Remembering Sylhet: a Forgotten Story of India's 1947 Partition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Abikal Borah 2015

Copyright By Abikal Borah 2015 The Report committee for Abikal Borah certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) Supervisor: ________________________________________ Mark Metzler ________________________________________ James M. Vaughn A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M. Phil Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2015 A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M.A. University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Mark Metzler Abstract: This essay considers the history of two commodities, tea in Georgian England and opium in imperial China, with the objective of explaining the connected histories in the Eurasian landmass. It suggests that an exploration of connected histories in the Eurasian landmass can adequately explain the process of integration of southeastern sub-Himalayan region into the global capitalist economy. In doing so, it also brings the historiography of so called “South Asia” and “East Asia” into a dialogue and opens a way to interrogate the narrow historiographical visions produced from area studies lenses. Furthermore, the essay revisits a debate in South Asian historiography that was primarily intended to reject Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system theory. While explaining the historical differences of southeastern sub-Himalayan region with peninsular India, Bengal, and northern India, this essay problematizes the South Asianists’ critiques of Wallerstein’s conceptual model. -

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Political Phenomena in Barak-Surma Valley During Medieval Period Dr

প্রতিধ্বতি the Echo ISSN 2278-5264 প্রতিধ্বতি the Echo An Online Journal of Humanities & Social Science Published by: Dept. of Bengali Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam, India. Website: www.thecho.in Political Phenomena in Barak-Surma Valley during Medieval Period Dr. Sahabuddin Ahmed Associate Professor, Dept. of History, Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam Email: [email protected] Abstract After the fall of Srihattarajya in 12 th century CE, marked the beginning of the medieval history of Barak-Surma Valley. The political phenomena changed the entire infrastructure of the region. But the socio-cultural changes which occurred are not the result of the political phenomena, some extra forces might be alive that brought the region to undergo changes. By the advent of the Sufi saint Hazrat Shah Jalal, a qualitative change was brought in the region. This historical event caused the extension of the grip of Bengal Sultanate over the region. Owing to political phenomena, the upper valley and lower valley may differ during the period but the socio- economic and cultural history bear testimony to the fact that both the regions were inhabited by the same people with a common heritage. And thus when the British annexed the valley in two phases, the region found no difficulty in adjusting with the new situation. Keywords: Homogeneity, aryanisation, autonomy. The geographical area that forms the Barak- what Nihar Ranjan Roy prefers in his Surma valley, extends over a region now Bangalir Itihas (3rd edition, Vol.-I, 1980, divided between India and Bangladesh. The Calcutta). Indian portion of the region is now In addition to geographical location popularly known as Barak Valley, covering this appellation bears a historical the geographical area of the modern districts significance. -

Optimizing Uses of Gas for Industrial Development: a Study on Sylhet, Bangladesh by Md

Global Journal of Management and Business Research: A Administration and Management Volume 15 Issue 7 Version 1.0 Year 2015 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4588 & Print ISSN: 0975-5853 Optimizing Uses of Gas for Industrial Development: A Study on Sylhet, Bangladesh By Md. Asfaqur Rahman Pabna University of Science and Technology, Bangladesh Abstract- Proper and planned industrialization for any country can help to earn its expected GDP growth rate and minimize the unemployment rate. Industrial sector basically consists of manufacturing, together with utilities (gas, electricity, and water) and construction. But all these components to establish any industry are not available concurrently that only guarantee Sylhet. Here this study is conducted to identify the opportunities to generate the potential industrial sectors into Sylhet that ensures the proper utilization of idle money, cheap labor, abundant natural gas, and other infrastructural facilities. This industrialization process in Sylhet will not only release from the hasty expansion of industries into Dhaka, Chittagong but also focuses it to be an imminent economic hub of the country. As a pertinent step, this study analyzed the trend of gas utilization in different sectors and suggests the highest potential and capacity for utilizing gas after fulfilling the demand of gas all over the country. Though Sylhet has abundant natural resources and enormous potentials for developing gas-based industries, it has also some notable barriers which could easily be overcome if all things go in the same horizontal pattern. This paper concludes with suggestions that Sylhet could undertake the full advantage of different gas distribution and transmission companies and proposed Special Economic Zone (SEZ) as well for sustaining the momentum. -

Between Fear and Hope at the Bangladesh-Assam Border

Asian Journal of Social Science 45 (2017) 749–778 brill.com/ajss Between Fear and Hope at the Bangladesh-Assam Border Éva Rozália Hölzle Bielefeld University Abstract This paper is about the inhabitants of a small village in Bangladesh, which lies on the border with the Indian state of Assam. Due to an Indo-Bangladesh agreement, inhab- itants are confronted with losing their agricultural lands. In addition, since 2010, the Border Security Force of India (bsf) impedes residents in approaching their gardens, an action that has led to repeated confrontations between the bsf and the villagers. Both threats instigate high levels of fear among the residents. However, their hopes are also high. How can we explain equally high levels of fear and hope among the residents? I suggest that the simultaneous surfacing of fear and hope sheds light on “bipolar” state practices on the ground (i.e., at the same time targeting and protecting lives), as well as the entanglement of the existential and the political (i.e., vulnerability and a demand for recognition) in the everyday lives of the residents. Keywords fear – hope – violence – democracy – borderland – Bangladesh – Assam Introduction The village, Nolikhai, is located in the Greater Sylhet of Bangladesh on the border with Assam (see Figure 1). The majority of the residents are Pnar and War Khasis. They earn a subsistence income from betel leaf (pan) production. While their houses are in Bangladesh, their agricultural lands lie on a 300-acre- stretch of territory in no man’s land, that is, between Bangladesh and India. The villagers have not had official land titles over their area of residence or the farmlands since the colonial period. -

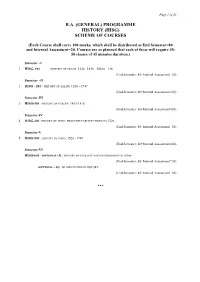

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

Sylhet Division

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Sylhet Division Includes ¨ Why Go? Sylhet ..............127 Pastoral Sylhet packs in more shades of green than you’ll Ratargul ............130 possibly find on a graphic designer’s shade card. Blessed Sunamganj .........131 with glistening rice paddies, the wetland marshes of Ratar- gul and Sunamganj, the forested nature reserves of Lowa- Srimangal & Around .............131 cherra, and Srimangal’s rolling hills blanketed in waist-high tea bushes, Sylhet boasts a mind-blowing array of land- scapes and sanctuaries that call out to nature lovers from around the world. Even while offering plenty of rural adventures for those Best Places willing to go the extra mile, Sylhet scores over several other to Sleep divisions in terms of its easy accessibility. Good transport links mean Sylhet’s famous tea estates, its smattering of Ad- ¨ Nishorgo Nirob Ecoresort ivasi mud-hut villages, its thick forests and its serene bayous (p136) are all just a few hours’ drive or train journey from Dhaka. ¨ Nazimgarh Garden Resort Given its relaxed grain, Sylhet is best enjoyed at leisure. (p127) Schedule a week at least for your trip here, especially if you ¨ Grand Sultan Tea Resort love outdoor activities. (p137) When to Go Best Places to Eat Sylhet Rainfall inches/mm ¨ Panshi Restaurant (p129) °C/°F Te mp 40/104 ¨ Woondaal (p129) 24/600 30/86 ¨ Kutum Bari (p137) 16/400 20/68 8/200 10/50 0/32 0 J FDM A M J J A S O N Mar–Nov Oct–Mar Dry Mar–May If Tea-picking season; time for Dhaka is too hot, season. -

RRP: Natural Gas Access Improvement Project (Bangladesh)

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Project Number: 38164 February 2010 Proposed Loans People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Natural Gas Access Improvement Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 15 January 2010) Currency Unit – Taka (Tk) Tk1.00 = $0.0145 $1.00 = Tk68.03 In this report, a rate of $1 = Tk70.00 is used. ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ADF – Asian Development Fund BERC – Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission BGFCL – Bangladesh Gas Fields Company Limited BGSL – Bakhrabad Gas Systems Limited CNG – compressed natural gas DPP – development project pro forma DSR – debt service ratio EIRR – economic internal rate of return EMRD – Energy and Mineral Resources Division FIRR – financial internal rate of return FNPV – financial net present value GSRR – gas sector reform road map GTCL – Gas Transmission Company Limited GTDP – Gas Transmission and Development Project ICB – international competitive bidding IEE – initial environmental examination IMRS – interface metering and regulating station IOC – international oil company JICA – Japan International Cooperation Agency LIBOR – London interbank offered rate OCR – ordinary capital resources Petrobangla – Bangladesh Oil, Gas, and Mineral Corporation QCBS – quality- and cost-based selection ROR – rate of return SCADA – supervisory control and data acquisition SGC – state-owned gas company SGCL – Sundarban Gas Company Limited TA – technical assistance TGTDCL – Titas Gas Transmission and Distribution Company Limited USAID – United States Agency for International Development WACC – weighted average cost of capital WEIGHTS AND MEASURES BCF – billion cubic feet ha – hectare km – kilometer m3 – cubic meter MMCFD – million cubic feet per day MW – megawatt TCF – trillion cubic feet NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the government and the Bangladesh Oil, Gas, and Mineral Corporation group of companies ends on 30 June. -

Women Education in Colonial Assam As Reflected in Contemporary Archival and Literary Records Chiranjib Dahal

SSRG International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Volume 8 Issue 3, 80-86, May-June, 2021 ISSN: 2394 – 2703 /doi:10.14445/23942703/IJHSS-V8I3P112 © 2021 Seventh Sense Research Group® Women Education in Colonial Assam as Reflected In Contemporary Archival And Literary Records Chiranjib Dahal Assistant Professor, Department of History, J.D.S.G. College, Bokakhat Dist.: Golaghat, State: Assam, Country: India 785612 Received Date: 15 May 2021 Revised Date: 21 June 2021 Accepted Date: 03 July 2021 Abstract - The present paper makes an attempt to trace the which can be inferred from literacy rate from 0.2 % in genesis and development of women’s education in colonial 1882 to 6% only in 1947(Kochhar,2009:225). It reveals Assam and its contribution to their changing status and that for centuries higher education for women has been aspirations. The contribution of the native elites in the neglected and the report University Education Commission process of the development of women education; and 1948 exposed that they were against women education. In social perception towards women education as reflected in their recommendation they wrote “women’s present the contemporary periodicals are some other areas of this education is entirely irrelevant to the life they have to lead. study. Educational development in Assam during the It is not only a waste but often a definite disability” colonial rule has generally been viewed by educational (University Education Commission Report, Government of historians to be the work of British rulers who introduced India, 1948-49). Educational development in Assam a system of education with the hidden agenda of initiating during the colonial rule has generally been viewed by a process of socialization. -

Event, Memory and Lore: Anecdotal History of Partition in Assam

ISSN. 0972 - 8406 61 The NEHU Journal, Vol XII, No. 2, July - December 2014, pp. 61-76 Event, Memory and Lore: Anecdotal History of Partition in Assam BINAYAK DUTTA * Abstract Political history of Partition of India in 1947 is well-documented by historians. However, the grass root politics and and the ‘victim- hood’ of a number of communities affected by the Partition are still not fully explored. The scholarly moves to write alternative History based on individual memory and family experience, aided by the technological revolution have opened up multiple narratives of the partition of Assam and its aftermath. Here in northeast India the Partition is not just a History, but a lived story, which registers its presence in contemporary politics through songs, poems, rhymes and anecdotes related to transfer of power in Assam. These have remained hidden from mainstream partition scholarship. This paper seeks to attempt an anecdotal history of the partition in Assam and the Sylhet Referendum, which was a part of this Partition process . Keywords : sylhet, partition, referendum, muslim league, congress. Introduction HVSLWHWKHSDVVDJHRIPRUHWKDQVL[W\¿YH\HDUVVLQFHWKHSDUWLWLRQ of India, the politics that Partition generated continues to be Dalive in Assam even today. Although the partition continues to be relevant to Assam to this day, it remains a marginally researched area within India’s Partition historiography. In recent years there have been some attempts to engage with it 1, but the study of the Sylhet Referendum, the event around which partition in Assam was constructed, has primarily been treated from the perspective of political history and refugee studies. 2 ,W LV WLPH +LVWRU\ ZULWLQJ PRYHG EH\RQG WKH FRQ¿QHV RI political history. -

Power Structure, Discipline, and Labour in Assam Tea Plantations Under Colonial Rule

IRSH 51 (2006), Supplement, pp. 143–172 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859006002641 # 2006 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Power Structure, Discipline, and Labour in Assam Tea Plantations under Colonial Rule Rana P. Behal The tea industry, from the 1840s onwards the earliest commercial enterprise established by private British capital in the Assam Valley, had been the major employer of wage labour there during colonial rule. It grew spectacularly during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when tea production increased from 6,000,000 lb in 1872 to 75,000,000 lb in 1900 and the area under tea cultivation expanded from 27,000 acres to 204,000 acres.1 Employment of labour in the Assam Valley tea plantations increased from 107,847 in 1885 to 247,760 in 1900,2 and the industry continued to grow during the first half of the twentieth century. At the end of colonial rule the Assam Valley tea plantations employed nearly half a million labourers out of a labour population of more than three-quarters of a million, and more than 300,000 acres were under tea cultivation out of a total area of a million acres controlled by the tea companies.3 This impressive expansion and the growth of the Assam Valley tea industry took place within the monopolistic control of British capital in Assam. An analysis of the list of companies shows that in 1942 84 per cent of tea estates with 89 per cent of the acreage in the Assam Valley were controlled by the European managing agency houses.4 Throughout India, thirteen leading agency houses of Calcutta controlled over 75 per cent of total tea production in 1939.5 Elsewhere I have shown that the tea companies reaped profits over a long time despite fluctuating international prices and slumps.6 One of the most notable features of the Assam Valley tea plantations was that, unlike in the cases of most of the other major industries such as jute, textiles, and mining in British India, it never suffered from a complete 1. -

Imperialism, Geology and Petroleum: History of Oil in Colonial Assam

SPECIAL ARTICLE Imperialism, Geology and Petroleum: History of Oil in Colonial Assam Arupjyoti Saikia In the last quarter of the 19th century, Assam’s oilfields Assam has not escaped the fate of the newly opened regions of having its mineral resources spoken of in the most extravagant and unfounded became part of the larger global petroleum economy manner with the exception of coal. and thus played a key role in the British imperial – H B Medlicott, Geological Survey of India economy. After decolonisation, the oilfields not only he discovery of petroleum in British North East India (NE) turned out to be the subject of intense competition in a began with the onset of amateur geological exploration of regional economy, they also came to be identified with Tthe region since the 1820s. Like tea plantations, explora tion of petroleum also attracted international capital. Since the the rights of the community, threatening the federal last quarter of the 19th century, with the arrival of global techno structure and India’s development paradigm. This paper logy, the region’s petroleum fields became part of a larger global is an attempt to locate the history of Assam’s oil in the petroleum economy, and, gradually, commercial exploration of large imperial, global and national political economy. petroleum became a reality. It was a time when geologists had not yet succeeded in shaping an understanding of the science of It re-examines the science and polity of petroleum oil and its commercial possibilities. Over the next century, the exploration in colonial Assam. Assam oilfields played a key role in the British imperial economy.