A Conversation with Dr. Clarence B. Jones Clayborne Carson Stanford University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BERKELEY SUMMER SESSIONS the Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr

Syllabus https://elearning.berkeley.edu/AngelUploads/Content/2013SUC... Printer Friendly Version BERKELEY SUMMER SESSIONS The Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr. (African American Studies 124, Summer Session 2013) about the course | materials | learning activities | grading | course policies | course outline About the Course Back to Top Course Description The life of Martin Luther King, Jr., provides a rare opportunity to understand the crucial issues of an era that shaped a good deal of contemporary America. As that era’s greatest leader, King’s life helps us both focus history and humanize it. As a profound thinker, as well as an activist, King epitomizes the interdependence of academic excellence and social responsibility. By examining the forces that shaped King’s life and his impact on society, we should gain some sense of history and historical possibility. By critically reviewing his political philosophy we should gain some appreciation of its depth and relevance for today. Recently, for example, protesters in Egypt were singing "We Shall Overcome." Each student will be expected to fully participate in the course including daily reading, watching the multimedia lecture presentations, engaging in interaction with the graduate student instructors and professor, posting short essays to a discussion board, interacting with peers in study sections, writing a critical book review of the Tyson book, taking four quizzes, and completing the mid-term and final examinations. Each quiz will count ten points. The mid-term and final examinations will count 20 points each and the critical book review will count 20 points. Extensions and incompletes will only be granted in rare circumstances. -

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr

THE PAPERS OF MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. Initiated, by The King Center in association with Stanford University After a request to negotiate with the Albany City Commission on 27July 1962 was denied, King, Ralph Abernathy, William G. Anderson, and seven others are escorted to jail by Police Chief Laurie Pritchett for disorderly conduct, congregating on the sidewalk, and disobeying a police officer. © Corbis. THE PAPERS OF MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. VOLUME VII To Save the Soul of America January 1961-August 1962 Senior Editor Clayborne Carson Volume Editor Tenisha Armstrong UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr., © 2014 by the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr. Introduction, editorial footnotes, and apparatus © 2014 by the Martin Luther King, Jr., Papers Project. © 2014 by The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address queries as appropriate to: Reproduction in print or recordings of the works of Martin Luther King, Jr.: the Estate of Martin Luther KingJr., in Atlanta, Georgia. All other queries: Rights Department, University of California Press, Oakland, California. -

Black Women As Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools During the 1950S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hostos Community College 2019 Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools during the 1950s Kristopher B. Burrell CUNY Hostos Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ho_pubs/93 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] £,\.PYoo~ ~ L ~oto' l'l CILOM ~t~ ~~:t '!Nll\O lit.ti t~ THESTRANGE CAREERS OfTHE JIMCROW NORTH Segregation and Struggle outside of the South EDITEDBY Brian Purnell ANOJeanne Theoharis, WITHKomozi Woodard CONTENTS '• ~I') Introduction. Histories of Racism and Resistance, Seen and Unseen: How and Why to Think about the Jim Crow North 1 Brian Purnelland Jeanne Theoharis 1. A Murder in Central Park: Racial Violence and the Crime NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS Wave in New York during the 1930s and 1940s ~ 43 New York www.nyupress.org Shannon King © 2019 by New York University 2. In the "Fabled Land of Make-Believe": Charlotta Bass and All rights reserved Jim Crow Los Angeles 67 References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or John S. Portlock changed since the manuscript was prepared. 3. Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in Names: Purnell, Brian, 1978- editor. -

Unwise and Untimely? (Publication of "Letter from a Birmingham Jail"), 1963

,, te!\1 ~~\\ ~ '"'l r'' ') • A Letter from Eight Alabama Clergymen ~ to Martin Luther J(ing Jr. and his reply to them on order and common sense, the law and ~.. · .. ,..., .. nonviolence • The following is the public statement directed to Martin My dear Fellow Clergymen, Luther King, Jr., by eight Alabama clergymen. While confined h ere in the Birmingham City Jail, I "We the ~ders igned clergymen are among those who, in January, 1ssued 'An Appeal for Law and Order and Com· came across your r ecent statement calling our present mon !)ense,' in dealing with racial problems in Alabama. activities "unwise and untimely." Seldom, if ever, do We expressed understanding that honest convictions in I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If racial matters could properly be pursued in the courts I sought to answer all of the criticisms that cross my but urged that decisions ot those courts should in the mean~ desk, my secretaries would he engaged in little else in time be peacefully obeyed. the course of the day, and I would have no time for "Since that time there had been some evidence of in constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of creased forbearance and a willingness to face facts. Re genuine goodwill and your criticisms are sincerely set sponsible citizens have undertaken to work on various forth, I would like to answer your statement in what problems which cause racial friction and unrest. In Bir I hope will he patient and reasonable terms. mingham, recent public events have given indication that we all have opportunity for a new constructive and real I think I should give the reason for my being in Bir· istic approach to racial problems. -

Extensions of Remarks E1775 HON. SAM GRAVES HON

December 10, 2014 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1775 On a personal note, Aubrey was a dear son to ever serve in the House of Representa- U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, U.S. Sen- friend and loyal supporter. I will always re- tives, the oldest person ever elected to a ator Lloyd Bentsen, T. Boone Pickens, H. member his kindness and his concern for peo- House term and the oldest House member Ross Perot, Red Adair, Bo Derek, Chuck Nor- ple who deserved a second chance. I will al- ever to a cast a vote. Mr. HALL is also the last ris, Ted Williams, Tom Hanks and The Ink ways remember him as a kind, gentle, loving, remaining Congressman who served our na- Spots. and brilliant human being who gave so much tion during World War II. He works well with both Republicans and to others. And for all of these accomplishments, I Democrats, but he ‘‘got religion,’’ in 2004, and Today, California’s 13th Congressional Dis- would like to thank and congratulate RALPH became a Republican. Never forgetting his trict salutes and honors an outstanding indi- one more time for his service to the country Democrat roots, he commented, ‘‘Being a vidual, Dr. Aubrey O’Neal Dent. His dedication and his leadership in the Texas Congressional Democrat was more fun.’’ and efforts have impacted so many lives Delegation. RALPH HALL always has a story and a new, throughout the state of California. I join all of Born in Fate, Texas on May 3, 1923, HALL but often used joke. -

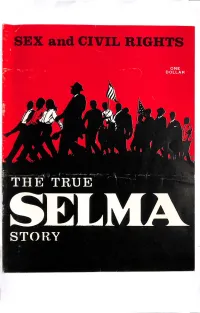

Martin Luther King and Communism Page 20 the Complete Files of a Communist Front Organization Were Taken in a Raid in New Orleans

Several hundred demonstrators were forced to stand on Dexter Ave1me in front of the State Capitol at Montgomery. On the night of March 10, 1965, these demonstrators, who knew that once they left the area they would not be able to return, urinated en masse in the street on the signal of James Forman, SNCC ExecJJtiVe Director. "All right," Forman shoute<)l, "Everyone stand up and relieve yourself." Almost everyone did. Some arrests were made of men who went to obscene extremes in expos ing themselves to local police officers. The True SELMA Story Albert C. (Buck) Persons has lived in Birmingham, Alabama for 15 years. As a stringer for LIFE and managing editor of a metropolitan weekly newspaper he covered the Birmingham demonstrations in 1963. On a special assignment for Con gressman William L. Dickinson of Ala bama he investigated the Selma-Mont gomery demonstrations in March, 1965. In 1961 Persons was one of a handful of pilots hired to support the invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. His story on this two years later led to the admission by President Kennedy that four Ameri can flyers had died in combat over the beaches of Southern Cuba in an effort to drive Fidel Castro from the armed Soviet garrison that had been set up 90 miles off the coast of the United States. After interviewing scores of people who were eye-witnesses to the Selma-Montgomery march, Mr. Persons has written the articles published here. In summation he says, "The greatest obstacle in the Negro's search for "freedom" is the Negro himself and the leaders he has chosen to follow. -

ANTHONY HILL, BLACK LIVES MATTER, and DSA by Adam Cardo

ANTHONY HILL, BLACK LIVES MATTER, AND DSA By Adam Cardo first became involved with DSA in the fall of 2014, as part of outside his apartment by DeKalb County Police officer Robert my larger political realignment brought on by the Black Lives Olson in March of 2015. Local activist groups who led the Matter movement. After spending the summer volunteering protest included Rise Up Georgia and #It’sBiggerThanYou, as for a moderate Democrat in Georgia, I began a semester at well as myself and several fellow Atlanta DSA members. We American University in Washington D.C., taking classes while also collected funds for the cause at our Socialist Dialogue. After interningI for another moderate Democrat. Fully enmeshed in an initial protest outside Hill’s neighborhood, activists focused mainstream “progressive” politics, I was all set to become a their efforts on securing an indictment of the accused officer neo-liberal Democratic Party apparatchik. However, two events with marches and rallies. The struggle culminated in a 3-day transpired to lead me camp-out outside the to the socialist light. DeKalb County The first was my courthouse during involvement with the the week of January Metro Washington 17th. The officer was D.C. DSA chapter, successfully indicted which I discovered on all six counts through a mutual against him. a c q u a i n t a n c e . The events The other crucial surrounding Anthony event was the non- Hill show the power indictment of the of Black Lives Matter police officers who in countering the murdered Eric Garner. -

Ahimsa Center- K-12 Teacher Institute Title of Lesson: the Courage Of

Ahimsa Center- K-12 Teacher Institute Title of Lesson: The Courage of Direct Action through Nonviolence in the Montgomery Bus Boycott Lesson By: Cara McCarthy Grade Level/ Subject Areas: Class Size: Time/Duration of Lesson: Fourth Grade 20-25 1 – 2 days Guiding Questions: • Is nonviolence courageous? Do you think nonviolence is more or less courageous than violence? • What was the effect of direct action (the disciplined nonviolent use of the body to protest injustice) on the Montgomery bus boycott? • Did Martin Luther King, Jr. create the Black Freedom Movement or did the movement create Martin Luther King, Jr. ? Use the example of Rosa Parks to explain your thinking. • Explain how the legacy of Rosa Parks bears witness to many of Martin Luther King Jr’s principles of nonviolence including education, personal commitment and direct action. Lesson Abstract: The students will explore the power of nonviolence inspired by Gandhi and disseminated by Dr. Dr. King in the Black Freedom Movement, which demanded equal rights for all humanity regardless of race or ethnicity. They will explore the power of direct action, disciplined nonviolence as practiced by a group of people (individually or en masse) in order to achieve a political/social justice goal. They will explore the impact of individual contributions to the dismantling of segregation through the practice of direct action as illustrated by the historical contribution of Rosa Parks. Her arrest propelled Dr. King and his belief in the philosophy of nonviolent direct action to the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement. Lesson Content: Dr. King, the leader of the Black Freedom Movement in the United States of America, advocated and practiced nonviolence in response to the aggressive and violent actions perpetrated by a strict system of segregation. -

A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1994 A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement Michelle Margaret Viera Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Viera, Michelle Margaret, "A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement" (1994). Master's Theses. 3834. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3834 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SUMMARY OF THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF FOUR KEY AFRICAN AMERICAN FEMALE FIGURES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by Michelle Margaret Viera A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1994 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My appreciation is extended to several special people; without their support this thesis could not have become a reality. First, I am most grateful to Dr. Henry Davis, chair of my thesis committee, for his encouragement and sus tained interest in my scholarship. Second, I would like to thank the other members of the committee, Dr. Benjamin Wilson and Dr. Bruce Haight, profes sors at Western Michigan University. I am deeply indebted to Alice Lamar, who spent tireless hours editing and re-typing to ensure this project was completed. -

MLK Resource Sheet

Created by Tonysha Taylor and Leah Grannum MLAC DEI 2021 Below you will find a complied list of resources, articles, events and more to honor the life and legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. The attempted coup at the Capitol on January 6th, 2021 was another reminder that we still have a lot of work to do to dismantle white supremacy. We hope you take this time to reflect, learn and remember Martin Luther King Jr. and his legacy- what he died for and what we continue to fight for. Resources and Virtual Events Teaching Black History and Culture: An Online Workshop for Educators. The workshop will be virtual (via Zoom) and combine a webinar, video and live streaming. Hosted by the Thomas D. Clark Foundation. Presented live from the Muhammad Ali Center. For more info and registration: https://nku.eventsair.com/ shcce/teaching/Site/Register Martin Luther King Jr. Day is a United States, holiday (third Monday in January) honoring the achievements of Martin Luther King, Jr. King’s birthday was finally approved as a federal holiday in 1983, and all 50 states A Call to Action: Then and Now: Dr. Martin Luther King, made it a state government holiday by 2000. Officially, King Jr. Celebration was born on January 15, 1929 in Atlanta. But the King holiday is marked every year on the third Monday in January. On January 18, 2021 at 3:45 p.m. EST the Madam Walker Legacy Center and Indiana University will Muhammad Ali Center MLK Day Celebration present "A Call to Action: Then and Now," a social justice virtual program with two of this nation's most prolific civil rights activists. -

2018 Discussion Guide

2018 Discussion Guide American Library Association Ethnic and Multicultural Information Exchange Round Table CORETTA SCOTT KING BOOK AWARDS COMMITTEE American Library Association Ethnic and Multicultural Information Exchange Round Table Coretta Scott King Book Awards Committee • www.ala.org/csk The Coretta Scott King Book Awards Discussion Guide was prepared by the 2018 Coretta Scott King Book Award Jury Chair Sam Bloom and members Kacie Armstrong, Jessica Anne Bratt, Lakeshia Darden, Sujin Huggins, Erica Marks, and Martha Parravano. The activities and discussion topics are developed to encompass state and school standards. These standards apply equally to students from all linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Students will demonstrate their proficiency, skills, and knowledge of subject matter in accordance with national and state stan- dards. Please refer to the US Department of Education website, www.ed.gov, for detailed information. The Coretta Scott King Book Awards seal was designed by artist Lev Mills in 1974. The symbolism of the seal reflects both Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s philosophy and the award’s ideals. The basic circle represents continuity in movement, revolving from one idea to another. Within the image is an African American child reading a book. The five main religious symbols below the image of the child represent nonsectarianism. The superimposed pyramid symbolizes both stength and Atlanta University, the award’s headquarters when the seal was designed. At the apex of the pyramid is a dove, symbolic of peace. The rays shine toward peace and brotherhood. The Coretta Scott King Book Awards seal image and award name are solely and exclusively owned by the American Library Association. -

Waveland, Mississippi, November 1964: Death of Sncc, Birth of Radicalism

WAVELAND, MISSISSIPPI, NOVEMBER 1964: DEATH OF SNCC, BIRTH OF RADICALISM University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire: History Department History 489: Research Seminar Professor Robert Gough Professor Selika Ducksworth – Lawton, Cooperating Professor Matthew Pronley University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire May 2008 Abstract: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced Snick) was a nonviolent direct action organization that participated in the civil rights movement in the 1960s. After the Freedom Summer, where hundreds of northern volunteers came to participate in voter registration drives among rural blacks, SNCC underwent internal upheaval. The upheaval was centered on the future direction of SNCC. Several staff meetings occurred in the fall of 1964, none more important than the staff retreat in Waveland, Mississippi, in November. Thirty-seven position papers were written before the retreat in order to reflect upon the question of future direction of the organization; however, along with answers about the future direction, these papers also outlined and foreshadowed future trends in radical thought. Most specifically, these trends include race relations within SNCC, which resulted in the emergence of black self-consciousness and an exodus of hundreds of white activists from SNCC. ii Table of Contents: Abstract ii Historiography 1 Introduction to Civil Rights and SNCC 5 Waveland Retreat 16 Position Papers – Racial Tensions 18 Time after Waveland – SNCC’s New Identity 26 Conclusion 29 Bibliography 32 iii Historiography Research can both answer questions and create them. Initially I discovered SNCC though Taylor Branch’s epic volumes on the Civil Right Movements in the 1960s. Further reading revealed the role of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced Snick) in the Civil Right Movement and opened the doors into an effective and controversial organization.