Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 10/01/2021 01:57:02PM Via Free Access Independent Ladies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FANY at the Western Front an Overview of the Role of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry Corps in WW1: 1914 – 1919

1 FANY at the Western Front An overview of the role of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry Corps in WW1: 1914 – 1919 During my period of service with Lord Kitchener in the Soudan Campaign, where I had the misfortune to be wounded, it occurred to me that there was a missing link somewhere in the Ambulance Department which, in spite of the changes in warfare, had not altered very materially since the days of Crimea when Florence Nightingale and her courageous band of helpers went out to succour and save the wounded. On my return from active service I thought out a plan which I anticipated would meet the want, but it was not until September 1907 that I was able to found a troop of young women to see how my ideas on the subject would work. My idea was that each member of this Corps would receive, in addition to a thorough training in First Aid, a drilling in cavalry movements, signalling and camp work, so that nurses could ride onto the battlefield to attend to the wounded who might otherwise have been left to a slow death. Captain Edward Baker 1910 “F-A-N-Y” spelled a passing Tommy as he leant from the train. “I wonder what that stands for?” “First anywhere?” suggested another. 2 The small group of spirited women that Edward Baker gathered together in 1907, (which included his daughter, Katy), was to evolve into one of the most decorated of women’s units ever. He named them the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry Corps. -

Medical Women at War, 1914-1918

Medical History, 1994, 38: 160-177. MEDICAL WOMEN AT WAR, 1914-1918 by LEAH LENEMAN * Women had a long and difficult struggle before they were allowed to obtain a medical education.' Even in 1914 the Royal Free was the only London teaching hospital to admit them and some universities (including Oxford and Cambridge) still held out against them. The cost of a medical education continued to be a major obstacle, but at least there were enough schools by then to ensure that British women who wanted and could afford one could get it. The difficulty was in finding residency posts after qualifying, in order to make a career in hospital medicine. Few posts were available outside the handful of all-women hospitals, and medical women were channelled away from the more prestigious specialities-notably general surgery-into those less highly regarded, like gynaecology and obstetrics, and into asylums, dispensaries, public health, and, of course, general practice.2 When war broke out in August 1914, the Association of Registered Medical Women expected that women doctors would be needed mostly for civilian work, realizing that "as a result of the departure of so many medical men to the front there will be vacancies at home which medical women may usefully fill".3 As early as February 1915 it was estimated that a sixth of all the medical men in Scotland had taken commissions in the RAMC. In April of that year it was reported that "there is hardly a resident post not open to a qualified woman if she cares to apply for it". -

Full Book PDF Download

Blank page Nurse Writers of the Great War This series provides an outlet for the publication of rigorous aca- demic texts in the two closely related disciplines of Nursing History and Nursing Humanities, drawing upon both the intellectual rigour of the humanities and the practice-based, real-world emphasis of clinical and professional nursing. At the intersection of Medical History, Women’s History, and Social History, Nursing History remains a thriving and dynamic area of study with its own claims to disciplinary dis- tinction. The broader discipline of Medical Humanities is of rapidly growing significance within academia globally, and this series aims to encourage strong scholarship in the burgeoning area of Nursing Humanities more generally. Such developments are timely, as the nursing profession expands and generates a stronger disciplinary axis. The MUP Nursing History and Humanities series provides a forum within which practitioners and humanists may offer new findings and insights. The international scope of the series is broad, embrac ing all historical periods and including both detailed empirical studies and wider perspectives on the cultures of nursing. Previous titles in this series: Mental health nursing: The working lives of paid carers in the nine- teenth and twentieth centuries Edited by Anne Borsay and Pamela Dale One hundred years of wartime nursing practices, 1854–1954 Edited by Jane Brooks and Christine E. Hallett ‘Curing queers’: Mental nurses and their patients, 1935–74 Tommy Dickinson Histories of nursing practice Edited by Gerard M. Fealy, Christine E. Hallett, and Susanne Malchau Dietz Who cared for the carers? A history of the occupational health of nurses, 1880–1948 Debbie Palmer Colonial caring: A history of colonial and post-colonial nursing Edited by Helen Sweet and Sue Hawkins NURSE WRITERS OF THE GREAT WAR CHRISTINE E. -

TRAILBLAZERS: World War One’S Inspirational Women TRAILBLAZERS: World War One’S Inspirational Women Introduction

TRAILBLAZERS: World War One’s Inspirational Women TRAILBLAZERS: World War One’s Inspirational Women Introduction A trailblazer is someone who goes ahead to find a way through Key categories unexplored territory leaving markers behind which others can follow. They are innovators, the first to do something. During Arts & Culture the First World War many women were trailblazers. Even today their inspirational stories can show us the way. Activism The First World War was a time of political and social change for women. Before the war began, women were already Science protesting for the right to vote in political elections, this is known as the women’s suffrage movement. There were two main forms of women’s suffrage in the UK: the suffragists and Industry the suffragettes. Military In 1897 seperate women’s suffrage societies joined together to form the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies Definitions (NUWSS) which was led by Millicent Fawcett. Suffragists believed that women could prove they should have the right Suffrage: to vote by being responsible citizens. The right to vote in political elections The suffragettes broke away from the suffragist movement and Munition: formed the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) under Military weapons, bullets, Emmeline Pankhurst. They believed it was necessary to use and equipment illegal means to force a change in the law. Prejudice: When the war started, campaigners for women’s rights set Dislike or hostility aside their protests and supported the war effort. Millions without good reason of men left Britain to fight overseas. Women took on more Activism: public responsibilities. -

A WAR of INDIVIDUALS Bloomsbury a FINDIVIDUALS of WAR a Losuyattdst H Ra War Great the to Attitudes Bloomsbury Attitudes to the Great War

ATKIN.COV 18/11/04 3:05 pm Page 1 A WAR OF INDIVIDUALS Bloomsbury A WAR OF INDIVIDUALS Bloomsbury attitudes to the Great War attitudes to the Great War Atkin Jonathan Atkin A WAR OF INDIVIDUALS prelims.p65 1 03/07/02, 12:20 prelims.p65 2 03/07/02, 12:20 A WAR OF INDIVIDUALS Bloomsbury attitudes to the Great War JONATHAN ATKIN Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave prelims.p65 3 03/07/02, 12:20 Copyright © Jonathan Atkin 2002 The right of Jonathan Atkin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6070 2 hardback ISBN 0 7190 6071 1 paperback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs. www.freelancepublishingservices.co.uk Printed in Great Britain by Bookcraft (Bath) Ltd, Midsomer Norton prelims.p65 4 03/07/02, 12:20 Contents Acknowledgements -

The Balkans Viewed by Scottish Medical Women

Revista Română de Studii Baltice şi Nordice, Vol. 4, Issue 1 (2012): pp. 53-82 ROM THE FRINGE OF THE NORTH TO THE BALKANS: THE BALKANS VIEWED FBY SCOTTISH MEDICAL WOMEN DURING WORLD WAR I Costel Coroban Head of Department for Humanities and Social Studies, Cambridge International Examinations Center Constanta; Grigore Gafencu Research Center, Valahia University of Târgovişte; E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgments This paper has been presented at the Third International Conference on Nordic and Baltic Studies: European networks: the Balkans, Scandinavia and the Baltic world in a time of economic and ideological crisis hosted by the Romanian Association for Baltic and Nordic Studies, Târgoviste, May 25-27, 2012. Gathering materials for this research would not have been possible without the help of Dr. Harry T. Dickinson (Professor Emeritus at the School of History, Classics and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh) and Dr. Jane McDermid (Senior Lecturer at the School of Humanities, University of Southampton). Also I must thank Mr. Robert Redfern-West (Director of Academica Press, LLC) and Dr. Vanessa Heggie (Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge). Not least, I must also mention the help provided by Mr. Benjamin Schemmel (editor of www.rulers.org). I am compelled to express my profound gratitude for their help. Abstract: This article is about the venture of the units of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals organization in the Balkans during World War I. It is important to note that these women, inspired by the ideals of equality and compassion, were not part of any governmental organization, as the British War Office refused to employ them, and thus acted entirely based on their ideals. -

Full Book PDF Download

ATKIN.COV 18/11/04 3:05 pm Page 1 A WAR OF INDIVIDUALS Bloomsbury A WAR OF INDIVIDUALS Bloomsbury attitudes to the Great War attitudes to the Great War Atkin Jonathan Atkin A WAR OF INDIVIDUALS prelims.p65 1 03/07/02, 12:20 prelims.p65 2 03/07/02, 12:20 A WAR OF INDIVIDUALS Bloomsbury attitudes to the Great War JONATHAN ATKIN Manchester University Press Manchester prelims.p65 3 03/07/02, 12:20 Copyright © Jonathan Atkin 2002 The right of Jonathan Atkin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA, UK www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6070 2 hardback ISBN 0 7190 6071 1 paperback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs. www.freelancepublishingservices.co.uk prelims.p65 4 03/07/02, 12:20 Contents Acknowledgements and abbreviations—page vi Introduction—1 1 ‘Recognised’ forms of opposition 10 2 Bloomsbury 17 3 Academics at war – Bertrand Russell and Cambridge 52 4 Writers at war 77 5 Writers in uniform 102 6 Women and the war 131 7 Obscurer individuals and their themes of response 163 8 Three individuals 193 9 Public commentary on familiar themes 209 Conclusion—224 Bibliography—233 Index—245 prelims.p65 5 03/07/02, 12:20 Acknowledgements and abbreviations I would like to thank my tutors at the University of Leeds, Dr Hugh Cecil and Dr Richard Whiting, for their continued advice, support and generosity when completing my initial PhD. -

1 a Bibliography: the Great War (1914-1918)

A BIBLIOGRAPHY: THE GREAT WAR (1914-1918) (Bibliography under construction)1 Authors: Jason F. Kovacs and Brian S. Osborne2 17 April 2014 1 N.B.: This foray into the extensive literature on the Great War is intended as an introductory aid for researchers and interested readers. The principal collators of this collection, and the WHTRN, are both aware of the dominance of English language references below, and also that some infelicities in style and in editing remain. We welcome additional contributions and corrections to this ongoing project. 2 Other contributors: Alan Brunger; Richard Butler; Mallika Das; Wanda George; Anne Hertzog; Roy Jones; Sandra Peterman; John Stephens; Jamie Swift; Myriam Jansen-Verbeke; Caroline Winter. Reference to use when citing bibliography: Kovacs, Jason F. and Brian S. Osborne (2014). A Bibliography: The Great War (1914-1918). Halifax, NS: World Heritage Tourism Research Network, Mount Saint Vincent University. 1 CATEGORIES: ORIGINS AND CONSEQUENCES ................................................................................................................................................. 4 WAR AIMS, ALLIANCES, AND DIPLOMACY ......................................................................................................................... 22 TREATIES AND LEGACIES ...................................................................................................................................................... 26 NATIONAL PARTICIPATIONS IN THE GREAT WAR ............................................................................... -

1935: the Case of the Honourable Fraternity of Antient Masonry

1 Women Freemasons and Feminist causes 1908 - 1935: The Case of the Honourable Fraternity of Antient Masonry Ann Jessica Pilcher-Dayton, B.A. Thesis submitted to the Department of History, University of Sheffield for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2011 2 Abstract An important but hitherto unstudied aspect of the women's movement in Britain between 1900 and 1935 was the appearance of organisations of Freemasons which admitted women. This thesis is a case study of one such body, the Honourable Fraternity of Antient Masonry (HFAM). The roots of women's Freemasonry reach back to the eighteenth-century French Lodges of Adoption. In 1902, the social reformer and Theosophist Annie Besant established a lodge of the French-based International Order of Co-Freemasonry, Le Droit Humain, in London. In 1908, the clergyman William Cobb led a secession from Besant's Order and created the HFAM, which under the charismatic leadership of Cobb and his successor Marion Halsey, became the largest British Masonic Order admitting women. An analysis of HFAM's social composition shows the dominance of aristocratic women during the period before 1914 and illustrates the functioning of social networks in support of the women's movement. HFAM mobilised these networks to support the campaign for women's suffrage. An innovative social experiment by the HFAM was the establishment in 1916 of the Halsey Training College to train secondary school teachers. With the expansion of the social basis of HFAM's membership after the First World War, HFAM's organisation of its philanthropic activities changed with the establishment of its Bureau of Service. -

'Taking the Long Journey' January 2016

‘Taking the Long Journey’ Australian women who served with allied countries and paramilitary organisations during World War One Selena Estelle Williams January 2016 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University This thesis contains no material which has previously been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made. SIGNED DATE: ii Philip Maurice Turnedge 20 June 1935 - 7 March 2015 iii CONTENTS CONTENTS iv LIST OF TABLES vi LIST OF IMAGES vii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xi ABSTRACT xiii INTRODUCTION 1 RESTRICTIONS ON WOMEN’S SERVICE AND EMPLOYMENT 4 THE ANZAC LEGEND AND NATIONAL IDENTITY 7 HISTORIOGRAPHY 10 THE RETURN HOME 18 DETERMINING THE NUMBERS 19 FICTION, NON-FICTION, TELEVISION AND INTERNET 22 METHODOLOGY 25 CHAPTER ONE 31 THE ORGANISATIONS AND SERVICES OF WAR 31 VOLUNTARY AID DETACHMENTS 37 FEMALE DOCTORS 46 NURSES AND NURSING SERVICES 53 MASSAGE AND MASSEURS 70 PARAMILITARY UNITS AND WOMEN’S SERVICES 72 ENQUIRY UNITS FOR PRISONERS OF WAR AND MISSING PERSONNEL 76 CONCLUSION 83 CHAPTER TWO 85 TRAVELLING THE ROAD TO WAR 85 THE NOTION OF THE ‘AUSTRALIAN GIRL’ 89 MUSIC AND THEATRE: WOMEN ENTERTAINERS – A BOOST TO MORALE 103 ARTISTS IN WAR 112 WRITERS IN WAR 122 GENDER, WAR AND NATIONAL IDENTITY 127 CONCLUSION 130 CHAPTER THREE 132 THE MEDICAL SERVICES IN WAR - DIVERSE LOCATIONS, ENVIRONMENTS -

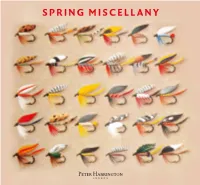

Spring Miscellany

SPRING MISCELLANY All items arePeter fully described Harrington and photographed at peterharrington.co.uk n1 london Subject index Welcome to our spring 2020 miscellany Aviation We’ve had a busy few weeks at Peter Harrington, keeping 29, 32, 53, 105, 116, 117, 194 up with the rapid changes to which business and life have had to adapt. Bindings 6, 21, 37, 73, 78, 108 I’m happy to say that all of our company members are well and Children’s books have been working hard remotely to ensure that we remain 13, 37, 52, 61, 106, 107, 110–12, able to offer books to our customers. 129, 149, 151, 157, 165, 166 Given the circumstances, we’ve made some changes: Computing 182, 192, 193 • We have temporarily closed our physical shops in Mayfair and Chelsea, in line with British government Economics advice, but our website is fully operational at 11, 28, 68, 69, 74, 100, 103, www.peterharrington.co.uk and you can continue 104, 121, 127, 169 to browse and purchase items online. Literature 2, 8, 9, 25, 33, 36, 51, 58, 59, • We can easily set up appointments via 60, 65–7, 78, 83–6, 93, 94, Skype, Zoom, or your preferred platform to 97, 101, 102, 108, 113, 120, 122, view and discuss any item in greater detail. 123, 126, 132, 136, 139, 154, Our specialists are all available at short notice. 158, 160, 167, 170–3, 179–81, • UPS and Royal Mail shipping operate as normal 183, 184, 187, 198, 199 and we continue to fulfil all orders. -

Clinics and Home Visits in Hampstead

www.hgs.org.uk Issue 119 · Summer 2014 Susie’s Proms Looking Samantha magic works to join takes to wonders again, a choir? the streets, page 5 See page 11 page 12 Election for Trust council WHITE DAVID The next AGM of the Hampstead and developers think that the So if you are a member, Garden Suburb Trust will be Trust lacks the will or resources please use your vote for a upon us in September and this to do so, they will be quick to candidate who, by supporting year it will be followed by the exploit the weakness. It is up to the objectives of the Trust, will election of one new member to us to show by our votes that we put the Suburb first. the Trust Council. As we go to are prepared to support those who Finally it is very important press Saul Zadka, who stands will protect us. Trustees should for me to say that the above down by rotation, has indicated also encourage the continuation represents my personal views that he will not stand for a and development of the new and not those of anyone else or further three years. policy of communication and any group. A trustee has to ensure a consultation with residents. TERRY BROOKS charity remains true to its charitable purpose and objects as set out in its governing One candidate to date documents. For us this means member of the Insolvency that our trustees ensure the Practitioners Association. Trust does all things possible to David is committed to the maintain and preserve the ethos and principles that the present character and amenities Suburb embodies and strongly of the Suburb using the tools at believes that it is important to its disposal.