Curr 8-14 the Eternal Light

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TALMUDIC STUDIES Ephraim Kanarfogel

chapter 22 TALMUDIC STUDIES ephraim kanarfogel TRANSITIONS FROM THE EAST, AND THE NASCENT CENTERS IN NORTH AFRICA, SPAIN, AND ITALY The history and development of the study of the Oral Law following the completion of the Babylonian Talmud remain shrouded in mystery. Although significant Geonim from Babylonia and Palestine during the eighth and ninth centuries have been identified, the extent to which their writings reached Europe, and the channels through which they passed, remain somewhat unclear. A fragile consensus suggests that, at least initi- ally, rabbinic teachings and rulings from Eretz Israel traveled most directly to centers in Italy and later to Germany (Ashkenaz), while those of Babylonia emerged predominantly in the western Sephardic milieu of Spain and North Africa.1 To be sure, leading Sephardic talmudists prior to, and even during, the eleventh century were not yet to be found primarily within Europe. Hai ben Sherira Gaon (d. 1038), who penned an array of talmudic commen- taries in addition to his protean output of responsa and halakhic mono- graphs, was the last of the Geonim who flourished in Baghdad.2 The family 1 See Avraham Grossman, “Zik˙atah shel Yahadut Ashkenaz ‘el Erets Yisra’el,” Shalem 3 (1981), 57–92; Grossman, “When Did the Hegemony of Eretz Yisra’el Cease in Italy?” in E. Fleischer, M. A. Friedman, and Joel Kraemer, eds., Mas’at Mosheh: Studies in Jewish and Moslem Culture Presented to Moshe Gil [Hebrew] (Jerusalem, 1998), 143–57; Israel Ta- Shma’s review essays in K˙ ryat Sefer 56 (1981), 344–52, and Zion 61 (1996), 231–7; Ta-Shma, Kneset Mehkarim, vol. -

J Ewish Community and Civic Commune In

Jewish community and civic commune in the high Middle Ages'' CHRISTOPH CLUSE 1. The following observations do not aim to provide a comprehensive phe nomenology of the J ewish community during the high and late medieval periods. Rather 1 wish to present the outlines of a model which describes the status of the Jewish community within the medieval town or city, and to ask how the concepts of >inclusion< and >exclusion< can serve to de scribe that status. Using a number of selected examples, almost exclusively drawn from the western regions of the medieval German empire, 1 will concentrate, first, on a comparison betweenJewish communities and other corporate bodies (>universitates<) during the high medieval period, and, secondly, on the means by which Jews and Jewish communities were included in the urban civic corporations of the later Middle Ages. To begin with, 1 should point out that the study of the medieval Jewish community and its various historical settings cannot draw on an overly rich tradition in German historical research. 1 The >general <historiography of towns and cities that originated in the nineteenth century accorded only sporadic attention to the J ews. Still, as early as 1866 the legal historian Otto Stobbe had paid attention to the relationship between the Jewish ::- The present article first appeared in a slightly longer German version entitled Die mittelalterliche jüdische Gemeinde als »Sondergemeinde« - eine Skizze. In: J OHANEK, Peter (ed. ): Sondergemeinden und Sonderbezirke in der Stadt der Vormoderne (Städteforschung, ser. A, vol. 52). Köln [et al.] 2005, pp. 29-51. Translations from the German research literature cited are my own. -

The Legal Status of Abuse

HM 424.1995 FAMILY VIOLENCE Rabbi Elliot N. Dorff Part 1: The Legal Status of Abuse This paper was approved by the CJT,S on September 13, 1995, by a vote of' sixteen in favor and one oppossed (16-1-0). V,,ting infiwor: Rabbis Kassel Abelson, Ben :Lion BerBm<m, Stephanie Dickstein, £/liot JY. Dorff, S/wshana Gelfand, Myron S. Geller, Arnold i'H. Goodman, Susan Crossman, Judah f(ogen, ~bnon H. Kurtz, Aaron L. iHaclder, Hwl 11/othin, 1'H(~yer HabinoLviiz, Joel /t.,'. Rembaum, Gerald Slwlnih, and E/ie Kaplan Spitz. hJting against: H.abbi Ceraicl Ze/izer. 1he Committee 011 .lnuish L(Lw and Standards qf the Rabhinical As:wmbly provides f};ztidance in matters (!f halakhnh for the Conservative movement. The individual rabbi, hou;evet~ is the authority for the interpretation and application of all maltrrs of halaklwh. 1. Reating: According to Jewish law as interpreted by the Conservative movement, under what circumstance, if any, may: A) husbands beat their wives, or wives their husbands? B) parents beat their children? c) adult children of either gender beat their elderly parents? 2. Sexual abu.se: What constitutes prohibited sexual abuse of a family member? 3· verbal abuse: What constitutes prohibited verbal abuse of a family member? TI1e Importance of the Conservative Legal Method to These Issues 1 In some ways, it would seem absolutely obvious that Judaism would nut allow individu als to beat others, especially a family member. After all, right up front, in its opening l T \VOuld like to express my sincere thanks to the members or the Committee on Jew·isll Law and Standards for their hdpfu I snggc:-;tions for impruving an earlier draft of this rcsponsum. -

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D. Stuhlman BHL, BA, MS LS, MHL In support of the Doctor of Hebrew Literature degree Jewish University of America Skokie, IL 2004 Page 1 Abstract Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs By Daniel D. Stuhlman, BA, BHL, MS LS, MHL Because of the differences in alphabets, entering Hebrew names and words in English works has always been a challenge. The Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) is the source for many names both in American, Jewish and European society. This work examines given names, starting with theophoric names in the Bible, then continues with other names from the Bible and contemporary sources. The list of theophoric names is comprehensive. The other names are chosen from library catalogs and the personal records of the author. Hebrew names present challenges because of the variety of pronunciations. The same name is transliterated differently for a writer in Yiddish and Hebrew, but Yiddish names are not covered in this document. Family names are included only as they relate to the study of given names. One chapter deals with why Jacob and Joseph start with “J.” Transliteration tables from many sources are included for comparison purposes. Because parents may give any name they desire, there can be no absolute rules for using Hebrew names in English (or Latin character) library catalogs. When the cataloger can not find the Latin letter version of a name that the author prefers, the cataloger uses the rules for systematic Romanization. Through the use of rules and the understanding of the history of orthography, a library research can find the materials needed. -

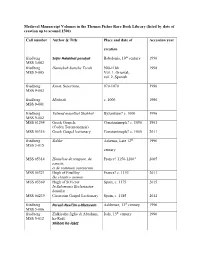

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (Listed by Date of Creation up to Around 1500) Call Number Au

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (listed by date of creation up to around 1500) Call number Author & Title Place and date of Accession year creation friedberg Sefer Halakhot pesuḳot Babylonia, 10 th century 1996 MSS 3-002 friedberg Ḥamishah ḥumshe Torah 900-1188 1998 MSS 9-005 Vol. 1, Oriental; vol. 2, Spanish. friedberg Kinot . Selections. 970-1070 1996 MSS 9-003 friedberg Mishnah c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-001 friedberg Talmud masekhet Shabbat Byzantium? c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-002 MSS 01244 Greek Gospels Constantinople? c. 1050 1901 (Codex Torontonensis) MSS 05316 Greek Gospel lectionary Constantinople? c. 1050 2011 friedberg Siddur Askenaz, Late 12 th 1996 MSS 3-015 century MSS 05314 Homeliae de tempore, de France? 1150-1200? 2005 sanctis, et de communi sanctorum MSS 05321 Hugh of Fouilloy. France? c. 1153 2011 De claustro animae MSS 03369 Hugh of StVictor Spain, c. 1175 2015 In Salomonis Ecclesiasten homiliæ MSS 04239 Cistercian Gospel Lectionary Spain, c. 1185 2012 friedberg Perush Neviʼim u-Khetuvim Ashkenaz, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-006 friedberg Zidkiyahu figlio di Abraham, Italy, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-012 ha-Rofè. Shibole ha-leḳeṭ friedberg David Kimhi. Spain or N. Africa, 13th 1996 MSS 5-010 Sefer ha-Shorashim century friedberg Ketuvim Spain, 13th century 1996 MSS 5-004 friedberg Beʼur ḳadmon le-Sefer ha- 13th century 1996 MSS 3-017 Riḳmah MSS 04404 William de Wycumbe. Llantony Secunda?, c. 1966 Vita venerabilis Roberti Herefordensis 1200 MSS 04008 Liber quatuor evangelistarum Avignon? c. 1220 1901 MSS 04240 Biblia Latina England, c. -

Medieval English Rabbis: Image and Self-Image Pinchas Roth

Medieval English Rabbis: Image and Self-Image Pinchas Roth Early Middle English, Volume 1, Number 1, 2019, pp. 17-33 (Article) Published by Arc Humanities Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/731651 [ Access provided at 2 Oct 2021 13:24 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] MEDIEVAL ENGLISH RABBIS: IMAGE AND SELF-IMAGE PINCHAS ROTH “The neglect of the British situation is explicable largely on the grounds that, compared with other northern, Ashkenazic communities, the Anglo-Jewish community was not perceived to have produced the scholarly superstars so evident in France and Germany.”1 tantalizing about the Jews of medieval England. So much about them is unknown, perhaps unknowable, and even those facts that are well known There is someThing and ostensibly unquestionable have drawn attempts2 There to were bend, no crack, Jewish or communitiesotherwise move in Anglo-Saxonthem. The chronologically England.3 first fact known about this Jewish community is that itHistory came intoof the being Jews onlyin England after the Norman Conquest. 4 The end of the But, medieval as Cecil Anglo-Jewish Roth commented experience on the is first also pageclear—the of his Edict of Expulsion of 1290 did, not“Fantasy allow hasfor any… attempted continued to Jewish carry presencethe story inback England. to a remote5 That hasantiquity.” not stopped various people from believing that Jews continued to live in England for * Boyarin and Shamma Boyarin for their kind invitation and extraordinary hospitality at the University I am deeply of Victoria. grateful to Menachem Butler for his unflagging help, and to Adrienne Williams 1 Patricia Skinner, “Introduction: Jews in Medieval Britain and Europe,” in The Jews in Medieval Britain: Historical, Literary, and Archaeological Perspectives, ed. -

The Contribution of Spanish Jewryto the World of Jewishlaw*

THE CONTRIBUTION OF SPANISH JEWRYTO THE WORLD OF JEWISHLAW* Menachem Elon Spanish Jewry's contribution to post-Talmudie halakhic literature may be explored in part in The Digest of the Responsa Literature of Spain and North Africa, a seven-volume compilation containing references to more ? than 10,000 Responsa answers to questions posed to the authorities of the day. Another source of law stemming from Spanish Jewrymay befound in the community legislation (Takanot HaKahal) enacted in all areas of civil, public-administrative, and criminal law. Among themajor questions con sider edhere are whether a majority decision binds a dissenting minority, the nature of a majority, and the appropriate procedures for governance. These earlier principles of Jewish public law have since found expression in decisions of the Supreme Court of the State of Israel. *This essay is based on the author's presentation to the Biennial Meeting of the Board of Trustees of the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture, Madrid, June 27, 1992. JewishPolitical Studies Review 5:3-4 (Fall 1993) 35 This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.82.205 on Tue, 27 Nov 2012 04:27:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 36 Menachem Elon The Contribution of Spanish Jewry to theWorld of Jewish Law The full significance of Spanish Jewry's powerful contribu tion to post-Talmudic halakhic literature demands a penetrating study. To appreciate the importance of Spanish Jewry's contri bution to the halakhic world, one need only mention, in chrono logical order, various halakhic authorities, most who lived in Spain throughout their lives, some who emigrated to, and some who immigrated from, Spain. -

The Formation of the Talmud

Ari Bergmann The Formation of the Talmud Scholarship and Politics in Yitzhak Isaac Halevy’s Dorot Harishonim ISBN 978-3-11-070945-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-070983-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-070996-4 ISSN 2199-6962 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110709834 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020950085 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Ari Bergmann, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. The book is published open access at www.degruyter.com. Cover image: Portrait of Isaac HaLevy, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Isaac_halevi_portrait. png, „Isaac halevi portrait“, edited, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ legalcode. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Chapter 1 Y.I. Halevy: The Traditionalist in a Time of Change 1.1 Introduction Yitzhak Isaac Halevy’s life exemplifies the multifaceted experiences and challenges of eastern and central European Orthodoxy and traditionalism in the nineteenth century.1 Born into a prominent traditional rabbinic family, Halevy took up the family’s mantle to become a noted rabbinic scholar and author early in life. -

THE BA'alei TOSAFOS of GERMANY 12Th

THE BA’ALEI TOSAFOS OF GERMANY 12th - 13th CENTURIES The history of Jewry in Germany is closely bound with that of France. The cultural ties between the French and German Jewish communities existed for centuries. Travel seems not to have been hampered between the academies of the two countries, even during the Crusades. The development of the French Tosafists academies, with their unique approach to Talmudic studies, was paralleled in Germany, although the work of the German scholars has come down to us in a different form from that of the French school. Where the thoughts of the French scholars exist for us largely in the collection of Tosafos, the German scholars’ words have come down to us in a more individualized form - in halachic works of individual authors. These works differ from the French Tosafists not only in individualization, but in content and purpose as well. The goal of Tosafos is the elucidation of the Talmudic texts per se, without attempting to apply the implications of their studies to practical halacha. However, the main thrust of the works of the German school is halachic application. To the German scholars, the Tosafist method was a vehicle to arrive at halachic conclusions relating to practical questions of law. The father of the German Tosafists was R. Yitzchak ben Asher I (d.1133), known as the Riva. The Riva studied in Mainz, and later became a pupil of Rashi. After spending a few years as a merchant, which sometimes involved business trips that took him as far as Russia, he repaired to Speyer where he gathered many disciples who later became the leaders of German Jewry. -

Download File

Halevy, Halivni and The Oral Formation of the Babylonian Talmud Ari Bergmann Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ari Bergmann All rights reserved ABSTRACT Halevy, Halivni and The Oral Formation of the Babylonian Talmud Ari Bergmann This dissertation is dedicated to a detailed analysis and comparison of the theories on the process of the formation of the Babylonian Talmud by Yitzhak Isaac Halevy and David Weiss Halivni. These two scholars exhibited a similar mastery of the talmudic corpus and were able to combine the roles of historian and literary critic to provide a full construct of the formation of the Bavli with supporting internal evidence to support their claims. However, their historical construct and findings are diametrically opposed. Yitzhak Isaac Halevy presented a comprehensive theory of the process of the formation of the Talmud in his magnum opus Dorot Harishonim. The scope of his work was unprecedented and his construct on the formation of the Talmud encompassed the entire process of the formation of the Bavli, from the Amoraim in the 4th century to the end of the saboraic era (which he argued closed in the end of the 6th century). Halevy was the ultimate guardian of tradition and argued that the process of the formation of the Bavli took place entirely within the amoraic academy by a highly structured and coordinated process and was sealed by an international rabbinical assembly. While Halevy was primarily a historian, David Weiss Halivni is primarily a talmudist and commentator on the Talmud itself. -

Conversion to Judaism As Reflected in the Rabbinic Writings and Culture of Medieval Ashkenaz Between Germany and Northern France

Chapter 3 Conversion to Judaism as Reflected in the Rabbinic Writings and Culture of Medieval Ashkenaz Between Germany and Northern France ePhraiM k anarfogel Attitudes Toward Converts More than a half century ago, Jacob Katz briefly sketched the attitudes that the Tosafists of northern France and Germany— and other related rabbinic decisors— displayed toward converts to Judaism. In doing so, he identified several key Talmudic interpretations and halakhic constructs as the axes around which the rabbinic positions could be charted.1 At the same time, Ben Zion Wacholder published a study on conversion to Judaism in Tosafist lit er a ture.2 Rami Reiner has supplemented these earlier efforts by focusing on the status of converts in the rabbinic thought of medieval Ashkenaz.3 Crucial to any such undertaking is the ability to distinguish between the attitude of a par tic u lar rabbinic authority to an individual convert (ger), and his sense of how accepting the Jewish community should be of the hal- akhic institution of conversion (giyyur) as a whole. As an extreme example of this problematic, one cannot properly assess Maimonides’ overall approach to conversion solely on the basis of the fact that he was obviously quite im- pressed and encouraged by the commitment and knowledge of R. ‘Ovadyah ha- Ger.4 In medieval Ashkenaz as well, leading Tosafists and halakhic Conversion to Judaism in Medieval Ashkenaz 59 authorities had interactions with individual converts. These relationships, however, do not automatically signal that these authorities favored the steady ac cep tance of converts as a matter of communal halakhic policy. -

Public Roles of Jewish Women in 14Th and 15Th-Century Ashkenaz: Business, Community and Ritual

Public Roles of Jewish Women in 14th and 15th-Century Ashkenaz: Business, Community and Ritual MARTHA KEIL (ST. PÖLTEN) It was only relatively late, not until around the mid-1980s, that the methodological 5 approaches developed in women’s and gender studies reached the area of medieval Jewish history. Since that time, a series of publications on the subject has appeared, culminating in the book on Jewish women in the High Middle Ages by Avraham Grossman, which may already be described as a standard account (even though, written in Hebrew, it has been accessible to only a limited number of readers). Most 10 of these contributions are to be ascribed to women’s studies rather than to gender studies, but ‘gender’ as a socio-cultural construct—next to categories such as religion, social status, family status, education, etc.—is receiving more and more attention. The present essay can be no more than a strictly circumscribed contribution 15 towards reconstructing the lives and worlds of Jewish women in the later medieval period. It has to leave aside the wide aspects of family life, and the roles of Jewish women as wives, mothers, and educators. The personal piety of women and their considerable halakhic expertise in questions of kashrut and niddah (ritual purity) cannot be dealt with in detail. Rather, I shall focus on the roles of women in 20 economic life, in community administration, and, on the other hand, in the socio- religious life of the community, since the thirteenth century. Over the period from the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries, the legal and social (not, however, the socio-religious) position of women in Ashkenaz, in France, and in Italy improved significantly in terms both of Jewry-law and of Jewish religious law.