'Taking the Long Journey' January 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RCN History of Nursing Society Newsletter

HISTORY OF NURSING SOCIETY Spring 2016 History of Nursing Society newsletter Contents HoNS round-up P2 Cooking up a storm P4 Nurses’ recipes from the past RCN presidents P5 A history of the College’s figureheads Mary Frances Crowley P6 An Irish nursing pioneer Northampton hospital P7 The presidents’ exhibition A home for nurses at RCN headquarters Book reviews P8 A centenary special Welcome to the spring 2016 issue of the RCN History of Nursing Society Something to say? (HoNS) newsletter Send contributions for It can’t have escaped your attention that the RCN is celebrating its centenary this year and the the next newsletter to HoNS has been actively engaged in the preparations. We will continue to be involved in events the editor: and exhibitions as the celebrations progress over the next few months. Dianne Yarwood The centenary launch event took place on 12 January and RCN Chief Executive Janet Davies and President Cecilia Anim said how much they were looking forward to the events of the year ahead. A marching banner, made by members of the Townswomen’s Guilds, was presented to the College (see p2). The banner will be taken to key RCN events this year, including Congress, before going on permanent display in reception at RCN headquarters in London. The launch event also saw the unveiling of the RCN presidents’ exhibition, which features photographs of each president and short biographical extracts outlining their contributions to the College (see p5). There was much interest in the new major exhibition in the RCN Library and Heritage Centre. The Voice of Nursing explores how nursing has changed over the past 100 years by drawing on stories and experiences of members and items and artefacts from the RCN archives. -

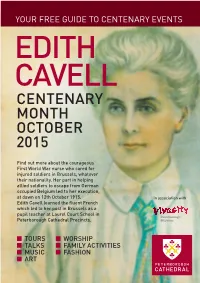

Edith Cavell Centenary Month October 2015

YOUR FREE GUIDE TO CENTENARY EVENTS EDITH CAVELL CENTENARY MONTH OCTOBER 2015 Find out more about the courageous First World War nurse who cared for injured soldiers in Brussels, whatever their nationality. Her part in helping allied soldiers to escape from German occupied Belgium led to her execution, at dawn on 12th October 1915. In association with Edith Cavell learned the fluent French which led to her post in Brussels as a pupil teacher at Laurel Court School in Peterborough Peterborough Cathedral Precincts. MusPeeumterborough Museum n TOURS n WORSHIP n TALKS n FAMILY ACTIVITIES n MUSIC n FASHION n ART SATURDAY 10TH OCTOBER FRIDAY 9TH OCTOBER & SUNDAY 11TH OCTOBER Edith Cavell Cavell, Carbolic and A talk by Diana Chloroform Souhami At Peterborough Museum, 7.30pm at Peterborough Priestgate, PE1 1LF Cathedral Tours half hourly, Diana Souhami’s 10.00am – 4.00pm (lasts around 50 minutes) biography of Edith This theatrical tour with costumed re-enactors Cavell was described vividly shows how wounded men were treated by The Sunday Times during the Great War. With the service book for as “meticulously a named soldier in hand you will be sent to “the researched and trenches” before being “wounded” and taken to sympathetic”. She the casualty clearing station, the field hospital, will re-tell the story of Edith Cavell’s life: her then back to England for an operation. In the childhood in a Norfolk rectory, her career in recovery area you will learn the fate of your nursing and her role in the Belgian resistance serviceman. You will also meet “Edith Cavell” and movement which led to her execution. -

'Women in Medicine & Scottish Women's Hospitals'

WWI: Women in Medicine KS3 / LESSONS 1-5 WORKSHEETS IN ASSOCIATION WITH LESSON 2: WORKSHEET Elsie Ingis 1864 – 1917 Elsie Inglis was born in 1864, in the small Indian town of Naini Tal, before moving back to Scotland with her parents. At the time of her birth, women were not considered equal to men; many parents hoped to have a son rather than a daughter. But Elsie was lucky – her mother and father valued her future and education as much as any boy’s. After studying in Paris and Edinburgh, she went on to study medicine and become a qualified surgeon. Whilst working at hospitals in Scotland, Elsie was shocked to discover how poor the care provided to poorer female patients was. She knew this was not right, so set up a tiny hospital in Edinburgh just for women, often not accepting payment. Disgusted by what she had seen, Elsie joined the women’s suffrage campaign in 1900, and campaigned for women’s rights all across Scotland, with some success. In August 1914, the suffrage campaign was suspended, with all efforts redirected towards war. But the prejudices of Edwardian Britain were hard to break. When Elsie offered to take an all-female medical unit to the front in 1914, the War Office told her: “My good lady, go home and sit still.” But Elsie refused to sit still. She offered help to France, Belgium and Serbia instead – and in November 1914 dispatched the first of 14 all-women medical units to Serbia, to assist the war effort. Her Scottish Women’s Hospitals went on to recruit more than 1,500 women – and 20 men – to treat thousands in France, Serbia, Corsica, Salonika, Romania, Russia and Malta. -

Edicai Uvuali

THE I + edicaI+. UVUaLI THE JOURNAL OF THE BRITISH MEDICAL ASSOCIATION. EDITED BY NORMAN GERALD HORNER, M.A., M.D. VOLUTME I, 1931. JANUARY TO JUNE. XtmEan 0n PRINTED AND PUBLISHED AT THE OFFICE OF THE BRITISH MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, TAVISTOCK SQUARE, LONDON, W.C.1. i -i r TEx BsxTzSu N.-JUNE, 19311 I MEDICAL JOUUNAI. rI KEY TO DATES AND PAGES. THE following table, giving a key to the dates of issue andI the page numbers of the BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL and SUPPLEMENT in the first volume for 1931, may prove convenient to readers in search of a reference. Serial Date of Journal Supplement No. Issue. Pages. Pages. 3652 Jan. 3rd 1- 42 1- 8 3653 10th 43- 80 9- 12 3654 it,, 17th 81- 124 13- 16 3655 24th 125- 164 17- 24 3656 31st 165- 206 25- 32 3657 Feb. 7th 207- 252 33- 44 3658 ,, 14th 253- 294 45- 52 3659 21st 295- 336 53- 60 3660 28th 337- 382 61- 68 3661 March 7th 383- 432 69- 76 3662 ,, 14th 433- 480 77- 84 3663 21st 481- 524 85- 96 3664 28th 525- 568 97 - 104 3665 April 4th 569- 610 .105- 108 3666 11th 611- 652 .109 - 116 3667 18th 653- G92 .117 - 128 3668 25th 693- 734 .129- 160 3669 May 2nd 735- 780 .161- 188 3670 9th 781- 832 3671 ,, 16th 833- 878 .189- 196 3672 ,, 23rd 879- 920 .197 - 208 3673 30th 921- 962 .209 - 216 3674 June 6th 963- 1008 .217 - 232 3675 , 13th 1009- 1056 .233- 244 3676 ,, 20th 1057 - 1100 .245 - 260 3677 ,, 27th 1101 - 1146 .261 - 276 INDEX TO VOLUME I FOR 1931 READERS in search of a particular subject will find it useful to bear in mind that the references are in several cases distributed under two or more separate -

Edinburgh Suffragists: Exercising the Franchise at Local Level1

EDINBURGH SUFFRAGISTS: EXERCISING THE FRANCHISE AT LOCAL LEVEL1 Esther Breitenbach Key to principal women’s and political organisations ENSWS Edinburgh National Society for Women’s Suffrage ESEC Edinburgh Society for Equal Citizenship EWCA Edinburgh Women Citizens Association SFWSS Scottish Federation of Women’s Suffrage Societies WSPU Women’s Social and Political Union WFL Women’s Freedom League ILP Independent Labour Party SCWCA Scottish Council of Women Citizens Associations SWLF Scottish Women’s Liberal Federation NUSEC National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship ESU Edinburgh Social Union Introduction In the centenary year, the focus of commemoration was, of course, the parliamentary franchise. Yet this he year 2018 witnessed widespread celebrations was never the sole focus of suffrage campaigners’ Tacross the UK of the centenary of the partial activities. They sought to extend women’s rights in parliamentary enfranchisement of women in 1918. In many ways, through a variety of organisations and Scotland this meant ‘women 30 years or over who were campaigns, often inter-related and with overlapping themselves, or their husbands, occupiers as owners or memberships. Of particular importance were the tenants of lands or premises in their constituency in forms of franchise to which women were admitted which they claimed the vote’.2 A woman could also prior to 1918, and the ways in which women be registered if her husband was a local government responded to opportunities to vote and to seek public elector; the local government franchise in Scotland office at local level. This local activity should be was more stringent than the first criterion, and this franchise was therefore more restrictive than that seen, however, in the wider context of a suffrage which applied in England and Wales. -

Women Physicians Serving in Serbia, 1915-1917: the Story of Dorothea Maude

MUMJ History of Medicine 53 HISTORY OF MEDICINE Women Physicians Serving in Serbia, 1915-1917: The Story of Dorothea Maude Marianne P. Fedunkiw, BSc, MA, PhD oon after the start of the First World War, hundreds of One country which benefited greatly from their persistence British women volunteered their expertise , as physi - was Serbia. 2 Many medical women joined established cians, nurses, and in some cases simply as civilians groups such as the Serbian Relief Fund 3 units or the Scottish who wanted to help, to the British War Office . The War Women’s Hospital units set up by Scottish physician Dr. SOffice declined their offer, saying it was too dangerous. The Elsie Inglis. 4 Other, smaller, organized units included those women were told they could be of use taking over the duties which came to be known by the names of their chief physi - of men who had gone to the front, but their skills, intelli - cian or their administrators, including Mrs. Stobart’s Unit, gence and energy were not required at the front lines. Lady Paget’s Unit or The Berry Mission . Many of these This did not deter these women. They went on their own. women wrote their own accounts of their service .5 Still other women went over independently. Dr. Dorothea Clara Maude (1879-1959) was just such a woman. Born near Oxford, educated at University of Oxford and Trinity College, Dublin and trained at London’s Royal Free Hospital, she left her Oxford practice in July 1915 to join her first field unit in northern Serbia. -

Family Experiments Middle-Class, Professional Families in Australia and New Zealand C

Family Experiments Middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c. 1880–1920 Family Experiments Middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c. 1880–1920 SHELLEY RICHARDSON Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Richardson, Shelley, author. Title: Family experiments : middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c 1880–1920 / Shelley Richardson. ISBN: 9781760460587 (paperback) 9781760460594 (ebook) Series: ANU lives series in biography. Subjects: Middle class families--Australia--Biography. Middle class families--New Zealand--Biography. Immigrant families--Australia--Biography. Immigrant families--New Zealand--Biography. Dewey Number: 306.85092 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. The ANU.Lives Series in Biography is an initiative of the National Centre of Biography at The Australian National University, ncb.anu.edu.au. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Photograph adapted from: flic.kr/p/fkMKbm by Blue Mountains Local Studies. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents List of Illustrations . vii List of Abbreviations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Introduction . 1 Section One: Departures 1 . The Family and Mid-Victorian Idealism . 39 2 . The Family and Mid-Victorian Realities . 67 Section Two: Arrival and Establishment 3 . The Academic Evangelists . 93 4 . The Lawyers . 143 Section Three: Marriage and Aspirations: Colonial Families 5 . -

125 Years of Women in Medicine

STRENGTH of MIND 125 Years of Women in Medicine Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne Kathleen Roberts Marjorie Thompson Margaret Ruth Sandland Muriel Denise Sturtevant Mary Jocelyn Gorman Fiona Kathleen Judd Ruth Geraldine Vine Arlene Chan Lilian Mary Johnstone Veda Margaret Chang Marli Ann Watt Jennifer Maree Wheelahan Min-Xia Wang Mary Louise Loughnan Alexandra Sophie Clinch Kate Suzannah Stone Bronwyn Melissa Dunbar King Nicole Claire Robins-Browne Davorka Anna Hemetek MaiAnh Hoang Nguyen Elissa Stafford Trisha Michelle Prentice Elizabeth Anne McCarthy Fay Audrey Elizabeth Williams Stephanie Lorraine Tasker Joyce Ellen Taylor Wendy Anne Hayes Veronika Marie Kirchner Jillian Louise Webster Catherine Seut Yhoke Choong Eva Kipen Sew Kee Chang Merryn Lee Wild Guineva Joan Protheroe Wilson Tamara Gitanjali Weerasinghe Shiau Tween Low Pieta Louise Collins Lin-Lin Su Bee Ngo Lau Katherine Adele Scott Man Yuk Ho Minh Ha Nguyen Alexandra Stanislavsky Sally Lynette Quill Ellisa Ann McFarlane Helen Wodak Julia Taub 1971 Mary Louise Holland Daina Jolanta Kirkland Judith Mary Williams Monica Esther Cooper Sara Kremer Min Li Chong Debra Anne Wilson Anita Estelle Wluka Julie Nayleen Whitehead Helen Maroulis Megan Ann Cooney Jane Rosita Tam Cynthia Siu Wai Lau Christine Sierakowski Ingrid Ruth Horner Gaurie Palnitkar Kate Amanda Stanton Nomathemba Raphaka Sarah Louise McGuinness Mary Elizabeth Xipell Elizabeth Ann Tomlinson Adrienne Ila Elizabeth Anderson Anne Margeret Howard Esther Maria Langenegger Jean Lee Woo Debra Anne Crouch Shanti -

Australian Women, Past and Present

Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Edited by Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein and Mary Tomsic Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Diversity in leadership : Australian women, past and present / Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein, Mary Tomsic, editors. ISBN: 9781925021707 (paperback) 9781925021714 (ebook) Subjects: Leadership in women--Australia. Women--Political activity--Australia. Businesswomen--Australia. Women--Social conditions--Australia Other Authors/Contributors: Damousi, Joy, 1961- editor. Rubenstein, Kim, editor. Tomsic, Mary, editor. Dewey Number: 305.420994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Introduction . 1 Part I. Feminist perspectives and leadership 1 . A feminist case for leadership . 17 Amanda Sinclair Part II. Indigenous women’s leadership 2 . Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy: Indigenous women leaders in Yolngu, Australia-wide and international contexts . 39 Gwenda Baker, Joanne Garŋgulkpuy and Kathy Guthadjaka 3 . Aunty Pearl Gibbs: Leading for Aboriginal rights . 53 Rachel Standfield, Ray Peckham and John Nolan Part III. Local and global politics 4 . Women’s International leadership . 71 Marilyn Lake 5 . The big stage: Australian women leading global change . 91 Susan Harris Rimmer 6 . ‘All our strength, all our kindness and our love’: Bertha McNamara, bookseller, socialist, feminist and parliamentary aspirant . -

THE HARVEST of a QUIET EYE.Pdf

li1 c ) 1;: \l} i e\ \. \ .\ The University of Sydney Copyright in relation to this thesis* Unde r the Copyright Act 1968 (several provision of which are referred to below), this thesis must be used only under the normal conditions of scholarly fair dealing for the purposes of research, criticism or review. In particular no results or conclusions should be extracted (rom it, nor should it be copied or closely paraphrased in whole or in part without the written consent of the author. Proper written acknowledgement should be made for any assistance obtained from this thesis. Under Section 35(2) of the Copyright Act 1968 'the .uthor of a literary, dramatic. musical or artistic work is the owner of any copyright subsisting in the work', By virtUe of Section 32( I) copyright 'subsists in an original literary, dramatic. musical or artistic work that is unpublished' and of which the author was an Australian citizen, an Australian protected person or a person resident in Australia. The Act. by Section 36( I) provides: 'Subject to this Act. the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is infringed by a person who. not being the owner of the copyright and without the licence of the owner of the copyright, does in Australia, or authorises the doing in Australia of, any act comprised in the copyright'. Section 31 (I )(.)(i) provides thot copyright includes the exclusive right to'reproduce the work. in a material form'.Thus, copyright is infringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright, reproduces or authorises the reproduction of a work., or of more than a reasonable part of the work, in a material form, unless the reproduction is a 'fair dealing' with the work 'for the purpose of research or swdy' as further defined in Sections 40 and . -

Final Hannah Online Credits

Hannah Gadsby’s Oz – Full Series Credits WRITTEN & PRESENTED BY HANNAH GADSBY ------ DIRECTED & CO-WRITTEN BY MATTHEW BATE ------------ PRODUCED BY REBECCA SUMMERTON ------ EDITOR DAVID SCARBOROUGH COMPOSER & MUSIC EDITOR BENJAMIN SPEED ------ ART HISTORY CONSULTANT LISA SLADE ------ 1 Hannah Gadsby’s Oz – Full Series Credits ARTISTS LIAM BENSON DANIEL BOYD JULIE GOUGH ROSEMARY LAING SUE KNEEBONE BEN QUILTY LESLIE RICE JOAN ROSS JASON WING HEIDI YARDLEY RAYMOND ZADA INTERVIEWEES PROFESSOR CATHERINE SPECK LINDSAY MCDOUGALL ------ PRODUCTION MANAGER MATT VESELY PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS FELICE BURNS CORINNA MCLAINE CATE ELLIOTT RESEARCHERS CHERYL CRILLY ANGELA DAWES RESEARCHER ABC CLARE CREMIN COPYRIGHT MANAGEMENT DEBRA LIANG MATT VESELY CATE ELLIOTT ------ DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY NIMA NABILI RAD SHOOTING DIRECTOR DIMI POULIOTIS SOUND RECORDISTS DAREN CLARKE LEIGH KENYON TOBI ARMBRUSTER JOEL VALERIE DAVID SPRINGAN-O’ROURKE TEST SHOOT SOUND RECORDIST LACHLAN COLES GAFFER ROBERTTO KARAS GRIP HUGH FREYTAG ------ 2 Hannah Gadsby’s Oz – Full Series Credits TITLES, MOTION GRAPHICS & COLOURIST RAYNOR PETTGE DIALOGUE EDITOR/RE-RECORDING MIXER PETE BEST SOUND EDITORS EMMA BORTIGNON SCOTT ILLINGWORTH PUBLICITY STILLS JONATHAN VAN DER KNAPP ------ TOKEN ARTISTS MANAGING DIRECTOR KEVIN WHTYE ARTIST MANAGER ERIN ZAMAGNI TOKEN ARTISTS LEGAL & BUSINESS CAM ROGERS AFFAIRS MANAGER ------ ARTWORK SUPPLIED BY: Ann Mills Art Gallery New South Wales Art Gallery of Ballarat Art Gallery of New South Wales Art Gallery of South Australia Australian War Memorial, Canberra -

Dr Agnes Lloyd Bennett Died in 1960, Her Heroism Almost Totally Forgotten

U3A AUSTRALIAN HISTORY. Dr. AGNES LLOYD BENNETT. 1872-1960. [Editor: When “this story first arrived at my ‘inbox’ I felt that some of the expressions in it were “needing adjustment”, being perhaps not “correct” for our times. I began an editing process, but realized that the actual forms of language used in the story reflect the language of the time and probably of the author in former times. I abandoned the edit and give you the original text. Enjoy both the story and the John’s writing of it.] Agnes Lloyd Bennett was born at Neutral Bay in Sydney on 24 June 1872. She was educated at Abbotsleigh and Sydney Girls High Schools. She won a scholarship and went to Sydney University and wanted to study Medicine but was told that women could not become Doctors so she studied Science and graduated with Honours. She found that she would be welcome to study Medicine at Edinburgh University so she set sail for Scotland. In 1899 she graduated with Honours She now returned to Australia to find that Hospitals would not allow women to be Doctors there. She opened a practice in Darlinghurst but there was much prejudice against a female Doctor and she was forced to close the practice. She was accepted by women but some men would not allow their wives and daughters to see a woman Doctor. The only place that she was accepted was at Callan Park Hospital for the Insane. 1 In 1905 she went to New Zealand and was offered a position at Wellington, She was soon the Chief Medical Officer at St.