SYMPOSIUM THE DESERT TORTOISE COUNCIL TUCSON, AZ February 21–23, 2019 ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS AND POSTERS (Abstracts arranged alphabetically by last name of first author) *Speaker, if not the first author listed Long-term Data Collection and Trends of a 130-Acre High Desert Riparian and Upland Preserve in Northwestern Mohave County, Arizona Julie Alpert and Robert Faught Willow Creek Environmental Consulting, LLC, 15857 E. Silver Springs Road, Kingman, Arizona 86401, USA.Phone: 928-692-6501. Email: [email protected] The Willow Creek Riparian Preserve (Preserve) is a privately owned 130-acre site located 30 miles east of Kingman, Arizona. The Preserve was formally established in 2007 with the purchase of 10-acres and an agreement with the eastern adjoining private landowner to add an additional 120-acres. The Preserve location was unfenced and wholly accessible by livestock, off-road vehicle use, and hunting. In October of 2008 the Preserve was fenced with volunteer efforts from the local Rotary Club and Boy Scout Troop 66. Additional financial assistance came through a large discount in the cost of fencing materials from Kingman Ace Hardware. A total of 0.5-linear mile of new wildlife friendly fencing (barbless top wire and 18-inches above-ground bottom wire) was installed along the south and west sides and connected to existing Arizona State Lands cattle allotment fencing. Baseline and on-going studies and data collection have occurred since 2004. These have included small mammal live trapping; chiropteran surveys with the use of Anabat; migratory, breeding, and winter avian surveys; amphibian and reptile surveys; deployment of game cameras; animal track and sign identification and movement patterns; vegetation and plant surveys; and a wetland delineation. -

Sea Turtle Activity Book

Sea Turtle Adventures II The adventure continues... An Activity Book for All Ages Welcome to Sarasota County! The beautiful beaches and surrounding waters of Sarasota REMOVE OBSTACLES: Turtles can easily become trapped County provide critical habitat for important populations in beach furniture, recreational equipment, tents and of threatened and endangered sea turtles. We are honored toys, or fall into deep holes in the sand. You can provide that many sea turtles make Sarasota County their home a more natural and safe shoreline for the turtles to nest year-round, while other sea turtles migrate to our beaches by removing all items from the beach each night. Also, from hundreds of miles away to find mates and nest. remember to leave the beach as you found it by knocking down sandcastles, filling in holes, and picking up garbage, Each year between May 1 and Oct. 31, adult female sea especially plastics, which can be mistaken for food by turtles crawl out of the Gulf of Mexico to lay approximately sea turtles. 100 eggs in a sandy nest on our beaches. The clutch incubates for almost two months until the hatchlings We hope you enjoy learning more about sea turtles in this emerge one night and make their way to the Gulf. During activity book. Thank you for sharing the shore and helping this special time of year, there are many things you can do to make our beaches more turtle-friendly! to help and protect these magnificent animals. Sincerely, LIMIT LIGHTING: Lights on the beach confuse and disorient Your Friends at Sarasota County sea turtles. -

Loggerhead Sea Turtle

Loggerhead Sea Turtle Description: The Loggerhead Sea Turtle is named for its large head and blunt jaw. This huge sea turtle can grow to 800 pounds (though the average turtle is about 200 pounds) and three and a half feet in length. It is the largest hard-shelled turtle in the world. The carapace (shell) and flippers are reddish brown and the plastron (lower shell) is yellowish. The carapace has five lateral scutes and five central scutes. Scutes are hexagonal sections of the carapace. Underparts are white or whitish. These incredible turtles have powerful flippers that can propel them through the water at speeds of up to 16 miles per hour. The Loggerhead Sea Turtle has a life span of up to 50 years in the wild. Habitat/Range: The seafaring Loggerhead Sea Turtle is found throughout the world's tropical oceans. They are also found in temperate waters in search of food and in migration. Breeding populations exist in many locales including the Atlantic coast of the United States (from North Carolina to Florida), numerous Caribbean islands, Central America, the Mediterranean Sea, and Africa. Diet: Loggerhead Sea Turtles consume fish, crustaceans, mollusks, crabs, and jellyfish, They use their powerful jaws to crush prey. These turtles often ingest stray plastic bags which are mistaken for jellyfish and which cause potentially fatal complications. Nesting: The Female Loggerhead Sea Turtle normally lays her eggs on the same beach in which she was born. It may take up to 30 years before these turtles reach reproductive age. In June or July, females will emerge from the ocean and dig a hole in the sand. -

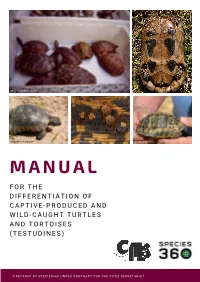

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The First Challenge Walking with Miskwaadesi the First Challenge THIRTEEN MOONS on a TURTLE’S BACK

1. THIRTEEN MOONS ON A TURTLE’S BACK THE FIRST CHALLENGE WALKING WITH MISKWAADESI THE FIRST CHALLENGE THIRTEEN MOONS ON A TURTLE’S BACK Who is Miskwaadesi and what does she need? How important is the Turtle to the people of the world? Can you describe the year in your language or culture according to the 13 moons? Will you accept Miskwaadesi’s challenges and help to make your community and your wetland world a healthier place for everyone and everything? “..come and walk in my footsteps. Bring your grandchildren and great grandchildren, and learn about me and my clan brothers and sisters. Will you help me find a safe and healthy place for my clan brothers and sisters to live? “ “Will you tell the people that everyone needs to work together to make our space a healthy one again?” Miskwaadesi’s 1st challenge. 23 EXPECTATIONS PRACTICING THE LEARNING | FOLLOWING THE FOOTSTEPS TITLE OF ACTIVITY ONTARIO CURRICULUM EXPECTATION WORKSHEET Introduction to Miskwaadesi’s 4e4, 4e5, 4e26 1a - 13 challenges challenges Turtles of the World 4z47, 4z35 1b - Turtles of the World DEMONSTRATING THE LEARNING | MAKING OUR OWN FOOTSTEPS TITLE OF ACTIVITY ONTARIO CURRICULUM EXPECTATION WORKSHEET A Year of the Turtle - 4a43, 4a44, 4a45 Calendar 13 moons Journal Reflection 4a43 Cover page Reflection no.1 4e56 ONE STEP MORE (individual student optional adventures in learning) 1. Research traditional teachings and stories about turtles 2. Tortoises of the World Miskwaadesi, calendar, challenge, tortoise, teaching, WORD WALL: Pleiades, symbol, emblem, 24 LINKS TO OTHER CURRICULUM 1st CHALLENGE Ways of Knowing Guide -– Relationship – the Sky World pg 75 http://www.torontozoo.com/pdfs/Stewardship_Guide.pdf Turtle Curriculum http://www.torontozoo.com/adoptapond/turtleCurriculum.asp 25 KOKOM ANNIE’S JOURNAL THE STORY BEGINS… “…Ahniin my grandchildren, Are you coming to spend the summer with me and your cousins here at Wasauksing? I need your help with a special project. -

Eastern Snake-Necked Turtle

Husbandry Manual for Eastern Snake-Necked Turtle Chelodina longicollis Reptilia: Chelidae Image Courtesy of Jacki Salkeld Author: Brendan Mark Host Date of Preparation: 04/06/06 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE - Richmond Course Name and Number: 1068 Certificate 3 - Captive Animals Lecturers: Graeme Phipps/Andrew Titmuss/ Jacki Salkeld CONTENTS 1. Introduction 4 2. Taxonomy 5 2.1 Nomenclature 5 2.2 Subspecies 5 2.3 Synonyms 5 2.4 Other Common Names 5 3. Natural History 6 3.1 Morphometrics 6 3.1.1 Mass and Basic Body Measurements 6 3.1.2 Sexual Dimorphism 6 3.1.3 Distinguishing Features 7 3.2 Distribution and Habitat 7 3.3 Conservation Status 8 3.4 Diet in the Wild 8 3.5 Longevity 8 3.5.1 In the Wild 8 3.5.2 In Captivity 8 3.5.3 Techniques Used to Determine Age in Adults 9 4. Housing Requirements 10 4.1 Exhibit/Enclosure Design 10 4.2 Holding Area Design 10 4.3 Spatial Requirements 11 4.4 Position of Enclosures 11 4.5 Weather Protection 11 4.6 Temperature Requirements 12 4.7 Substrate 12 4.8 Nestboxes and/or Bedding Material 12 4.9 Enclosure Furnishings 12 5. General Husbandry 13 5.1 Hygiene and Cleaning 13 5.2 Record Keeping 13 5.3 Methods of Identification 13 5.4 Routine Data Collection 13 6. Feeding Requirements 14 6.1 Captive Diet 14 6.2 Supplements 15 6.3 Presentation of Food 15 1 7. Handling and Transport 16 7.1 Timing of Capture and Handling 16 7.2 Capture and Restraint Techniques 16 7.3 Weighing and Examination 17 7.4 Release 17 7.5 Transport Requirements 18 7.5.1 Box Design 18 7.5.2 Furnishings 19 7.5.3 Water and Food 19 7.5.4 Animals Per Box 19 7.5.5 Timing of Transportation 19 7.5.6 Release from Box 19 8. -

A Unified Anatomy Ontology of the Vertebrate Skeletal System

A Unified Anatomy Ontology of the Vertebrate Skeletal System Wasila M. Dahdul1,2*, James P. Balhoff2,3, David C. Blackburn4, Alexander D. Diehl5, Melissa A. Haendel6, Brian K. Hall7, Hilmar Lapp2, John G. Lundberg8, Christopher J. Mungall9, Martin Ringwald10, Erik Segerdell6, Ceri E. Van Slyke11, Matthew K. Vickaryous12, Monte Westerfield11,13, Paula M. Mabee1 1 Department of Biology, University of South Dakota, Vermillion, South Dakota, United States of America, 2 National Evolutionary Synthesis Center, Durham, North Carolina, United States of America, 3 Department of Biology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States of America, 4 Department of Vertebrate Zoology and Anthropology, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, California, United States of America, 5 The Jacobs Neurological Institute, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York, United States of America, 6 Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon, United States of America, 7 Department of Biology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, 8 Department of Ichthyology, The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America, 9 Genomics Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California, United States of America, 10 The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine, United States of America, 11 Zebrafish Information Network, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon, United States of America, 12 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Guelph, -

Comparative Bone Histology of the Turtle Shell (Carapace and Plastron)

Comparative bone histology of the turtle shell (carapace and plastron): implications for turtle systematics, functional morphology and turtle origins Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades (Dr. rer. nat.) der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn Vorgelegt von Dipl. Geol. Torsten Michael Scheyer aus Mannheim-Neckarau Bonn, 2007 Angefertigt mit Genehmigung der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn 1 Referent: PD Dr. P. Martin Sander 2 Referent: Prof. Dr. Thomas Martin Tag der Promotion: 14. August 2007 Diese Dissertation ist 2007 auf dem Hochschulschriftenserver der ULB Bonn http://hss.ulb.uni-bonn.de/diss_online elektronisch publiziert. Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Januar 2007 Institut für Paläontologie Nussallee 8 53115 Bonn Dipl.-Geol. Torsten M. Scheyer Erklärung Hiermit erkläre ich an Eides statt, dass ich für meine Promotion keine anderen als die angegebenen Hilfsmittel benutzt habe, und dass die inhaltlich und wörtlich aus anderen Werken entnommenen Stellen und Zitate als solche gekennzeichnet sind. Torsten Scheyer Zusammenfassung—Die Knochenhistologie von Schildkrötenpanzern liefert wertvolle Ergebnisse zur Osteoderm- und Panzergenese, zur Rekonstruktion von fossilen Weichgeweben, zu phylogenetischen Hypothesen und zu funktionellen Aspekten des Schildkrötenpanzers, wobei Carapax und das Plastron generell ähnliche Ergebnisse zeigen. Neben intrinsischen, physiologischen Faktoren wird die -

The Diapsid Origin of Turtles

THE DIAPSID ORIGIN OF TURTLES Mrs. Basawarajeshwari Indur Dept of Zoology, Sharnbasva University, Kalaburagi. A B S T R A C T The origin of turtles has been a persistent unresolved problem involving unsettled questions in embryology, morphology, and paleontology. New fossil taxa from the early Late Triassic of China (Odontochelys) and the Late Middle Triassic of Germany (Pappochelys) now add to the understanding of (i) the evolutionary origin of the turtle shell, (ii) the ancestral structural pattern of the turtle skull, and (iii) the phylogenetic position of Testudines. As has long been postulated on the basis of molecular data, turtles evolved from diapsid reptiles and are more closely related to extant diapsids than to parareptiles, which had been suggested as stem group by some paleontologists. The turtle cranium with its secondarily closed temporal region represents a derived rather than a primitive condition and the plastron partially evolved through the fusion of gastralia Key word –Carapace, Plastron, Reptiles, Turtle origins I.INTRODUCTION The origin and early evolution of turtles has been a longstanding problem in vertebrate morphology and phylogeny (Rieppel and Reisz, 1999). The unique composition of the turtle shell as well as the closed (anapsid) architecture of the skull had been controversially debated issues for more than a century. The lack of fossils documenting plausible stem taxa predating the Late Triassic had long formed a major obstacle in this context. Until recently, the geologically oldest and most primitive stem turtles reached back only to the later part of the Late Triassic, whereas it was long thought that the turtle clade likely diverged from other reptiles already during the Permian. -

The Integumentary Skeleton of Tetrapods: Origin, Evolution, and Development Matthew K

J. Anat. (2009) 214, pp441–464 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.01043.x REVIEWBlackwell Publishing Ltd The integumentary skeleton of tetrapods: origin, evolution, and development Matthew K. Vickaryous1 and Jean-Yves Sire2 1Department of Biomedical Sciences, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Canada 2Université Pierre et Marie Curie-Paris 6, UMR 7138-Systématique, Adaptation, Evolution, Paris, France Abstract Although often overlooked, the integument of many tetrapods is reinforced by a morphologically and structurally diverse assemblage of skeletal elements. These elements are widely understood to be derivatives of the once all-encompassing dermal skeleton of stem-gnathostomes but most details of their evolution and development remain confused and uncertain. Herein we re-evaluate the tetrapod integumentary skeleton by integrating comparative developmental and tissue structure data. Three types of tetrapod integumentary elements are recognized: (1) osteoderms, common to representatives of most major taxonomic lineages; (2) dermal scales, unique to gymnophionans; and (3) the lamina calcarea, an enigmatic tissue found only in some anurans. As presently understood, all are derivatives of the ancestral cosmoid scale and all originate from scleroblastic neural crest cells. Osteoderms are plesiomorphic for tetrapods but demonstrate considerable lineage-specific variability in size, shape, and tissue structure and composition. While metaplastic ossification often plays a role in osteoderm development, it is not the exclusive mode of skeletogenesis. All osteoderms share a common origin within the dermis (at or adjacent to the stratum superficiale) and are composed primarily (but not exclusively) of osseous tissue. These data support the notion that all osteoderms are derivatives of a neural crest-derived osteogenic cell population (with possible matrix contributions from the overlying epidermis) and share a deep homology associated with the skeletogenic competence of the dermis. -

Sustainable Trade in Turtles and Tortoises

Action Plan for North America Sustainable Trade in Turtles and Tortoises Commission for Environmental Cooperation Please cite as: CEC. 2017. Sustainable Trade in Turtles and Tortoises: Action Plan for North America. Montreal, Canada: Commission for Environmental Cooperation. 60 pp. This report was prepared by Peter Paul van Dijk and Ernest W.T. Cooper, of E. Cooper Environmental Consulting, for the Secretariat of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC). The information contained herein is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the governments of Canada, Mexico or the United States of America. Reproduction of this document in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes may be made without special permission from the CEC Secretariat, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. The CEC would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication or material that uses this document as a source. Except where otherwise noted, this work is protected under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial–No Derivative Works License. © Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 2017 Publication Details Publication type: Project Publication Publication date: May 2017 Original language: English Review and quality assurance procedures: Final Party review: April 2017 QA313 Project: 2015-2016/Strengthening conservation and sustainable production of selected CITES Appendix II species in North America ISBN: 978-2-89700-208-4 (e-version); 978-2-89700-209-1 (print) Disponible en français -

A Reassessment of the Taxonomic Position of Mesosaurs, and a Surprising Phylogeny of Early Amniotes

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 02 November 2017 doi: 10.3389/feart.2017.00088 A Reassessment of the Taxonomic Position of Mesosaurs, and a Surprising Phylogeny of Early Amniotes Michel Laurin 1* and Graciela H. Piñeiro 2 1 CR2P (UMR 7207) Centre de Recherche sur la Paléobiodiversité et les Paléoenvironnements (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique/MNHN/UPMC, Sorbonne Universités), Paris, France, 2 Departamento de Paleontología, Facultad de Ciencias, University of the Republic, Montevideo, Uruguay We reassess the phylogenetic position of mesosaurs by using a data matrix that is updated and slightly expanded from a matrix that the first author published in 1995 with his former thesis advisor. The revised matrix, which incorporates anatomical information published in the last 20 years and observations on several mesosaur specimens (mostly from Uruguay) includes 17 terminal taxa and 129 characters (four more taxa and five more characters than the original matrix from 1995). The new matrix also differs by incorporating more ordered characters (all morphoclines were ordered). Parsimony Edited by: analyses in PAUP 4 using the branch and bound algorithm show that the new matrix Holly Woodward, Oklahoma State University, supports a position of mesosaurs at the very base of Sauropsida, as suggested by the United States first author in 1995. The exclusion of mesosaurs from a less inclusive clade of sauropsids Reviewed by: is supported by a Bremer (Decay) index of 4 and a bootstrap frequency of 66%, both of Michael S. Lee, which suggest that this result is moderately robust. The most parsimonious trees include South Australian Museum, Australia Juliana Sterli, some unexpected results, such as placing the anapsid reptile Paleothyris near the base of Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones diapsids, and all of parareptiles as the sister-group of younginiforms (the most crownward Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Argentina diapsids included in the analyses).