Philip Payton Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE 7 February 2017 Premier awards Tennyson Medal at SACE Merit Ceremony The Premier of South Australia, the Hon. Jay Weatherill MP, awarded the prestigious Tennyson Medal for excellence in English Studies to 2016 Year 12 graduate, Ashleigh Jones at the SACE Merit Ceremony at Government House today. The ceremony, in its twenty-ninth year, saw 996 students awarded with 1302 subject merits for outstanding achievement in SACE Stage 2 subjects. Subject merits are awarded to students who gain an overall subject grade of A+ and demonstrate exceptional achievement in that subject. As part of the Merit Ceremony, His Excellency the Hon. Hieu Van Le AC, the Governor of South Australia, presented the following awards: Governor of South Australia Commendation for outstanding overall achievement in the SACE (twenty-five recipients in 2016) Governor of South Australia Commendation — Aboriginal Student SACE Award for the Aboriginal student with the highest overall achievement in the SACE Governor of South Australia Commendation – Excellence in Modified SACE Award for the student with an identified intellectual disability who demonstrates outstanding achievement exclusively through SACE modified subjects. The Tennyson Medal dates back to 1901 when the former Governor of South Australia, Lord Tennyson, established the Tennyson Medal to encourage the study of English literature. The long list of recipients includes the late John Bannon AO, 39th Premier of South Australia, who was awarded the medal in 1961. For her Year 12 English Studies, Ashleigh studied works by Henrik Ibsen (A Doll’s House), Zhang Yimou who directed Raise the Red Lantern, and Tennessee Williams (The Glass Menagerie). -

The University of Exeter<Br>

News from the Universities The University of Exeter Initiatives in local, regional and community history The University of Exeter now operates on two separate campuses, Streatham Campus in Exeter and, since 2005, Tremough Campus near Falmouth, Cornwall. History at Exeter has expanded considerably in the last decade, partly as a result of the opening of the Tremough campus. There are now 27 full-time staff based at Streatham and another 10 in Tremough, with research interests extending from early Medieval Britain to post- Communist Eastern Europe. In the last five years there has also been a considerable intensification of activity in local and regional history, as History has sought to forge links with local community groups, institutions and other charitable and business organisations. In many respects staff at Tremough have taken the lead in developing these connections. A strong civic dimension has been developed within the History cluster at Tremough, with significant engagement with the Cornish community at a variety of levels. This was based initially on the long-standing work of the Institute of Cornish Studies, part of the University of Exeter but part-funded by Cornwall Council, and located in Cornwall well before the establishment of the Cornwall Campus. Since the early 1990s, the Institute has focused on issues of identity in modern Cornwall, which it has explored through a variety of methods—for example, biography, demography and oral history—and which has led among other things to the establishment of strong links with the overseas Cornish diaspora and to the publication of the annual volume Cornish Studies (University of Exeter Press). -

2017 Annual Report ABOUT DON

2017 Annual Report ABOUT DON Don Dunstan was one of Australia’s most charismatic, courageous, and visionary politicians; a dedicated reformer with a deep commitment to social justice, a true friend to the Aboriginal people and those newly arrived in Australia, and with a lifelong passion for the arts and education. He took positive steps to enhance the status of women. Most of his reforms have withstood the test of time and ‘We have faltered in our quest to many have been strengthened with time. Many of his reforms in sex discrimination, Aboriginal land rights provide better lives for all our and consumer protection were the first of their kind in citizens, rather than just for the Australia. talented, lucky groups. To regain He was a leading campaigner for immigration reform and our confidence in our power to was instrumental in the elimination of the White Australia shape the society in which we live, Policy. He was instrumental in social welfare and child protection reforms, consumer protection, Aboriginal and to replace fear and just land rights, urban planning, heritage protection, anti- coping with shared joy, optimism discrimination laws, abolition of capital punishment, and mutual respect, needs new environment protection and censorship. imagining and thinking and learning from what succeeds elsewhere.’ The Hon. Don Dunstan AC QC 2 CONTENTS NOTE: The digital copy of this report contains hyperlinks. These include the page numbers below, some images, and social media links throughout the report. 2 About Don 11 Art4Good Fund 4 Chair’s Report 12 Thinkers in Residence 5 Achievements 16 Adelaide Zero Project 6 Governance and Staff 19 Media Coverage Advisory Boards, Donate and Volunteer 7 Interns & Volunteers 20 8 Events 21 Financial Report 10 Scholarships 3 CHAIR’S REPORT In 2017 we celebrated 50 years since Don Dunstan first became Premier. -

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia Clare Parker BMusSt, BA(Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Discipline of History, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. August 2013 ii Contents Contents ii Abstract iv Declaration vi Acknowledgements vii List of Abbreviations ix List of Figures x A Note on Terms xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: ‘The Practice of Sound Morality’ 21 Policing Abortion and Homosexuality 24 Public Conversation 36 The Wowser State 44 Chapter 2: A Path to Abortion Law Reform 56 The 1930s: Doctors, Court Cases and Activism 57 World War II 65 The Effects of Thalidomide 70 Reform in Britain: A Seven Month Catalyst for South Australia 79 Chapter 3: The Abortion Debates 87 The Medical Profession 90 The Churches 94 Activism 102 Public Opinion and the Media 112 The Parliamentary Debates 118 Voting Patterns 129 iii Chapter 4: A Path to Homosexual Law Reform 139 Professional Publications and Prohibited Literature 140 Homosexual Visibility in Australia 150 The Death of Dr Duncan 160 Chapter 5: The Homosexuality Debates 166 Activism 167 The Churches and the Medical Profession 179 The Media and Public Opinion 185 The Parliamentary Debates 190 1973 to 1975 206 Conclusion 211 Moral Law Reform and the Public Interest 211 Progressive Reform in South Australia 220 The Slippery Slope 230 Bibliography 232 iv Abstract This thesis examines the circumstances that permitted South Australia’s pioneering legalisation of abortion and male homosexual acts in 1969 and 1972. It asks how and why, at that time in South Australian history, the state’s parliament was willing and able to relax controls over behaviours that were traditionally considered immoral. -

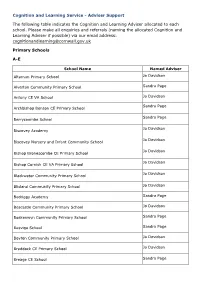

Cognition and Learning Schools List

Cognition and Learning Service - Adviser Support The following table indicates the Cognition and Learning Adviser allocated to each school. Please make all enquiries and referrals (naming the allocated Cognition and Learning Adviser if possible) via our email address: [email protected] Primary Schools A-E School Name Named Adviser Jo Davidson Altarnun Primary School Sandra Page Alverton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Antony CE VA School Sandra Page Archbishop Benson CE Primary School Sandra Page Berrycoombe School Jo Davidson Biscovey Academy Jo Davidson Biscovey Nursery and Infant Community School Jo Davidson Bishop Bronescombe CE Primary School Jo Davidson Bishop Cornish CE VA Primary School Jo Davidson Blackwater Community Primary School Jo Davidson Blisland Community Primary School Sandra Page Bodriggy Academy Jo Davidson Boscastle Community Primary School Sandra Page Boskenwyn Community Primary School Sandra Page Bosvigo School Boyton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Jo Davidson Braddock CE Primary School Sandra Page Breage CE School School Name Named Adviser Jo Davidson Brunel Primary and Nursery Academy Jo Davidson Bude Infant School Jo Davidson Bude Junior School Jo Davidson Bugle School Jo Davidson Burraton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Callington Primary School Jo Davidson Calstock Community Primary School Jo Davidson Camelford Primary School Jo Davidson Carbeile Junior School Jo Davidson Carclaze Community Primary School Sandra Page Cardinham School Sandra Page Chacewater Community Primary -

The Boulton and Watt Archive and the Matthew Boulton Papers from Birmingham Central Library Part 12: Boulton & Watt Correspondence and Papers (MS 3147/3/179)

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION: A DOCUMENTARY HISTORY Series One: The Boulton and Watt Archive and the Matthew Boulton Papers from Birmingham Central Library Part 12: Boulton & Watt Correspondence and Papers (MS 3147/3/179) DETAILED LISTING REEL 199 3/4 Letters to James Watt, 1780 (44 items) Letters from Matthew Boulton to James Watt from 1780. The bundle also contains three letters from Logan Henderson to James Watt. 1. Letter. Matthew Boulton (York) to James Watt (Birmingham). 8 Mar. 1780. Summarised “Concerning the signing of Fenton’s articles. Also the copying business. Boulton going to Newcastle.” 2. Letter. Matthew Boulton (London) to James Watt (—). 6 Apr. 1780. Misdated by Boulton as Mar. Summarised “York Building Water Works require an engine. Smeaton’s failure with wooden piston. Concerning the copying scheme.” 3. Letter. Matthew Boulton (London) to James Watt (Birmingham). “Saturday night” 8 Apr. 1780. On the same sheet: Memorandum. “York Building Western Engine. Query respecting the Erection of a new engine to raise 55,600 cubic feet in 8 hours.” 7 Apr. 1780. Summarised “Calculations of size of York Buildings engine. Dr. Roebuck almost insists that his son becomes partner. Copying scheme.” 4. Letter. Matthew Boulton (London) to James Watt (—). 10 Apr. 1780. Docketed “About Mr. Wiss’s affairs.” Summarised “Copying scheme. York Building Water Works calculations. Concerning dividing money matters.” 5. Letter. Matthew Boulton (London) to James Watt (Birmingham). 17 Apr. 1780. On the same sheet: Letter. James Keir (London) to James Watt (Birmingham). 17 Apr. 1780. Summarised “Letter from Keir with information re. copying scheme, and the naval metal. -

Cusgarne School This Week

CUSGARNE SCHOOL THIS WEEK Date: 8th June 2018 Diary Dates Dear All Welcome back! This week has been an exciting one for the children— w/c 11 June Class 3 have been on camp to London, Class 2 have had a visit to a mine Phonics Screening and Class 1 have been exploring their new classroom and making good week use of their outdoor space. 12 June Next week will be equally busy—especially for Class 1. Phonics Screening Class photos will take place next week and on Tuesday and Thursday, they welcome the September starters who will be coming in for a taster session. 13 June On Tuesday, Tempest are coming into school for the class photos so Minack Trip please don’t be late and wear your smartest uniform! On Wednesday the whole school will be going to the Minack to see Dr 14 June Doolittle. This is a non uniform day but please check the forecast before- TRLC awards hand. If it is forecast to be sunny, wear plenty of suncream since the after- noon sun does fall onto the Minack. Hats and suncream to the ready! We 15 June are grateful to the Friends for helping us fund this trip and for supplying the Dress down day interval ice-creams. Please remember that there are no music lessons or (donations for after school clubs next Wednesday and we are returning to school at tombola) approximately 5.30pm. Friday the 15th will also be a non-uniform day and we are asking that the 18 June children bring in a small donation of a gift for the tombola. -

Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018

AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW Parliament in the Periphery: Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018* Mark Dean Research Associate, Australian Industrial Transformation Institute, Flinders University of South Australia * Double-blind reviewed article. Abstract This article examines the sixteen years of Labor government in South Australia from 2002 to 2018. With reference to industry policy and strategy in the context of deindustrialisation, it analyses the impact and implications of policy choices made under Premiers Mike Rann and Jay Weatherill in attempts to progress South Australia beyond its growing status as a ‘rustbelt state’. Previous research has shown how, despite half of Labor’s term in office as a minority government and Rann’s apparent disregard for the Parliament, the executive’s ‘third way’ brand of policymaking was a powerful force in shaping the State’s development. This article approaches this contention from a new perspective to suggest that although this approach produced innovative policy outcomes, these were a vehicle for neo-liberal transformations to the State’s institutions. In strategically avoiding much legislative scrutiny, the Rann and Weatherill governments’ brand of policymaking was arguably unable to produce a coordinated response to South Australia’s deindustrialisation in a State historically shaped by more interventionist government and a clear role for the legislature. In undermining public services and hollowing out policy, the Rann and Wethearill governments reflected the path dependency of responses to earlier neo-liberal reforms, further entrenching neo-liberal responses to social and economic crisis and aiding a smooth transition to Liberal government in 2018. INTRODUCTION For sixteen years, from March 2002 to March 2018, South Australia was governed by the Labor Party. -

Annual Report 2004-2005

Annual Report 2004/2005 Governing partners Supported by Contents Report from the Chair of Trustees 4 Summary of Activities: “There is still much to be done” 6 Foundation Year in Review 10 Trustees’ Report 22 • Statement of Financial Performance 23 • Statement of Financial Position 24 • Statement of Cash Flows 25 • Notes to the Financial Statements 26 • Declaration by Trustees 35 • Independent Audit Report 36 Trustees, Board and Staff 38 Our supporters 40 The Annual Report Published March 2006 By the Don Dunstan Foundation Level 3, 10 Pulteney Street The University of Adelaide, SA 5005 http://www.dunstan.org.au ABN 71 448 549 600 Don Dunstan Foundation Annual Report 2004/2005 Page 2/40 Don Dunstan Foundation Values • Respect for fundamental human rights • Celebration of cultural and ethnic diversity • Freedom of individuals to control their lives • Just distribution of global wealth • Respect for indigenous people and protection of their rights • Democratic and inclusive forms of governance Strategic Directions • Facilitate a productive exchange between academic researchers and Government policy makers • Invigorate policy debate and responses • Consolidate and expand the Foundation’s links with the wider community • Support Chapter activities • Build and maintain the long-term viability of the Foundation Don Dunstan Foundation Annual Report 2004/2005 Page 3/40 REPORT FROM THE CHAIR The financial year 2004/2005 has been extremely productive with the Foundation continuing its drive to implement its Strategic Directions and Strategic Business Plan. The Foundation has provided an array of targeted events, pursued key projects of community benefit, enhanced its infrastructure and promoted its contribution to the wider South Australian Community. -

John Curtin's War

backroom briefings John Curtin's war CLEM LLOYD & RICHARD HALL backroom briefings John Curtin's WAR edited by CLEM LLOYD & RICHARD HALL from original notes compiled by Frederick T. Smith National Library of Australia Canberra 1997 Front cover: Montage of photographs of John Curtin, Prime Minister of Australia, 1941-45, and of Old Parliament House, Canberra Photographs from the National Library's Pictorial Collection Back cover: Caricature of John Curtin by Dubois Bulletin, 8 October 1941 Published by the National Library of Australia Canberra ACT 2600 © National Library of Australia 1997 Introduction and annotations © Clem Lloyd and Richard Hall Every reasonable endeavour has been made to contact relevant copyright holders of illustrative material. Where this has not proved possible, the copyright holders are invited to contact the publisher. National Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data Backroom briefings: John Curtin's war. Includes index. ISBN 0 642 10688 6. 1. Curtin, John, 1885-1945. 2. World War, 1939-1945— Press coverage—Australia. 3. Journalism—Australia. I. Smith, FT. (Frederick T.). II. Lloyd, C.J. (Clement John), 1939- . III. Hall, Richard, 1937- . 940.5394 Editor: Julie Stokes Designer: Beverly Swifte Picture researcher/proofreader: Tony Twining Printed by Goanna Print, Canberra Published with the assistance of the Lloyd Ross Forum CONTENTS Fred Smith and the secret briefings 1 John Curtin's war 12 Acknowledgements 38 Highly confidential: press briefings, June 1942-January 1945 39 Introduction by F.T. Smith 40 Chronology of events; Briefings 42 Index 242 rederick Thomas Smith was born in Balmain, Sydney, Fon 18 December 1904, one of a family of two brothers and two sisters. -

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other Accounts of Constitution-Makers, Constitutions and Citizenship

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other accounts of constitution-makers, constitutions and citizenship This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2005 Geoffrey Trenorden BA Honours (Murdoch) Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………….. Geoffrey Trenorden ii Abstract As argued throughout this thesis, in his personification of the federal story, if not immediately in his formulation of its paternity, Deakin’s unpublished memoirs anticipated the way that federation became codified in public memory. The long and tortuous process of federation was rendered intelligible by turning it into a narrative set around a series of key events. For coherence and dramatic momentum the narrative dwelt on the activities of, and words of, several notable figures. To explain the complex issues at stake it relied on memorable metaphors, images and descriptions. Analyses of class, citizenship, or the industrial confrontations of the 1890s, are given little or no coverage in Deakinite accounts. Collectively, these accounts are told in the words of the victors, presented in the images of the victors, clothed in the prejudices and predilections of the victors, while the losers are largely excluded. Those who spoke out against or doubted the suitability of the constitution, for whatever reason, have largely been removed from the dominant accounts of constitution-making. More often than not they have been ‘character assassinated’ or held up to public ridicule by Alfred Deakin, the master narrator of the Conventions and federation movement and by his latter-day disciples. -

In the Public Interest

In the Public Interest 150 years of the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office Peter Yule Copyright Victorian Auditor-General’s Office First published 2002 This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without prior written permission. ISBN 0 7311 5984 5 Front endpaper: Audit Office staff, 1907. Back endpaper: Audit Office staff, 2001. iii Foreword he year 2001 assumed much significance for the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office as Tit marked the 150th anniversary of the appointment in July 1851 of the first Victorian Auditor-General, Charles Hotson Ebden. In commemoration of this major occasion, we decided to commission a history of the 150 years of the Office and appointed Dr Peter Yule, to carry out this task. The product of the work of Peter Yule is a highly informative account of the Office over the 150 year period. Peter has skilfully analysed the personalities and key events that have characterised the functioning of the Office and indeed much of the Victorian public sector over the years. His book will be fascinating reading to anyone interested in the development of public accountability in this State and of the forces of change that have progressively impacted on the powers and responsibilities of Auditors-General. Peter Yule was ably assisted by Geoff Burrows (Associate Professor in Accounting, University of Melbourne) who, together with Graham Hamilton (former Deputy Auditor- General), provided quality external advice during the course of the project.