Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bcsfazine #528 | Felicity Walker

The Newsletter of the British Columbia Science Fiction Association #528 $3.00/Issue May 2017 In This Issue: This and Next Month in BCSFA..........................................0 About BCSFA.......................................................................0 Letters of Comment............................................................1 Calendar...............................................................................6 News-Like Matter..............................................................11 Turncoat (Taral Wayne)....................................................17 Art Credits..........................................................................18 BCSFAzine © May 2017, Volume 45, #5, Issue #528 is the monthly club newsletter published by the British Columbia Science Fiction Association, a social organiza- tion. ISSN 1490-6406. Please send comments, suggestions, and/or submissions to Felicity Walker (the editor), at felicity4711@ gmail .com or Apartment 601, Manhattan Tower, 6611 Coo- ney Road, Richmond, BC, Canada, V6Y 4C5 (new address). BCSFAzine is distributed monthly at White Dwarf Books, 3715 West 10th Aven- ue, Vancouver, BC, V6R 2G5; telephone 604-228-8223; e-mail whitedwarf@ deadwrite.com. Single copies C$3.00/US$2.00 each. Cheques should be made pay- able to “West Coast Science Fiction Association (WCSFA).” This and Next Month in BCSFA Friday 19 May: Submission deadline for June BCSFAzine (ideally). Sunday 14 May at 7 PM: May BCSFA meeting—at Ray Seredin’s, 707 Hamilton Street (recreation room), New Westminster. -

Dr Who Pdf.Pdf

DOCTOR WHO - it's a question and a statement... Compiled by James Deacon [2013] http://aetw.org/omega.html DOCTOR WHO - it's a Question, and a Statement ... Every now and then, I read comments from Whovians about how the programme is called: "Doctor Who" - and how you shouldn't write the title as: "Dr. Who". Also, how the central character is called: "The Doctor", and should not be referred to as: "Doctor Who" (or "Dr. Who" for that matter) But of course, the Truth never quite that simple As the Evidence below will show... * * * * * * * http://aetw.org/omega.html THE PROGRAMME Yes, the programme is titled: "Doctor Who", but from the very beginning – in fact from before the beginning, the title has also been written as: “DR WHO”. From the BBC Archive Original 'treatment' (Proposal notes) for the 1963 series: Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/doctorwho/6403.shtml?page=1 http://aetw.org/omega.html And as to the central character ... Just as with the programme itself - from before the beginning, the central character has also been referred to as: "DR. WHO". [From the same original proposal document:] http://aetw.org/omega.html In the BBC's own 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 14 November 1963), both the programme and the central character are called: "Dr. Who" On page 7 of the BBC 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 21 November 1963) there is a short feature on the new programme: Again, the programme is titled: "DR. WHO" "In this series of adventures in space and time the title-role [i.e. -

JULY 2017 Issue 4 the Newsletter of the UK Section of IFFR

JULY 2017 Issue 4 The Newsletter of the UK Section of IFFR The Rotating Beacon The main ingredients of a breath taking fly-in Enjoy our reports inside from around UK, Europe and USA Help us make you’re membership to IFFR awesome. There still are some fly-ins to attend, What about helping us to make your flying a brilliant experience? Take our survey on page 21. You provide the transport, we provide the refreshments and the sights! In this Issue Letter from the Chairman New members survey Turweston Trip 30 second up date International Fly-In’s Diary of events Flyer of the year Award 2016 My favourite city Contents Letter from the chairman 3 Flyer of the year 20 Turweston trip 5 Iffr clothing 21 Ist international fly in of 2017 8 Member questionnaire 21 Oostende 10 Continental co-ordination 22 Membership information 14 IFFR Atlanta flyout 24 Membership application form 15 30 Second up date 26 My favourite city 16 Diary of events 27 Chester report 18 Contact details 28 “A letter from the David centre, with our top table guests at the Christmas Chairmanlunch ” This is my first letter as Chairman and Turweston, my first as Chairman, was what a time I have had so far. I want very well represented and a great to begin by saying thank you to all opportunity for me to meet members the members of the current committee & guests. (See report). The visit to for their support and encouragement Conington was on a beautiful day and they have given to me and also for it was very nice to see three planes from the work that many of them are doing the Isle of Wight. -

The Hinchcliffe/Holmes Era of Doctor Who (1975-77) Matt Hills

‘Gothic’ Body Parts in a ‘Postmodern’ Body of Work? The Hinchcliffe/Holmes Era of Doctor Who (1975-77) Matt Hills (1) The names Philip Hinchcliffe and Robert Holmes may not be greatly familiar to many academic readers of this volume, unless, that is, they also happen to be fans of the (1963-1989, 1996, 2005-) BBC TV series Doctor Who. Hinchcliffe was the producer of this series on all episodes originally transmitted in the UK between 25/1/1975 and 2/4/77, while Holmes was script editor on all material broadcast between 28/12/74 and 17/12/77. However, he went un-credited in this role on stories where he was named as writer, due to BBC regulations which forbade script editors to commission from themselves (see Howe and Walker, 1998). In story terms, Philip Hinchcliffe produced ‘The Ark in Space’ through to ‘The Talons of Weng-Chiang’, whilst Holmes script-edited stories running from ‘Robot’ through to ‘The Sun Makers’ (1977). Under Hinchcliffe as producer, Holmes also wrote ‘The Ark in Space’, ‘The Deadly Assassin’ and ‘The Talons of Weng-Chiang’, and effectively wrote, or at least heavily reworked, ‘The Pyramids of Mars’ and ‘The Brain of Morbius’ (on-screen, these were attributed to the pseudonyms Stephen Harris and Robin Bland). Today, Philip Hinchcliffe is a regular contributor to DVD commentaries and features accompanying ‘his’ Doctor Who stories. Robert Holmes passed away on 24th May, 1986: his overall contribution to Doctor Who is the subject of a documentary on the DVD release of the (1985) story ‘The Two Doctors’. -

Bcsfazine #442 • Felicity Walker

The Newsletter of the British Columbia Science Fiction Association #442 $3.00/Issue March 2010 i In This Issue: This Month in BCSFA.........................................................0 Letters of Comment............................................................1 Calendar...............................................................................4 News-Like Matter...............................................................15 Why Time Travel Sucks....................................................18 Media File...........................................................................21 Upcoming Nifty Film Projects..........................................22 Ask Mr. Guess-It-All!.........................................................23 Zines Received..................................................................24 E-Zines Received..............................................................24 About BCSFA....................................................................26 Why You Got This.............................................................26 BCSFAzine © March 2010, Volume 38, #3, Issue #442 is the monthly club newslet- ter published by the British Columbia Science Fiction Association, a social organiza- tion. ISSN 1490-6406. Please send comments, suggestions, and/or submissions to Felicity Walker (the editor), at felicity4711@ gmail .com or #209–3851 Francis Road, Richmond, BC, Canada, V7C 1J6. BCSFAzine solicits electronic submissions and black-and-white line illustrations in JPG, GIF, BMP, or PSD format, and -

Archived in ANU Research Repository

Archived in ANU Research repository http://www.anu.edu.au/research/access/ This is the accepted version published as: Orthia, Lindy Antirationalist critique or fifth column of scientism? Challenges from Doctor Who to the mad scientist trope Public Understanding of Science 20.4 (2011): pp. 525-542 The final, definitive version of this paper has been published in Public Understanding of Science, 20/4, July/2011 by SAGE Publications Ltd. All rights reserved. © The Author(s), 2010. Reprints and permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/0963662509355899 Deposited ANU Research repository 1 Antirationalist critique or fifth column of scientism? Challenges from Doctor Who to the mad scientist trope Lindy A. Orthia Much of the public understanding of science literature dealing with fictional scientists claims that scientist villains by their nature embody an antiscience critique. I characterize this claim and its founding assumptions as the “mad scientist” trope. I show how scientist villain characters from the science fiction television series Doctor Who undermine the trope via the program’s use of rhetorical strategies similar to Gilbert and Mulkay’s empiricist and contingent repertoires, which define and patrol the boundaries between “science” and “non-science”. I discuss three such strategies, including the literal framing of scientist villains as “mad.” All three strategies exclude the characters from science, relieve science of responsibility for their villainy, and overtly or covertly contribute to the delivery of pro-science messages consistent with rationalist scientism. I focus on scientist villains from the most popular era of Doctor Who, the mid 1970s, when the show embraced the gothic horror genre. -

Doctor Who Classic Touches Down on Boxing Day

DOCTOR WHO CLASSIC TOUCHES DOWN ON BOXING DAY London, 20 December 2019: BritBox Becomes Home to Doctor Who Classic on 26th December Doctor Who fans across the land get ready to clear their schedules as the biggest Doctor Who Classic collection ever streamed in the UK launches on BritBox from Boxing Day. From 26th December, 627 pieces of Doctor Who Classic content will be available on the service. This tally is comprised of a mix of episodes, spin-offs, documentaries, telesnaps and more and includes many rarely-seen treasures. Subscribers will be able to access this content via web, mobile, tablet, connected TVs and Chromecast. 129 complete stories, which totals 558 episodes spanning the first eight Doctors from William Hartnell to Paul McGann, form the backbone of the collection. The collection also includes four complete stories; The Tenth Planet, The Moonbase, The Ice Warriors and The Invasion, which feature a combination of original content and animation and total 22 episodes. An unaired story entitled Shada which was originally presented as six episodes (but has been uploaded as a 130 minute special), brings this total to 28. A further two complete, solely animated stories - The Power Of The Daleks and The Macra Terror (presented in HD) - add 10 episodes. Five orphaned episodes - The Crusade (2 parts), Galaxy 4, The Space Pirates and The Celestial Toymaker - bring the total up to 600. Doctor Who: The Movie, An Unearthly Child: The Pilot Episode and An Adventure In Space And Time will also be available on the service, in addition to The Underwater Menace, The Wheel In Space and The Web Of Fear which have been completed via telesnaps. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...........................................................................................................................5 Table of Contents ..............................................................................................................................7 Foreword by Gary Russell ............................................................................................................9 Preface ..................................................................................................................................................11 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................13 Chapter 1 The New World ............................................................................................................16 Chapter 2 Daleks Are (Almost) Everywhere ........................................................................25 Chapter 3 The Television Landscape is Changing ..............................................................38 Chapter 4 The Doctor Abroad .....................................................................................................45 Sidebar: The Importance of Earnest Videotape Trading .......................................49 Chapter 5 Nothing But Star Wars ..............................................................................................53 Chapter 6 King of the Airwaves .................................................................................................62 -

Doctor Who and the Early Modern World Episode 5: Special Episode - Doctor Who

Doctor Who and the early modern world Episode 5: Special Episode - Doctor Who Deletion / June 23, 2014 Dr Marcus K Harmes, University of Southern Queensland | Early modern England, dated by historians as the period from c.1500 to 1700, permeates British television. The glittering and dramatic set pieces of Tudor, Elizabethan and Stuart history have long provided the dramatic substance of films and historical novels and, since the middle of the twentieth century, television drama as well. Totemic and highly recognisable aspects of the period, from processes including the Renaissance and Reformation, to individual figures such as Shakespeare and Elizabeth I, recur in shows as diverse as The Six Wives of Henry VIII to Blackadder II. The trend continues as seen in the popularity of works such as the Wolf Hall series by Hilary Mantel or HBO’s The Tudors. The early modern period has made occasional but telling appearances as a period visited by the Doctor and his companions in Doctor Who. More importantly, the period is now registering as one of increasing significance to the program, making exploration of early modernism within Doctor Who both timely and meaningful. The Doctor has visited early modern societies (always a European one) in serials across the last 50 years. From the ‘classic series’ these comprise ‘The Chase’ (1965), ‘The Massacre’ (1966), ‘The Smugglers’ (1966), ‘The Masque of Mandragora’ (1976), ‘City of Death’ (1979), ‘The Visitation’ (1982) and ‘Silver Nemesis’ (1988). From the ‘revived series’ they are ‘The Shakespeare Code’ (2007), ‘Vampires of Venice’ (2010), ‘Curse of the Black Spot’ (2011) and ‘The Day of the Doctor’ (2013). -

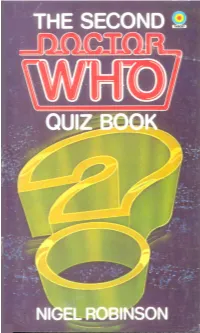

THE SECOND DOCTOR WHO QUIZ BOOK Also by Nigel Robinson

THE SECOND QUIZ BOOK NIGEL ROBINSON THE SECOND DOCTOR WHO QUIZ BOOK Also by Nigel Robinson The Doctor Who Quiz Book The Doctor Who Crossword Book THE SECOND DOCTOR WHO QUIZ BOOK Compiled by Nigel Robinson WWET A TARGET BOOK published by the Paperback Division of W. H. ALLEN & Co. PLC A Target Book Published in 1983 By the Paperback Division of W. H. Allen & Co. plc 44 Hill Street, London W1X 8LB Reprinted 1984 (twice) Copyright © Nigel Robinson 1983 ‘Doctor Who’ series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1983 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Anchor Brendon Limited, Tiptree, Essex ISBN 0 426 193504 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. CONTENTS The Questions General/1 11 The Adventures of the First Doctor/1 12 Adventures in History /1 13 The Adventures of the Second Doctor/1 14 The Daleks and the Thais/1 15 The Adventures of the Third Doctor /I 17 The Earth in Danger/1 18 Companions of the Doctor/1 19 The Adventures of the Fourth Doctor/1 20 The Key to Time/1 21 The Adventures of the Fifth Doctor/1 22 The Master/1 23 The Time Lords/1 24 The Adventures of the First Doctor/ 2 25 Adventures in History/ 2 26 The Adventures of the Second Doctor/2 27 Companions of the Doctor/2 28 The Cybermen/1 29 The Adventures of the -

TITLE CALL NUMBER for Film Information, Follow This Link: Www

For film information, follow this link: www.imdb.com TITLE FORMAT CALL NUMBER (500) days of Summer DVD PN 1997.2 .F58 2009 (Un)qualified: how God uses broken people to do big things AB CD BV 4598.2 .F87 2016 *Batteries not included DVD PN 1997 .B377 B377 1999 21 DVD PN 1997.2 .A149 A149 2008 300 DVD PN 1997.2 .E79 T4744 2007 1408 DVD PN 1995.9 .H6 F6878446 2007 2012 DVD PN 1997.2 .T835 2010 2 fast 2 furious DVD PN 1997 .F377 F377 2003 2 guns BLU-RAY PN 1997.2 .A12 2013 2 guns DVD PN 1997.2 .A12 2013 2nd chance AB CD PS 3566 .A822 A614 2002 3:10 to Yuma DVD PN 1997.2 .A138 A138 2007 3 comedy film favorites. Dodgeball DVD PN 1995.9 .C55 V38 2014 V.3 3 comedy film favorites. The internship DVD PN 1995.9 .C55 V38 2014 V.1 3 comedy film favorites. The watch DVD PN 1995.9 .C55 V38 2014 V.2 3 days to kill DVD PN 1997.2 .A15 2014 4 classic film favorites : Affair to remember DVD PN 1997 .A1 F68 2014 V.1 4 classic film favorites : Laura DVD PN 1997 .A1 F68 2014 V.2 4 classic film favorites : A letter to three wives DVD PN 1997 .A1 F68 2014 V.3 4 classic film favorites : The three faces of Eve DVD PN 1997 .A1 F68 2014 V.4 4 film favorites. Western collective DVD PN 1997 .Y68 2010 4 Film favorites: Girl's night collection: Chasing liberty DVD PN 1997 .E88 2010 V.4 4 Film favorites: Girl's night collection: Cinderella story DVD PN 1997 .E88 2010 V.1 4 Film favorites: Girl's night collection: Sisterhood of the traveling pants DVD PN 1997 .E88 2010 V.3 4 Film favorites: Girl's night collection: What a girl wants DVD PN 1997 .E88 2010 V.2 4 for Texas DVD PN 1995.9 .W4 F62 2005 The 5th wave DVD PN 1997.2 .A15 2016 The 6th day DVD PN 1997 .S597 S597 2001 9-1-1. -

Some Quotable Quotes for Statistics

Some Quotable Quotes for Statistics J. E. H. Shaw April 6, 2006 Abstract Well—mainly for statistics. This is a collection of over 2,000 quotations from the famous, (e.g., Hippocrates: ‘Declare the past, diagnose the present, foretell the future’), the infamous (e.g., Stalin: ‘One death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic’), and the cruelly neglected (modesty forbids. ). Such quotes help me to: • appeal to a higher authority (or simply to pass the buck), • liven up lecture notes (or any other equally bald and unconvincing narratives), • encourage lateral thinking (or indeed any thinking), and/or • be cute. I have been gathering these quotations for over twenty years, and am well aware that my personal collection needs rationalising and tidying! In particular, more detailed attributions with sources would be very welcome (but please no ‘I vaguely remember that the mth quote on page n was originally said by Winston Churchill/Benjamin Franklin/Groucho Marx/Dorothy Parker/Bertrand Russell/George Bernard Shaw/Mark Twain/Oscar Wilde/Steve Wright’.) If you use this collection substantially in any publication, then please give a reference to it, in the form: J.E.H. Shaw (2006). Some Quotable Quotes for Statistics. Downloadable from http://www.ewartshaw.co.uk/ Particular thanks to Peter Lee for tracking down ‘. damn quotes. ’ (see Courtney, Leonard Henry): http://www.york.ac.uk/depts/maths/histstat/courtney.htm. Other quote collections are given by Sahai (1979), Bibby (1983), Mackay (1977, 1991), and Gaither & Cavazos-Gaither (1996). Enjoy. Copyright c 1997–2006 by Ewart Shaw. If I have not seen as far as others, it is because giants were standing on my shoulders.