The Wastelands in Assam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Abikal Borah 2015

Copyright By Abikal Borah 2015 The Report committee for Abikal Borah certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) Supervisor: ________________________________________ Mark Metzler ________________________________________ James M. Vaughn A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M. Phil Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2015 A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M.A. University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Mark Metzler Abstract: This essay considers the history of two commodities, tea in Georgian England and opium in imperial China, with the objective of explaining the connected histories in the Eurasian landmass. It suggests that an exploration of connected histories in the Eurasian landmass can adequately explain the process of integration of southeastern sub-Himalayan region into the global capitalist economy. In doing so, it also brings the historiography of so called “South Asia” and “East Asia” into a dialogue and opens a way to interrogate the narrow historiographical visions produced from area studies lenses. Furthermore, the essay revisits a debate in South Asian historiography that was primarily intended to reject Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system theory. While explaining the historical differences of southeastern sub-Himalayan region with peninsular India, Bengal, and northern India, this essay problematizes the South Asianists’ critiques of Wallerstein’s conceptual model. -

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

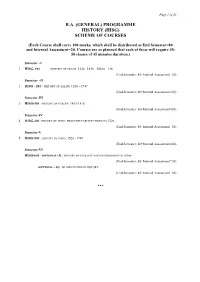

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

Women Education in Colonial Assam As Reflected in Contemporary Archival and Literary Records Chiranjib Dahal

SSRG International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Volume 8 Issue 3, 80-86, May-June, 2021 ISSN: 2394 – 2703 /doi:10.14445/23942703/IJHSS-V8I3P112 © 2021 Seventh Sense Research Group® Women Education in Colonial Assam as Reflected In Contemporary Archival And Literary Records Chiranjib Dahal Assistant Professor, Department of History, J.D.S.G. College, Bokakhat Dist.: Golaghat, State: Assam, Country: India 785612 Received Date: 15 May 2021 Revised Date: 21 June 2021 Accepted Date: 03 July 2021 Abstract - The present paper makes an attempt to trace the which can be inferred from literacy rate from 0.2 % in genesis and development of women’s education in colonial 1882 to 6% only in 1947(Kochhar,2009:225). It reveals Assam and its contribution to their changing status and that for centuries higher education for women has been aspirations. The contribution of the native elites in the neglected and the report University Education Commission process of the development of women education; and 1948 exposed that they were against women education. In social perception towards women education as reflected in their recommendation they wrote “women’s present the contemporary periodicals are some other areas of this education is entirely irrelevant to the life they have to lead. study. Educational development in Assam during the It is not only a waste but often a definite disability” colonial rule has generally been viewed by educational (University Education Commission Report, Government of historians to be the work of British rulers who introduced India, 1948-49). Educational development in Assam a system of education with the hidden agenda of initiating during the colonial rule has generally been viewed by a process of socialization. -

Event, Memory and Lore: Anecdotal History of Partition in Assam

ISSN. 0972 - 8406 61 The NEHU Journal, Vol XII, No. 2, July - December 2014, pp. 61-76 Event, Memory and Lore: Anecdotal History of Partition in Assam BINAYAK DUTTA * Abstract Political history of Partition of India in 1947 is well-documented by historians. However, the grass root politics and and the ‘victim- hood’ of a number of communities affected by the Partition are still not fully explored. The scholarly moves to write alternative History based on individual memory and family experience, aided by the technological revolution have opened up multiple narratives of the partition of Assam and its aftermath. Here in northeast India the Partition is not just a History, but a lived story, which registers its presence in contemporary politics through songs, poems, rhymes and anecdotes related to transfer of power in Assam. These have remained hidden from mainstream partition scholarship. This paper seeks to attempt an anecdotal history of the partition in Assam and the Sylhet Referendum, which was a part of this Partition process . Keywords : sylhet, partition, referendum, muslim league, congress. Introduction HVSLWHWKHSDVVDJHRIPRUHWKDQVL[W\¿YH\HDUVVLQFHWKHSDUWLWLRQ of India, the politics that Partition generated continues to be Dalive in Assam even today. Although the partition continues to be relevant to Assam to this day, it remains a marginally researched area within India’s Partition historiography. In recent years there have been some attempts to engage with it 1, but the study of the Sylhet Referendum, the event around which partition in Assam was constructed, has primarily been treated from the perspective of political history and refugee studies. 2 ,W LV WLPH +LVWRU\ ZULWLQJ PRYHG EH\RQG WKH FRQ¿QHV RI political history. -

Power Structure, Discipline, and Labour in Assam Tea Plantations Under Colonial Rule

IRSH 51 (2006), Supplement, pp. 143–172 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859006002641 # 2006 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Power Structure, Discipline, and Labour in Assam Tea Plantations under Colonial Rule Rana P. Behal The tea industry, from the 1840s onwards the earliest commercial enterprise established by private British capital in the Assam Valley, had been the major employer of wage labour there during colonial rule. It grew spectacularly during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when tea production increased from 6,000,000 lb in 1872 to 75,000,000 lb in 1900 and the area under tea cultivation expanded from 27,000 acres to 204,000 acres.1 Employment of labour in the Assam Valley tea plantations increased from 107,847 in 1885 to 247,760 in 1900,2 and the industry continued to grow during the first half of the twentieth century. At the end of colonial rule the Assam Valley tea plantations employed nearly half a million labourers out of a labour population of more than three-quarters of a million, and more than 300,000 acres were under tea cultivation out of a total area of a million acres controlled by the tea companies.3 This impressive expansion and the growth of the Assam Valley tea industry took place within the monopolistic control of British capital in Assam. An analysis of the list of companies shows that in 1942 84 per cent of tea estates with 89 per cent of the acreage in the Assam Valley were controlled by the European managing agency houses.4 Throughout India, thirteen leading agency houses of Calcutta controlled over 75 per cent of total tea production in 1939.5 Elsewhere I have shown that the tea companies reaped profits over a long time despite fluctuating international prices and slumps.6 One of the most notable features of the Assam Valley tea plantations was that, unlike in the cases of most of the other major industries such as jute, textiles, and mining in British India, it never suffered from a complete 1. -

Imperialism, Geology and Petroleum: History of Oil in Colonial Assam

SPECIAL ARTICLE Imperialism, Geology and Petroleum: History of Oil in Colonial Assam Arupjyoti Saikia In the last quarter of the 19th century, Assam’s oilfields Assam has not escaped the fate of the newly opened regions of having its mineral resources spoken of in the most extravagant and unfounded became part of the larger global petroleum economy manner with the exception of coal. and thus played a key role in the British imperial – H B Medlicott, Geological Survey of India economy. After decolonisation, the oilfields not only he discovery of petroleum in British North East India (NE) turned out to be the subject of intense competition in a began with the onset of amateur geological exploration of regional economy, they also came to be identified with Tthe region since the 1820s. Like tea plantations, explora tion of petroleum also attracted international capital. Since the the rights of the community, threatening the federal last quarter of the 19th century, with the arrival of global techno structure and India’s development paradigm. This paper logy, the region’s petroleum fields became part of a larger global is an attempt to locate the history of Assam’s oil in the petroleum economy, and, gradually, commercial exploration of large imperial, global and national political economy. petroleum became a reality. It was a time when geologists had not yet succeeded in shaping an understanding of the science of It re-examines the science and polity of petroleum oil and its commercial possibilities. Over the next century, the exploration in colonial Assam. Assam oilfields played a key role in the British imperial economy. -

Empire's Garden: Assam and the Making of India

A book in the series Radical Perspectives a radical history review book series Series editors: Daniel J. Walkowitz, New York University Barbara Weinstein, New York University History, as radical historians have long observed, cannot be severed from authorial subjectivity, indeed from politics. Political concerns animate the questions we ask, the subjects on which we write. For over thirty years the Radical History Review has led in nurturing and advancing politically engaged historical research. Radical Perspec- tives seeks to further the journal’s mission: any author wishing to be in the series makes a self-conscious decision to associate her or his work with a radical perspective. To be sure, many of us are currently struggling with the issue of what it means to be a radical historian in the early twenty-first century, and this series is intended to provide some signposts for what we would judge to be radical history. It will o√er innovative ways of telling stories from multiple perspectives; comparative, transnational, and global histories that transcend con- ventional boundaries of region and nation; works that elaborate on the implications of the postcolonial move to ‘‘provincialize Eu- rope’’; studies of the public in and of the past, including those that consider the commodification of the past; histories that explore the intersection of identities such as gender, race, class and sexuality with an eye to their political implications and complications. Above all, this book series seeks to create an important intellectual space and discursive community to explore the very issue of what con- stitutes radical history. Within this context, some of the books pub- lished in the series may privilege alternative and oppositional politi- cal cultures, but all will be concerned with the way power is con- stituted, contested, used, and abused. -

Historiography of the Formation of Assamese Identity: a Review

Peace and Democracy in South Asia, Volume 2, Numbers 1 & 2, 2006. HISTORIOGRAPHY OF THE FORMATION OF ASSAMESE IDENTITY: A REVIEW MADHUMITA SENGUPTA A thematic review of Planter Raj to Swaraj: Freedom Struggle and Electoral Politics in Assam, 1826-1947 by A. Guha; Assam: A Burning Question by H. Gohain; Roots of Ethnic Conflict: Nationality Questions in North East India by S. Nag; Social Tensions in Assam Middle Class Politics by A.K. Baruah; and India Against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Identity by S. Baruah. Introduction Assam, tucked away in the Northeast corner of India is a state that has been locked for the last few years in a bloody struggle between ‘insurgents’ and the state as the architect of counter-insurgency operations. This may not come as a surprise, for Assam is not the only insurgency-ridden state in this country. But what makes Assam special and at the same time vulnerable is its geographical location in a region that is surrounded by international borders on three sides. It makes sense therefore to trace the roots of this ‘ethnic’ turmoil by taking a look at how an Assamese identity came to be imagined here in the nineteenth century. The history of Assamese identity is a rather interesting one for the very reason that it is at once a story of the formation and transformation of the community. It has been remarked by one author (Misra 2001) that what has been happening in Assam over the past few decades in the matter of the widening of the parameters of the Assamese nationality as a result of swift demographic change, may be said to be unique not only in relation to the other Peace and Democracy in South Asia, Volume 2, Numbers 1 & 2, 2006. -

Identity and Violence in India's North East: Towards a New Paradigm

Identity and Violence In India’s North East Towards a New Paradigm Sanjib Goswami Institute for Social Research Swinburne University of Technology Australia Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Ethics Clearance for this SUHREC Project 2013/111 is enclosed Abstract This thesis focuses on contemporary ethnic and social conflict in India’s North East. It concentrates on the consequences of indirect rule colonialism and emphasises the ways in which colonial constructions of ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ identity still inform social and ethnic strife. This thesis’ first part focuses on history and historiography and outlines the ways in which indirect rule colonialism was implemented in colonial Assam after a shift away from an emphasis on Britain’s ‘civilizing mission’ targeting indigenous elites. A homogenising project was then replaced by one focusing on the management of colonial populations that were perceived as inherently distinct from each other. Indirect rule drew the boundaries separating different colonised constituencies. These boundaries proved resilient and this thesis outlines the ways in which indirect rule was later incorporated into the constitution and political practice of postcolonial India. Eventually, the governmental paradigm associated with indirect rule gave rise to a differentiated citizenship, a dual administration, and a triangular system of social relations comprising ‘indigenous’ groups, non-indigenous Assamese, and ‘migrants’. Using settler colonial studies as an interpretative paradigm, and a number of semi-structured interviews with community spokespersons, this thesis’ second part focuses on the ways in which different constituencies in India’s North East perceive ethnic identity, ongoing violence, ‘homeland’, and construct different narratives pertaining to social and ethnic conflict. -

SUB-REGIONAL NATIONALISM in ASSAM PRINT MEDIA by Joydeep

Commentary-2 Global Media Journal – Indian Edition Sponsored by the University of Calcutta/www.caluniv.ac.in ISSN 2249 – 5835 Summer& Winter Joint Issue/June- December 2015/Vol. 6/No. 1& 2 SUB-REGIONAL NATIONALISM IN ASSAM PRINT MEDIA by Joydeep Biswas Associate Professor Cachar College, Silchar, Assam University email: [email protected] Abstract – The genesis and growth of the nearly 170-year-old Assam print media is intricately linked to, and shaped by the sub-regional Assamese nationalism. Since the time when the first Assamese news periodical, Orunodai, was brought out under the aegis of the American Baptist Missionaries from Sibsagar or much later down the line when the first daily, Dainik Batori, began to be churned out from the outskirts of Jorhat in 1935 till the fag end of the last century when in 1995 the highest circulated Assamese daily, Asomiya Pratidin, was first published, Assam print media journalism has always rallied around Assamese nationalism. The birth of the Assam Tribune in 1939 and the Sentinel in 1983-both English dailies-and their subsequent rise to prominence also could not alter the trend. While such nationalist journalism at the formative stage of construction of Assamese identity is understandable, not unheard of also in other provinces of colonial India, and justified as well, continuation of the same strand even after 1947 and, in fact, till into the present time, has worked against some key principles of journalism like objectivity, accuracy, fairness and impartiality. Evidence of such journalistic aberration in Assam print media is particularly visible vis-à-vis the issue of rights of the Partition victim Bengali settlers in Assam. -

People of the Margins Philippe Ramirez

People of the Margins Philippe Ramirez To cite this version: Philippe Ramirez. People of the Margins. Spectrum, 2014, 978-81-8344-063-9. hal-01446144 HAL Id: hal-01446144 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01446144 Submitted on 25 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. People of the Margins People of the Margins Across Ethnic Boundaries in North-East India Philippe Ramirez SPECTRUM PUBLICATIONS GUWAHATI : DELHI In association with CNRS, France SPECTRUM PUBLICATIONS • Hem Barua Road, Pan Bazar, GUWAHATI-781001, Assam, India. Fax/Tel +91 361 2638434 Email [email protected] • 298-B Tagore Park Extn., Model Town-1, DELHI-110009, India. Tel +91 9435048891 Email [email protected] Website: www.spectrumpublications.in First published in 2014 © Author Published by arrangement with the author for worldwide sale. Unless otherwise stated, all photographs and maps are by the author. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted/used in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. -

A Study on the Cultivation of Jute in Colonial Assam and the Immigration from East-Bengal

International Journal of Grid and Distributed Computing Vol. 13, No. 2, (2020), pp. 1716-1729 A study on the cultivation of jute in Colonial Assam And the Immigration from East-Bengal. KRISHNA KALITA Research Scholar Department of History Dibrugarh University Abstract Jute was one of the important and profitable crop in colonial Assam. Due to the lack of historical evidences it is difficult to ascertain the history of the jute cultivation in Assam but, jute cultivation had taken place enormously only in the colonial Assam by the East-Bengali immigrants. The colonial government encouraged immigration from East Bengal and reclamation of waste land to cultivate jute as the crop was highly labour intensive and lack of knowledge of the indigenous people about the cultivation of jute. So in this article, the author will deal with a study on the cultivation of jute in colonial Assam and the immigration from East-Bengal. Key-words – Colonial Assam, Jute , East- Bengali immigration, Brahmaputra valley. Introduction The plains of the Brahmaputra valley of Assam provide a fertile ground for the cultivation of various crops and various types fibre crops were being cultivated in Assam so far. However, certain crop like jute was not considered as an important crop to be cultivated in Assam even in the early part of the 20th century. It is difficult to ascertain the history jute cultivation of Assam due to the lack of historical evidences. But, historical evidences suggest that the jute cultivation in Assam had taken place enormously only in the colonial period by the east Bengal immigrants.