A Simple Proof of G¨Odel's Incompleteness Theorems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hotw May 2006-Save for Cd

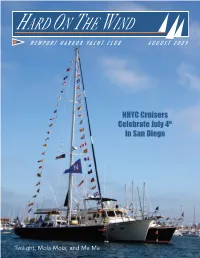

NHYC Cruisers Celebrate July 4th in San Diego Twilight, Mola Mola, and Me Me COMMODORE’S COLUMN for some and a record-setting pace for by Chris Welsh, Harry Patterson, Hubie others. This brings back fond memories Laugharn, Jamie Hardenbergh, and of sailing Transpac in 2001 on Alaska John Drayton. The Lynx crew included Eagle, the communications vessel, with Graham Brant-Zawadzki. Tom Corkett & SC Grant Baldwin. I had a great Tom Jr. were on Mirage. Doug Rastello opportunity to be “Baldy’s” and Piet van Os sailed on Pyewacket, communications computer operator and and our Vice Commodore Brad Avery his radio backup. This was a great trip and John Fuller were on Holua. and an opportunity to learn from the Meanwhile, our Non-Calm Program “Voice of Transpac”. has been going great guns, with 170 In the 1953 Transpac, my dad and kids sailing in the program. It is a others from NHYC sailed the Goodwill to pleasure to come down to the club in the late afternoon and see all these In days past, NHYC fired the Honolulu. The Goodwill was a classic old young sailors. I have heard parents and cannon for Evening Colors until too 160-foot schooner. In 1958, I sailed on grandparents talking with great pride many complained about the noise and the Goodwill to Catalina with the about helping junior members with their how it scared some people. After Douglas, Gardiner, and Crispin families. boats. Thanks to the Draytons, the Non- several requests, we have brought back Fellow member Ken Gardiner and I were Calm Committee, Zander, and his super Colors less the cannon, a great tradition just young kids at the time, but what an staff of instructors for making another followed by many yacht clubs such as adventure it was! There we were, sitting wonderful sailing summer. -

Evaluation of Impacts of the Development Capital Investment Intervention of the DFID India’S Private Sector Infrastructure Portfolio

Evaluation of impacts of the Development Capital Investment Intervention of the DFID India’s Private Sector Infrastructure Portfolio Draft Final Baseline Report Aug 2019 Submitted by: Author This evaluation report is prepared by the Evaluation Team of IPE Global Limited, India. The team members are: 1. Sanjay Sinha, Team Leader 2. Promila Bishnoi, Evaluation & VfM Expert 3. Gaurav Prateek, Research Manager 4. Manab Chakraborty, Institutional Expert 5. Achin Biyani, Finance Expert 6. Sheena Kapoor, Research Associate Contact Person Dr. Soumen Bagchi, Project Coordinator, [email protected] Copy Right Department for International Development, UK will have the copy right of the field data and information collected, and the evaluation report. Compliance with Ethics Principles IPE Global Limited maintains compliance with the global standards and policies, such as the OECD Standards for Development Evaluation, DFID’s Ethics Principles for Research and Evaluation (2011), and DFID’s zero tolerance stance on corruption and fraud. The corporate values and ethics are safeguarded through a set of policies and codes of conduct including anti-fraud and anti-corruption, conflict of interest, equity, diversity and quality assurance. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this report are those of the evaluation team and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the Department for International Development, UK. Evaluation of impacts of Development Capital Investment Intervention of DFID India’s Private Sector Infrastructure Portfolio Acronyms bn Billion -

65 – Automne/Hiver 2010

n° 65 – Automne/Hiver 2010 www.francelaser.org Revue trimestrielle de l'ASSOCIATION FRANCE LASER 9 port des Champs Élysées - 75008 PARIS 2 Le développement confirmé de la série 4.7 La lettre du Laser va permettre à de plus en plus de jeunes régatiers de découvrir les joies de la course n° 65 – Automne/Hiver en flotte sur le même bateau et par là, à 2010 assurer la pérennité de notre série pour Revue semestrielle de encore de nombreuses années supplémen- 200.000 : Voilà un nombre qui sonne bien ! taires. l'Association France Laser 200.000 c’est aussi un numéro que nous commencerons à voir sur nos lignes de Je limiterai à ces quelques lignes mes Ont participé à la rédaction de ce numé- départ en 2011. 200.000 , c’est le nombre commentaires sur la vie de la série, ce ro : Gilles GLUCK, Corinne JULLION, de Lasers construits dans le monde en 37 sujet, comme vous pourrez le voir en lisant Loïc GAUDOUEN, Pierre LEMAIRE, ans. cette revue, étant largement abordé dans le Christelle MARSAULT et Georges DU- compte rendu de l’assemblée générale RING et quelques masters, Corinne AN- Seul le Sunfish, cet exotique dériveur à 2010 de l’AFL. TOINE et les jeunes du stage franco- corne, confidentiel sous nos latitudes, mais allemand 2010. très populaire aux USA et aux Caraïbes, a Un petit cocorico quand même pour termi- fait mieux dans le monde. ner en soulignant qu’en réunissant 340 Parution du prochain numéro : concurrents (record battu) majoritairement Printemps 2011 Ce préambule pour vous confirmer que français, la 41° édition du grand prix de Date limite de remise des articles : malgré la crise qui ne nous a pas épargné, l’Armistice d’Hourtin a rassemblé près de 15 mars 2011 notre série ne se porte pas si mal. -

Norwegian Behind the King’S Choice: an Interview with Erik Poppe American Story on Page 10 Volume 128, #1 • November 3, 2017 Est

the Inside this issue: NORWEGIAN Behind The King’s Choice: an interview with Erik Poppe american story on page 10 Volume 128, #1 • November 3, 2017 Est. May 17, 1889 • Formerly Norwegian American Weekly, Western Viking & Nordisk Tidende $3 USD Edvard Munch: Color in Context A new exhibit in Washington, DC, uses theosophy to interpret the Norwegian artist’s use of color CHRISTINE FOSTER MELONI Washington, D.C. Was Norwegian artist Edvard Munch influenced by When visitors enter the small gallery, they may pick WHAT’S INSIDE? the philosophical and pseudo-scientific movements of up a laminated card with the color chart created by the Hvor vakkert bladene eldes. « Nyheter / News 2-3 his time? theosophists in 1901. The chart shows the colors corre Så fulle av lys og farge er deres He definitely came into contact with spiritualists sponding to 25 different thought forms (e.g., dark green siste dager. » Business 4-5 when he was young. His childhood vicar was the Rev. represents religious feeling, tinged with fear). They can – John Burroughs Opinion 6-7 E. F. B. Horn, a well-known spiritualist. While living then use this chart to determine the emotions Munch Sports 8-9 as a young artist in Oslo, he became familiar with the was trying to convey. Arts & Entertainment 10-11 Scientific Public Library of the traveling medium Hen Let’s look at two of these prints and consider the drick Storjohann. possible interpretations according to the color chart. Taste of Norway 12-13 The current exhibit at the National Gallery in Norway near you 14-15 Washington, D.C., sets out to explain how Munch ap Girl’s Head against the Shore Travel 16-17 plied theosophic ideas to his choice and combination of In this color woodcut we see a woman with black Norwegian Heritage 18-19 colors. -

27Th International Midwinter Regatta at Clearwater -Pasted Phmq Oiaj

APRIL 1964 Publicity Program for SCIRA Vol. XII No. 11 27th International Midwinter Regatta at Clearwater -pasted phmQ oiaj This easy to fix nless steel bailer will keep your Snipe free of water small bailer even in moderate price $ 6.00 breezes. ELVSTROM SAILS - RUNGSTED - DENMARK nuw)>n»>iii-.M'i'i^iiiui)iii»iu)im»mimuH»iiiiwmii)i BUILT ARE YOU IN THE WINNING CIRCLE? Varalyay SNIPES A "Sailand" Snipe will help get you there! FOR PERFORMANCE QUALITY BEAUTY * SAIL OUR ALL FIBERGLAS SNIPE Featuring OUR NEW MOLDED FOAM CORE DECK ORDER NOW Complete or Semi-Finished LEON F. IRISH CO. 4300 Hoggerty Rd. Walled Lake, Mich. VARALYAY BOAT WORKS WRITE FOR FULL INFORMATION AND PRICES 1868 W 166 STREET GARDENA. CALIFORNIA mm- 1n..„„1-.„»i.,»imiv<m»iiifnvim»i»iinm-nwi The Tillman Hiking Machine CAPT.DICK, 1959 NATIONAL CHAMPION, REVEALS ONE no matter how you look at her, she's a OF HIS SECRETS. Last summer I developed an apparatus to condition myself for Finn racing. It simulates the hiking and sheet tending normally encountered in a Finn and should be equally as useful for a Snipe. Perhaps a few hearty and healthy Snipers, grown soft over the winter, could use this idea in preparing for some TT03HMIJ of the several midwinter and spring regattas. Basically, the machine consists of a bench to sit on, straps to hike from, and a sheet to pull on. Figure 1 gives the side and top dimensions of the hiking machine and Table 2 is the complete list of materials required to build it. -

“Pat” Murphy Date of Interview: October 31, 2010 Interviewer: Willis Schueler Date of Transcription: November 10, 2010

SARASOTA COUNTY WATER ATLAS ORAL HISTORY PROJECT NEW COLLEGE OF FLORIDA—FALL 2010 Interview with: Patrick “Pat” Murphy Date of Interview: October 31, 2010 Interviewer: Willis Schueler Date of Transcription: November 10, 2010 Schueler: So, could you—just to start—state your name? Murphy: Name is Patrick Murphy. Schueler: And, could you tell me a bit about your background, where you‟re from? Murphy: Born in Iowa, came down here first time in „48. I actually, pardon me, came down here for the first time in „43. I was very young. Then, we moved to California for two years, Kenosha, Missouri for two years, and back here in „48. Been here most of the time since then, except I went to Florida State in „54 for a Bachelor‟s degrees, then Tulane for a Master‟s degrees in the early „60s. Been back here since „69. Schueler: When you first moved to Sarasota, you were about starting high school, that sort of age? Murphy: Oh, I was in 2nd grade in elementary school at Southside. Schueler: My math must‟ve been bad. When you first moved here did you spend a lot of time on the water? What was your relationship to the water? Murphy: Oh no, this town had about 10 to 12 thousand people and it was during the war. When we came back it was still small in the late „40s, early „50s. It would grow a little bit in the „50s, spurts. And then, it really jumped later on. Schueler: So, but for you personally, when you did first get really involved with the water? Sailing, or any other activity? Murphy: That was in actually „48 or „49. -

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Tuesday, February 12, 2013 12:12:12 PM School: Woodland Middle School

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Tuesday, February 12, 2013 12:12:12 PM School: Woodland Middle School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 144408 EN 13 Curses Harrison, Michelle MG 5.3 16.0 107,383 F 136675 EN 13 Treasures Harrison, Michelle MG 5.3 11.0 73,953 F 8251 EN 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda Lee MG 5.2 1.0 5,229 NF 9801 EN 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne MG 6.4 1.0 6,130 NF 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George UG 8.9 17.0 88,942 F 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Verne, Jules MG 10.0 28.0 138,138 F (Unabridged) 11592 EN 2095 Scieszka, Jon MG 3.8 1.0 10,043 F 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague MG 3.3 1.0 10,339 F 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa MG 5.6 7.0 43,360 F 1302 EN 3 NBs of Julian Drew, The Deem*, James M. U 3.6 5.0 38,042 F 128675 EN 3 Willows: The Sisterhood Grows Brashares, Ann MG 4.5 9.0 63,547 F 8252 EN 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. MG 4.2 1.0 5,130 NF 901 EN Abduction Kehret*, Peg U 4.7 6.0 39,470 F 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette UG 6.0 8.0 50,015 F 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William MG 5.9 3.0 17,610 F 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth UG 6.6 16.0 99,206 F 14931 EN Abominable Snowman of Stine, R.L. -

Seattle's First NOOD Was a Resounding Success

June, 2008 Seattle’s First NOOD was a resounding success By Steve Travis and won the regatta on a tie breaker NOOD Regatta Co-Chair after throwing out an 8th with Nicoli Lenti throwing out a 6th. Close to 800 sailors gathered for the first of which will become an annual event Stephen also claimed “boat of the re- that was held in Seattle May 16 to 18 on gatta” and thus a trip to the Caribbean the waters of Puget Sound for the “Sperry in November to compete against other Top Sider NOOD regatta”. NOOD regatta winners courtesy of Sunsail. It was great to see the vener- The event was organized by Sailing J-29s on the wind, Photo Neil Rabinowitz able 6 meters out again, with the top World and co-hosted by CYC and SYC two boats separated by only 3 points and drew 231 boast in 24 fleets, ranging recent memory. Some of the older sailors after ten races with the winner being from the ultra modern single handed were trying to remember the last time we Andy Parker in Finnegan. The J105 musto skiffs, to F-18 Catamarans, to the had that many racing and in the end, since no fleet was controlled by Michael Schiltz classic 6 meters. In between were large conclusion could be reached, it was decided with five 1sts in six races. The 11 boat fleets of J-24’s, Melges 24’s, Thunder- that it must have been in the last century San Juan 21 class was won by local ( birds, Lasers, 505’s, Melges 24’s, San some time!!!! We were fortunate to have Federal Way) Chris Popich in a fairly Juan 21’s and Santana 20’s. -

Free Snowbird Show Tues & Wed Jan 28 & 29 Rp Funding Center • 9:00 Am to 4:30 Pm 701 W

POLK NEWS-SUN VOL. 90 NO. 4 Wednesday, January 22, 2020 www.polknewssun.com $1.00 The Lake Wales News INSIDE THIS EDITION Participation Program seeing results implications A matching grant program discussed at aimed at attracting restaurants to Lake Wales PRWC meeting is having success. PG 3 By CHARLES A. BAKER III Staff Writer Orlando Health POLK COUNTY – At a Polk comes to Polk Regional Water Cooperative meeting The healthcare provider Jan. 15, Polk County Commissioner has purchased land near George Lindsey and PRWC lawyer Ed Lakeland, marking its de la Parte repeated what Frostproof Mayor Martin Sullivan described as entrance into the Polk an “old threat.” County market. Lindsey and de la Porte said that any PG 12 Polk County municipality that does not want to participate in the PRWC plan to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on two Lower Floridan Aquifer (LFA) wellfields and the associated PHOTO BY CHARLES A. BAKER III desalination treatment plants may not Participants in the Alafia River Rendezvous don traditional attire from the mid-1800s and set up have any access to additional water to camp as early as late-December. The campsite is open to the public this weekend. fuel future growth. The only Polk County municipality not to opt in as a member of the PRWC History comes alive at Alafia River in 2017 was the City of Frostproof. "That is the same old threat we heard Rendezvous a few years ago,” Sullivan said. “It was a veiled threat then, but foreshadowed exactly what has become the actual By CHARLES A. -

Notices of the American Mathematical Society ABCD Springer.Com

ISSN 0002-9920 Notices of the American Mathematical Society ABCD springer.com Visit Springer at the of the American Mathematical Society 2010 Joint Mathematics December 2009 Volume 56, Number 11 Remembering John Stallings Meeting! page 1410 The Quest for Universal Spaces in Dimension Theory page 1418 A Trio of Institutes page 1426 7 Stop by the Springer booths and browse over 200 print books and over 1,000 ebooks! Our new touch-screen technology lets you browse titles with a single touch. It not only lets you view an entire book online, it also lets you order it as well. It’s as easy as 1-2-3. Volume 56, Number 11, Pages 1401–1520, December 2009 7 Sign up for 6 weeks free trial access to any of our over 100 journals, and enter to win a Kindle! 7 Find out about our new, revolutionary LaTeX product. Curious? Stop by to find out more. 2010 JMM 014494x Adrien-Marie Legendre and Joseph Fourier (see page 1455) Trim: 8.25" x 10.75" 120 pages on 40 lb Velocity • Spine: 1/8" • Print Cover on 9pt Carolina ,!4%8 ,!4%8 ,!4%8 AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY For the Avid Reader 1001 Problems in Mathematics under the Classical Number Theory Microscope Jean-Marie De Koninck, Université Notes on Cognitive Aspects of Laval, Quebec, QC, Canada, and Mathematical Practice Armel Mercier, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi, QC, Canada Alexandre V. Borovik, University of Manchester, United Kingdom 2007; 336 pages; Hardcover; ISBN: 978-0- 2010; approximately 331 pages; Hardcover; ISBN: 8218-4224-9; List US$49; AMS members 978-0-8218-4761-9; List US$59; AMS members US$47; Order US$39; Order code PINT code MBK/71 Bourbaki Making TEXTBOOK A Secret Society of Mathematics Mathematicians Come to Life Maurice Mashaal, Pour la Science, Paris, France A Guide for Teachers and Students 2006; 168 pages; Softcover; ISBN: 978-0- O. -

The Sailboat –Then Decided to Race Them

Man created the slowest form of transportation – the sailboat –then decided to race them Objectives • Racing is not scary. • Cover the basics. • Get safely around the course. – Not a detailed study of the racing rules. • You do not have to win to have fun Types of Racing Boats • One-design – boats of the same design compete against each other e.g.,Flying Scots, Scows, Optimist Prams and many others. • Handicap – to allow boats of different design to compete against each other. Most often used for local cruising type boats. Handicap Systems • Not like golf, handicap boat, not skipper. – Assumes boat driven to max potential • We use Performance Handicap Rating Fleet, • All systems are imperfect. PHRF Performance Handicap Racing Fleet • Numerical rating assigned based on formula with empirical modifications. • Boats with lower rating are expected to be faster than boats with higher ratings. – waterline length - theoretical hull speed – Displacement • A Catalina 36 rated 219 will sail faster than a Catalina 22 rated 305 • Mostly uses a system where 1 point difference in rating = 1 second per nautical mile of race. How to Get a Rating • West Florida PHRF is the organizing body on Florida’s west coast. – http://wfphrf.org • Can be done on-line. • Cost $50.00. • Just fill out form. – We can help you if you have questions. • Get rating for accuracy, else we use our best guess. – Some regattas require a rating certificate, otherwise sail in a “fun fleet” The Fleet Spreads Out For a 1 NM First Leg Seconds Behind Boat Rating At First Mark Olson 30 119 -------------- J-24 171 52 Holder 20 209 90 S2 6.9 244 125 Precision 23 260 141 Pearson Ensign 278 159 At The Finish For a 6 NM Race Time Behind Boat Rating At Finish Olson 30 119 -------------- J-24 171 5 minutes, 12 seconds Holder 20 209 9 minutes S2 6.9 244 12 minutes, 30 seconds Precision 23 260 14 minutes, 6 seconds Pearson Ensign 297 15 minutes, 54 seconds Classes • Typical cruiser: generally over 30 feet l.o.a. -

2013 Seattle Area Sailboat Racing Calendar This Calendar List Sailboat Races in the Puget Sound Area

2013 Seattle Area Sailboat Racing Calendar This calendar list sailboat races in the Puget Sound area. Races are subject to change. Please check with the hosting Yacht club for additional information and sailing instuctions (SI).The Seattle Area Racing Calendar is also on Google Calendars: http://snipurl.com/seattle_sarc The Google calendar is updated periodically. JANUARY 11 SYC Vashon Island - TI 2 28 & 29 CYCT/TYC OD&PHRF Srs 5 TT Duwamish Head -SSS 2 11 WSCYC Novice Regatta 29 CYCE Halloween 3 12 SB Snowbird 17-19 SYC & CYC NOOD OCTOBER 13 NWGoosebump Series 25-26 RV Swiftsure 5 CYCE Foulweather Bluff 19 CYCT Quartermaster Hbr 25-26 WS Kitsap Regatta 5 TT Fall Series 20 NW Goosebump (Lk Union) 25-26 CYCT Cutts Island 5&6 CYC Small boat PSSC 26 ST Iceberg JUNE 12 & 13 CYC Large boat PSSC 26 TT Blake Island 1 SYC Blake Island - TI 3 12 CYCT Memorial Single Hand 27 NW Goosebump (Lk Union) 1 & 2 PM Fal Joslin 13 CYCE Halloween FEBRUARY 7-9 AYC Windemere Cup 19 CYCT Command Point 3 NW Goosebump (Lk Union) 8 Leukemia Cup (SYC) 19 ST Fall Regatta 9 SB Snowbird 8-22 Van Isle 360 19 ST Race Your House 9 OYC Toliva Shoal -SSS 3 14 &15 CYCT Fun on Fridays 1 25-27 SYC Grand Prix 9 & 10 SL Fridgit Digit 15 ST/PM Three Buoy Fiasco 26 CYCT Pt. Defiance 10 NW Goosebump (Lk Union) 22 TYC CYCT Summer Vashon 27 CYCE Halloween 10 CYCE Frostbite 22-23 CYC OD Late Days Regatta NOVEMBER 16 CYCT Gig Harbor 22 &23 CYCE Mad Dash 2 CYCT Brown's Point 17 NW Goosebump (Lk Union) 28 & 29 CYCT Fun on Fridays 2 2 TT Winter Srs 23 WS Dupue Memorial 29 WS Brownsville Race 2 DD Rum Run (tent) 23 TT Manzanita Buoy 29 CYC Jack and Jill 9 & 10 OI Round the County 24 CYCE Frostbite JULY 9 GH La Mans - 50th Anniversary MARCH 13-14 DWI (Dinghy's Whidbey Isl.) 16 TT Winter Srs 2 CYC Blakely Rock -CSS 1 14-19 Whidbey Is Race Week 16 SB Snowbird 9 CYC Scatchet Head - CSS 2 27 SYC Jack & Jill 16 WSCYC Fowl Weather 10 CYCE Frostbite AUGUST 23 & 24 CYC Turkey Bowl 16 GH Islands Race - SSS 4 3-4 ST Down the Sound DECEMBER 16 SB Snowbird 10 HR Double Dammed 7 TYC Winter Vashon SSS 1 23 CYC Three Tree Pt.