1935: the Case of the Honourable Fraternity of Antient Masonry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2019 Published with the Authority of the Supreme Grand Royal Arch Chapter of Ireland Contents

AR L RC A H Y H Y O C R H A A D P P N N T T A A E E R R R R G G Supreme Grand Royal Arch Chapter of Ireland Annual Report 2019 Published with the Authority of the Supreme Grand Royal Arch Chapter of Ireland Contents Supreme Grand Royal Arch Chapter Report 2019 3 Down 30 AR L RC A H Y H Y O C R H A A D P P N N T T A A E E R R R R G G 1 Gibraltar 50 Jamaica 51 New Zealand 52 Zambia 55 AR L RC A H Y H Y O C R H A A D P P N N T T A A E E R R R R G G 2 Supreme Grand Royal Arch Chapter of Ireland Report 2019 AR L RC A H Y H Y O C R H A A D P P N N T T A A E E R R R R G G 3 Supreme Grand Royal Arch Chapter to the AR L RC A H Y H Y O C R H A A D P P N N T T A A E E R R R R G G AR L RC A H Y H Philip A.J. -

Colonial American Freemasonry and Its Development to 1770 Arthur F

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 12-1988 Colonial American Freemasonry and its Development to 1770 Arthur F. Hebbeler III Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hebbeler, Arthur F. III, "Colonial American Freemasonry and its Development to 1770" (1988). Theses and Dissertations. 724. https://commons.und.edu/theses/724 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - ~I lII i I ii !I I I I I J: COLONIAL AMERICAN FREEMASONRY I AND ITS DEVELOPMENT TO 1770 by Arthur F. Hebbeler, III Bachelor of Arts, Butler University, 1982 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota December 1988 This Thesis submitted by Arthur F. Hebbeler, III in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts from the University of North Dakota has been read by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whom the work has been done, is hereby approved. ~~~ (Chairperson) This thesis meets the standards for appearance and conforms to the style and format requirements of the Graduate School of the University of North Dakota, and is hereby approved. -~ 11 Permission Title Colonial American Freemasonry and its Development To 1770 Department History Degree Master of Arts In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the require ments for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the Library of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. -

International 2012.Pdf

Le Droit Humain # 37 InternatIonal Special International Convention 2012 — EN ordre Maçonnique Mixte International Le Droit Humain Le Droit Humain #37 Special Issue on the International Convention held at les Salons de l’aveyron, Paris from 16 to 20 May 2012 edition: Communication Commission February 2013 INDEX Opening speech of the XIV International Convention 4 Most Illustrious Sister Danièle Juette Past Grand Master and Sovereign Grand Commander of the Order Impressions on the International Convention 10 Sister Jóhanna Sigurjónsdóttir Icelandic federation A harmonious Babel 14 Brother Luis Alberto Acebal Argentinian jurisdiction Memories and experiences 18 Brother Pedro-José Vila Spanish federation Report from Australia 22 Most Illustrious Sister Laura R. Ealey Australian federation Closing speech of the XIV International Convention 24 Most Illustrious Sister Yvette Ramon Grand Master and Sovereign Grand Commander of the Order OpenIng speeCh oF the XIV InternatIonal ConVentIon — V.·. Ill.·. s.·. DanIèle Juette Past grand Master and Sovereign grand Commander of the order My Sisters and Brothers in your various degrees and capacities, It is a deeply emotional moment to see us all gathered here, arriving as we have from our various Orients for this, the 14th International Convention of our Order. It is an exceptional moment of coming together, enabling us to experience universal brotherhood first hand. This is what our founders wished for. In creating our Order, by way of the Declaration of Principles and the first three Articles of our International Con- stitution, they expressed the desire that our meetings and exchanges should take place marked not by religious, ethnic or national identity but simply by our common humanity. -

FREEMASONRY And/ Or MASON And/ Or MASONS And/ Or SHRINERS And/ Or SHRINER and the Search Results Page

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY CENTRAL SECURITY SERVICE FORT GEORGE G. MEADE, MARYLAND 20755-6000 FOIA Case: 85473A 30 September 20 16 JOHN GREENEWALD Dear Mr. Greenewald: This responds to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request of 15 September 2016 for lntellipedia entries on FREEMASON andjor FREEMASONRY and/ or MASON and/ or MASONS and/ or SHRINERS and/ or SHRINER and the search results page. As stated in our initial response letter, dated 19 September 2016, your request was assigned Case Number 854 73. For purposes of this request and based on the information you provided in your letter, you are considered an "all other" requester. As such, you are allowed 2 hours of search and the duplication of 100 pages at no cost. There are no assessable fees for this request. A copy of your request is enclosed. Your request has been processed under the FOIA. For your information, NSA provides a service of common concem for the Intelligence Community (IC) by serving as the executive agent for lntelink. As such, NSA provides technical services that enable users to access and share information with peers and stakeholders across the IC and DoD. Intellipedia pages are living documents that may be originated by any user organization, and any user organization may contribute to or edit pages after their origination. -

Gould's History of Freemasonry

GOULD'S HISTORY OF FREEMASONRY THROUGHOUT THE WORLD VOLUME III From a photograph by Underwood and Underwood . King Gustav of Sweden . From the painting by Bernhard Osterman . .o .o.o.o.o .o .o .o .o .o .o .o .o .o.o 0 0 0 Eas 0 xxo~ m~N o En o SNOS S,2i3[~I8I2iDS S3ZU 0 ,XHJ o ~y<~~ v o +5 0 0 0 a 0 0 0 0 III 3I~1Ifl 0 ZOn o Eys, 0 0 v v v 4 o~ 0 a ////~I1\`\ •O E 7S, 0 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Ey; 0 v Gl"HOm 9H~L .Lf10HO110UH,L o E-r, v0 0 0 v 0 v IN A 0 s vw a 4 N 0 0 0 40 v E-1 0 A S vs 0 I( I H S~QZ~109 a $ u eee.e.e.e.eee .e.e.ae.a.e.e.e.e.e.e .ese.e.e.e.e.eeeeee <~ .eee0 .e.e.e.eee.e.e.e.e.oee.e .e. v Z/~~Z/~~S?/~~SZ/~~SZ/n~SZ/ti~5?/~~SZh~SZ/~15Z/~~S?h\SZ/,~5?h~S~/n~S?/\5?/~\SZ/n~S?h~S~/n~SZ/n~SZln~?!~~ W` ,~` W~ W~ W~ W` W` W` W` ~W w.! W~ W` i~W rW W` W~ W` wy y uy J1 COPYRIGHT, 1936, BY CHARLES SCRIBNER ' S SONS PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OP AMERICA ww •o •o •o ww •oww•o•ow•wo•o w•o •aoww •o•o •o•o•o•o•o •wo •o •owwwww•ow•o www•o• 0 I ° GOULD'S HISTORY OF FREEMASONRY THROUGHOUT THE WORLD REVISED BY DUDLEY WRIGHT EDITOR OF THE MASONIC NEWS THIS EDITION IN SIX VOLUMES EMBRACES NOT ONLY AN Q Q INVESTIGATION OF RECORDS OF THE ORGANIZATIONS OF THE FRATERNITY IN ENGLAND, SCOTLAND, IRELAND, THE BRITISH COLONIES, EUROPE, ASIA, AFRICA AND SOUTH AMERICA, BUT INCLUDES ADDITIONAL MATERIAL ESPE- CIALLY PREPARED ON EUROPE, ASIA, AND AFRICA, ALSO o b CONTRIBUTIONS BY DISTINGUISHED MEMBERS OF THE FRATERNITY COVERING EACH OF THE o FORTY-EIGHT STATES, DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA AND THE POSSESSIONS OF THE b o UNITED STATES 4 4 THE PROVINCES OF CANADA AND THE 4 COUNTRIES OF LATIN AMERICA b UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF 0 MELVIN M. -

2011 Commission Report

2011 Commission Report BAJA CALIFORNIA The two groups representing the Grand Lodge of Baja California have now worked out an agreement that has unified them again into one regular Grand Lodge. The leaders of the two groups have signed the agreement, and have assured it will be ratified by both groups. The Grand Lodge of Baja California has now satisfied the standards for recognition. BULGARIA There continues to be no progress in the unification of Freemasonry in Bulgaria. Since they have previously been determined to meet the standards for recognition, there is no interest on the part of the United Grand Lodge of Bulgaria in entering discussions with the Grand Lodge AF&AM of Bulgaria, either for unification or for establishing a treaty to share the jurisdiction. Both of these Grand Lodges appear to practice regular Masonry, and both were of the same origin until they split in 2001. This Commission has urged the two Grand Lodges to resolve their differences for the past seven years to no avail; therefore this issue will not be addressed again until the brethren in Bulgaria reach some type of agreement. CYPRUS The United Grand Lodge of England and the Grand Lodge of Cyprus have reached an accord whereby they will both share the jurisdiction of Cyprus, and have established fraternal relations among themselves. The Grand Lodge of Cyprus therefore now meets all the standards for recognition. CZECH REPUBLIC The Grand Lodge of the Czech Republic informed us that an irregular body calling itself the Czech National Grand Lodge was recently created by a group of dissident members who defected and formed this new organization. -

1 the ANCIENT* LANDMARKS of the ORDER *Throughout I Have

THE ANCIENT* LANDMARKS OF THE ORDER *Throughout I have used the spelling “Ancient” rather than “Antient.” W.BRO. A.D. MATTHEWS PPGReg Issue 4: - 9th April 2013 Remove not the ancient landmark, which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22: 28 What are the Landmarks? How many are there and where are they defined? I turn for guidance, first to the Book of Constitutions of the United Grand Lodge of England, which states in: Rule 4: “The Grand Lodge possesses the supreme super-intending authority and alone has the inherent power of enacting laws and regulations for the government of the Craft, and of altering, repealing and abrogating them, always taking care that the ancient Landmarks of the Order be preserved.” 1 Rule 55 “If it shall appear to the Grand Master that any proposed resolution contains anything contrary to the ancient Landmarks of the Order, he may refuse to permit the same to be discussed.” 1 Rule 111 “Every Master Elect, before being passed to the Chair, shall solemnly pledge himself to preserve the Landmarks of the Order.” 1 Rule 125(b) “No Brother who is not subject to the Grand Lodge shall be admitted unless his Certificate shows that he has been initiated according to the ancient rites and ceremonies in a Lodge belonging to a Grand Lodge professing belief in TGAOTU…… nor unless he himself shall acknowledge that this belief is an essential Landmark of the Order ……..” 1 These are the only references to the Ancient Landmarks in the Book of Constitutions and there is no defined list therein, so all we can determine so far is that a professed belief in TGAOTU is an Ancient Landmark of the Order and the only one specifically defined as such by the United Grand Lodge of England. -

Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19 to the 21 St Centuries

Centre for British Studies International Conference Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 Conference: Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 P R O G R A M M E Venue: Faculty of Political Science of the University of Belgrade, Jove Ilića 165 Friday, January 26, 2018 12.00–12.50 Opening of the Conference: H. E. Denis Keefe, CMG, HM Ambassador to Serbia Prof. Dragan Simić, Dean of the Faculty of Political Science, Belgrade Prof. em. Vukašin Pavlović, President of the Council of the Centre for British Studies, FPS, UoB 13.00–14.30 Panel 1: Serbia, the UK, and Global World Chairperson: Dr. Spyros Economides, London School of Economics and Political Science Panellists: Sir John Randall, former Member of Parliament and Government Deputy Chief Whip British-Serbian Relations H. E. Amb. Branimir Filipović, Assistant Minister, MFA of Serbia British-Serbian Relations since 2000. A View from Serbia David Gowan, CMG, former ambassador of the UK to Serbia and Montenegro British-Serbian Relations since 2000. A View from Britain Prof. Christopher Coker, London School of Economics Britain and the Balkans in Global World 14.30–15.45 Lunch break 1 Conference: Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 15.45–17.15 Panel 2: Diffi cult Legacies and New Opportunities Chairperson: Prof. Slobodan G. Markovich, Centre for British Studies, FPS, UoB Panellists: Dr. Spyros Economides, London School of Economics Legacy of UN Interventionism in British-Serbian Relations Prof. -

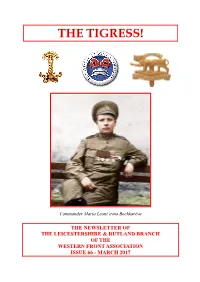

Issue 66 - March 2017 Editorial

THE TIGRESS! Commander Maria Leont’evna Bochkarëva THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LEICESTERSHIRE & RUTLAND BRANCH OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION ISSUE 66 - MARCH 2017 EDITORIAL Welcome again, Ladies and Gentlemen, to the latest edition of “The Tiger”, rechristened “The Tigress” for this special ladies edition! Despite whiling away many a youthful hour under a candlewick bedspread listening to Radio Luxembourg 208, I don’t seem to have much time these days to listen to the radio but I noticed that, on 8th March, Radio 3 dedicated its whole day’s playlist, in recognition of their bold and diverse contribution to music, to female composers one of whom being Elisabeth Lutyens, daughter of architect Edwin. Why did the BBC decide to do this? It was to celebrate International Women’s Day (IWD). I was reminded of the impending IWD last month when researching the remarkable exploits of Russian women in 1917 without whom the revolution may not have occurred exactly as it did 100 years ago. Their story will be recounted later in this Newsletter . The month of March itself could even be described as “Ladies Month” since its very flower, the daffodil, is also known as the birth flower, and its 31 days contain not only IWD (8th) but Lady Day or Annunciation Day (25th) and Mothering Sunday (26th). Militarily, of course, March was named after Mars, the Roman god of war whose month was Martius and from where originated the word martial. Another definition of March is “walk in a military manner with a regular measured tread”, a meaning which countless troops over the centuries learned as part of their basic training. -

The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P

The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett The Early Days of Theosphy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett Theosophical Publishing House Ltd, London, 1922 NOTE [Page 5] Mr. Sinnett's literary Executor in arranging for the publication this volume is prompted to add a few words of explanation. There is naturally some diffidence experienced in placing before the public a posthumous MSS of personal reminiscences dealing in various instances with people still living. It would, however, be impossible to use the editorial blue pencil without destroying the historical value of the MSS. Mr. Sinnett's position and associations with the Theosophical Society together with his standing as an author in the Theosophical movement alike demand that his last writing should be published, and it is left to each reader to form his own judgment as to the value of the book in the light of his own study of the questions involved. Page 1 The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett CHAPTER - 1 - NO record could truly be called a History of the Theosophical Society if it concerned itself merely with events taking shape on the physical plane of life. From the first such events have been the result of activities on a higher plane; of steps taken by the unseen Powers presiding over human evolution, whose existence was unknown in the outer world when their great undertaking — the Theosophical Movement — was originally set on foot. To those known in the outer world as the Founders of the Theosophical Society — Madame Blavatsky and Colonel Olcott — the existence of these higher powers, The Brothers as they were called at first, was more or less imperfectly comprehended. -

Process Paper and Bibliography

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Books Kenney, Annie. Memories of a Militant. London: Edward Arnold & Co, 1924. Autobiography of Annie Kenney. Lytton, Constance, and Jane Warton. Prisons & Prisoners. London: William Heinemann, 1914. Personal experiences of Lady Constance Lytton. Pankhurst, Christabel. Unshackled. London: Hutchinson and Co (Publishers) Ltd, 1959. Autobiography of Christabel Pankhurst. Pankhurst, Emmeline. My Own Story. London: Hearst’s International Library Co, 1914. Autobiography of Emmeline Pankhurst. Newspaper Articles "Amazing Scenes in London." Western Daily Mercury (Plymouth), March 5, 1912. Window breaking in March 1912, leading to trials of Mrs. Pankhurst and Mr. & Mrs. Pethick- Lawrence. "The Argument of the Broken Pane." Votes for Women (London), February 23, 1912. The argument of the stone: speech delivered by Mrs Pankhurst on Feb 16, 1912 honoring released prisoners who had served two or three months for window-breaking demonstration in November 1911. "Attempt to Burn Theatre Royal." The Scotsman (Edinburgh), July 19, 1912. PM Asquith's visit hailed by Irish Nationalists, protested by Suffragettes; hatchet thrown into Mr. Asquith's carriage, attempt to burn Theatre Royal. "By the Vanload." Lancashire Daily Post (Preston), February 15, 1907. "Twenty shillings or fourteen days." The women's raid on Parliament on Feb 13, 1907: Christabel Pankhurst gets fourteen days and Sylvia Pankhurst gets 3 weeks in prison. "Coal That Cooks." The Suffragette (London), July 18, 1913. Thirst strikes. Attempts to escape from "Cat and Mouse" encounters. "Churchill Gives Explanation." Dundee Courier (Dundee), July 15, 1910. Winston Churchill's position on the Conciliation Bill. "The Ejection." Morning Post (London), October 24, 1906. 1 The day after the October 23rd Parliament session during which Premier Henry Campbell- Bannerman cold-shouldered WSPU, leading to protest led by Mrs Pankhurst that led to eleven arrests, including that of Mrs Pethick-Lawrence and gave impetus to the movement. -

FREEMASONRY in SOUTHEAST EUROPE from the 19TH to the 21ST CENTURIES Edited by Slobodan G

Freemasonry in Southeast Europe from the 19th to the 21 st Centuries Editor Slobodan G. Markovich FREEMASONRY IN SOUTHEAST EUROPE FROM THE 19TH TO THE 21ST CENTURIES Edited by Slobodan G. Markovich FREEMASONRY IN SOUTHEAST EUROPE FROM THE 19TH TO THE 21ST CENTURIES Publishers Zepter Book World, Belgrade Institute for European Studies, Belgrade Executive Publisher Dosije Studio, Belgrade For the Publishers Mrs. Slavka StevanoviÏ, head of Zepter Book World Dr Misha Djurkovich, Director of the Institute for European Studies Mirko MiliÏeviÏ, Director of Dosije Studio The publication of this book has been supported by the Regular Grand Lodge of Serbia within the framework of the celebration of the centenary of the Grand Lodge “Jugoslavia/Yugoslavia”. FREEMASONRY IN SOUTHEAST EUROPE FROM THE 19th TO THE 21st CENTURIES Edited by Slobodan G. Markovich Belgrade, 2020 Pictures on the covers: Front Cover: Alphonse Mucha’s poster for his exhibition “Slovanská epopej” [“The Slavic Epic”] organised in Brno in June-September 1930. Slavic god Svantovit/Svetovid with four faces is in the background. Back cover: Medal of the Grand Lodge “Yugoslavia” from the late 1930s. From the private collection of the Homen family, Belgrade. CONTENTS Slobodan G. Markovich, Editor’s Note . 7 Freemasonry in Interwar Europe Wolfgang Schmale, The “Grande Loge de France” in the Interwar Period and its Grand Debates on Peace, Colonialism, and the “United States of Europe” . 17 Eric Beckett Weaver, Shades of Darkness. Anti-masonic Politics in Interwar Hungary, and the Shadows They Cast Today . 35 Italian and Hungarian Freemasonry and their Impact on Southeast Europe Fulvio Conti, The Grand Orient of Italy and the Balkan and Danubian Europe Freemasonries.