The Banning of E.A.H. Laurie at Melbourne Teachers' College, 1944

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Politics in Victoria: the Impact of Legislative Design, Policy

Water Politics in Victoria The impact of legislative design, policy objectives and institutional constraints on rural water supply governance Benjamin David Rankin Thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Swinburne Institute for Social Research Faculty of Health, Arts and Design Swinburne University of Technology 2017 i Abstract This thesis explores rural water supply governance in Victoria from its beginnings in the efforts of legislators during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to shape social and economic outcomes by legislative design and maximise developmental objectives in accordance with social liberal perspectives on national development. The thesis is focused on examining the development of Victorian water governance through an institutional lens with an intention to explain how the origins of complex legislative and administrative structures later come to constrain the governance of a policy domain (water supply). Centrally, the argument is concentrated on how the institutional structure comprising rural water supply governance encouraged future water supply endeavours that reinforced the primary objective of irrigated development at the expense of alternate policy trajectories. The foundations of Victoria’s water legislation were initially formulated during the mid-1880s and into the 1890s under the leadership of Alfred Deakin, and again through the efforts of George Swinburne in the decade following federation. Both regarded the introduction of water resources legislation as fundamentally important to ongoing national development, reflecting late nineteenth century colonial perspectives of state initiated assistance to produce social and economic outcomes. The objectives incorporated primarily within the Irrigation Act (1886) and later Water Acts later become integral features of water governance in Victoria, exerting considerable influence over water supply decision making. -

John Curtin's War

backroom briefings John Curtin's war CLEM LLOYD & RICHARD HALL backroom briefings John Curtin's WAR edited by CLEM LLOYD & RICHARD HALL from original notes compiled by Frederick T. Smith National Library of Australia Canberra 1997 Front cover: Montage of photographs of John Curtin, Prime Minister of Australia, 1941-45, and of Old Parliament House, Canberra Photographs from the National Library's Pictorial Collection Back cover: Caricature of John Curtin by Dubois Bulletin, 8 October 1941 Published by the National Library of Australia Canberra ACT 2600 © National Library of Australia 1997 Introduction and annotations © Clem Lloyd and Richard Hall Every reasonable endeavour has been made to contact relevant copyright holders of illustrative material. Where this has not proved possible, the copyright holders are invited to contact the publisher. National Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data Backroom briefings: John Curtin's war. Includes index. ISBN 0 642 10688 6. 1. Curtin, John, 1885-1945. 2. World War, 1939-1945— Press coverage—Australia. 3. Journalism—Australia. I. Smith, FT. (Frederick T.). II. Lloyd, C.J. (Clement John), 1939- . III. Hall, Richard, 1937- . 940.5394 Editor: Julie Stokes Designer: Beverly Swifte Picture researcher/proofreader: Tony Twining Printed by Goanna Print, Canberra Published with the assistance of the Lloyd Ross Forum CONTENTS Fred Smith and the secret briefings 1 John Curtin's war 12 Acknowledgements 38 Highly confidential: press briefings, June 1942-January 1945 39 Introduction by F.T. Smith 40 Chronology of events; Briefings 42 Index 242 rederick Thomas Smith was born in Balmain, Sydney, Fon 18 December 1904, one of a family of two brothers and two sisters. -

In the Public Interest

In the Public Interest 150 years of the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office Peter Yule Copyright Victorian Auditor-General’s Office First published 2002 This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without prior written permission. ISBN 0 7311 5984 5 Front endpaper: Audit Office staff, 1907. Back endpaper: Audit Office staff, 2001. iii Foreword he year 2001 assumed much significance for the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office as Tit marked the 150th anniversary of the appointment in July 1851 of the first Victorian Auditor-General, Charles Hotson Ebden. In commemoration of this major occasion, we decided to commission a history of the 150 years of the Office and appointed Dr Peter Yule, to carry out this task. The product of the work of Peter Yule is a highly informative account of the Office over the 150 year period. Peter has skilfully analysed the personalities and key events that have characterised the functioning of the Office and indeed much of the Victorian public sector over the years. His book will be fascinating reading to anyone interested in the development of public accountability in this State and of the forces of change that have progressively impacted on the powers and responsibilities of Auditors-General. Peter Yule was ably assisted by Geoff Burrows (Associate Professor in Accounting, University of Melbourne) who, together with Graham Hamilton (former Deputy Auditor- General), provided quality external advice during the course of the project. -

From Charles La Trobe to Charles Gavan Duffy: Selectors, Squatters and Aborigines 3

Journal of the C. J. La Trobe Society Inc. Vol. 7, No. 3, November 2008 ISSN 1447-4026 La Trobeana is kindly sponsored by Mr Peter Lovell LOVELL CHEN ARCHITECTS & HERITAGE CONSULTANTS LOVELL CHEN PTY LTD, 35 LITTLE BOURKE STREET, MELBOURNE 3000, AUSTRALIA Tel +61 (0)3 9667 0800 FAX +61 (0)3 9662 1037 ABN 20 005 803 494 La Trobeana Journal of the C J La Trobe Society Inc. Vol. 7, No. 3, November 2008 ISSN 1447-4026 For contributions contact: The Honorary Editor Dr Fay Woodhouse [email protected] Phone: 0427 042753 For subscription enquiries contact: The Honorary Secretary The La Trobe Society PO Box 65 Port Melbourne, Vic 3207 Phone: 9646 2112 FRONT COVER Thomas Woolner, 1825 – 1892, sculptor Charles Joseph La Trobe 1853, diam. 24.0cm. Bronze portrait medallion showing the left profile of Charles Joseph La Trobe. Signature and date incised in bronze I.I.: T. Woolner. Sc. 1853:/M La Trobe, Charles Joseph, 1801 – 1875. Accessioned 1894 La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria. CONTENTS A Word from the President 1 Call for Assistance – Editorial Committee 1 Forthcoming Events 2 Christmas Cocktails 2 Government House Open Day 2 La Trobe’s Birthday 2009 2 A Word from the Treasurer 2 From Charles La Trobe to Charles Gavan Duffy: selectors, squatters and Aborigines 3 The Walmsley House at Royal Park: La Trobe’s “Other” Cottage 12 Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria 19 A Word from the President It is hard to believe that the year is nearly at an A highlight of the year was the inaugural La end. -

Samuel Griffith Society Proceedings Vol 2

Proceedings of the Second Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Two The Windsor Hotel, Melbourne; 30 July - 1 August 1993 Copyright 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Foreword (P4) John Stone Foreword Dinner Address (P5) The Hon. Jeff Kennett, MLA; Premier of Victoria The Crown and the States Introductory Remarks (P14) John Stone Introductory Chapter One (P15) Dr Frank Knopfelmacher The Crown in a Culturally Diverse Australia Chapter Two (P18) John Hirst The Republic and our British Heritage Chapter Three (P23) Jack Waterford Australia's Aborigines and Australian Civilization: Cultural Relativism in the 21st Century Chapter Four (P34) The Hon. Bill Hassell Mabo and Federalism: The Prospect of an Indigenous People's Treaty Chapter Five (P47) The Hon. Peter Connolly, CBE, QC Should Courts Determine Social Policy? Chapter Six (P58) S E K Hulme, AM, QC The High Court in Mabo Chapter Seven (P79) Professor Wolfgang Kasper Making Federalism Flourish Chapter Eight (P84) The Rt. Hon. Sir Harry Gibbs, GCMG, AC, KBE The Threat to Federalism Chapter Nine (P88) Dr Colin Howard Australia's Diminishing Sovereignty Chapter Ten (P94) The Hon. Peter Durack, QC What is to be Done? Chapter Eleven (P99) John Paul The 1944 Referendum Appendix I (P113) Contributors Appendix II (P116) The Society's Statement of Purposes Published 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society P O Box 178, East Melbourne Victoria 3002 Printed by: McPherson's Printing Pty Ltd 5 Dunlop Rd, Mulgrave, Vic 3170 National Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data: Proceedings of The Samuel Griffith Society Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Two ISBN 0 646 15439 7 Foreword John Stone Copyright 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society. -

2009 Yearbook, Which Coincides with LV’S Experiencebank 30 20Th Anniversary

Leadership Victoria Yearbook 2009 Our Mission Leadership Victoria LEADERSHIP VICTORIA IS AN INNOVATIVE, INDEPENDENT, NOT-FOR-PROFIT ORGANISATION DEVELOPING PEOPLE WHO EXERCISE POSITIVE AND ENDURING LEADERSHIP IN AND FOR THE REAL WORLD. Yearbook 2009 Table of Contents Message from the Chairman 6 Message fron the Executive DIrector 8 A Letter to Hugh Williamson 10 Williamson Community Leadership Program 14 WCLP – 2009 Fellows 16 WCLP and the Victorian Bushfire Reconstruction and Recovery Authority 26 Welcome to the Leadership Victoria (LV) WCLP – 2009 Guest Speakers 28 2009 Yearbook, which coincides with LV’s ExperienceBank 30 20th Anniversary. ExperienceBank — 2009 Guest Speakers 37 This publication serves to recognise individuals Praise for ExperienceBank 38 graduating from our Williamson Community SkillsBank 41 Leadership and ExperienceBank programs. Praise for SkillsBank 42 It also highlights some of the achievements Organisations supported by LV 44 made through LV’s community engagement LV Alumni 46 programs: ExperienceBank and SkillsBank. LV Council Members 2009 60 These formal programs help meet the needs LV Alumni Representitive Group of community organisations by matching skilled Convenor’s Report 2009 63 LV Alumni to specific projects, and enabling LV Staff 64 our Alumni to enhance the wellbeing and Our Sponsors 66 development of the broader community. Thank You 67 We warmly welcome the current graduates of the Williamson Community Leadership Program and the 2008 ExperienceBank programs as Alumni of LV. 5 Message from the Chairman Garry Ringwood I am pleased to congratulate and welcome our 2009 is the 20th Anniversary of Leadership Victoria 2009 Alumni — this year’s Williamson Community and while that is significant, this year also marks the Leadership Fellows and ExperienceBank Associates. -

Earle Page and the Imagining of Australia

‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA ‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA STEPHEN WILKS Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for? Robert Browning, ‘Andrea del Sarto’ The man who makes no mistakes does not usually make anything. Edward John Phelps Earle Page as seen by L.F. Reynolds in Table Talk, 21 October 1926. Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463670 ISBN (online): 9781760463687 WorldCat (print): 1198529303 WorldCat (online): 1198529152 DOI: 10.22459/NPM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This publication was awarded a College of Arts and Social Sciences PhD Publication Prize in 2018. The prize contributes to the cost of professional copyediting. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Earle Page strikes a pose in early Canberra. Mildenhall Collection, NAA, A3560, 6053, undated. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Illustrations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Abbreviations . xiii Prologue: ‘How Many Germans Did You Kill, Doc?’ . xv Introduction: ‘A Dreamer of Dreams’ . 1 1 . Family, Community and Methodism: The Forging of Page’s World View . .. 17 2 . ‘We Were Determined to Use Our Opportunities to the Full’: Page’s Rise to National Prominence . -

Fay Woodhouse.Pdf

fTS MCLJ\lU~N COLL. J24.294 09":' 5 woo THE 1951 COMMUNIST PARTY DISSOLUTION REFERENDUM DEBATE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE Fay Woodhouse Fourth Year Honours Thesis Faculty of Arts, Victoria University of Technology October, 1996 DISCLAIMER This thesis is the product of my own original research and has not been previously submitted for academic accreditation. Fay Woodhouse 25 October 1996 To the best of my knowledge and belief, the above statements are true. DJ Markwell Visiting Professor of Political Science Supervisor SYNOPSIS This thesis outlines the debate on the 1951 Communist Party Dissolution Referendum at the University of Melbourne and considers how this casts light on Australia's social, political and higher education institutions at the time. Firstly, it provides a background to the fight against communism in Australia whicll was accelerated by the onset of the Cold War. The series of events which finally led to the calling of the referendum, and the referendum campaign itself are outlined as a backdrop to the particular debate under consideration. Secondly, it looks at the University's place in society at the time, and particularly how the community viewed political activity by prominent figures from the relatively secluded world of the University. Finally, it attempts to analyse the impact of the University's contribution to the public debate, in light of the referendum's failure. In a Cold War context, it assesses the University's susceptibility to Government criticism, and the very real pressures felt by the leadership of the University to ensure its integrity. In the final analysis, the study reveals a rich tapestry of events woven into the history of the University of Melbourne . -

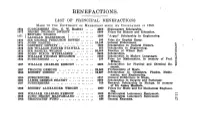

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE to the UNIVERSITY Oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION in 1853

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE TO THE UNIVERSITY oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853. 1864 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec, G. W. Rusden) .. .. £866 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 6000 Prizes for History and Education. 1871 j LA^HL^MACKmNON I 100° "ArSUS" S«h°lar8hiP ln Engineering. 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN 100 Prize for English Essay. 1873 JOHN HASTIE 19,140 General Endowment. 1873 GODFREY HOWITT 1000 Scholarships in Natural History. 1873 SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL 666 Scholarship in Engineering. 1876 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30,000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON 6000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. 1884 SUBSCRIBERS 160 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 2000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Re search. 1887 FRANCIS ORMOND 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,887 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathe matics, and Engineering. 1890 SUBSCRIBERS 6217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY 8900 Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology. 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 760 Research Scholarship In Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT 1000 Prizes for Music and for Mechanical Engineer ing. 1902 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 1000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 GRADUATES' FUND 466 General Expenses. BENEFACTIONS (Continued). 1908 TEACHING STAFF £1160 General Expenses. oo including Professor Sponcer £2riS Professor Gregory 100 Professor Masson 100 1908 SUBSCRIBERS 106 Prize in memory of Alexander Sutherland. 1908 GEORGE McARTHUR Library of 2600 Books. 1004 DAVID KAY 6764 Caroline Kay Scholarship!!. 1904-6 SUBSCRIBERS TO UNIVERSITY FUND . -

NUI MAYNOOTH Imperial Precedents in the Home Rule Debates, 1867

NUI MAYNOOTH Ollscoil na hÉlreann MA Nuad Imperial precedents in the Home Rule Debates, 1867-1914 by Conor Neville THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF MLITT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Supervisor of Research: Prof. Jacqueline Hill February, 2011 Imperial precedents in the Home Rule Debates, 1867-1914 by Conor Neville 2011 THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF MLITT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Contents Acknowledgements iii Abbreviations iv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Taking their cues from 1867: Isaac Butt and Home Rule in the 1870s 16 Chapter 2: Tailoring their arguments: The Home Rule party 1885-1893 60 Chapter 3: The Redmondite era: Colonial analogies during the Home Rule crisis 110 Conclusion 151 Bibliography 160 ii Acknowledgements I wish to thank both the staff and students of the NUI Maynooth History department. I would like, in particular, to record my gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Jacqueline Hill for her wise advice and her careful and forensic eye for detail at all times. I also wish to thank the courteous staff in the libraries which I frequented in NUI Maynooth, Trinity College Dublin, University College Dublin, the National Libraiy of Ireland, the National Archives, and the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland. I want to acknowledge in particular the help of Dr. Colin Reid, who alerted me to the especially revelatory Irish Press Agency pamphlets in the National Library of Ireland. Conor Neville, 27 Jan. 2011 iil Abbreviations A. F. I. L. All For Ireland League B. N. A. British North America F. J. Freeman’s Journal H. -

Philip Payton Contents

Labor and the Radical Tradition in South Australia Philip Payton Contents Foreword – Hon. Jay Weatherill vii Labor or Labour? x Preface xi PART ONE RADICAL TRADITIONS 1 Radical Traditions – South Australia 3 2 Radical Traditions – The Cornish at Home and Abroad 25 PART TWO COPPER AND ORGANISED LABOR 3 1848 and All That – Antipodean Chartists? 55 4 Moonta, Wallaroo and the Rise of Trade Unionism 75 PART THREE RISE AND FALL 5 Towards Parliamentary Representation 121 6 Labor in Power – Tom Price and John Verran 152 7 Labor and the Conscription Crisis 187 8 Between the Wars 222 PART FOUR THE NATURAL PARTY OF GOVERNMENT? 9 The Dunstan Era 261 10 Life After Dunstan – To Bannon and Beyond 290 Epilogue 306 Notes 310 Index 349 Foreword The election, in May 1891, of Richard ‘Dicky’ Hooper – a Cornish miner from Moonta – as the first Labor MP in State Parliament might have represented a shock to the political establishment of South Australia. But his historic victory, in fact, resulted from the inception and steady growth of a determined and well-organised local labor movement – one that owed much of its origins to the zeal of Cornish copper miners who settled in the Mid North and on Yorke Peninsula during the early decades of the colony. As Philip Payton explains in this meticulously researched and superbly told story, among the many cultural traditions the Cornish brought with them was a belief in education and self-improvement, a deep devotion to the Methodist faith and an oftentimes fiery attachment to radical politics. In their vii adopted home of South Australia, these traits helped create an embryonic trade union movement and, in turn, led to the formation of the forerunner of today’s Labor Party. -

Copyright by Rhonda Leann Evans Case 2004

Copyright by Rhonda Leann Evans Case 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Rhonda Leeann Evans Case Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Politics and Law of Anglo-American Antidiscrimination Regimes, 1945-1995 Committee: John C. Higley, Supervisor Gary P. Freeman H.W. Perry Sanford Levinson Jeffrey K. Tulis The Politics and Law of Anglo-American Antidiscrimination Regimes, 1945-1995 by Rhonda Leann Evans Case, B.A, J.D. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2004 To my Mom and Reed, and in memory of my Father Acknowledgements This dissertation is the product of considerable personal sacrifice not only on my part but, more importantly, on the part of the people I love most. I, therefore, humbly dedicate it to my mother and my husband, for their abiding love and support, and to my father, who sadly did not live to see the project’s completion. I also thank Marcella Evans, who made it easier for me to be so far away from home during such trying times. In addition, I benefited from the support of a tremendous circle of friends who were always there when I needed them: Tracy McFarland, Brenna Troncoso, Rosie and Scott Truelove, Anna O. Law, Holly Hutyera, Pam Wilkins Connelly, John Hudson, Jason Pierce, Emily Werlein, Greg Brown, and Lori Dometrovich. While in Australia and New Zealand, I benefited from the kindnesses of far too many people to list here, but I extend a special thanks to Imogen, Baghurst, Kerri Weeks, Sonia Palmieri, Robyn Lui, Ling Lee, and Peter Barger.